Transcript

Riley

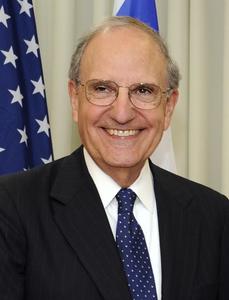

This is the George Mitchell interview as a part of the Clinton Presidential History Project. We usually repeat the fundamental ground rule at the beginning, which is that the interview is being conducted under a veil of strict confidentiality. None of us is allowed to repeat anything that is said here at the table to encourage you to speak candidly to the historical record. We discussed this at some length before we got on tape.

I want to begin by asking, do you recall when you first met President Clinton?

Mitchell

I don’t recall. I think it was shortly after he announced his candidacy for the Presidency that he came to my office in the Capitol—I was then the Senate majority leader—to tell me about his plans and introduce himself. I may have met him before that, but I don’t have any specific recollection.

Riley

This would have been toward the end of ’91.

Mitchell

I can’t remember the date, sometime in ’91.

Riley

Okay. Were you somebody who had any background with the DLC [Democratic Leadership Council] at that time?

Mitchell

No. I had been a member of the Democratic National Committee many years earlier, but had not been involved with the DLC. I had spoken at DLC meetings but was not a member. I think he came just because I was the majority leader. He probably saw the speaker and others on the same day.

Riley

Senator, had you given any thought to running yourself in 1992?

Mitchell

I had indeed. I had gotten a lot of suggestions and requests, mostly from my colleagues in the Senate, but also from a good number of fundraisers. I thought about it but decided not to do it, primarily because I had just become Senate majority leader a couple of years earlier. My consideration would have occurred early in ’91. I didn’t think much about it. I decided that it wasn’t feasible for me to both serve as majority leader and run. Having just become majority leader, I didn’t want to leave that. It was not a difficult decision. I didn’t give it a great deal of thought.

Riley

Did you have a preferred candidate going into ’92?

Mitchell

I did not.

Riley

Did you support anybody during the ’92 primary season?

Mitchell

No. My recollection is I didn’t get involved. For one thing, I can’t remember exactly how many, but several Senators were candidates, people who were part of the Democratic caucus in the Senate, of which I was the leader. So I thought it was prudent not to get involved at that point. I can’t remember who all—Bob Kerrey ran, Tom Harkin ran.

Martin

Paul Tsongas.

Mitchell

Paul Tsongas ran then.

Riley

Right.

Mitchell

Paul Simon had run in ’88, I think not ’92.

Riley

I think that’s correct. He was not in the mix really in ’92.

Mitchell

I knew most of the candidates, so I didn’t get involved.

Riley

Did Clinton do reasonably well in Maine? I’m trying to recall whether—I guess you would have known the people who were running his organization?

Mitchell

I can’t recall what happened in the caucuses. The Maine Democratic Party had a strong, what some would call a very liberal, activist wing. It was the best state for Jerry Brown. It was the best state for Jesse Jackson. Gary Hart did very well there when he ran against Fritz [Walter] Mondale. I don’t recall how Clinton did in the caucuses. I do recall him coming and speaking at an event prior to the caucuses, which I attended and spoke at. I think he made a very good impression.

Martin

I’m curious. You said you met him early when he first announced his campaign. Were there any particular recollections you have of this meeting?

Mitchell

No. It may have been before he formally announced. I’m not sure of the date, but it was in connection with his prospective, or by then actual, candidacy. It was a very cordial meeting. Almost everybody who announced and ran did the same thing, so it was one of several meetings. They were all cordial and friendly, not earthshakingly substantive.

Riley

Did you go to the convention that year?

Mitchell

I did. I’ve been to the convention every year since 1964.

Riley

Do you have any particular recollections of the ’92 convention?

Mitchell

He did a good job, obviously. I’d had a long experience of dealing with President [George H.W.] Bush. I was the Senate majority leader during his entire term of office, so had spent a good deal of time in consultation—sometimes in agreement, sometimes not—with the President and with his team. I had a fair amount of knowledge about their background and their campaign effort. I thought that Clinton made a good choice in Al Gore and it was a good, young, vibrant team. Like most of the people who attended the convention, and many Americans, I was impressed.

Riley

Did you play a part in the general election campaign then?

Mitchell

I was involved, actively helping to the extent I could, certainly in Maine. I can’t be sure of sequence in these things, as I’m sure you appreciate. I’ve made many, many appearances with President Clinton in Maine, but I can’t tell you which one was which campaign, and he came to Maine on my behalf when I sought—I’m trying to think of the timing of this now—after he was President he’d come up to Maine on my behalf. He’s been there many times since for other candidates. I’ve appeared with him a lot in Maine. I can’t recall precisely ’92, but I’m assuming that we did appear together at events.

Riley

As somebody from Arkansas, was he somebody who seemed to grasp whatever is peculiar about Maine, that makes it—

Mitchell

He has always been well informed and a quick study, knowledgeable about the place and the circumstances. As I later learned in dealing with him extensively when he was President and I was Senate majority leader, he was usually very well informed on the issues that we discussed, he and I individually and with groups of Senators, which is more often what occurred.

Riley

Getting beyond the general election, there’s an important period of transition there where you have a new Democrat coming in for the first time in a lot of years. There was a meeting that you went to in Little Rock—

Mitchell

Yes.

Riley

—fairly soon after the election. I wonder if you could tell us about that meeting, your memories of it.

Mitchell

Tom Foley, who was the speaker, and I—and I’m not sure, but it’s likely that Dick Gephardt was there as well, the majority leader, but I don’t recall precisely—went to Little Rock. We had a very good meeting, had dinner with the President-elect and Mrs. [Hillary Rodham] Clinton, and had a fairly lengthy chat. It was in part getting acquainted, getting to know each other. Everybody knew that we’d be working closely together over the next few years, and also partly talking about issues that were important to him, how we wanted to proceed and so forth.

What I can recall of it was that it was a very positive and productive meeting. I remember we had a press conference afterward where we talked about it. I think generally everybody had a good feeling about it.

Riley

There weren’t any alarm bells that went off?

Mitchell

I don’t recall any.

Martin

As majority leader, you want to hear certain signals from an incoming Democratic President?

Mitchell

Well, I’d never served as majority leader under a Democratic President before. This was a first experience for me. I was elected Senate majority leader in November 1988, just shortly after the general election in which President Bush was elected, so my previous four years had been with a Republican President.

I don’t know as I’d look for any signals. The obvious and expected desire to cooperate, to work together to advance common objectives, to do what we could to develop a program that was both good for the country, consistent with our party’s values and ideals, and had some prospect of being supported by Democrats and Republicans in the Senate.

Riley

Can you tell us what you were going through as you’re attempting to shift gears from being a minority party leader to a majority party leader at this time? There must be thousands of things that are different. How are you navigating through these waters in a fairly short period of time?

Mitchell

It was obviously very positive from our standpoint. I personally, and I think most of the Democratic Senators, had a very good relationship with President Bush during the first two years of his term. We worked together to enact a lot of very important pieces of legislation, one of which was the Clean Air Act, which was a major effort and had been made possible by President Bush. Prior to him, President [Ronald] Reagan had been adamantly opposed to any clean air legislation, and we couldn’t move a bill. But when Bush came in he said he favored it. The issue changed from whether there’d be a bill to what would be in the bill. We had a long negotiation. We passed it. We did a lot of other good things.

In the final two years of his term the relationship wasn’t as good. We’d had a highly contentious budget dispute in 1990. I won’t go into the details—that’s another Presidential—

Riley

We’ve heard a lot of details from the Bush people about that.

