Mississippi Burning

Listen to the Secret White House Tapes when three civil rights activists disappeared

In the summer of 1964, the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) coordinated efforts to register African American voters in Mississippi as part of its three-year-old civil rights organization efforts. Beginning in June, the first contingent of Freedom Summer volunteers began arriving in Mississippi after training sessions in Oxford, Ohio. Approximately 250 activists made it to the Magnolia State between June 20 and June 22. One of them was Andrew Goodman, the son of a prominent Jewish family from Manhattan.

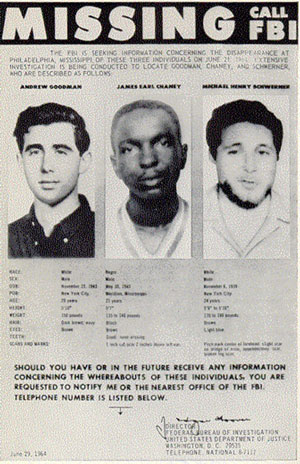

On June 21, 1964, two days after the Senate passage of the Civil Rights Act and two weeks before President Johnson signed that landmark piece of legislation, Andrew Goodman went with James Chaney and Michael Schwerner to investigate the burning of the Mt. Zion Church in the Longdale community in Neshoba County, near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Chaney and Schwerner were both veteran civil rights activists involved in political mobilization efforts, one an African American from Mississippi and the other a Jewish social worker from New York City whom some locals called "Goatee." While attempting to return to Meridian, Mississippi, the three men were arrested for traffic violations and jailed. After being released from jail at 10 p.m., they disappeared.

When they did not report in by phone as civil rights workers in Mississippi were trained to do, fellow activists began calling local and federal law-enforcement officials. Although many feared the worst, none of them knew for certain that a band of white supremacists associated with the Ku Klux Klan and the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Department had murdered them on a rural roadway.

Secret White House Tapes

Despite the existence of court records, news reports, oral histories, and documents relating to the investigation, the violent events of that summer will never be entirely clear, and students of history will continue to debate the ambiguities of evidence in attempting to understand that muggy, 80-degree Mississippi night. One resource, though, that captures the immediacy of their disappearance and the complications it presented for federal and state authorities—and for activists—is the collection of secret recordings made by President Lyndon Johnson.

President Johnson ramped up the investigation into the disappearances by prodding FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, by seeking advice from Cabinet officers and congressional leaders, and by involving the Defense Department (eventually bringing in hundreds of sailors to scour the countryside, particularly its swampy areas where it was presumed the bodies might have been hidden). The president received reports and held meetings throughout the day. Beginning around noon, he turned on his Dictabelt telephone recorders.

"Fill-up Mississippi with FBI men"

President Johnson’s first recorded report was with Lee White, a holdover from the Kennedy administration who served as Johnson’s chief aide on civil rights matters. The two discussed how best to respond to James Farmer, the director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which was one of the chief groups involved in the COFO voter registration campaign and Freedom Summer.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 12:35 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Lee White

Tape: WH6406.13

Conversation: 3818

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"What do you think happened to them?"

Over the next four hours, the president spoke to the Speaker of the House (twice) and the secretary of commerce—Southerner Luther Hodges—about the complications of using extensive federal force in the South. He also made several calls regarding campaign issues and received a message from Attorney General Robert Kennedy. At 3:35 p.m., Johnson tried to return Kennedy’s call, but he spoke instead to Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. This snippet is part of a nine-minute call.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 3:35 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Nicholas Katzenbach

Tape: WH6406.13

Conversation: 3832

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"It's a publicity stunt"

Just before 4 p.m., the president made contact with arch-segregationist James Eastland, a colleague from Johnson’s Senate days who was a virulent opponent of the civil rights movement. In the call, Eastland, in his thick Mississippi Delta accent, mocked the idea that any violence had occurred and gave voice to a prevalent white Southern belief that the disappearance was a “publicity stunt."

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 3:59 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, James Eastland

Tape: WH6406.14

Conversation: 3836

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"We found the car"

Almost immediately after, the president received news from the longtime FBI director that seemed to confirm the worst possible outcome. The Bureau had found the burned car of the activists, and Hoover expressed his assumption that “these men have been killed.”

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 4:05 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover

Tape: WH6406.14

Conversation: 3837

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"I'm here with the parents of the missing boys"

While the parents were in the office, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara phoned twice. The second time, Johnson spoke specifically about Mississippi. The recording here begins with Johnson speaking to the families.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 5:44 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara

Tape:WH6406.14

Conversation: 3855

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"The bodies were not in the car"

The news about the car dominated discussions (along with calls from Senator Everett Dirksen about an Illinois navigation project) until Hoover called back at 7:15 p.m. with news that no bodies were found in the car. Prior to Hoover’s call, Robert Kennedy had arrived at the White House to help plan the Justice Department’s involvement in the investigation and to lobby former CIA Director Allen Dulles to become an “impartial observer” of the situation in Mississippi for the administration.

