Richard Nixon: Life Before the Presidency

While courting common voters, Nixon made the most of his common origins; biographers, both sympathetic and critical, have tended to follow suit. He was born in one small California town (Yorba Linda) and grew up in another (East Whittier). His parents were in some ways opposites—Frank Nixon was as argumentative as Hannah Nixon was sweet-tempered. Richard Nixon suffered two great personal losses as a young man: the deaths of his younger brother Arthur after a short illness and his older brother Harold after a long one.

His school life brought a string of successes in endeavors common to politicians in training. He won debates and elections and leading roles in school dramatic productions. His grades were excellent, at both Whittier College and Duke University's law school. His scholastic achievements were not enough, however, to get him the jobs he applied for with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and with several prestigious law firms.

Nixon ended up in California, joining a Whittier law firm, the Whittier College board of trustees, and the Whittier Community Players. He fell romantically for a fellow cast member, Thelma Catherine "Pat" Ryan; they wed in 1940. Opportunities for work led Nixon back east, as a law professor's recommendation got Nixon a job with the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C. Following Pearl Harbor, Nixon enlisted in the Navy. His naval career ended with the war and in 1945 he was looking for his next job just as a group of prominent Southern California Republicans were looking for a suitable congressional candidate.

The Denigrative Method

As a campaigner, Nixon mastered early what historian Garry Wills called "The Denigrative Method" and what later analysts called "negative campaigning." Simply put, he attacked his opponents—sometimes unscrupulously, always effectively. His first campaign set the pattern.

His opponent was Jerry Voorhis, a New Dealer elected five times by voters of California's 12th congressional district. Voorhis was an anticommunist and refused to accept the endorsement of any political action committee unless the PAC renounced any and all communist influence. That stance deprived him of backing from the Congress of Industrial Organizations' PAC—CIO PAC—a communist-infiltrated labor group. When a newspaper falsely accused Voorhis of having the CIO PAC's endorsement, the congressman took out an ad proclaiming that the CIO PAC had refused to endorse him on account of his opposition to communists in the labor movement. "I can not accept the support of anyone who does not oppose them as I do," Voorhis said.

Nixon's campaign manager, however, claimed to have proof that Voorhis had the PAC's endorsement. During a debate with Nixon, Voorhis asked to see the proof. Nixon dramatically stepped forward with a bulletin of the local branch of the National Citizens Political Action Committee that included Voorhis among its recommendations. Voorhis pointed out that Nixon's evidence was about the NCPAC, not the CIO PAC, but the damage was done. Nixon had successfully linked Voorhis in the minds of voters to "the PAC," a tactic that helped him defeat Voorhis in November.

The House GOP rewarded Nixon with a seat on the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he rose to national stardom during the investigation of Alger Hiss. Through the presentation of evidence before HUAC and at two trials, Hiss, a prominent employee in the U.S. State Department, was revealed to have passed information to the Soviets. Proof of this espionage has only grown more overwhelming in recent years with the declassification of the "Venona" intercepts, decrypted Soviet cables on communist activities in America. Nixon won reelection in 1948 with the endorsement of both parties.

In 1950, his reputation buoyed by the Hiss case, Nixon ran for the Senate against Helen Gahagan Douglas in a campaign that echoed his race with Voorhis. This time, the Nixon campaign manual included a "pink sheet" comparing his opponent's voting record to that of Communist Party-liner Vito Marcantonio—what Nixon referred to as the "Douglas-Marcantonio axis." Nixon won a seat in the Senate and an indelible sobriquet—"Tricky Dick."The next rung up the ladder was the most important. In 1952, Dwight David Eisenhower, war hero and political phenomenon, gave Nixon the vice presidential nomination on the Republican ticket after the junior senator did some pre-convention maneuvering to lure California delegates into the Ike column. Then scandal struck, but not very hard. "SECRET RICH MEN'S TRUST FUND KEEPS NIXON IN STYLE FAR BEYOND HIS SALARY," screamed the New York Post. Nixon linked his troubles to the Reds. "You folks know the work that I did investigating Communists in the United States," he said at his next campaign stop. "When I received the nomination for the vice presidency I was warned that if I continued to attack the Communists in this government they would continue to smear me." Actually, the story came not from Communists but from Republicans—specifically, some disgruntled California politicos who thought Nixon should have been more steadfastly behind the favorite son presidential candidacy of Governor Earl Warren.