Mitchell

Relations generally went downhill. Of course they culminated in the famous breaking of his pledge, which they still blame on me and the Senate Democrats. For me personally, I can say it was just a great relief and a very hopeful and optimistic outlook to be working with a Democratic President who shared our views. We would no longer be confronted with opposing policies that we didn’t support or believe in and that we’d oppose, and thought we’d be now proceeding in a positive way.

Riley

Senator, there were some policies, though, that the candidate had voiced support for during the campaign that at least on some evidence they backed away from because of input that they got from Congress or individual members, one being campaign finance reform. I think general sort of reform, Congressional reform, with jobs and things of that nature. Did those kinds of things come up during the Little Rock meeting?

Mitchell

No, I don’t think they would have come up there. Let me address them if I can. The campaign finance reform issue peaked in President Bush’s term when we passed a pretty strong bill in the Senate and House, certainly the strongest bill that had been enacted between the 1974 major reform legislation and that time. It was tough because Democrats were not completely unified on it. A majority in the Senate strongly favored the legislation; a minority was less strongly in favor. In the House there was much more opposition among Democrats, who were pretty well entrenched and established, and they weren’t as interested in reform as the Senate was, but we got a pretty good bill through. President Bush vetoed it.

When President Clinton took office, the House Democratic position tended to prevail. They really were not—I exempt Speaker Foley and Dick Gephardt from this, because I think they really did want to move forward. But they were constrained by the views of a lot of their more senior members, who really were not as interested in pursuing it. Try as we might, we couldn’t get any people to gear up for it. There were other higher priorities that came along.

The other issue on which there was some difference was our China policy. President Clinton had vigorously criticized President Bush during the campaign for his policy. I shared that view, as did Nancy Pelosi, who was then a leading advocate of a tougher policy. Remember Tiananmen Square had occurred in ’89, if I’m not mistaken, the late ’80s. But once President Clinton took office and started getting a lot of advice, he clearly modified his position. I recall we went down for a few meetings and it was pretty obvious he was taking a more accommodating view.

Now the Bush people were very critical. You can understand their view. He had criticized Bush. In their view, he simply adopted Bush’s policy once he took office. If that is true, it wasn’t the first time in history and it won’t be the last, the so-called co-opting of other views. But there was a period of difficulty in trying to adjust to that. Nancy and I pretty much held our ground at the time, notwithstanding the President’s own views. Gradually over time, the issue changed. Tiananmen Square faded more into the background. You had different policies. China did, in fact, open up its economy. It has changed rather dramatically to this time. So that was one other area in which there was some tension. There were many, many others, of course.

The budget was a big issue when you get to that later on.

Martin

Can I ask—when the President is on one side with campaign finance, and the Senate and the House are having trouble with the issue, how does the President respond to you? Does he continue to push or does he back off immediately? How does that exchange work?

Mitchell

I can’t recall the details of it. But I don’t think he pushed real hard on campaign finance reform. I think the House guys made it pretty clear that they’d gone through a huge amount of difficulty when we passed the bill that President Bush had vetoed, and it didn’t become a major issue.

Riley

Do you have any recollections of the transitional period between the election and the inauguration when you’re trying to help introduce this new President into Washington? Do you have any specific recollections about how that process went?

Mitchell

No. Of course he campaigned all over the country and would have campaigned with every Democratic Senator. You say introduce him to Washington—I didn’t regard myself as any particular insider. I had not been in the Senate that long myself. I don’t recall any of that.

We did set up meetings with the Democratic Senators to try to get a sense of cohesion and support, but he met everybody on his own so he didn’t need me to introduce him to Democratic Senators or others in that category.

Martin

Did you have a sense of his political sense of the Senate?

Mitchell

I thought he had a pretty good sense of things. He obviously understood how the Senate worked. He had a good sense of issues. The same kind of quick study that I’d mentioned. Of course he had very close friends in Dale Bumpers and David Pryor, who were in the Senate at the time. He knew a number of other Senators, as I did. He knew them all, I’m sure, at some point. I thought that he was well informed and off to a good start. We ran into problems early on the gays in the military issue, but unfortunately I don’t think that it was well handled or certainly well characterized. I don’t think the President had wanted to make it a big issue. Some of the Republicans did, and so it got sort of front and center early in a way that was not beneficial. But it’s a learning process for everyone—even the most intelligent and best prepared.

Martin

One of the open questions that we’ve heard from folks is this question of Al Gore as an inroad to the Senate and whether that choice was political in terms of the age of Al Gore versus his intimate knowledge of the Senate in terms of how they get policy through. Do you have any sense of how Al Gore was used in this period?

Mitchell

I don’t think that President Clinton needed an envoy to the Senate. I’ve never discussed it with him, but I’d be very surprised if that was a major reason for picking Al Gore. I think he picked Al Gore because Al Gore is smart, an able public official, and would probably help him get elected and help him do a good job in office. As an envoy to the Senate I think that would be—I’m just guessing, but I’d assume that’s a minor consideration, if at all.

Riley

Were you picking up any signals during the transition period that the President was going to be in trouble on anything in particular? You mentioned the gays in the military and that sort—

Mitchell

No, there was a lot of anticipation about the budget, which of course is a major item. The recession of the previous year obviously had a negative effect on the Bush campaign, and there was a sizable deficit. That was back in the days when the Republicans were concerned about deficits—we all were—before the current regime. It was a huge issue.

Riley

We want to make sure that that history is recorded so that somebody will know that it actually existed.

Mitchell

It’s just incredible to me how they’ve gone from a period of intense concern about the deficit to one of complete disregard. But that’s another story. There was a lot of anticipation and I think discussion about the budget. I recall it would have been in the spring, I guess, of ’93, when the administration was in the process of developing the budget. We had a series of meetings at the White House, groups of Senators, about specific items in the budget, taxes, Social Security, things like that. I don’t recall any discussion during the transition about gays in the military or things that actually did erupt a little later on.

I think the most concern was about the economic situation of the country, the need for economic growth, job creation, the development—enactment—of a budget that would spur that growth and that job creation. If my memory is right, that’s pretty much what people were most concerned about.

Riley

Okay. In the Senate you would have spent a lot of your early days in the administration dealing with appointments, also confirmation—was it your sense at the time that the incoming administration that you were seeing being put together was one that you were supportive of, or were there any alarm bells or any problems that you had?

Mitchell

There were no alarm bells. You had the usual missteps. There was a brief, intense, flurry of attention to Zoë Baird, and those are the kinds of things that happen in every administration. You had some errors in judgment. I can’t recall, but there were maybe half a dozen—some Senator would get his nose out of joint at some nominee and there would be a couple of days of press focus. But I don’t recall any major problems.

Martin

Can you talk a little bit about—my guess is in your position as majority leader you would be in communication with most of the Democratic Senators on a regular basis.

Mitchell

Yes.

Martin

Were there any Senators or groups of Senators that had concerns about Clinton that they would communicate to you in terms of his policy program or his competence in terms of leadership or—

Mitchell

Sure. When we got into the budget there was all kinds of disagreement. The carbon tax was a huge item with a lot of Senators. You could get disagreement on every policy issue, but that’s par for the course, nothing unusual about that. I don’t think there was any negative feeling for the President. I think people thought it was terrific that he got elected and were to some extent surprised and gratified. The prospect of now working with a Democratic President and a Democratic Congress I think was viewed generally, in a highly positive sense by most of the Senators. That doesn’t mean they surrendered their own views or that they agreed on everything; they certainly didn’t. As I said, there was a huge amount of disagreement, and I suppose we’ll get to that in a moment. I think all-in-all it was pretty positive.