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 7:15 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, J. Edgar Hoover

Tape: WH6406.15

Conversation: 3869

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

Miss Schwerner

After hearing the news from Hoover, Johnson made personal calls to the parents of Schwerner and Goodman, but was unable to find the phone number for the family of Chaney. Johnson had received white parents’ numbers from their congressmen, but had to rely on AT&T operators for Chaney’s number (a misspelling of Chaney's name kept them from finding the number). Ten minutes before the call to Anne Schwerner, Johnson exchanged views with Mississippi Governor Paul Johnson, a successor to Ross Barnett and a man who in a previous campaign had referred to the NAACP as standing for “Niggers, Apes, Alligators, Coons, and Possums.”

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 8:35 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Anne Schwerner

Tape: WH6406.16

Conversation: 3882

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"None of them were burned"

Johnson continued his phone calling for another two hours, speaking with the father of Andrew Goodman, to members of Congress, to Lee White, Allen Dulles, and, finally, to Secretary of State Dean Rusk (about the resignation of Henry Cabot Lodge as ambassador to South Vietnam).

Date: June 23, 1964

Time: 8:50 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Robert Goodman

Tape: WH6406.16

Conversation: 3884

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

June 24 to August 3, 1964

Over the next week, Johnson continued to press for results in the investigation, while turning more of his attention to other matters of state, particularly the conference report on the Civil Rights bill. In a triumphal moment, he signed the act on July 2. The bill’s victory was bittersweet for activists in Mississippi and the loved ones of the three missing men. Despite exploring hundreds of leads, the investigation had yielded scant evidence of the men’s location and had led to no arrests. A major break in the case occurred in early August, when an FBI informant (paid $30,000) pointed the Bureau to a farm pond just southwest of Philadelphia.

"The FBI has found three bodies"

Assistant Director of the FBI Cartha “Deke” DeLoach called Johnson to notify him that the bodies had been found. That day, Johnson was also coping with racial disorders in New Jersey as well as the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Date: August 4, 1964

Time: 8:01 p.m.

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Cartha “Deke” DeLoach

Tape: WH6408.05

Conversation: 4693

Click to listen to the whole conversation.

"Call the families and tell them"

Immediately following the conversation with Cartha DeLoach, Johnson calls Lee White.

Date: August 04, 1964

Participants: Lyndon Johnson, Lee White

Tape: WH6408.05

Conversation: 4694

Violence in Mississippi

Before the Freedom Summer students left Ohio, they had been briefed by John Doar, a representative from the U.S. Justice Department who informed them that the federal government could not provide them with protection in Mississippi. He emphasized that local and state officials held the responsibility for maintaining law and order, an ominous assurance given Mississippi's track record for not protecting civil rights workers.

In Mississippi and elsewhere in the South, civil rights activists complained bitterly about the lack of federal protection, and many believed that Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover was an enemy of the movement (and he certainly had many activists under FBI surveillance). A prominent feeling was that the FBI investigated white racial violence when pressed to do so, but those investigations often went little beyond intelligence gathering and thus served little deterrent value to would-be white terrorists.

At the time, the disappearance and presumed murder of these activists at the beginning of Freedom Summer captivated the nation and became a landmark moment in the history of the civil rights movement. The attention focused on Mississippi, however, did not stop violence against civil rights activists or black Mississippians. Over the course of Freedom Summer, three other bodies of murdered black men were found, each of them had been lynched: Charles Moore and Henry Dee were found in mid-July in a lake off of the Mississippi River; a young man wearing a CORE t-shirt, likely a teenager named Herbert Oarsby, was found in the Big Black River. There were also approximately 70 bombings or burnings, 80 beatings, and more than 1,000 arrests of activists. The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) incident report, a single-spaced document that offered brief daily summaries, was more than 10 pages long.

The FBI's case into the disappearance of the civil rights workers became part of their investigation into church burnings known as MIBURN or Mississippi Burning. A controversial Hollywood film of the same name was released in 1988 (Mississippi Burning; directed by Alan Parker). It stirred further interest in the case, but caused many civil rights activists to shudder in horror at the heroic presentation of the FBI and at the downplaying of black activism in the movement.

Exactly 41 years later, the state of Mississippi obtained its first homicide conviction in the case. On Tuesday June 21, 2005, nine white and three black jurors convicted 80-year-old Edgar Ray “Preacher” Killen of manslaughter for his role in orchestrating the nighttime roadside lynching, which transpired approximately a half-mile from his house. For his crime, Killen received the maximum sentence of 60 years.

Although this was the first state conviction, it was not the first in the case, as federal conspiracy charges had led to prison time for a few of the other men involved in the murders. In October 1967, in federal court, an all-white jury convicted seven white men, including Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price. Eight others, including Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, were acquitted. The cases of three others—one of them involving Edgar Killen—ended in a mistrial. At the time, no one was brought to trial on state murder charges. Killen’s 2005 trial has proved once again the epigram of Mississippi’s sage novelist William Faulkner that "the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” While the U.S. government is engaged in a struggle against terrorism worldwide, the Killen case offers a reminder of the realities of racial segregation and the use of terrorism at home to attempt to preserve white supremacy.

Learn more about Lyndon B. Johnson or listen to our collection of tapes.