The Continuing Necessity for Bipartisanship

Bipartisan support is indispensable for lawmaking

I know you’re one of the ones who thinks it’s naïve to think we have to work together. But the fact of the matter is, if we can’t get a consensus, nothing happens except the abuse of power by the executive. Zero.1

—Joe Biden to MSNBC’s Joy Reid, Democratic presidential primary candidate forum, 2019

During the 2019 primary race, candidate Joe Biden wanted Democrats to understand that advancing the party’s policy goals required bipartisanship. Drawing on his long Washington experience, he said, “If we can’t get a consensus, nothing happens except the abuse of power by the executive.” As president, Biden has secured some major bipartisan legislation, including on infrastructure, veterans’ health care, and semiconductor manufacturing. Nevertheless, Biden—like other recent presidents—has discovered that winning bipartisan agreement on his campaign promises is frequently impossible. Many of his agenda priorities—including voting rights, childcare, universal prekindergarten, immigration, campaign finance, and police reform—have bogged down in partisan disagreement. In such an environment, Biden has found himself drawn toward unilateral approaches he disfavored as a candidate, repeatedly acting unilaterally only to be struck down by the courts. This pattern is characteristic of contemporary presidents.

Two (related) trends consistently weaken presidents in the polarized era: stronger partisanship in the mass public and geographic polarization. The public’s strong partisanship puts a firm, low ceiling on presidents’ job approval. Geographic polarization tends to confine presidents’ base of support to either red or blue states. Their narrow political bases afford recent presidents little leverage in dealing with the opposition party in Congress. Recent presidents’ political weakness tempts them to use their unilateral authority. When unilateral actions are blocked or overturned in the courts—as they often are—presidents pass the buck of responsibility for failure to other actors.