Riley

Did you have the same feeling about the White House staff? I’d asked the question about the administration, generally, about confirmation issues. But more generally, can you tell us about your early assessment of the White House staff itself?

Mitchell

I dealt with them all, so I can’t remember who the staff was at the beginning.

Riley

Mack McLarty would have been the first Chief of Staff.

Mitchell

Mack was a fine guy, good guy, had a good relationship with him, worked well with him, not a problem.

Riley

The Congressional affairs people?

Mitchell

Who would that have been?

Riley

Originally it would have been Howard Paster.

Mitchell

I’d known Howard for a long time.

Martin

Steve Ricchetti?

Mitchell

Steve too, yes, both very fine guys. It’s a tough job. I recall later—I don’t even know if Howard and Steve were there when Richard Shelby switched parties. The White House always has a strong desire for being tough, looking tough, and rewarding friends and punishing enemies. But the reality of the Senate is you can’t punish anybody. It’s counter-productive, in fact. Shelby later remarked how cordial I was to him, and I was. There’s nothing I could do to him that would have any effect on him, and the best you can do is try to be persuasive and make the best case you can and accept the results.

I think some of the guys in the White House understandably get frustrated when these Senators or some Congressmen appear to defy the White House or take different points of view and make public issues out of it. But that’s the reality of an independently elected legislative branch.

Riley

And a part of your job as majority leader is to help educate a White House to this reality?

Mitchell

Well, both sides. It’s to try to mediate, to try to minimize disputes, to try to resolve them, try to be a go-between and work it out on both sides. That’s part of the process.

Riley

One of the things that we have heard from some of the Congressional affairs people in the Clinton White House was that they were sort of surprised at the inability of President Clinton to make any inroads with the Republicans, starting very early on. I wonder if you could tell us about your own views on this. Did you feel like there was a missed opportunity in any way early in the administration for them to make common cause with some of the Republicans on an individual basis or to win the support of some of the moderates? Could you help us understand why the Republicans were so resistant, if they were, to this President?

Mitchell

I think first, most of them, probably all of them, would have been upset that he was elected.

Riley

Sure.

Mitchell

I think they’d become accustomed to Republican Presidents and didn’t have a high regard for Clinton, probably believed some of the rhetoric in the campaign about him. I think some of their Congressional leaders openly said that part of their job was to make sure he was a one-term President, so they weren’t going to be particularly cooperative. I think some of them were still upset about President Bush’s breaking of his tax pledge. When he did that he sort of blamed it on the Democrats in the Senate:

We had to do that to get the budget cuts.

It wasn’t the case in my view, but none the less understandable, part of the political process.Secondly, I think President Clinton went way out of his way to be accommodating to Republicans. I can recall him at leadership meetings being very courteous, very attentive, even when they said critical things—in fact, probably more so than he really had to be or should have been. Some of them were very direct in their comments and criticisms. This occurred over, for me, a two-year period, so I can’t particularly date things, but I can recall several times where members of the Republican leadership would make pretty direct and blunt statements to him that were critical, and he never engaged in any confrontational way. He tried to be accommodating and so forth.

Whether or not he might have wooed individuals outside of that context, I can’t judge. I don’t know who he talked to, who he saw, who he had dinner with, or anything like that. Whether that was a missed opportunity, I don’t know.

Riley

Right.

Mitchell

But at least in terms of the experience and the exposure I had, if there was a lack of communication, I can’t see how all or even much of the blame could be laid at his doorstep.

Riley

Is it your sense from that period that the Republicans were being unnecessarily difficult with this President?

Mitchell

I’m not sure how you define unnecessarily difficult. We had gotten along very well with President Bush in the first two years.

Riley

Right, and I was harkening back to that when I phrased the question, because you’re a minority leader who, at that period, clearly was working with the administration. I’m trying to use that as sort of a baseline. That doesn’t appear to be the case in your two years as majority leader.

Mitchell

Remember two things. First, when Bush came in, I was the majority leader. Democrats controlled the Senate.

Riley

But you were the opposition party.

Mitchell

We were the opposition. But the Republicans were in the minority when Clinton took over. I’m not sure; I think it may have been just circumstance. I recall very clearly in President Bush’s inaugural, he said,

I hold out my hand in friendship,

or something like that. I said we should take that; we should work with him as best we can. But by the end of it, relations were not good, and that’s what may have carried over to the Republicans. In other words, they may have taken the view that they’re going to treat Clinton the same way that they thought we treated Bush, which was actually not accurate in terms of the beginning of the Bush term. It was not as partisan an atmosphere as now exists, but it was difficult.Bob Dole is a very good friend of mine. I’ve said many times that I spent six years as majority leader, and he was minority leader during that entire period, during which we never had a harsh word pass between us in public or in private. We disagreed on a lot of things. He obviously didn’t support Clinton. He ended up running against him for President. But it’s a tough process in any event.

Riley

Sure. I guess I wonder whether your sense was that Dole’s working relationship with Clinton as minority leader—is it more colored by his own personal disposition toward the issues or what he is feeling from his home constituency in Kansas, or is it trying to be representative of where he feels the center of gravity in his party is?

Mitchell

I think it’s all of those things. It’s hard to assign precise numerical values to them.

Riley

Sure.

Mitchell

Any leader in the Senate, majority or minority, Democrat or Republican, has to contend with the reality that in our country we have two very broadly based parties. This is a very large country. If this were a parliamentary system, we’d probably have about nine or ten parties. We have diverse regional, economic, social, other kinds of divisions in our society. The Senate caucus of Democrats tends to reflect that, as does the Republican caucus. So you’ve got a lot of trouble trying to deal with internal conflict and tension, and my guess is that was a factor in Dole’s case.

At one point the conservatives in the Republican caucus gained control of all the leadership positions except the leader. I think they decided they couldn’t defeat Dole so they defeated Al Simpson and John Chafee, some of the other more moderate Republicans, and replaced them with what was seen as more conservatives. So Dole had a constant tension and I’m sure that was a factor. How much of a factor I can’t say.

Riley

I had one additional question in that regard—actually two. When you were working as majority leader with Clinton and legislation was coming to you, did you begin—I guess the partisan breakdown was 57-43. Did you begin with the notion that there were any Republicans that you could reliably go to to assist you and the President in getting legislation through?

Mitchell

Oh no, you couldn’t begin with that assumption. You had to begin with the opposite assumption, that there weren’t any. But depending on the issue, there might be some that you could appeal to.

Riley

The other question was about the House Republicans at the time. What is your sense about the role that they’re playing and the way that the Senate Republicans are reacting to President Clinton? Is that always—

Mitchell

There was an internal struggle going on on the House side. I don’t remember when Newt [Gingrich] replaced Bob Michel—

Riley

It’s before this time.

Mitchell

Newt was the leader at the time. Newt’s a good friend. We worked together a long time—

Riley

I’m sorry, I erred in that. Michel was there for a while.

Mitchell

He’s the whip at this point.

Riley

Yes.

Mitchell

Newt was whip and Bob was the leader. Bob was much more accommodating. I think too much so in Newt’s eyes. That’s a separate story that’s written. You can tell that Newt was increasing in authority. He was much more direct and confrontational with the administration. With the President in the meetings he would always have a fairly lengthy statement of opposition on a variety of things. What makes all this so difficult—not unique to that time—it’s just a constant. You have so many intersecting conflicts within each caucus, leavened by personal ambition. Some guy wants to be a leader. Dole had a tough time with Trent Lott for a long time. It was the same on the House side. Part of the task of leadership is the working through all of these different strands and separating them all and dealing with each one in its own way.

