About this episode

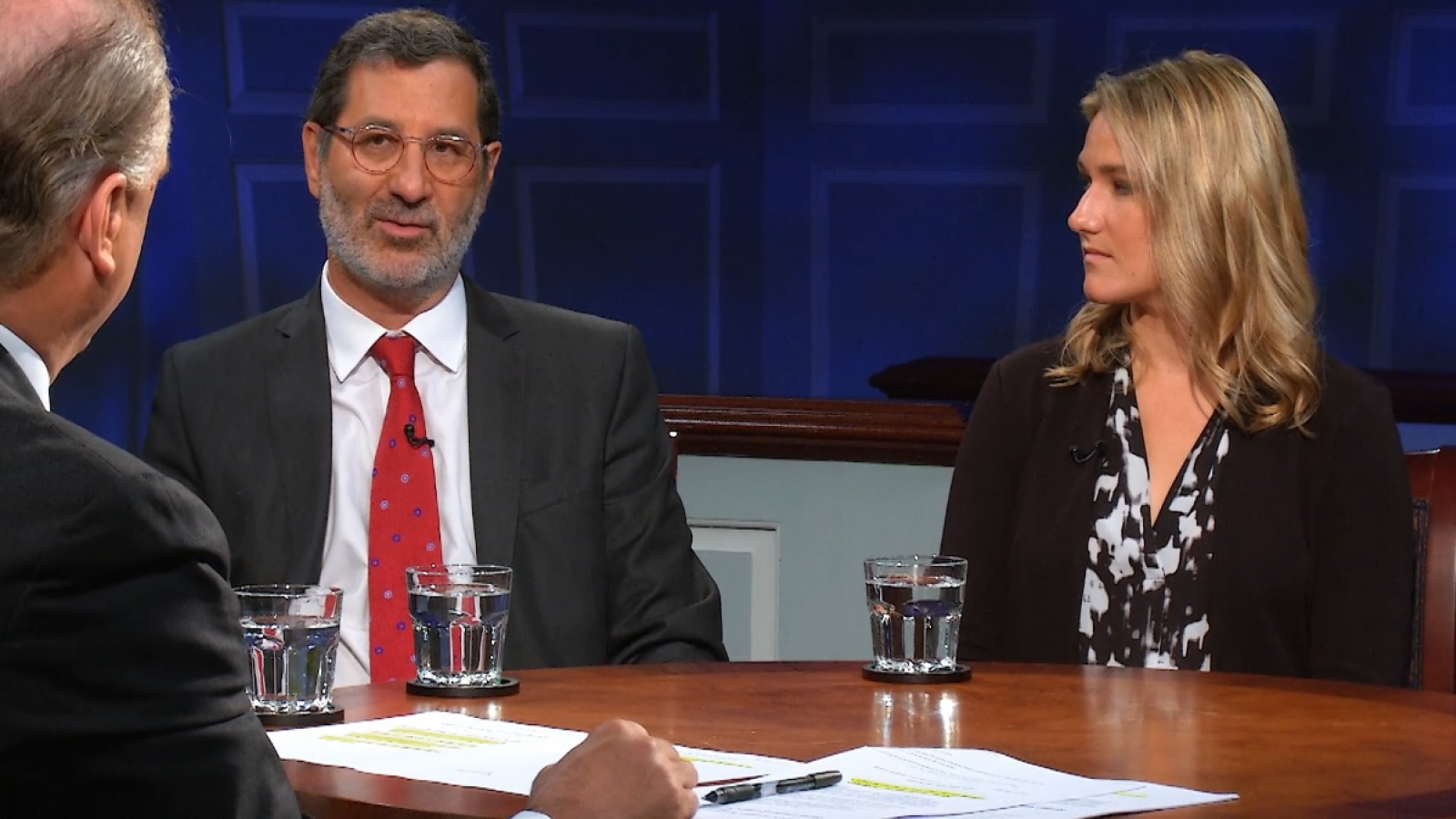

Stephen Engelberg, Vera Bergengruen

Hosted by Douglas Blackmon

These are challenging times for journalists. President Trump and others political figures critique reporters relentlessly. Partisan media organizations attack each other. The public’s confidence in the media is low. And yet one of the reasons for the hostility may be that journalists are raising serious questions about the president’s past business dealings and have pointed out sharp contradictions between his promises to “drain the swamp” and his actions in office. Our guests this week are two journalists who have been in the thick of those revelations, Vera Bergengruen is a national security correspondent for BuzzFeed News and previously covered the Pentagon, the White House and the 2016 election for McClatchy Newspapers, where she was part of team a Pulitzer Prize winning investigative team. Stephen Engelberg is the editor in chief of the groundbreaking non-profit journalism project, ProPublica. Previously he worked eighteen years at the New York Times and was a managing editor of The Oregonian in Portland.

The Presidency

The President and the Press

Transcript

00:41 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. When it comes to American politics, especially around the White House, these are wild times. President Trump and others political figures attack journalists relentlessly. Partisan media organizations attack each other almost as vigorously. Surveys suggest that the public’s confidence in the media is as low as it has ever been. One of the reason for all that hostility from the president may be his frustration with journalists who have raised serious questions about his past business dealings, and pointed out sharp contradictions between his promises to “drain the swamp” of the alleged incestuous relationships between lobbyists and policy makers in Washington, D.C., and the reality that, once in office, President Trump suspended tough ethics requirements of the Obama years, packed his administration with lobbyists, and been stung by revelations about his own potential conflicts of interests and business relationships of some top advisors and family members. Our guests today are two journalists who have been in the thick of those revelations, Vera Bergengruen is a national security correspondent for BuzzFeed News and previously covered the Pentagon, the White House and the 2016 election for McClatchy Newspapers, where she was also part of team a Pulitzer Prize winning investigative team. Stephen Engelberg is the editor in chief of the ground breaking non-profit journalism project, ProPublica. He worked eighteen years at the New York Times, including stints in Washington, and Warsaw, and before ProPublica was a managing editor of The Oregonian in Portland. Thank you for being here.

