About this episode

December 27, 2017

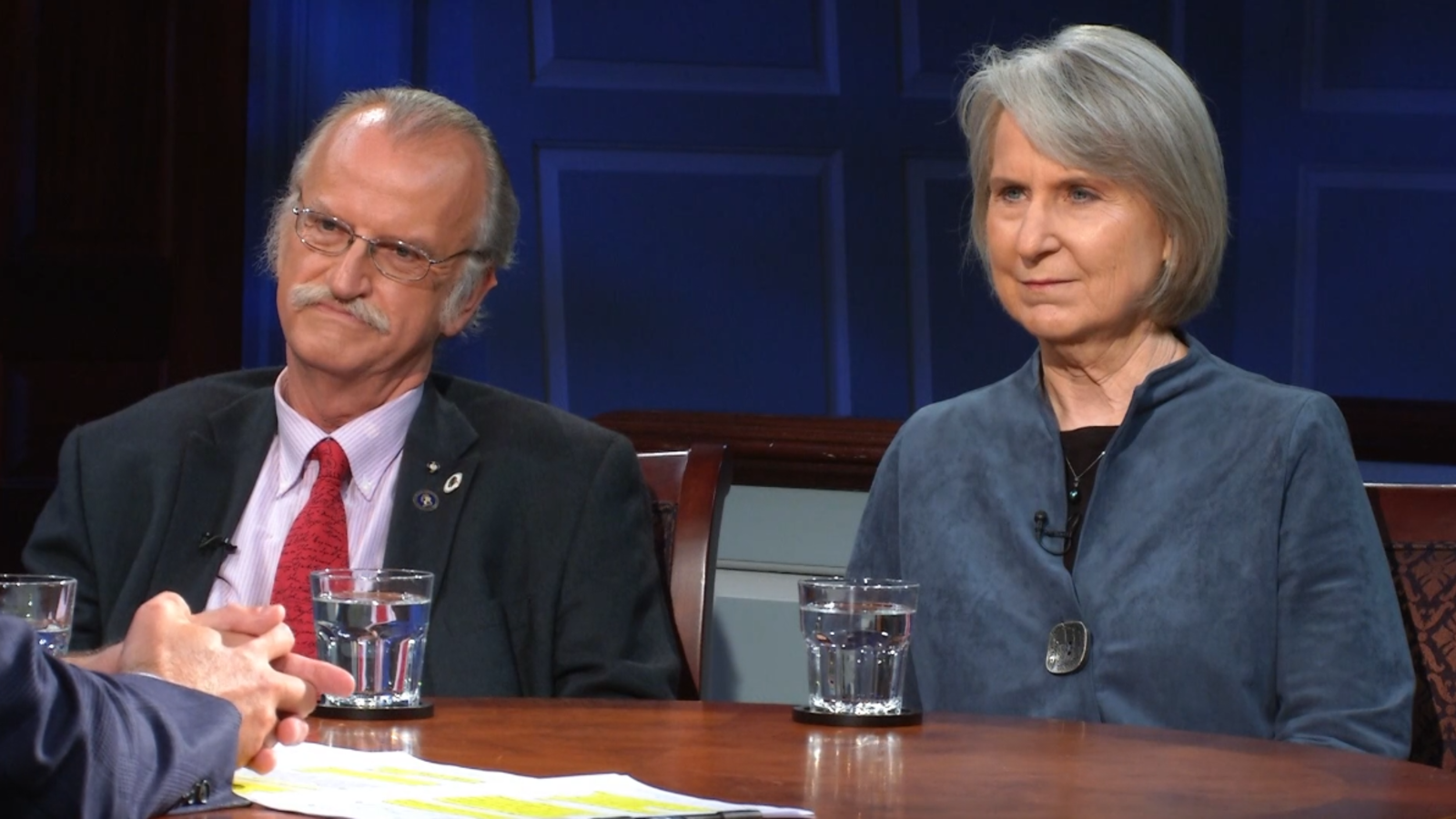

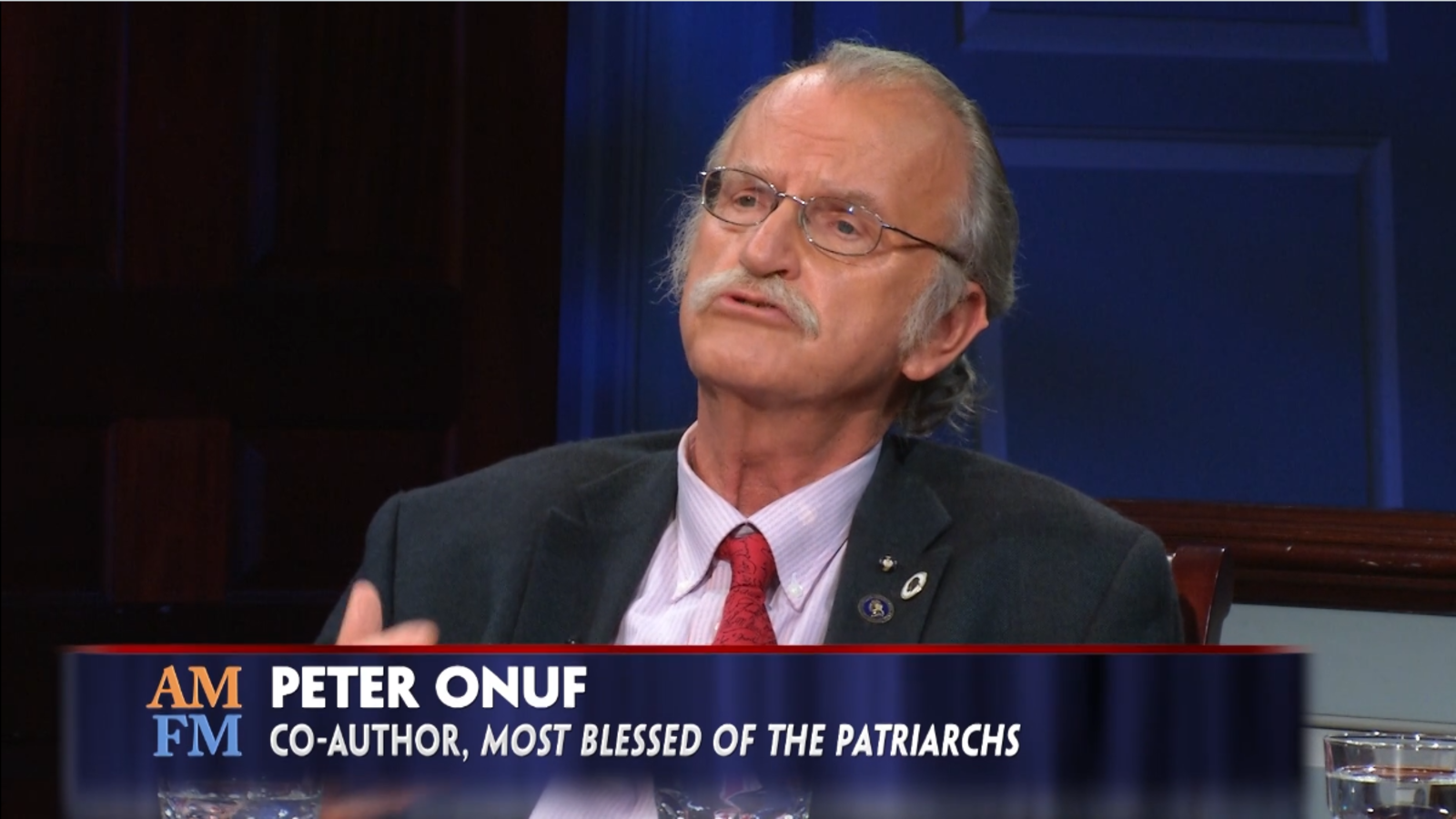

Kathleen Flake and Peter Onuf

Hosted by Douglas Blackmon

Religion

Why do we believe in religious freedom?