Martin

I suggest we move to the budget, which I’m guessing is going to take a significant amount of your time in 1993. Can you just walk us up to the impasses with the stimulus and talk us through what was happening from the Senate point of view?

Mitchell

As you know, the stimulus package was developed at a time when the recession was more pronounced. By the time it got to the Senate, there were arguments that it was no longer necessary. It kept shrinking in the face of that opposition. There were some Democratic Senators who didn’t believe in it at all and thought that before you dealt with a spending program you’ve got to get the spending cuts.

The same thing happened in the House when they passed the budget resolution first, then the stimulus program. We had a lot of difficulty with that in the Senate. We had a divided caucus. Senator [Robert] Byrd, who had been the majority leader, and was now the chairman of the Appropriations Committee, very strongly advocated the stimulus program and did not wish to yield or compromise further. In that he was enthusiastically supported by some members of the Democratic caucus. But there were other members who just as strongly felt the other way.

The circumstance was compounded by the fact that the program was put together in a manner that clearly did not anticipate the opposition that would develop. There were a lot of individual items that the Republicans were able to pull out and ridicule and thereby denigrate the entire package and the program. It was not put together by someone who said,

Now, this is going to face criticism, so how do I put together the best, most meaningful, criticism-free package I can?

Riley

When you say it was put together by the Clinton economic team, I’m assuming you weren’t getting input?

Mitchell

That’s a subject of some dispute. I honestly don’t know. I think they felt that a lot of individual members of Congress had wanted particular things. They felt they put things in when the Congressmen requested them. Then when it got to the Hill, the Congressmen criticized—well of course it’s a regular thing that a member of Congress will criticize wasteful spending, although he might not criticize the project that he advocated. So you get this seeming inconsistency. Some might use tougher terms to describe it. So it was—

Riley

We can assume that they weren’t then directing all this traffic of communications through you.

Mitchell

Not all of it, no. But I got a lot. I was caught in the middle of both sides. It was a very unfortunate situation, and the President was caught between two conflicting—I’ll limit myself to the Senate now, not the House. There were two conflicting and strongly held views in our caucus. Senator Byrd felt very strongly for it, adopted a parliamentary maneuver that had the effect of either further angering the Republicans or giving them another reason for their anger. You can decide which one yourself. The result was we never did pass the stimulus package, which in a way made it tougher when we got to the major part of the program. But that also in a way made it easier, because a major item of contention had been removed. The concentration then was on the package itself.

When you suffer a defeat like that, you don’t think of it as turning out to be a positive step, but one could argue that it was both. You didn’t want to suffer a defeat early; on the other hand it cleared the table to get to the major item of the budget.

Martin

When Byrd’s parliamentary move fails. There’s a story where he ends his speech,

Where are my troops?

Is this a sense that he went on his own on this move, or was there some expectation that he would have backing from the administration or from Senate Democrats?Mitchell

I don’t know, but it’s quite clear. It was clear at the time, publicly, that not all of the Democrats agreed with him. Senator [David] Boren and Senator [John] Breaux launched a public initiative that was contrary to the position taken by Senator Byrd. There was a lot of disagreement, a lot of emotion on it, a lot of tough feeling. It ended up we weren’t able to pass it. We got to the major item in the budget, which, thank goodness, we were able to pass, just barely.

Martin

One last point on the stimulus package. One thing you mentioned was that the economy seemed like it was shifting, so there was back and forth about whether it was really needed. It strikes me that there’s a question about whether one needs something politically, though, to pass the stimulus, given Clinton had claimed that he was going to try to pass such a thing. How does that play out in the Senate? Are there struggles between folks who recognize indeed we might not need this for policy, but we need this politically to help a new administration?

Mitchell

Sure, that argument was made. We had several meetings with Democratic Senators, caucuses at which this subject was discussed. That argument was made, as well as counter- arguments. There were strong feelings on the subject and there were valid arguments on both sides in terms of both economic policy and political impact.

The reality is, of course, that in such circumstances, people in the position that we were in, that the President was in, almost invariably exaggerate the negative impact of

losing

on this thing. That is especially the case in the Senate, where you’ve got a battle a day. Every day is a new effort. You’re in a position constantly of seeking to put together new coalitions, your own colleagues in the caucus, your Republican colleagues. I can see where, from the perspective of the President and the White House, there would be a more negative view of what a defeat might mean.Those Senators who favored the program certainly used that argument,

You’re letting down our new President—we ought to be part of a team.

That argument was made very vigorously. But others get up and made contrary arguments very vigorously.We’ve got to do what’s right for the country. This isn’t necessary—

and so forth and so on. In the end, it didn’t work. We didn’t get it passed, but once we passed the major budget, this is relegated to history. Nobody cares about it now except you guys. [laughter]Riley

Would you agree though that if that budget had not passed, the implications for the President would have been magnified?

Mitchell

Yes, I agree. There are valid arguments on both sides of the significance of the stimulus package, but it was very difficult to make the same contrary arguments with respect to the budget. It was a major item. It was critically important for the country, for the economy, for the importance of dealing with the deficit and getting the country’s fiscal house in order, in encouraging economic growth and for the President’s future. I think losing the stimulus package was a two-day negative; losing that budget would have been a much more serious permanent negative.

Riley

Can you tell us about your role in getting that passed? That was a razor-thin margin of victory. It must have taken quite an effort on your part.

Mitchell

I devoted pretty much most of my life during that period of time to getting that passed. That was, among many other things, by far the central concern, and I spent a great deal of time with individual Senators seeking to persuade them of the importance, for the reasons I’ve just generally stated, and for a whole lot more. So yes, it was an all-out, all-consuming effort for the entire leadership, and I was very active there.

Riley

Do you feel that you’ve got the authority to step out on your own ahead of the pack to try to craft the necessary compromises on this, or are you reporting all of your moves back to the White House? I’m trying to get a sense—

Mitchell

No, not all. Both would be the case. First, I was engaged in so many different discussions with so many different Senators it would be impossible to report back everything. It would have taken too much time. But certainly general matters; you just had to do the best you could.

It became clear fairly early that the carbon tax would not be approved by the Senate, the Democratic Senators. There just weren’t enough who would support it, so we developed the alternative of a gasoline tax. Then there began an extremely long struggle to get enough Democrats to agree to any increase.

I was later asked, not once, but often,

How did you settle on 4.3 cents?

As though there was some mathematical precision or policy reason for it. The reality is that we had to go through Senators one by one. It’s in the articles. Max Baucus and Herb Kohl, finally, after I don’t know how many hundreds of hours of discussion and debate and argument we had, said 4.3 was as high as they would go, and that’s where we ended up. There was no mathematical precision, no policy reason why it was 4.3 as opposed to 4.5 or 5 or 8 or 10 or some other figure. They both said they wouldn’t vote for a penny more. That’s how we ended up with that.Martin

Are there pivotal Senators that you need to persuade, so that you have a sense that if you persuade say [Edward M.] Kennedy, he’ll carry along two or three people as well? Or is this an individual, one-by-one set of persuasions?

Mitchell

It depends on the issue.

Martin

On the budget though?

Mitchell

Pretty much everybody has his own views on the budget. You begin with the Finance Committee, but you have to deal with pretty much everybody. The reality is it’s like every other group of individuals, 55 or 57 people. A fair number are satisfied and supportive and you tend to gradually focus on fewer and fewer people as you deal with each one and get each one on board or not on board. Senators react in different ways.

