George Washington: Foreign Affairs

Washington’s foreign policy focused on protecting the independence of the new nation and avoiding expensive and deadly wars. During Washington’s first term, European powers sought every opportunity to undermine American sovereignty. British forces provided ammunition and funds for Native American nations to attack western towns. Spanish imperial forces denied critical trade access to the Mississippi River, and settlements in Florida welcomed enslaved people who escaped from the southern colonies.

The French Revolution

While those challenges tested Washington’s patience, they were nothing compared to the threat posed by the French Revolution and the subsequent war between France and Great Britain. In 1789, King Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General (the French version of the legislature). Over the next few years, the assembly passed constitutional reforms before forming the French Republic in September 1792.

Initially, Americans cheered the French Revolution as the natural successor to the American version, especially since many revolutionaries, such as the Marquis de Lafayette, had played important roles in both revolutions. However, the French Revolution devolved into anarchy and violence, culminating in the execution of the king and queen in 1793. Following the royal executions, a more radical regime assumed power under the leadership of Maximilien Robespierre, known as the Reign of Terror for its regular executions of suspected spies and traitors. By July 1794, when Robespierre was deposed, at least 16,000 people had been executed, most by the infamous guillotine.

The violence of the French Revolution horrified many Americans. Federalists, like Washington and Hamilton, distrusted the radicalism of the French Revolution and feared the anarchy would spread to North American shores. Democratic-Republicans, like Jefferson, opposed the violence but remained more loyal to the French. Both sides demonstrated their preferences through clothing—the Federalists wore black cockades on their hats or pinned to their dresses, while the Democratic-Republicans adopted the blue, red, and white cockade.

These conflicting loyalties clashed in February 1793, when the Revolutionary regime in France declared war on Great Britain. Soon the conflict threatened to engulf the United States. With the war looming, Washington convened his cabinet in April 1793 and asked for the secretaries’ advice on how to remain neutral. The secretaries unanimously agreed the nation must avoid war but disagreed on how best to enforce that neutrality. Hamilton advocated for a strict neutrality, which would favor the British, while Jefferson preferred a looser neutrality, which would benefit the French.

The arrival of the new French minister to the United States complicated their attempts to keep the nation, and its citizens, out of the conflict. The French minister, Citizen Edmond Charles Genêt, arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1793 and disregarded Washington’s proclamation of neutrality. He traveled to Philadelphia and used its port to arm and outfit a fleet of French privateers, which were private ships sailing and attacking British ships under a French license. Genêt also ignored Jefferson’s repeated warnings to cease his activities. In August 1793, Washington and the cabinet requested Genêt’s recall from France—the first time the United States had requested the recall of a foreign minister.

In April 1793, Washington and the cabinet also crafted a series of rules of neutrality, which prohibited the arming of privateers and naval ships of belligerent nations and permitted the commerce of private vessels not intended for warfare. When Congress convened later that fall, they codified those rules into law, which governed periods of neutrality until the Civil War. By accepting the neutrality rules, Congress essentially approved of Washington’s handling of the crisis and ceded authority over foreign policy to the executive branch.

Relations with Britain

While Washington and the cabinet were fighting to keep relations with France neutral, tensions with Britain accelerated. The Anglo-American relationship had never fully recovered after the end of the Revolution, and three sticking points threatened to devolve into a new conflict. First, once the colonies left the British empire, they lost trading privileges in British ports. American merchants insisted on free and neutral trade policy and demanded access to ports, especially in the Caribbean.

The second point of contention were the unfulfilled terms of the Treaty of Paris (1783). The treaty dictated that the British would turn over military forts in the Ohio Valley and pay restitution to southern slave owners for the enslaved individuals who had escaped on British ships. Americans would repay their prewar debts they owed to British merchants. Yet by 1794, the forts remained in British hands, southern slave owners remained uncompensated, and British merchant debts remained unpaid. From their base in the western forts, British officials provided aid and munitions to Native American nations to attack US borders.

The third point of contention was the British seizure of ships sailing back and forth between the United States and France. Americans insisted the ships were neutral, whereas the British insisted the ships were carrying war materials and aiding the French in their ongoing war.