Nixon's fund may have been unseemly—it was actually used to keep him on the campaign trail, not living "in style"—but it was not illegal. The candidate defended it in a nationally televised address whose emotional high point—a promise made to his little daughter Tricia never to return one campaign gift, a cocker spaniel puppy named Checkers—made it forever known as the "Checkers Speech." Public response to the speech was overwhelmingly positive. A political star was reborn. Ike and Dick won the 1952 election in a landslide.

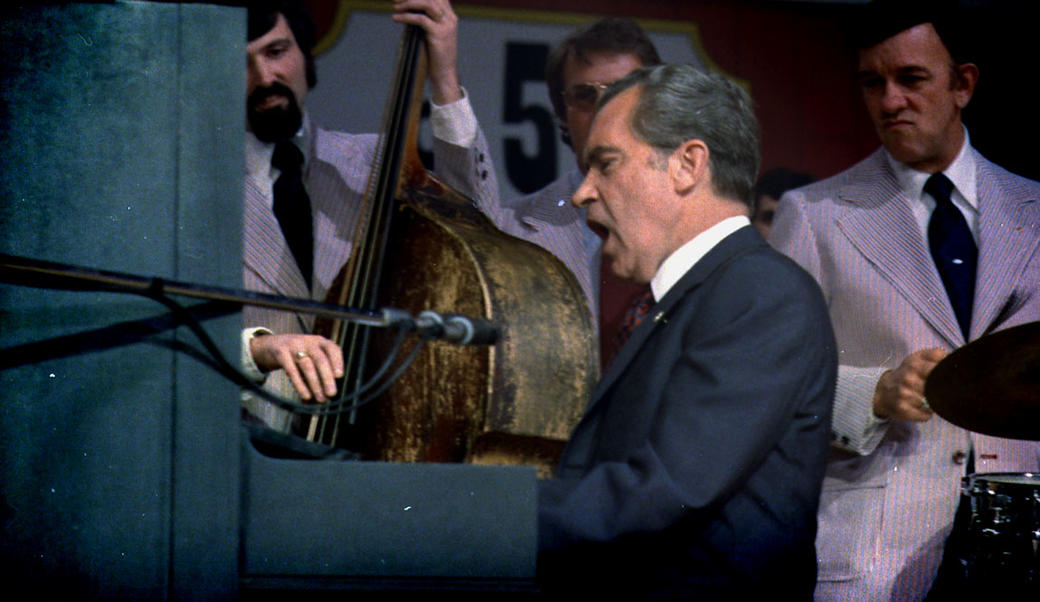

As vice president, Nixon burnished his reputation for foreign policy expertise with international travel to dozens of countries. His South American tour garnered international headlines when a mob in Caracas, Venezuela, stoned his motorcade. The confrontations with the demonstrators abroad only made him more popular at home. His 1959 trip to the Soviet Union was even more dramatic and politically helpful. While taking in an exhibit showcasing a General Electric model kitchen at the U.S. Trade and Cultural Fair in Sokolniki Park, Nixon and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev traded words about the merits of their respective countries. Their exchange became known as the "kitchen debate":Nixon: There are some instances where you may be ahead of us, for example in the development of the thrust of your rockets for the investigation of outer space; there may be some instances in which we are ahead of you—in color television, for instance.

Khrushchev: No, we are up with you on this, too. We have bested you in one technique and also in the other.

Nixon: You see, you never concede anything.

Khrushchev: I do not give up.

Nixon: Wait till you see the picture. Let's have far more communication and exchange in this very area that we speak of. We should hear you more on our televisions. You should hear us more on yours.

Khrushchev: That's a good idea. Let's do it like this. You appear before our people. We will appear before your people. People will see and appreciate this.