On the one extreme you have some Senators for whom everything’s a matter of conscience. You ask them what time is it, they’ll tell you,

This is a matter of real conscience. Let me think about that. This impinges on my conscience.

[laughter] On the other extreme, both numbers small, you’ve got people for whom every vote is a commodity.Okay, you want my vote? Here’s my list.

It’s usually items affecting their home state or something. The vast majority are all struggling to do the right thing, including the two groups I’ve just mentioned. They define the right thing differently, trying to reconcile the inevitable tension between the demands of their constituency and the larger needs of the country.Most elected officials are able to rationalize, through the prism of their own experience and their position. Remember, it was the head of GM [General Motors], Charlie Wilson, who said,

What’s good for GM is good for the country.

That’s a rather blunt way of saying that people engaged in politics tend to go through the same thing.I represent Maine and this is good for Maine, so it’s going to be good for the country,

etc. etc. Multiply that times 50.I found there was no effective punitive mechanism. There are no sticks in that situation. See, Lyndon Johnson had been able to centralize power in the office of the majority leader. That enabled him to wield sticks. But the Senate felt at least that that was a mistake, that he had probably gone a little too far with some of it, so they withdrew those powers from the majority leader. It was basically a rational argument, most of it. This is good for the country. It’s the right thing to do. We need this in the country. Also we should be supporting our new President. We’ve got to help him. He thinks this is the right thing to do. Then dealing with individual arguments—there’s no formulaic approach. It’s one-on-one, each one with a different circumstance and inevitably, as it narrows down, more and more time spent with the remaining smaller group of members.

Riley

Did you ever detect any frustration among the members who were not the usual suspects in transactional politics that they weren’t being given their due attention by the Clinton White House? In other words, you’ve got a group of people who are constantly going up and saying,

Look, if you’ll give me this, then you’ve got my vote.

It seems to me that that creates a dynamic for the universe of transactions to expand to include the people who say,If this character keeps going to get things, then I’m not going to pledge my vote anymore until I can get a military base.

Mitchell

You have to remember none of that began or ended with Clinton. You’re talking about a legislative process that existed independent of who’s President for a very long time. Secondly, what I found is that for most people, lack of consultation is kind of a make-weight argument. If someone doesn’t agree with you on the principle of it, you can say,

They didn’t really consult with me. They didn’t listen to me,

and so forth. No doubt there were occasions when it didn’t happen, but I never felt that was a truly persuasive argument. If you’re a Senator and you’ve got a good argument, you’ve got the means to get it across.Martin

The Republicans filibuster the stimulus and that basically kills it. What about when we’re leading up to the actual budget vote? Are there efforts to derail that we don’t know about?

Mitchell

I think they’ve all been pretty well documented. It was just really all-out opposition. They were very unified. The reality is, of course, it’s much more difficult to achieve unity among the majority, of which I have a part. When you’re in the minority, cohesion is much more readily obtained than when you’re in the majority.

I think also, at least up until that time—it may be different now—Republicans tended to be more homogeneous, a smaller party, less a coalition of different national and regional interests than the Democratic Party. They had an easier time attaining cohesion than we had at that time for all of those reasons. They were solid. Every single one of them voted against it, every single one. I’ve given the speech a thousand times in which I said that every single Republican voted against it and almost all of them said that if Clinton’s budget passed, interest rates would go up, unemployment would go up, the economy would tank, job creation would go down, inflation would rise.

In other words, what they said is all the bad things would go up and all the good things would go down. And of course as we all know, the opposite happened. All the good things went up and all the bad things went down. They were 100 percent wrong in terms of their issue now. Their argument later became that other circumstances caused it. In other words, they made the argument that if Clinton’s program is enacted, all these bad things will happen. They didn’t say anything then about other circumstances. But because things turned out well, they made the argument of other circumstances. Not that Democrats would have done any differently had we been in their position. It became pretty clear that we could not count on any Republicans.

Riley

So you didn’t have any hope along the way that you might bring—

Mitchell

Maybe early. I think early we would have.

Riley

Who might have been the likely suspects?

Mitchell

I had a very good personal relationship with John Chafee. My colleague, Senator [William] Cohen from Maine, Arlen Specter. There were a few so-called moderate Republicans. But even they, it became clear—I can’t pinpoint the date, but well before the vote—that if we were going to pass this, it was going to be with Democratic votes.

Riley

Those Senators you just mentioned, their opposition was driven strictly by policy concerns or—

Mitchell

I don’t know, probably a mixture of everything. Probably the arguments I’ve suggested were made in favor of it. If you take the mirror image, they probably were made on the other side. It’s bad for the country and we don’t want to let this guy get off to a good start, so forth and so on, probably a mixture of substantive and political reasons.

Riley

Let me ask a related policy question. To what extent was the 1990 budget an important predicate for what happens in ’93? Is that something—

Mitchell

Yes, it was very important. The ’90 budget fight was very tough on everybody. It was very difficult. There were a lot of hard feelings that lasted for a long period of time. There was tremendous internal disagreement among the Republicans. I recall very clearly going down to the White House for announcements when Bush was President, when Gingrich balked at the last minute. Another time [Robert] Packwood balked at the last minute. They had a lot of internal difficulty with it. We had internal difficulties as well, not as much as they had. It was just very tough for everybody.

As I said, I won’t repeat that whole story here about the so-called breaking of the tax pledge, but you’re right. It left a legacy that was tough to overcome.

Riley

But the policy legacy. There were certain things put into place that you built on in the ’93 budget. I’m not an expert on budget politics.

Mitchell

We tried to develop this whole notion of pay-as-you-go and combining spending cuts with revenue increases. I can’t think, though, that there was any real beneficial angle, any beneficial consequence. I think the consequences were largely hard feelings and the pervasive attitude,

These guys forced Bush into reneging on his pledge, thus paving the way for Clinton’s election, and we’ll be darned if we’re going to help them now.

Martin

This may not be something that you can answer, but I’m curious—moving into the budget and the Republicans holding a no vote, what tools does Bob Dole have to keep Republicans together as minority leader? Is it just persuasion, or is he—

Mitchell

First off, I think the vast majority of Republicans in principle were opposed to the tax increases. If there’s one thing Republicans believe in it’s that there should be tax cuts, not tax increases. Secondly it was tax increases on the wealthy. If there’s one thing they believe in more than tax cuts, it’s tax cuts for the very wealthy, because they advocate the economic argument that that’s how you spur the economy. You’ve got to give more money to the wealthy because they invest it and that creates jobs for the rest of the people.

I think most of them really believe that. I don’t think it’s just saying it for political reasons. They’ve taken a lot of flak over their commitment to lower taxes for the very wealthy. While there may be a pragmatic factor there—they get a lot of contributions from them—I think for most of them it’s a genuine belief, something they sincerely believe is right for the country. I don’t think it would be very hard to persuade any group of Republicans, certainly not Republican elected officials, to oppose tax increases.

Add to it the other factors that I mentioned, the politics of it and so forth, but I think they were doing what they genuinely believed to be right, just as we were doing what we genuinely believed was right. We hold a contrary view. While I personally accept the economic premise that you want to encourage people to invest, and I favored a maximum tax rate that was lower than what some Democrats felt, I never accepted the Republican argument on that issue.

Riley

At one point in the spring of ’93—

Mitchell

Let me just say we had a debate on that, I remember, in the White House, on the tax rate. I had been actively involved in the passage of the 1986 tax reform bill, when the maximum rate, which had been 70 percent and had gone to 50, was brought down to 28 percent. Reagan originally proposed the plan that was to simplify the structure by reducing the number of rates and having a maximum rate of 35 percent. That effort was foundering. I’m giving you this as a background to the Clinton discussion.