Stephen Engelberg: Thank you.

02:12Blackmon: Let’s dive right into the substance of the scandals and the controversies that have bedeviled the Trump White House. You guys have both been very involved in reporting on different dimensions and some of the same dimensions, but, Vera, where do you see all of this going? What does it add up to?

Vera Bergengruen: I think it’s a matter of, right now—what’s happening a lot with the investigation is following a lot of the financial dealings. It’s kind of going down to the—as they put more and more resources into looking at the different people connected to Trump, to the Trump Organization, to different foreign entities that may have had influence in terms of following the money, in terms of just who paid whom, what interests may have been influenced, whether they made any decisions that might have been influenced by that money coming to them from Turkey, from Russia, from former Trump advisers, all these different things. I think there will be a lot of trying to see a window into their intent, into whether they made decisions influenced by that, and that’s where I see it going for the most part.

Engelberg: Well, I think you have two different levels here, and they’re both important. There is a looking-back aspect—and, by the way, yes, we’re in this netherworld, but if you think about the sort of chronology of Watergate, seven months into Watergate we didn’t know so much either.

FACTOID: Nixon resigned August 8, 1974, two years after Watergate break-in

So I think, you know, every day, every week we’re learning things that are quite startling about Trump and his business history and his campaign. You know, the latest business, that the presidential candidate of the Republican Party was negotiating a business detail in Moscow with sort of regime-connected financial figures while he was running for president and opining on things relating to US-Russian relationships, that’s unprecedented, as far as I can see, in American history, so that is going to be an ongoing story. At ProPublica, we’re also thinking hard about the going-forward story, because there are radical changes occurring across the US government in terms of regulation, in terms of approach to—to every imaginable thing. I mean, you know, transgender in the military, the environment, climate change, business regulation, we—you know, who even remembers what’s happening with Dodd-Frank and the implementation of that, the healthcare system. So I think it’s very important that we not lose sight as journalists of the important effect that government has on people’s lives and that we need to cover the changes in that as well, so there’s—it’s a multifaceted story right now.