Transcript

00:40 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. There is no more bedrock American ideal than the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted with the original Bill of Rights in 1791, guaranteeing that the government could make no law respecting establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise. Those words established unequivocally the cornerstone importance of religious freedom in the United States and also elevated to the forefront of American beliefs the importance of a free and independent press and the rights of citizens to believe, in effect, whatever they wanted about faith, politics, science, and, today, even what constitutes a fact. Ironically, in some respects, freedom of religion and expression became our national faith. All of that unrestricted liberty to think and share views as we wish was anchored in the notion of religious freedom and largely drawn from the Virginia statute for religious freedom enacted five years before the First Amendment and drafted by Thomas Jefferson, who, of course, was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence and our third president. Jefferson’s statue said, “All men shall be free to profess their opinions in matters of religion,” and that a person’s faith could not be used to limit or to enlarge his power or position in public life.

But, more than two centuries later, have we failed to protect Jefferson’s sacred standard? Mormons were ostracized westward in the nineteenth century and ultimately engaged in an armed conflict with the US Army in the 1850s. Native American religious beliefs were murderously suppressed. Anti-Semitic rhetoric flourished in the early- to mid-twentieth century. Anti-Catholic sentiment threatened John F. Kennedy’s presidential candidacy, and fights over religious freedom continue today. Residents of liberal New York City blocked plans for the construction of a mosque in Lower Manhattan after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Christian groups opposed to abortion have challenged the Affordable Care Act, saying its mandate for contraception compels some company owners to violate their religious faith. All across the country, conservative politicians raise money and energize supporters with unfounded claims that Muslim Sharia law is being adopted and that any germ of Islamic influence must be stopped. During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump called for a complete shutdown on Muslims entering the country. As president, he signed an executive order—the so-called Muslim travel ban—that the Fourth US Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, “Dripped with religious intolerance, animus, and discrimination.” And then, neo-Nazi nut jobs marched through this city where we’re taping this program, Charlottesville, Virginia, chanting threats against Jews and claiming they embody the true values of Jefferson and the founders of our republic.

So is religious freedom truly a fundamental American belief, and can it survive as Americans grapple with an ever-increasing plurality of religious faiths and ethnic backgrounds? What would Mr. Jefferson say? Joining us to explore these questions are two scholars from the University of Virginia. Peter Onuf is an emeritus professor of American History and the author of many books exploring the life and beliefs of Thomas Jefferson. Kathleen Flake is a professor of Mormon studies and an historian of Christianity in America. Thank you both for being here.

Peter Onuf: Glad to be here, Doug.

Kathleen Flake: A pleasure.

4:06 Blackmon: So what did religious freedom represent to Thomas Jefferson and the founders? And before you answer that, put it in the context of—that in 1790, I think, there were maybe four million people in America, roughly. What did religious freedom mean then?

Onuf: Well, Doug, it’s important to remember that Christians had a genius for slaughtering each other for centuries, so it’s not as if these are innocuous differences as we might think in the retrospect of the 1950s, “Go to the church of your choice,” when it didn’t seem to matter at all. What Jefferson had on his mind is that, historically, in the recent experience of Anglo-Americans and independent Americans, religion had loomed large as a reason for going to war, and more seriously or important in his own time was the concern that a church establishment was the foundation for tyrannical rule, the old regime. He contrasted new world and old. The old world, the people in the old world were subjected to the tyranny of monarchy, aristocracy, and priestcraft, organized religion. We think of faith as something that deeply expresses who we are, and it’s very important to us because this is a fundamental. Yet, in Jefferson’s time, religion seemed to be a tool of the state leading to what you might call a kind of false consciousness when people were forced to conform to a particular set of religious practices and beliefs that supported the state. And the big challenge for Jefferson was to make sure that the republican government that the Americans were establishing would survive, and that was predicated on freedom of conscience.