Six members of the Finance Committee—three Republicans and three Democrats, including myself—got together to try to put it back together again. We did, but I dissented from one provision, which was to bring the maximum rate down to 28 percent. My argument was that Reagan himself said 35 percent. Why do we have to go to 28 percent? But Bill Bradley was one of the other three Democrats, and his view prevailed. We had a long discussion in the Democratic caucus about it, a debate really between him and me. His view prevailed. The Democrats split about half, split in my view that the maximum rate should be 35 percent. About half went with the total package that brought it down to 28.

Gradually, in the Bush one term, it came back up. When we were drafting Clinton’s economic package, we had a big discussion in the White House about where the maximum rate should be. Several Democratic Senators wanted it at 40 percent or 42 percent, and I was adamantly opposed to it. I said,

Look, we said we ought to be at 35 percent, and that’s where we ought to stay.

We then settled on 36 percent. But to get more revenue and to accommodate the argument of a sizable number of Democrats who wanted a higher rate and didn’t agree with me, the administration accepted. I think this came out of the House Ways and Means, but I’m not sure of this. The President accepted a so-called 10 percent surcharge for people with incomes of over a million dollars, which took the maximum rate up to 39.6—kept it right under 40. The ostensible rate was 36 percent, but the surcharge brought it up to about 39.6. We had a long discussion about that.

Riley

Do you remember the President’s positioning in this?

Mitchell

I can’t. I do remember the individual Senators with whom we had a spirited argument, but I’m not going to get into it here now. No rancor, no hard feelings, but a very spirited argument. But a couple of them argued very strongly for 40 percent, even a few for 42 percent. We were all over the lot. But I think where it came out was 36 percent, and then this surcharge of 39.6. That happens to be my view. I think the mid-30s is about the right range for the maximum rate.

Riley

Since you raised it in this context, let me ask you. Do you have any specific recollections of meetings with the President in the White House like this on any other issues that you could tell us about?

Mitchell

Yes. We had a lot of meetings.

Riley

Is he a take-charge person in these meetings?

Mitchell

Oh, yes. Very knowledgeable, far more knowledgeable than any President I ever dealt with on the details of the issue. That of course became much clearer in healthcare. He was very knowledgeable. Usually when you get out of the White House—well, not usually, there is no usual. I’ll just tell you my experience.

When you went down with Reagan, he was a very nice guy, but he would really begin with a humorous anecdote, end with a humorous anecdote, and pretty much turn it over to his aides in between, make occasional comments.

With the first President Bush, on the subject of foreign policy, particularly the war in Iraq, he was active, engaged, led and dominated the discussions, but when it was domestic, economic issues he became disengaged. Let me phrase it a different way. He was much less engaged and would yield to his aides. So the public perception was the private perception. He really was more interested in foreign affairs. He would call it unfair to say he was disinterested, and I think it would be unfair, but he clearly wasn’t as engaged and interested.

With Clinton, on the other hand, he was very much interested in domestic policy issues, the budget, healthcare, and so forth, and would engage in detailed debates. Ordinarily when you went down, if you had a committee chairman with you, that was their area. They would know all the details. But Clinton knew the details as well or better than any committee chairman on most issues. He was obviously the most active, engaged, best prepared in terms of specific knowledge of the issues of any President with whom I dealt.

Riley

Is that a disadvantage for a Senate majority leader?

Mitchell

Oh, no, no. To me it was always an advantage. I didn’t have to carry the argument, particularly on subjects where I didn’t know as much as he did. It was very helpful when trying to persuade people. Sometimes he’d go too far, get too much into the weeds. That’s one of the byproducts of a lot of knowledge, that you have to demonstrate it. But all in all I think it was very good, very helpful.

Riley

This engagement and grasp of the issues was equally so on the foreign policy side as the domestic side?

Mitchell

We didn’t have quite as many foreign policy issues in the two years that I was there with him because the issues weren’t as ripe or evident, and I was not there during the later time, when he had a lot of serious issues.

Riley

Going back to the question I was going to raise—in the spring of ’93, you were publicly on record that healthcare reform ought to be included as a part of the budget reconciliation process in that first year. What happened there?

Mitchell

Too many of our colleagues didn’t want to do it. You have to understand the reconciliation process. It is a mechanism for overriding the Senate rules, which permit unlimited debate and unrestricted amendment to facilitate enactment of that limited measure. There are rules that purport to limit it, to exclude extraneous matters. In retrospect, when the Republicans later took over, they threw the rules out the window. They began using the reconciliation bill for literally anything they wanted to put in it. At the time we were involved, it wasn’t quite that elastic. There was sentiment for doing it, because this is a way to get it done. There was sentiment for not doing it, because it would violate the rules and establish a bad precedent.

The other reason for not doing it is that it was clear to me as a supporter and a proponent that the bill had not been sufficiently vetted down, that you had to go through a hearing process and a debating process to get it to something that if you passed it, it would work. The legislative process in our country does not lend itself to large, complex undertakings—very hard to get through, very easy to pick apart, as happened with the healthcare bill.

It’s much easier to pass limited—either limited in the sense of general words, or limited in terms of subject matter. When you try to combine complex subject matter with a detailed prescription thousands of pages long, it becomes very hard in the legislative process. Ultimately I concluded that first off, it probably wouldn’t be right under the rules, and secondly, it wasn’t going to be good for the country if we somehow were able to pass this bill that needed a lot more work on it.

Riley

I wonder if you could give us an overall assessment of that healthcare reform effort. Where did that go awry?

Mitchell

I may be off a little bit on my dates, but in November of ’93, the President finally sent up a bill that Dick Gephardt and I introduced, Dick in the House and I in the Senate. This had been a product of a great deal of effort led by Mrs. Clinton and Ira Magaziner. A very complicated and what I would call a coalition of interests in support of reform was put together. Although not much noticed, I think it was December, probably just before Christmas, a Republican bill was introduced. John Chafee was the principal architect, but he had about 20 Republican Senators, including Bob Dole, on the bill. Chafee and I had a number of discussions over this period of time, the winter of ’93-’94, about how we might be able to put together a reasonable package.

There was a Finance Committee retreat that we held in one of these conference centers outside of Washington, just on healthcare. I genuinely felt that there was a reasonable chance that we could put together a pretty decent bill based upon a compromise between the bill that we had put in on behalf of the President and the bill that Chafee had put in in December. It was for that reason, I think it was in April, when Clinton offered to nominate me for the Supreme Court, I declined. I said to him,

I really think we have a chance at this.

He was anxious to get some action on the healthcare bill. We agreed that I would stay put and try to push this. I had just announced in March that I was not going to seek reelection. So I said,I’d just feel wonderful if in my last year we could pass comprehensive healthcare reform, so I want to stay and get that done.

Over the next few months, however, the prospects dimmed for a variety of reasons, which I’ll get into. First, the interests against organized and conducted a skillful campaign of advertising outside—the famous Harry and Louise insurance company ads. And inside, with the Republicans working to undermine it, which they did with a considerable amount of success. You could see the support outside and within the Senate gradually declining, to the point where when the Finance Committee got to the bill, I think it was in July, I joked to Chafee, who was a very good friend of mine,

I’m going to offer your bill as an amendment and force the Republicans—

Oh, gee, don’t do that,

he said.That will be really embarrassing to do that.