4:28 Blackmon: So let’s work through some of ProPublica’s work around that, but first let’s talk about the—Michael Flynn and Russia, this very complicated story that’s really multiple stories that I think people get mixed up about very frequently. Is it about Russian tampering with the election? Is it about the idea that Russia actually threw the election decisively, that what they were up to actually changed the outcome somehow? Is it about normal conflict-of-interest of officials who happen to have ties to Russia? What’s the story there?

Bergengruen: I think a lot of it was just not having revealed that he had these business deal—that he had these ties to them, that he spoke in 2015 at a gala, set next to Putin, that he, again, was a registered foreign agent when he was making decisions that he hadn’t disclosed yet. The problem is just, mainly, that it wasn’t disclosed and then that, when people asked about it when it came to light, he comple—there were no answers. There was no transparency, and I think a lot of—going back to the White House, a lot of the biggest issues were the fact that they were repeatedly warned by people that he had these dealings, that he had this background, as he was in classified briefings, as he was making decisions for the White House. And, um, the—you know, the question really is whether Trump or Pence or all these people knew, and the White House over and over has said that they didn’t know. They tried to get out of it, um, and I think a lot of it is did they know that he was connected to these people, uh, because, you know, he was—again, he was sitting in in meetings when Trump was talking to Putin for the first time. He was making decisions as a National Security Advisor, and, at the same time, what nobody knew was that he was being paid by a lo—a Russian-connected Turkish businessman and all these different foreign interests, and I think a lot of it—my work has been looking backwards and seeing how he could have been influenced that way.

FACTOID: Flynn resigned as Trump’s national security advisor after 24 days

6:19 Blackmon: That’s also where we then get into not just the conflict of interest of General Flynn but also, again, the question of what did the President know and when did he know it and to what degree did—to what degree would he had been involved in trying to obscure what had actually happened. I’m just curious as—this is asking you to go a little beyond the straight facts that you’ve reported, but I’m curious about, in both of your cases, the—your reportorial instincts. Is it plausible that General Flynn would not have said, “Hey, soon-to-be President Trump, uh, by the way, that’s me. You know, I talked to the ambassador about that yesterday.” Is—is it plausible that that wouldn’t have happened?

Engelberg: I think we’re in a realm where we need to be very careful about what we know and what we suspect because there are differing interpretations that you can have of what we’ve seen. Certainly, one interpretation, which the Democrats have put forward, is that this is the behavior of people who have something to hide. This is guilty behavior, um, and I think that’s entirely possible. If you had asked me several months ago, “Would we ever see an email where key members of the Trump campaign were offered dirt from Moscow on Hillary Clinton and took a meeting?” I would have said, “They’ll never right that down. That’s ridiculous. That’s never going to occur.” And yet we now see the evidence of that. On the other hand, we have a president—and we all saw this—who, when he’s standing in the eclipse and somebody shouts, “Don’t look at the sun,” he looks at the sun, because that’s who he is. And I think, over and over again, what we see is that if somebody tells him not to do something, if it’s going to annoy the media, the mainstream, uh, political views in Washington, he will do it, and he will then double down on it when he’s caught doing it. So, you know, I could see, you know, a scenario in which the Comey firing and all the things that we now are familiar with are part of a very massive cover-up. You know, why does the president of the United States say to the head of the FBI, “Can you let this go?” Why would he say that? On the other hand, um, we have a man again who seems to just delight and glory in doing—first of all, whatever Obama did, he does the opposite. Whatever anybody tells him to do, he doubles down, triples down, quadruples down. I don’t think anybody would say that his comments post-Charlottesville were politically astute, but once he was told he shouldn’t have said them this is what he does. So I don’t know. I mean, I think we’ve got to be very careful not to get ahead of the facts and get ahead of the story.

8:36 Blackmon: Is this the—is General Flynn the sort of person who would have been engaged in these sorts of things and just kept it all to himself and, uh—and been not particularly concerned about getting credit for, uh, navigating a sequence of events that President Trump was then very happy about? Is that—is it plausible that that would have happened just based on your instincts about his personality?