Bipartisanship Remains Indispensable

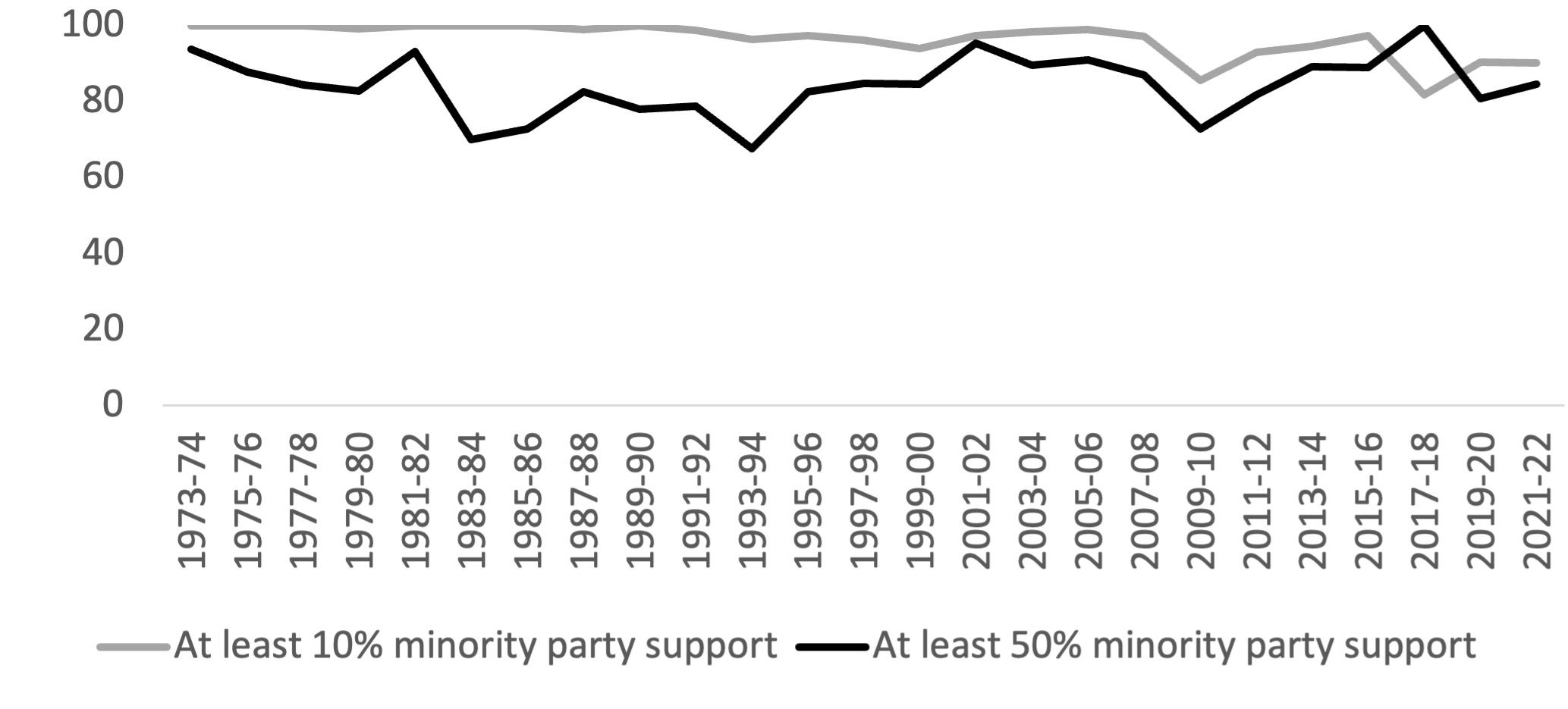

Candidate Biden was right in observing that little happens in Congress without bipartisan consensus. Even in today’s partisan era, laws rarely get enacted on the strength of just one party’s support. In fact, enacted laws are almost as bipartisan as they were a half-century ago, as shown in figure 1. More than 80 percent of the laws enacted since 2012 passed Congress with majorities of both parties voting yes, meaning that these laws were strongly bipartisan. More than 90 percent of post-2012 laws had the support of at least 10 percent of minority-party members in Congress, meaning that these laws were bipartisan in more than token fashion.2