The Republicans, including those who had co-sponsored his bill, had moved away from it. As we moved toward the center, they moved further away. We never were able to narrow the gap. Although both sides were moving, they were just moving in the same direction and therefore not closing the gap.A second reason was that one of the problems was when you draft legislation with a coalition of supporters, their interest is in their provision in the bill. They don’t care about the rest of the bill. You had all of these supporters not wanting any compromise on their provision. One of the best examples was mental health. There had been a huge gap and a sharp variance between the treatment of physical ailments and mental ailments before, and we went a long way in the bill toward dealing with that and establishing a sound basis for treating mental health in much the same way. But it wasn’t 100 percent of what that coalition wanted, it was about 80 percent. They spent all their time trashing the bill because it wasn’t 100 percent of what they wanted as opposed to 80 percent.

It was the same way with the teaching hospitals up there. One of the reasons that Senator [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan had so much difficulty with the bill was that you had very large payments made through Medicare, ostensibly for medical education, which in fact go to reimbursement for major urban hospitals for the treatment of indigents and other poor people and education in that regard. They were treated very well. They wanted better treatment. In the absence of better treatment, they were trashing the bill. In fact, at one point, Senator Moynihan, who was a strong advocate of healthcare reform, introduced an amendment with Senator Packwood to increase the amount going to them.

So the White House’s effort had resulted in a broad coalition, but a coalition of groups that was interested primarily, and in some cases exclusively, in their section of the bill, and weren’t about to come out and support the bill until they got exactly what they wanted. If you gave everyone exactly what they wanted, you’d have a bill that was politically infeasible anyway.

Riley

Sure.

Mitchell

So the support was not strong, whereas the opposition was unified, focused, very intensely dedicated. It became obvious that we just weren’t going to be able to get it done over a longer period of time. Finally I received a great deal of very sharply conflicting advice from Democratic Senators. There were some totally committed to proceeding, saying,

Let’s keep going.

There were a substantial number of others who said,Look, this is hurting us. It’s hurting my campaign. It can’t pass and you’ve got to pull the plug on this.

So back and forth we went. Finally it became clear that we couldn’t do it, although we had one after-the-fact effort after we pulled the plug. It was a combination of things.It’s probably not possible to pass a measure of that type in the Senate. You could probably pass something that is comprehensive but simple national health insurance. Make Medicare universal is the best way to put it. People understand that.

You can probably pass incremental measures, provide insurance for children, provide insurance for specific categories. To put together these hybrid bills where you build upon the employer-based health insurance that we have, you adopt a varied measure California sort of thing. I admire what [Arnold] Schwarzenegger’s trying to do, but it’s a Rube Goldberg mechanism, and it’s hard to see how it’s going to effectively work. Much the same criticism was, and could be fairly leveled, at the thing that the White House had put together.

I took the bill at one point and I tried to rationalize it. I did in fact, some. It was still very long and too complicated for everybody. It was a combination of things. Not well put together, not well presented, certainly not strongly supported, and with a ferocious and well organized and very expensive effort at our position, which was, I have to say, replete with exaggeration and false statement, but nonetheless effective.

Martin

How much did activities in the House affect what you were doing? [Daniel] Rostenkowski is under indictment at this point. The House isn’t getting bills out of committee on healthcare. Is that a signal that you take or the Senate takes?

Mitchell

We always knew it was tough. I would call those confirming factors rather than revelatory. They didn’t tell us anything new. They told us what we already knew—this was going to be really hard. All around it was a tough year. Mrs. Clinton did a nice job. She knew the subject, she was very good, but in the end it didn’t have much effect one way or the other.

Riley

Did you circulate with Mrs. Clinton when she was making her rounds on the Hill? Did you go with her?

Mitchell

Oh, yes, sure. I brought her into the Senate.

Riley

Can you tell us—

Mitchell

She did a good job, meeting members of both parties, meeting with Democratic Senators. She understood the issues. She did a nice job, but in retrospect the premise of putting together a bill with all these different supporters—and I would regularly be asked by the White House to go talk to these groups to reassure them. I did, but it was obvious to me—you’ve got to get people who are committed passionately to the principle of reform, foremost, and then to their interest as a part of that. But groups were all—they’re good friends, they’re good people, but they were fighting for what they believed necessary, and that was their issue.

Riley

In retrospect, was it a mistake to put Mrs. Clinton in charge of this program?

Mitchell

I don’t think the outcome would have been different had she not been.

Riley

Did you ever get the sense when you were making the rounds on the Hill that people were pulling their punches because they were talking to the First Lady on these issues?

Mitchell

No, there was nothing personal in it. There were disagreements. What happens in those things, of course—you have a joint caucus. The ones who are most strongly opposed tend not to come. They don’t want to listen to her talk about something they already know they’re against. You might get a few people in there to discuss and debate the issue, but reality is you don’t have the direct clash of views because people who don’t agree and aren’t going to be persuaded tend not to come.

Riley

One of the things we very routinely hear across the projects is that there are an awful lot of brave people, and I won’t say members of the Senate, but an awful lot of brave people who start in a limousine on Capitol Hill thinking they’re going to go to the White House and tell the President off. They get in the Oval Office and there’s something that happens there—

Mitchell

That’s true.

Riley

It is true. You found that to be true with President Clinton, also, that there were people who didn’t feel comfortable giving him the unvarnished view of things?

Mitchell

Some did, some didn’t.

Riley

That’s the basis of my question about Mrs. Clinton. Were there people that, because she’s an extension of the President in a way that nobody else is—

Mitchell

I don’t recall. As I said, I think it’s more that people just didn’t come. The ones who felt most strongly opposed didn’t come.

Riley

The President in the speech in the fall unveiling his package pulls out a pen and says if he doesn’t get universal coverage he’s going to use it in a veto. Was that a mistake? Did you advise him one way or the other about that?

Mitchell

No. The truth is in retrospect, I don’t think any of that had much impact. It’s hard to conceive of a set of tactics that would have produced the desired result.

Riley

Did you get feedback from the members about that? Were there people who were put off by the—

Mitchell

The pen?

Riley

Yes.

Mitchell

No, not that I can recall.

Riley

With the healthcare package, part of the conventional wisdom is that the White House had a very closed off process for creating a bill that then gets sprung fully formed on Capitol Hill that’s not a Hill measure. Does that resonate any way with your—

Mitchell

There was a lot of discussion about that,

Send us some general principles.

I think [George W.] Bush, the current President, thinking he has learned from the Clinton experience, has tended to do that. You can argue that both ways. It probably depends upon the circumstances. In some cases you’re better off with general principles.It might have been better to send up a bill of general principles on healthcare rather than a detailed legislative proposal. I doubt the result would have been any different, but one never knows.

Riley

You had a high comfort level with the degree of consultation that was going on with Ira Magaziner’s task force or—

Mitchell

I had no problem with the process. I had a problem with the product—too big, too complicated, too difficult. That was the problem.

Riley

That could have been fixed earlier?

Mitchell

I don’t know. The subject lends itself to that, unless you have a solution that you’re going to have national health insurance—trying to do it by—look how accidental the system is. Healthcare provided by employment was an unintended consequence of wage freezes during the Second World War where you had millions of men who had left. You had a huge demand for workers, but wages were frozen. In order to induce people to come to work for them, businesses began to offer the benefit of health insurance. That’s how employer-based health insurance occurred. It wasn’t a grand scheme. There was no Ira Magaziner at the time who thought this up and said this is a good way to provide health insurance.