Bergengruen: Right. Well, I can’t really speak to that in that sense, but, uh, it seems that just as someone we know was engaged in these conversations, was sympathetic to these kind of interests, and who had every reason to believe that the president was as well in some ways, just because—given his tone during the campaign, this openness to dealing with Russia, this kind of almost laudatory tone when he talked about Putin. I don’t—I can’t speak as to whether that sounds like something he would have done, but I would imagine that he—given what happened after, it casts it into doubt, but he would have thought that there was a receptive audience for that kind of talk.

Blackmon: If there was something in this sequence of events that really was inappropriate or seriously wrong—or is it plausible that he just didn’t understand the rules?

Bergengruen: No, I think he understood the rules for the most part. I mean, he—he’s an old veteran of all of this, and, you know, we can tell because his person—his lawyer reached out to the White House and told them, you know, “We’re thinking of registering as a foreign agent.” This was before the inauguration. We know that this happened, um, and we don’t know what the White House really said in response to that, and then, again, came back and said, “We’re going to register as a foreign agent.” And so the White House was repeatedly warned, and, you know, it’s—anyone—we don’t know. The White House says—it seems—they seem to imply that Trump was not notified of this, that Pence was notified of this, but clearly there was a sense that he knew that this was going to be a big deal and that his legal counsel knew this was going to be a big deal, um, especially in—at the sa—the whole time in the middle, he kept working as the incoming National Security Advisor sitting in on classified briefings, helping the president make national security decisions while they—they had—they were talking about him registering as a foreign agent, so, clearly, you know—it’s not that you just register. Clearly they knew that this was something that was wrong, that it was something that was going to blow up, and, um—and it did.

Engelberg: There are things the government does that are secrets that people don’t know. One thing that everybody inside and outside of the government knows is that if you make a phone call to the embassy in Washington of the Russians it will be recorded, probably, actually, by five or six or seven intelligence services, Chinese, Israelis, Americans, you know, who knows. So the notion that you could, first, make those calls, then deny, in essence, making them, knowing the tapes exist, and then Flynn, remember, is part of the intelligence community back in the day. He was head of the Defense Intelligence Agency. He knows the politics of the intelligence community.

FACTOID: Flynn was director of the Defense Intelligence Agency 2012-2014

You have a president who is just vociferously beating these people up, the people who have the tapes of his phone calls. How in the world—this is not talking about playing chess and getting nine steps ahead on the board. How you couldn’t have thought that that was going to get out and that it wasn’t going to go well, I mean, it just—I’m baffled by it, Vera. I haven’t been as—quite as close to Flynn as you, but how do you explain that?

Bergengruen: Right. I mean, I think that that’s—again, not having him on record saying that, but I think it’s impossible to assume that he didn’t know and that he wouldn’t know, and, you know, there’s a reason that he registered retroactively that, as he was serving as National Security Advisor and paid, um, you know, almost half a million dollars to lobby for these interests, even writing an op-ed in The Hill the day of the election supporting these Turkish interests, for example, things like that, um, and still not having registered as a foreign agent, I mean, there was no disclaimer at the bottom saying, “I’m a lobbyist for Turkey.” That, you know—and we would know that that’s illegal, and he knew that’s illegal, and it doesn’t take a head of intelligence to know that. And like—as you said, just in terms of the interactions, in terms of knowing all these different things were going to get out, that’s—

Engelberg: It just doesn’t make a ton of sense. And then, you have this spectacle of the Justice Department coming to the White House and saying, “He’s vulnerable to blackmail because he has lied publicly about something the Russians know and, by the way, we know, and he should know that we know, so what are we talking about?”

12:36 Blackmon: Well, and, also, I mean, it’s even more specific and more remarkable, uh—is that it’s not just—obviously, General Flynn knew that, uh—that this—should have known that this conversation would be recorded and that there would be concerns about a conversation like this. Obviously, he should have known that. Uh, whether he violated the Logan Act, an act that—or something that’s basically—

Engelberg: Right. [inaudible]

Blackmon: —never been enforced, uh, except once, I’m told, contrary to some reporting, uh, but obviously he should have known those things were problematic.