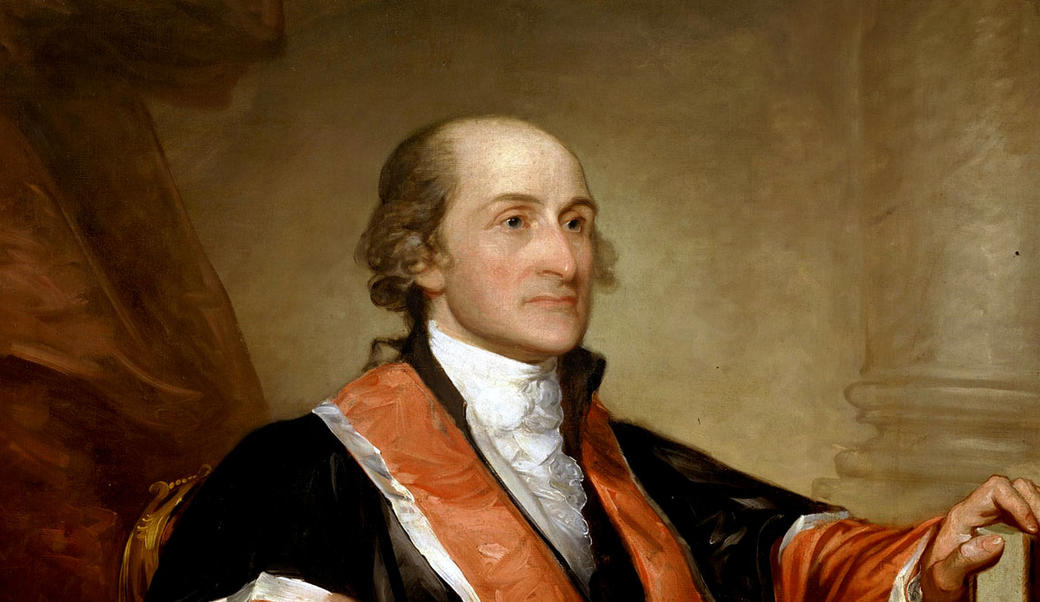

In 1794, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London to negotiate a diplomatic solution. Jay signed a new treaty on November 19, 1794 and sent it back to the United States for ratification. In June 1795, the Senate ratified the treaty in an emergency session, and Washington applied his signature in August. The treaty created commissions to adjudicate prewar debts owed to British merchants, opened British ports to limited American trade, and required British forces to withdraw from western forts on American territory.

Jay had entered the negotiations with almost zero leverage, so the concessions he extracted from the British were remarkable. But many southerners believed their interests had not been as well represented as those of northerners. Additionally, many Democratic-Republicans believed that the treaty violated the spirit of neutrality and the Franco-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1778). After months of contentious debates, in May 1796, the House of Representatives finally agreed to raise the funds to fulfill American obligations.

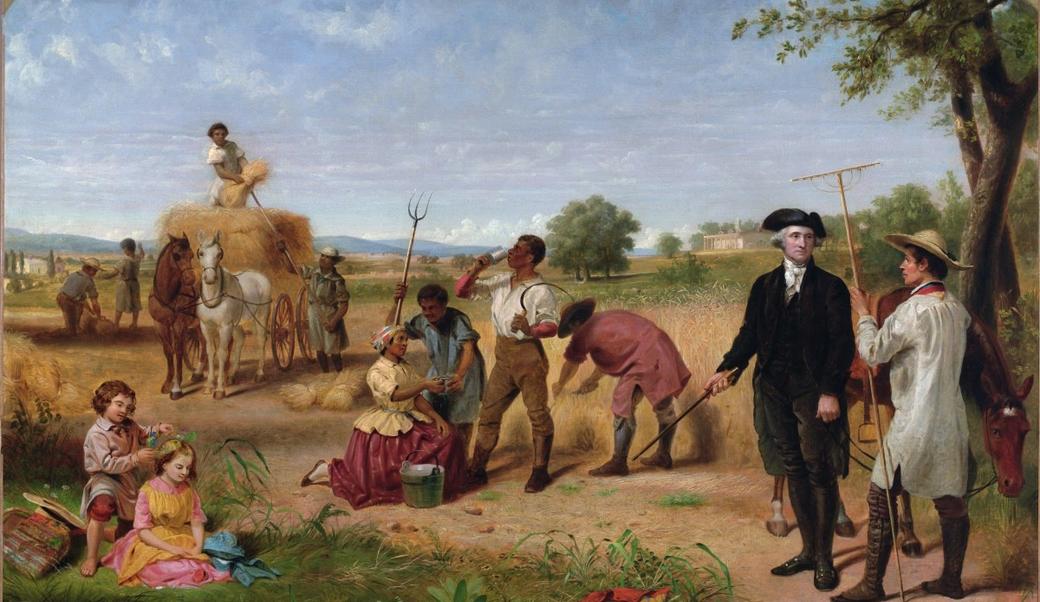

Simultaneously, Thomas Pinckney negotiated another, much more popular treaty with Spain. The resulting agreement, known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or Pinckney’s Treaty, resolved territorial disputes between the United States and Spain, granted American ships the right to sail and trade on the Mississippi River, and gave Americans the right to deposit goods for sale in the port of New Orleans (which was under Spanish control). This treaty was especially popular with farmers out west who depended on the waterways to send their goods to market, rather than over the mountains, which was much more expensive and impassible during winter.