So you have a system that developed accidentally. It’s a complex mixture because it’s private enterprise, but the economic transactions are not subject to the same economic forces as most private transactions are. It’s one of the few economic transactions in which the seller determines what the buyer will purchase. I spoke at an automobile dealers’ and said,

Wouldn’t it be great for you guys if the car dealer told the guy, ‘You don’t need just a sedan, you need a pick-up truck and an SUV [sport utility vehicle] too,’ and the guy said, ‘If you say so, doctor, that’s what I’ll do.’

So the normal laws—there’s no bargaining, no looking around. The normal laws of economics don’t apply, so you get this system developed in an almost haphazard way that’s incredibly inefficient. Although paradoxically it produces the highest quality of care in the world for those who have access to it. It’s a very difficult subject. You’d have to do another full oral history on healthcare.

Martin

You announced, I guess it’s March of ’94, that you’re not going to seek reelection. How does that affect your position and stature as majority leader? Does it create a lame duck effect, or does it have no bearing whatsoever?

Mitchell

I’m sure it did, but nobody ever said to me,

I’m not going to do anything because you’re not running again.

It’s fine. I had a good—I remember the date, it was March 5. On March 4 I taped a five-minute announcement that was going to run on the statewide news. It just so happened that on March 4 I had dinner at the White House and I sat next to the President. Toward the end of the dinner I said,Look, I’ve got something I want to tell you. Can I see you for five minutes after?

Sure,

he said. I told him and we chatted for about two and a half hours. He tried to persuade me to change my mind. I said,Look, I’ve already made up my mind. Like I said, I’ve sent out this tape to all the television stations.

We had a good chat. He was very nice about it. Then he walked me down through the White House all the way with his usual charming way. The next day I announced. I can’t measure the effect. I’m sure there was some.Riley

Did you talk at all about whether you might come back in some capacity?

Mitchell

He said to me,

Look, if I ask you to help on something, would you consider it, or are you just sick of politics?

I said,

I’m not sick of politics, I love it. I love being Senate majority leader. I just made up my mind.

I actually had made it up a long time before, that I would serve a limited time and I would leave. In addition, I had decided to remarry. It was partially personal. I had been divorced for a very long time. It was a combination of factors. I said,No, I’d like to do something.

Subsequently, a few months later, he asked me to go to Northern Ireland. I ended up at Northern Ireland, I think, as a product of that conversation.Riley

Had you talked to him about the Court vacancy in ’93?

Mitchell

No.

Riley

Had they approached you at all about that one?

Mitchell

No, just ’94. I can’t remember the date, probably in April, about a month after I announced. He was very direct about it. He said,

I’d like to nominate you.

I said,

Gee, that’s an honor, I have to think about it.

A couple of days later I called him. I said,I’ve thought about it.

I called him for a meeting and I went down to talk to him and told him. He understood it. He really did want to get something done on healthcare. I think I probably encouraged him by saying I thought there was a reasonable basis for a compromise with Chafee based on the two bills. I genuinely believed that. I can’t tell you at what point in time prior to the summer, when I became persuaded that I misjudged it, that in fact there wasn’t a realistic basis, or if there was, the circumstances had changed. More likely that’s what really happened. The circumstances changed and it was no longer possible.Riley

We’ve got about 10 more minutes. Did you ever second-guess that decision to turn the President down about the Supreme Court?

Mitchell

No. The one thing I learned when I was a federal judge—when you’re a district court judge—I tried a lot of cases as a U.S. attorney and as a trial lawyer before, but when you’re a judge you’re called upon to make dozens of snap decisions. A fellow asks a question, a guy gets up and says

objection.

Within seconds you have to say overruled or sustained.At first, going to bed at night I agonized over every single one, Gee, did I do that one right? Did I do this one wrong? I’ll never forget my first trial. I didn’t get a night’s sleep for about two weeks. I finally said, You’ve got to do the best you can, and you’re bound to make a certain number of errors, but otherwise you’ll be paralyzed. I’ll be a walking zombie if I can’t sleep, if I worry about every decision I make. I developed the frame of mind that you do the best you can under the circumstances that exist based on the factors that you’re aware of, and then you rest.

Although I have to tell you, last night I was reading through your preparation materials for this and I was chatting about it with my wife. She was then not my wife. We had planned to be married. We were married later that year. I said,

What do you think would have been different if I’d gone on the Supreme Court?

She said,Well, the first thing would have been we wouldn’t have the two kids that we have.

That probably was a good thing in retrospect, if you measure it on a larger scale.Riley

Exactly. Were there any discussions then about future vacancies?

Mitchell

No.

Riley

In some of the stuff we’ve read, I think in this packet, and heard, the chief justiceship gets floated in these discussions.

Mitchell

Not in my discussions. There may have been press speculation.

Riley:

What about the second term? Did they ever approach you about coming back? Were there positions in the administration you might have taken?

Mitchell

Yes. Erskine Bowles called me once and asked if I would accept appointment as Ambassador to the United Nations. I declined. Prior to that, President Clinton asked me to come to the White House for a meeting on the position of Secretary of State when Warren Christopher left and Madeleine Albright was appointed. But either he or his aides suggested to me that it was a choice between myself and Madeleine Albright. I spent two or three hours with him in the White House. I told him I would not campaign for it, which I didn’t do, but I would accept it if offered. Of course, they decided to appoint Madeleine. Those were the only two positions that were discussed. One was offered; one was not.

Riley

Looking back on the time, you’ve already told us you’re not a guy who second guesses, so I can’t ask you if you have any regrets about the period.

Mitchell

The healthcare bill I might have terminated a little sooner, in retrospect. It was pretty clear to me that we were not going to be able to succeed. The Republicans were completely united in opposition and there was enough division among Democrats to make it clear that we couldn’t possibly muster 60 votes even to get the bill up. First off we needed three Republicans to bring the bill up and to get moving on it and to get anything done. It became clear that we weren’t going to get it. We probably would not have even gotten a majority. In other words, we would have lost all 43 Republicans and probably more than 7 Democrats trying to move the bill. So I might have done that a little sooner.

Riley

Are there any lessons from your experience? It was a long time between Democratic Presidencies with the Democratic leadership.

Mitchell

In the span of my career—I was appointed in May of 1980, so I was there the last eight months of Jimmy Carter’s Presidency.

Riley

Assuming we have another one in some close proximity in time, are there some lessons you can draw?

Mitchell

None that aren’t obvious to everybody, I think. I spoke at the Democratic caucus last month, in January, when they met. I talked a little bit about my experiences, what has to be done and the difficulties of doing them are pretty obvious to everybody.

Riley

Your sense of the Senate as an institution—did you leave it with a sense that it was a functional place, or were there some things that you think as a majority leader if you were made emperor for a while and you could tinker with the mechanics that would help the institution function better?

Mitchell

Sure, if I were emperor for a day, I would tinker with the mechanics and change some of it. But look, although I didn’t feel this way when I was majority leader because I was trying to get things done, I’ve thought about it a lot since. The Senate is a microcosm of the American system. It’s the ultimate in checks and balances. I speak at universities a lot. I tell students the founders decided that the most effective way to prevent bad things from happening was to prevent anything from happening, and the Senate is the ultimate expression of that thought. You make it hard to get things done.

The results have been pretty good. We didn’t pass some bills that I thought we should have passed—campaign finance reform, healthcare reform. But in the long haul, the system has worked reasonably well to preserve individual liberty, to provide opportunity for people. If you measure over the arc of the nation’s history as opposed to framed reference of one individual’s Presidency, of Bill Clinton or my six years as majority leader—if you get past the frustrations, you think it works pretty well. Some you should change and some you wouldn’t.