FACTOID: Jefferson: “Question with boldness even the existence of a God”

06:03Blackmon: So Jefferson clearly had these very specific concerns about faith, but among the broader understanding of that at the time and the other Founding Fathers, did they share that same view, or was it as much that as it was independence of thought and the other kinds of freedom of expression that the First Amendment also—what did the founders care the most about in that context?

Flake: Well, I think they would have been as diverse in their thoughts about that as the ideas that abounded in the new republic, this early republic that they were designing, but I think the one thing they would have agreed on across the spectrum, whether they came at it as conserv—what we would call conservatively religious, they had devotional commitments that wanted freedom, or whether they had intellectual commitments that demanded that individual conscience be respected and the more Enlightenment, deist voices. They both agreed that the independence of the conscience was necessary, and they wanted freedom from government control. The complexity arises that they wanted it for different reasons, so the evangelicals would have wanted freedom in order to be more religious, specifically religious, devotional religious, and Jefferson would have wanted freedom not so much for that devotional liberty but for that freedom of conscience that was inalienable, right? Not just rights inalienable, but it was human nature to be free. God hath made the mind free, and the god he had in mind was God, nature. I am free, and my mind is free. And if you oppress my mind or restrain my mind or demand my mind think a particularly way, then you are engaging in tyranny per se, either that or you’re hypocritical.

Onuf: Look at Massachusetts. Jefferson is considered a kind of Unitarian. He was an anti-Trinitarian. Well, John Adams was also a liberal Christian and progressive in his thought, but he said, under the Massachusetts constitution of 1780, which he authored, there is a freedom of conscience clause, but there’s also an establishment clause.

FACTOID: 1780 Massachusetts constitution allowed state support for religious teaching

Massachusetts needed an established church because the people needed ethical grounding. It wasn’t that they had to believe a certain—profess a certain faith, but they certainly needed to hear the good word about the way they should behave, the ethics, the practical ethics. So this anxiety about republicanism, it’s the obverse of Jefferson’s concern for the absolute freedom of the mind, and then pair that with—the counterpoint to that is anxiety about the ability of people to do the right thing, to access that—the teachings of conscience or ethics. They weren’t—there was great fear of democracy, so those two things are in tension with each other.

09:01 Blackmon: It’s in some respects an inherent conflict between the basic Enlightenment idea that there is something fundamentally good about man, that the nature of man is toward good, but, at the same time, this concern that maybe there is not.

Onuf: But “toward” is the operative word, because “not good yet” necessarily.

Blackmon: Yeah.

Onuf: That’s a work in progress. That’s why all the founders, Jefferson included, were obsessed with education, popular education. How are you going to achieve this level of enlightenment? How do you look beyond yourself? Another way to put it is, “How do you achieve a level of good citizenship?” These were people who had been subjects of George III, and now they’re expected to be making key decisions that are going to affect not only their own lives but their children’s future. That’s a lot to ask of a people.

Flake: What did they think religion was. That’s where this gets interesting historically. There is an exchange between Adams and Jefferson where Adams is describing for Jefferson what it was like to achieve unanimity among such a diversity of representatives from the various colonies or states, depending on the stage and what they were doing. But he says, “What could we agree on?” notwithstanding that we had Catholics and Jews and Protestants of all kinds, house Protestants and horse Protestants—

Blackmon: Yes. (laughs)

Flake: —meaning evangelicals or the standing churches. He said, “What could these beautiful young men agree on?” And he said the basic principles of British—of liberty, of British liberty, and general Christianity, the general principles of Christianity. That’s what they thought they were protecting, and the general principles of Christianity as nearly as I can tell—and I don’t know if Peter would agree with this—was a moral order.

FACTOID: Jefferson wrote Jesus’s teachings “most sublime” system of morality

Onuf: Sure.

Flake: It was ethics. It was morality. And they were all to a person, I think, opposed to superstition, and superstition was, for example, sacramentality of the Catholics. It was a particular kind of action around religion, so very—they’re able to come in and feel very copacetic about establishing freedom because they think religion is essentially what happens in your head. It is your conscience. It is your belief. It’s not necessarily what you do, though, of course, they would have wanted worship, but worship for the sense of moral order in the state.