Earlier, when President Eisenhower suffered a heart attack, Nixon's calm, understated performance as temporary steward of the nation's business won him glowing reviews in the news media. But the President's medical problem gave Democrats the opening to claim that a vote to re-elect Eisenhower in 1956 might be, in effect, a vote for Nixon to become President. Ike's popularity with Republicans, Democrats, and Independents, however, made it difficult for the opposition party to take him on directly. Nixon, the partisan politician, made a much more tempting political target. In the end, such arguments had little effect on the voters, who re-elected Eisenhower and Nixon in a second landslide.

The Election of 1960

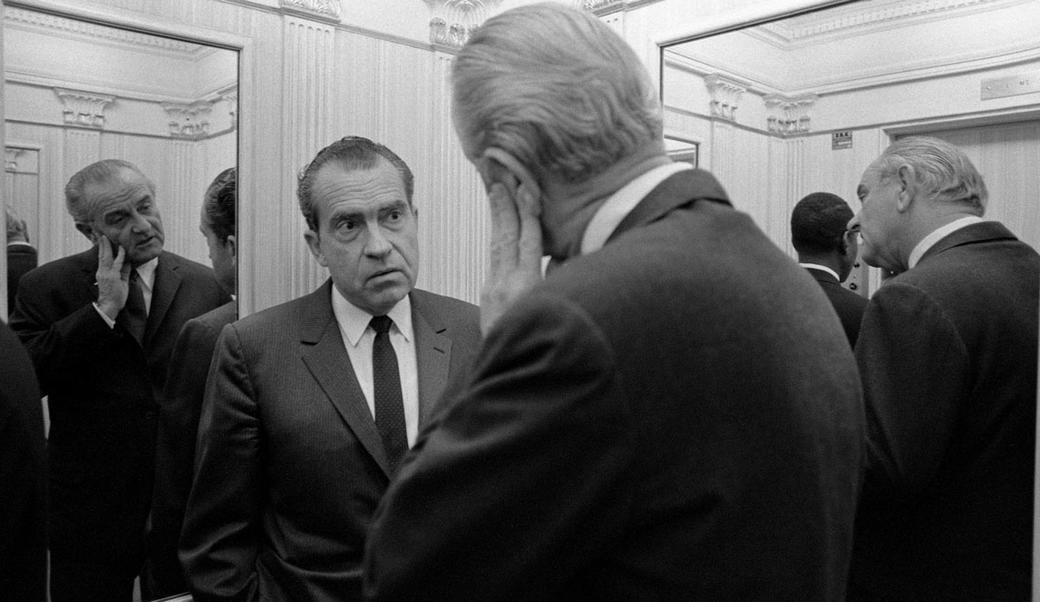

The presidential election of 1960 is best remembered for the first televised debate between Nixon and the Democratic nominee, John F. Kennedy. For many observers, the contrast between the pale, sweaty Nixon and the bronze, poised Kennedy captures the importance of image in politics, though the vote totals for the candidates—it was the closest election of the twentieth century—indicates that image is far from everything. (See Kennedy biography, "Campaign and Election" section for details.)Nixon blamed his defeat on other factors. An economic recession had bottomed-out shortly before Election Day. Also, Kennedy had the advantage of the challenger, the ability to stay on the offensive, while Nixon had to defend the record of the Eisenhower administration. And, fatefully, Nixon convinced himself that he was the victim of the Kennedys' ruthlessness:"We were faced in 1960 by an organization that had equal dedication to ours and unlimited money, that was led by the most ruthless group of political operatives ever mobilized for a presidential campaign. Kennedy's organization approached campaign dirty tricks with a roguish relish and carried them off with an insouciance that captivated many politicians overcame the critical faculties of many reporters. . . . From this point on I had the wisdom and wariness of someone who had been burned by the power of the Kennedys and their money and by the license they were given by the media. I vowed that I would never again enter an election at a disadvantage by being vulnerable to them—or anyone—on the level of political tactics."For Garry Wills, this passage from Nixon's memoirs suggests the inevitability of Watergate.

Nixon spent much of 1961 writing a book, Six Crises, and contemplating his return to politics. In 1962, he ran for governor of California and lost big. After his last defeat, he held what he claimed was his "last press conference," angrily telling reporters, "You won't have Dick Nixon to kick around any more."