FACTOID: Logan Act prohibits private citizens negotiating with foreign powers

But then, you have the ac—you have the FBI visit his office and question him about this and inform him of this recording, which by—I don’t think this has been explicitly said. It’s still—technically still classified information, but I think that we know with absolute certainty that he misled the FBI in that—in that conversation, and that is a felony right there. Whether you’re under oath, whether you’ve been mirandized, that’s a felony, and the—and if that’s the case, that somehow, even been informed that there’s a recording of this conversation and, uh—and what exactly was this all about that there is still a denial and that there is still a, uh—an unwillingness to then notify the White House, supposedly, or to try to clean this thing up. So much of this probably was reparable at any number of places along the way, but then you have the acting Attorney General of the United States come to the White House and inform the White House Counsel that these things have happened. Uh, and again, there’s a—I can’t—this is what I’m trying to get at, is that it doesn’t make sense to me either even if you were rooting for this administration. The smartest thing to have done at that point would have been to disclose everything, incinerate Flynn on the spot, and then the White House probably could have extricated itself. So there has to be some explanation for why that didn’t happen, so, as a reporter, part of what we do as reporters is try to think about, “OK, what might be the explanation, and then how do I figure out which ones of these things might be the true one?” What do you go looking for there?

Engelberg: Well, I mean, one thing that comes to mind, when I joined the New York Times Washington Bureau, one of the reporters there was a veteran of the Watergate investigation, and he said to me something that I’ve always kept close to my heart and head. He said, “You know, they always said in Watergate the cover-up is worse than the crime,” and he said, “You know, sometimes the crime is so bad you have to cover it up, and you should not always assume that because people are covering things up they’re stupid. There may be something to cover up that actually is—is quite horrific.” And we don’t know that, but I think as a reporter you have to at least contain multiple hypotheses, and that is certainly one explanation of the behavior we’ve seen.

Bergengruen: And I think we’re dealing with someone in terms—in the president who, um, sometimes seems to act against his own best interests, political interests, someone who wasn’t a political before. And it’s very—to me as a reporter, as we were looking at this, it’s, “Why would he go against his own interests in this case?” You know, he’s—is it because his personality is to be—we know that he’s fiercely loyal to certain people who came out for him early like Flynn did. He likes strong military men. He really likes his generals. He—he really liked seeing Flynn come out on the campaign trail and, you know, speak onstage and, you know, talk about Clinton. And is it just loyalty to that, because he would go above and beyond to—to ask Comey to drop the inve—to do all these different things, um, and to still be talking, you know, trying to communicate with him, trying to communicate with Flynn when everyone is telling him, “It’s a really bad idea. Just—just get him out. Just drop it. You do not want to be tied to him.” Is it just a facet of his personality? He just ha—he feels intense loyalty for this man who went out on a limb for him, or is it something else? And it’s really difficult sometimes to separate that when you’re, um, covering somebody who often doesn't act in the way that we think a rational politician would act. And so—

Engelberg: Now, I have to jump in, though, there. And again, I’m not trying to be a conspiracy theorist here, but you say he’s intensely loyal. Surely, there was nobody more politically valuable at a certain point than Jeff Sessions, and yet we don’t see enormous personal loyalty. That didn’t seem to cut much ice in the end, so I think we have to this day, um, a mystery as to why this would happen, and, you know, Bannon said in a recent interview, “The firing of Comey was one of the greatest political mistakes of all time.” Absolutely true, and yet, frankly, utterly predictable that if you fire the director of the FBI in the midst of an investigation like this, the—there will be calls for a special counsel. And so that was not—anyone who has been in Washington for five minutes—ask Bill Clinton, you know, and then it goes badly.