11:16Blackmon: All rights, all fundamental rights, in fact, have limitations, yet we have a desire for oftentimes—Americans have a desire to believe that these rights are, in fact, absolute even though the Second Amendment, the right to guns, which—in fact, many Americans want to believe that’s an absolute, unrestricted—

Flake: Nonnegotiable.

Blackmon: —nonnegotiable thing, and yet, in reality, we have all kinds of existing limitations to those rights, and some would argue there should be more. So this conflict between our fantasy for absolute rights—but the idea, though, that in Mormons you see something that I think we see in modern times—I’m curious to see how you relate to this because—and this is back to what Peter was saying from the very beginning, that—I think we seem to have this much higher tolerance of a diversity of faith when, in fact, it doesn’t particularly challenge some of—or become too complicated in terms of these questions around limitations on rights.

FACTOID: Book of Mormon published 1830, services begin near Fayette, NY

But when it becomes what looks like an existential threat, as Mormonism perhaps did in its differentness, its own military, the fact that the political leaders and the religious leaders were one and the same, all of these things which seemed so foreign. So, now, when we have these discussions about Sharia law and this mostly made-up notion that Muslims in the US somehow will be under the—will be forced to follow the edicts of their faith over the—that, really, they’re not American because ultimately they’re just Muslims and that Islam says to execute the infidels. And so, ultimately, this is a faith we can’t trust, even though Thomas Jefferson said he did back at the beginning.

Flake: No, this gets crazy-making because that allegation about Sharia law is based on the assumption that the religious liberty right is absolute, and, therefore, it’s going to be wreaked on us, so we want an absolute right so we can wreak it on them.

Blackmon: Exactly. It’s this crazy circle.

Onuf: Yeah, [inaudible] absolutism is—right.

Flake: So it gets crazy-making. Yeah, it’s crazy. We don’t think well on this subject, and it’s not just our passion. We, I think, haven’t really reflected sufficiently and trained our citizens in ways to think about the limitation. All rights have limits. All rights have limits, and to live in a democracy it is constantly a negotiation about human behavior and human rights, a constant negotiation. No matter what the right is, it’s all being negotiated all the time.

Onuf: And those rights have to be set in their historic context. When we make them absolute, we take them out of those contexts, and we assume they’re context-less and don’t depend on context.

Flake: Well, I think when we claim absolute legitimacy in the Constitution we’re making that move. Yeah.

Onuf: Well, I want to pick up on what Kathleen said about polygamy and the way it threatened the moral order of antebellum United States. It’s one of the twin pillars of barbarism according to the Republican presidential platform. Jefferson believed that family values were very important, that the nuclear family as we understand it was foundational to his conception of the republic. Well, what has happened to the family form, and does our republic really depend on a nation of yeoman farmers who are independent and capable of consent, or have things changed? And when we hang onto these ideas of the ideal American society or the original intention and original context of the farmers and their celebration of family values, have we not changed? Do we need to take stock of that? Does that form govern us into the future? That’s—those family units are predicated on the idea of the household economy, which is the way the world runs in this period.

Flake: But I think the larger point there is that people who want to look at the constitutional level as if that is the ultimate and positivist statement of what is and is not possible are really arguing against the moral shifts in the nation.

Onuf: Sure.

Flake: Right? And those are unavoidable. Society is going to change, and this is back to Jefferson, too, with his famous belief—

FACTOID: Jefferson believed the Constitution should be rewritten every 19 years

Onuf: And he knew it.

Flake: —that it’s for the living, right?

Onuf: “The earth belongs to the living.”

Flake: The earth belongs—so every nineteen years the new generation steps up, and they get to say what’s right or wrong, which is—they get to say what the law is. So those people who are making a claim about some—who are, we would say, reifying the Constitution, making it a thing that is absolutely transparent—we can understand it, and we just need to apply it for gener—are denying that the force of the law comes from the moral order of the people as divined by judges and by the representatives. So laws are going to change in response to what people want, and we as Americans need to figure out what we want on this, and we need to unders—we need to decide whether it’s going to be winner-takes-all or whether we’re going to find some kind of compromise in the variety of moral orders that exist in the United States.