Bergengruen: And, you know, he—again, not helping his case, saying, “Do—that’s fine. Do what you need. Do not look into my finances,” or, you know, things like that, legal experts I talk to, they say—they keep pointing out that a president is not a normal defendant when these things happen. You know, they—I heard an example recently that was saying, you know, it’s—they’re accusing you of murder, and you say, “No, no, no. I was robbing the house. I was in there, but, you know, I didn’t murder the guy. I just ha—I left before that happened.” Things like that, you know, presidents just—even if it’s something here, then it will be hugely damaging. Something here, it’s even more damaging, and so the—not just—this is not unique to Trump. Previous presidents, you deny everything. You just don’t talk about it. You don’t—you know, it’s easy for us to sit there and say, “Why don’t you just admit if it was this deal, if it was this contact?” And, um, it’s—I think it’s important to realize that a president is not a normal person in a—in a normal trial.

Engelberg: Right. But so, then, where does that leave us? And I think it leaves us in a very strange place because, unlike the Watergate situation where you had a joint committee of Congress examining the events and reporting to the public or even in Iran–Contra where you had things like that, here Mueller’s main job is to identify prosecutable crimes and to bring charges.

FACTOID: Special counsel Robert Mueller investigating Trump-Russia ties

So where are we left as a country if he discovers things that aren’t crimes but are important to the republic, potentially even impeachable? I mean, there’s no sense that I have that he has to report those things. I have—I don’t think—you’re in Washington, Vera. Do you have a sense that these Congressional committees are going to end up doing a thorough report on the events here? (laughs)

Bergengruen: Well, they’re kind of also constricted as to what they’re trying to find, um, and I think that’s what interesting, being a journalist or an investigative journalist. We’re kind of—they’re doing their job, and we’re doing ours, and we’re finding things that they’re not even looking at because that’s not their job to find. And so, I think, sometimes a lot of people are fi—you know, again, looking, let’s say, into his company, into different things. We find things that have nothing—that are still damaging but have no—but that they weren’t even looking at, and—and sometimes they will come out with a little finding, or there will be a leak about something that they’re looking at, and it makes clear a lot of things that we were already looking at for the last two years. So I think it’s—it’s just so broad, and it’s so slow-moving.

19:11 Blackmon: Is it possible that journalists—between Watergate and now, uh—that in the way that Watergate inspired a generation, certainly us, um, in a very direct way to, uh, see the importance of investigative journalism, to see the importance of media as this bulwark against a government that had lied to the people not just during Watergate but during Vietnam and that whole—that huge response, uh, of—of journalists as the protectors of the truth against a government that appeared more corrupt than Americans had previously really wanted to imagine, is it possible that we actually carried it all a bit too far, that we made mountains out of molehills over and over again?

FACTOID: Nixon asserted, “I’m not a crook” during a 1973 media Q&A session

I look at stories that I wrote about city councilmen twenty-five years ago and even some who ultimately went to jail, but, uh—but scandals that I was uncovering working for a local newspaper and such, and I can look back on them now and say, “You know, maybe that actually was a little overheated, and maybe I contributed to the public sense that I can’t trust anybody,” and now, finally, that “can’t trust anybody” is applied to the media as well. Is there any possibility of that?

Bergengruen: I just think—I mean, I think a lot of these stories don’t need that help. We’re—you know, they don’t need to be made molehills because they’re giant. A lot of these things that are happening sometimes, I’m looking at them and trying to put myself in my shoes a year ago, and they’re just so crazy. A lot of these, you know—a lot of what’s happening right now and the biggest stor—it’s the biggest story of our times, and I think, um, yes, I mean, there’s the temptation sometimes to take things that really aren’t that important and over—blow them up. But I do think that a lot of what’s happening in a way, sometimes, I think, is almost being under covered because it’s, um—because we’ve normalized a lot of these things.