Onuf: Well, I hope compromise, because the problem with your formulation—it’s not your problem. It’s the formulation. Who is “we”? And then, of course, you, as you explicated—

Flake: Well, but—

Onuf: —that is a game in which there is a winner and a loser.

Flake: This is—but the “we” in a democracy is the majority unless there’s a right that restrains the majority.

Onuf: I don’t know. (laughs)

Flake: Unless there’s a right that restrains the majority. Some rights are nonnegotiable. You get to vote. You don’t—majorities don’t get to choose that unless there’s gerrymandering, (laughter) but those are political problems. So what about religion—I guess there are people who want to say that we cannot negotiate with religion, and I think we can. I think Mormons are an example, and the example is on gay marriage. Mormons have negotiated on gay marriage. Utah was the first state to say, “We respect your right to be free of discrimination in housing,” right, “and in employment, but we want to keep marriage over here.” Well, they lost on that one. When the court came out and said, “Marriage is now not—gay marriage is not going to be negotiable anymore on this; we’re going to say that’s a right,” then the Mormons say, “OK, we recognize that right, and we’re going to regulate on the inside, but we will recognize the law on the outside. Religions can do this. Religions can negotiate with the state.

Blackmon: And so—

Onuf: And religion is not fixed, either, Doug. Of course, faith commitments change and evolve over time.

Blackmon: Mormonism wasn’t fixed either. Yeah, exactly.

Flake: Right, so—I don’t know. What are we trying to say here? To me, two kinds of problems that we see in the current environment that the Constit—that the founders don’t really help us much on, one is this idea that religion is practice, that it’s not just what we think, and therefore it’s brought within the ambit, within the scope of proper regulatory authority. People have to decide how they want to handle—what kind of power do they want to give the state to control religion, and this is the question of—“Religion is just an excuse to discriminate” is a very popular phrase today. What kind of exemptions are you going to allow for religious conscience over and against other kinds of human dignity, right?

18:37 Blackmon: Such as contraception under the Affordable Care Act being an example of that tension.

Flake: Right.

Blackmon: But let—but let me ask you, though—if we try to imagine—I know these are the sorts of things that historians absolutely hate to be asked, generally speaking, but if we try to imagine some version of Thomas Jefferson evolving in some—if you try to make some predictable sense of who this person—if this mind had existed, continued to exist, over the last 200 years, is the challenge of the—the challenge of Mormonism or the challenge of these tiny minority things that he was faintly aware of actually becoming at least meaningfully large communities in an American nation that he could never have imagined with 327 million people—but if somehow the mind of Thomas Jefferson had seen all of this, would he think that the oppression of Mormons was a reasonable defense of the state, or would he, if we were—today, would he say that if the current president believes that a certain group of people of a certain faith represent a threat to the United States it’s reasonable to ban them from this country? Where would he have come down, do you imagine?

Onuf: Well, I would suggest that Jefferson’s first concern would be to sustain the unity of the people. What that means in fact and what the people is, that’s always been a contingent, negotiated question, and I like to think that Jefferson would be a good historian, that he would appreciate the process, that that idea of a new Constitution every nineteen years is a way of recognizing or acknowledging the need to change the Constitution, to change the regulatory apparatus, to adapt to these differences. And, yes, I think he would applaud the ability of this people to continue to think of itself and act as a people in the recognition of their diversity. We don’t all have to look the same. He has various statements along those lines. In his own time, given his own assumptions about the way the social order works, the moral order, he would be dumbfounded, confounded by the way we live now, but would he say, “You have to stay with this regime that we created and this document?” No, absolutely not. The only way we can ever enjoy rights at all is if we are a people. We have a civic identity. We recognize each other’s rights, and what those rights are and how we recognize them, that’s always going to be a work in progress. Jefferson knew that. He would like to think that the arc of our history would be progressive toward a higher level of moral development. It’s hard to say that that’s the case, but he would be with us in hoping that we could reach some higher level. The predicate of reaching any level is to stay together.

Flake: I think Mormonism would have tested Jefferson not unlike slavery, and I think he would have failed the test as he did with slavery. I think he most—he believed that government which governs best does so locally. Once Mormonism got a jurisdiction, you know, Mormonism was run out of the United States by states with state power, and the Mormons said, “We want one of those. If that’s—we want one of those.

FACTOID: Missouri “Extermination Order” in 1838 violently expelled Mormons

If that’s what we need in order to practice our—we want a—” so they went and got themselves a state. I think at that moment Jefferson—that would have tested Jefferson, and—

22:17 Blackmon: But now, fast-forward into the present, which are somewhat different—Muslims in the United States don’t have a state, don’t have anywhere near the possibility of a state, are not in fact trying to impose Sharia law. It’s a frighten—to some people, it’s a frightening invention that this could be happening.

FACTOID: 2011: 30% of U.S. believes Muslim citizens want to enact Sharia Law

But, nonetheless, there are many Muslims outside the United States—by no means the majority of them, but there are some—in fact, they are defilers. As so many Muslims say, they’re defilers of the faith. They’re apostates in their own way, but they’re—so here we have the—we confront in modern times where we have—in recent years, we have seen in the immediate aftermath of the most humiliating attack on the United States since Pearl Harbor that we have a president who is not viewed as a particularly intellectual or brainiac kind of president, but we have President George Bush who comes out and says, “We’re going to strike back against these enemies of America, but this is not a war on Islam,” in fact, maybe his highest moment in terms of a statement of American principle. And now, we have a president who says, “No, the reality is that we are, in effect, engaged in a war against not just some individuals who have run afoul of their faith but their faith, that faith itself. We have to exclude them from the country for straightforward existential reasons. And it may be a little messy, but it’s necessary to safeguard the union, the unity of the people.” Where do we put Jefferson? Where would you put Jefferson in that balance?

Flake: I think Jefferson would have looked at the facts before he made his decision, in which case he would not have banned people based on their religion. I think there’s just—I think there’s no way I could imagine Jefferson supporting the kinds of politics we’re seeing today with respect to Islam. I think he would have seen this as hysteria and would have hoped reason would eventually reign, as we do all.

FACTOID: Trump called for a “shutdown of Muslims entering the U.S.” in 201524:08

Blackmon: Hysteria, the thing that perhaps he feared more than almost anything else in democracy.

Onuf: I think that’s right. A failed state is going to exercise coercive power in the most violent and lawless ways. If the United States becomes a failed state because we are so bitterly divided and polarize, then all of the things that the founders feared about the imminence of anarchy, the loss of their rights, the loss of liberty would come to pass. I think Jefferson, though he was optimistic—and we’ve talked about his naïveté—also had a darker side, a recognition that it could all fail. And certainly, slavery precipitated dark thoughts for Jefferson, and that is in the Missouri Controversy.

FACTOID: Jefferson: Missouri Comprise could be an “act of suicide” for U.S.

Flake: Well, that—but they all thought the democracy was fragile.

Onuf: Oh, yes.

Flake: So I think—Jefferson, I think, tells us what he would think of our day when he says, “If you attempt to coerce the conscience,” he says, “then you either become a tyrant or a hypocrite,” and we certainly hear that word, “tyranny,” tossed around today.

25:02 Blackmon: I think that’s where we should stop. Thank you very much for our journey into the mind of Thomas Jefferson and the mind we imagine might have been, but thank you very much for being here.

Onuf: Thank you, Doug.

Flake: Thank you.

Blackmon: To view past episodes of American Forum or to read expert insights into the most pressing policy issues of the day, visit our website at MillerCenter.org, and don’t forget that you can watch live tapings of this show at the Miller Center Facebook page. If you have any questions about this or other episodes and you’d like to read a transcript, reach out to me via email or on Twitter, @douglasblackmon. See you next week.

.