Engelberg: Well, as the literal and figurative graybeard on this panel, um, I think you have—I think you have a point, Doug, um, and I don’t know what the answer is to it, because on the one hand some of the things over the years that have become -gates, Travelgate or whatever, you know—things no one even remembers—that was during the Clinton years. They hardly merited a -gate, and I think we did on some level, in our aggressive pursuit of—of wrongdoing by public figures and companies, uh, you know, lower the public’s trust in some of these institutions. On the other hand—and I think back on it—a lot of the things that we held accountable really needed to be held accountable, and, you know, I think this is kind of an inevitable process where you, um, have a press corps that’s going to dig into things. Um, and some of them are going to turn out to have been bigger deals than others, um, but I think the alternative, which is to say, “OK, let’s not write so many negative stories,” um, you end up with Bell, California, which was a small community, um, about an hour from the LA Times newsroom that nobody covered and had a city council that had quiet meetings that were attended by nobody and voted themselves $900,000-a-year salaries, um, and eventually the LA Times exposed this and won a Pulitzer Prize, as they should have. So, I mean, I think, you know, between too much scrutiny and too little scrutiny, I will take, you know, more rather than less, but I think we have to acknowledge that, yes, this does harm the public’s basic faith that anybody is telling the truth about anything. And has it come back to hit us? Yes, it has.

22:26 Blackmon: Yeah. Well, I’ve long called myself an apocalyptic optimist. I was saying this back when the fear was TV, and nobody had even heard of the internet, but that this giant transformation, this apocalypse, was coming, which—it has come, particularly for anybody who made a career in the newspaper business. The apocalypse came, but I’ve been an apocalyptic optimist in the sense that I do still have the faith that on the other side of the moonscape of the apocalypse the—there is this unpredictable world with lots of little things blossoming, like Buzzfeed, um, and—(laughter) uh, and hopefully that will all work in a way, uh, that it serves our democracy in the way that we need it.

Engelberg: Right. I mean, in this period, I would—I would add that ProPublica has gotten record amounts of money contributed. And to me, the most touching is not the foundations and so on, although that’s wonderful and important support. It’s the people who write in and say, “I’m out of work. I’m sending you $40. It’s all I’ve got. Please, you know, keep our democracy going.” And we have lots and lots of people who write notes like that. Um, and I guess I still get up every morning and believe that providing factual information in the long run, um, will, you know, keep our democracy where it needs to be.

23:33 Blackmon: Vera, do younger Americans see someone like you, uh, and say, “OK,” because you’re a little closer in age to whoever this imaginary person is, um, do they look at you and say, “OK, you’re—this is a really serious person but who is kind of like me, I think, and is operating in this new realm of media that I’m a little more comfortable with?” Do you feel, uh, you know—a particular burden of any sort that comes with that? And by that, I mean, that’s not a bad burden, but, I mean, do you think that—do you sort of owe something to them, or is that out there? Is that—

Bergengruen: I think there—it is kind of out there. You know, a lot of—I mean, I—especially among young people, there was this kind of, you know—I had a lot of friends and a lot of just people I know who all were saying, “I—I’m subscribing for the first time. I would rather pay for Netflix, but I’m going to pay for the New York Times. I’m going to pay for the Washington Post.” Um, you know, a lot of people took pride in that. They—they’re realizing the importance of—of journalism, but I think there also is a sense that, you know, this—the generation that they trust is leaving, and people my age, you know, we are—we’re enter—we’re working in this different environment where we’re not go—you know, they see—they look at Watergate. They look at all these different things and, um, this generation that—that did all this kind of reporting, and I think it’s, uh—given the environment that people like me are operating in, I think, sometimes it’s a bit of, “OK, let’s make sure we’re learning from the best and can kind of keep doing that kind of work,” because otherwise everyone is still operating in their own little sphere. But I do see—there’s a huge interest in—in that, and I think it says a lot that they think that it’s only the press keeping them from, you know, not knowing what’s going on.

25:05 Blackmon: Well you’ve given me a lot of confidence. I’m glad to see you out there. Vera Bergengruen, Stephen Engelberg, Thanks for being here. We hope you’ll join our ongoing conversations about the presidency, the major issues that face the nation, and how to restore civility and an appreciation of history, and just simple decency, to the way we all engage in democracy. To watch this and other episodes of American Forum, read transcripts or find other resources, go to our website or Miller Center Facebook page. And of course, keep watching on your local PBS station. If you have a question or comment, you can reach me on Twitter @douglasblackmon. You can find our guests on Twitter at @SteveEngelberg, and Vera Bergengruen is @VeraMBergen see you next week.