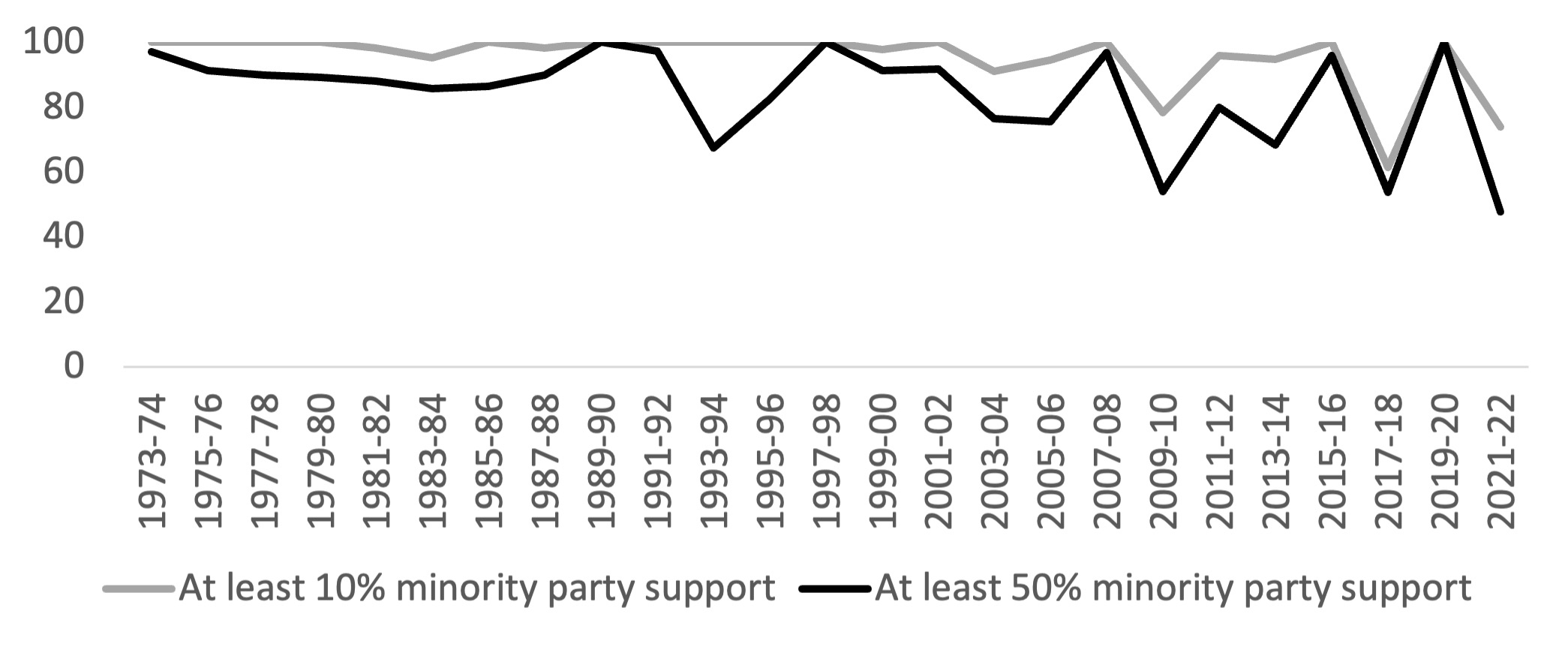

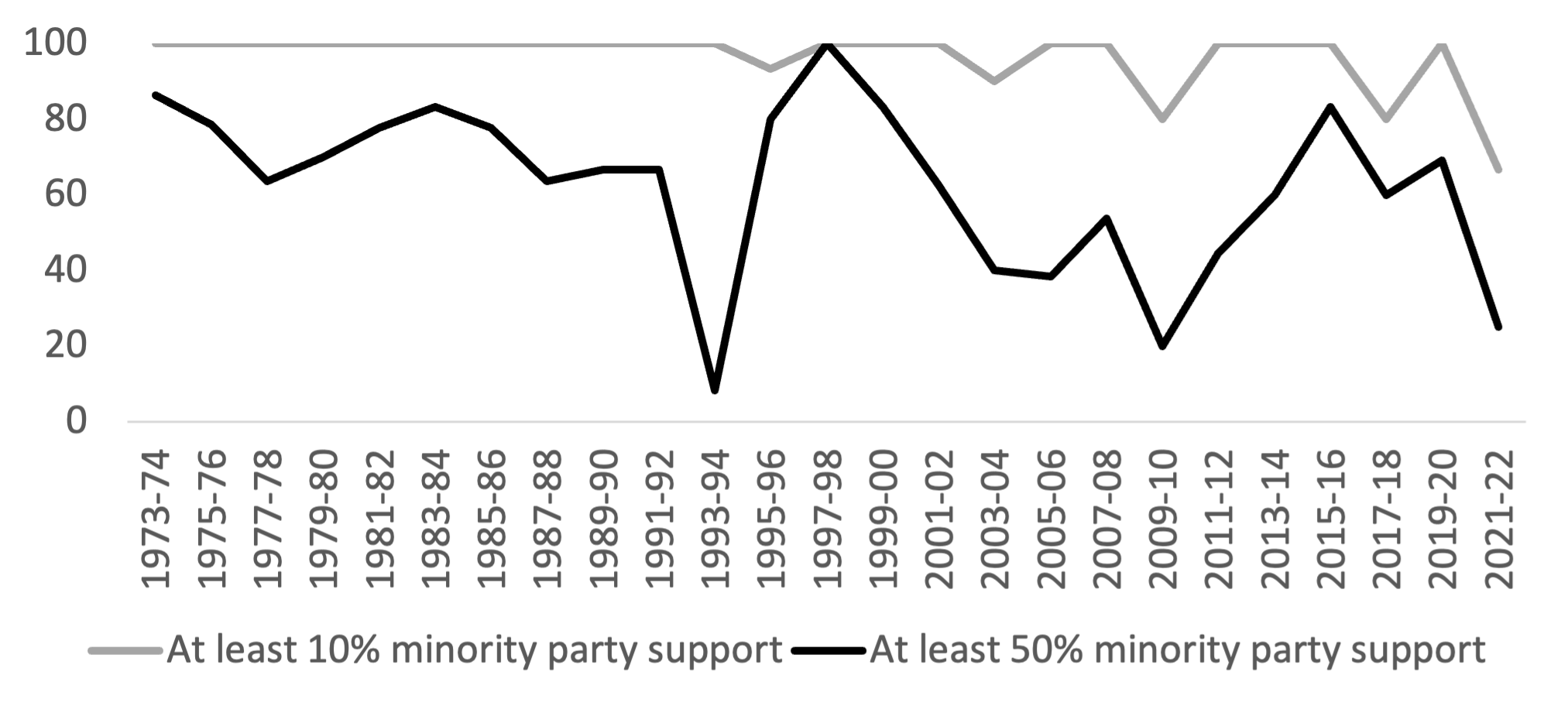

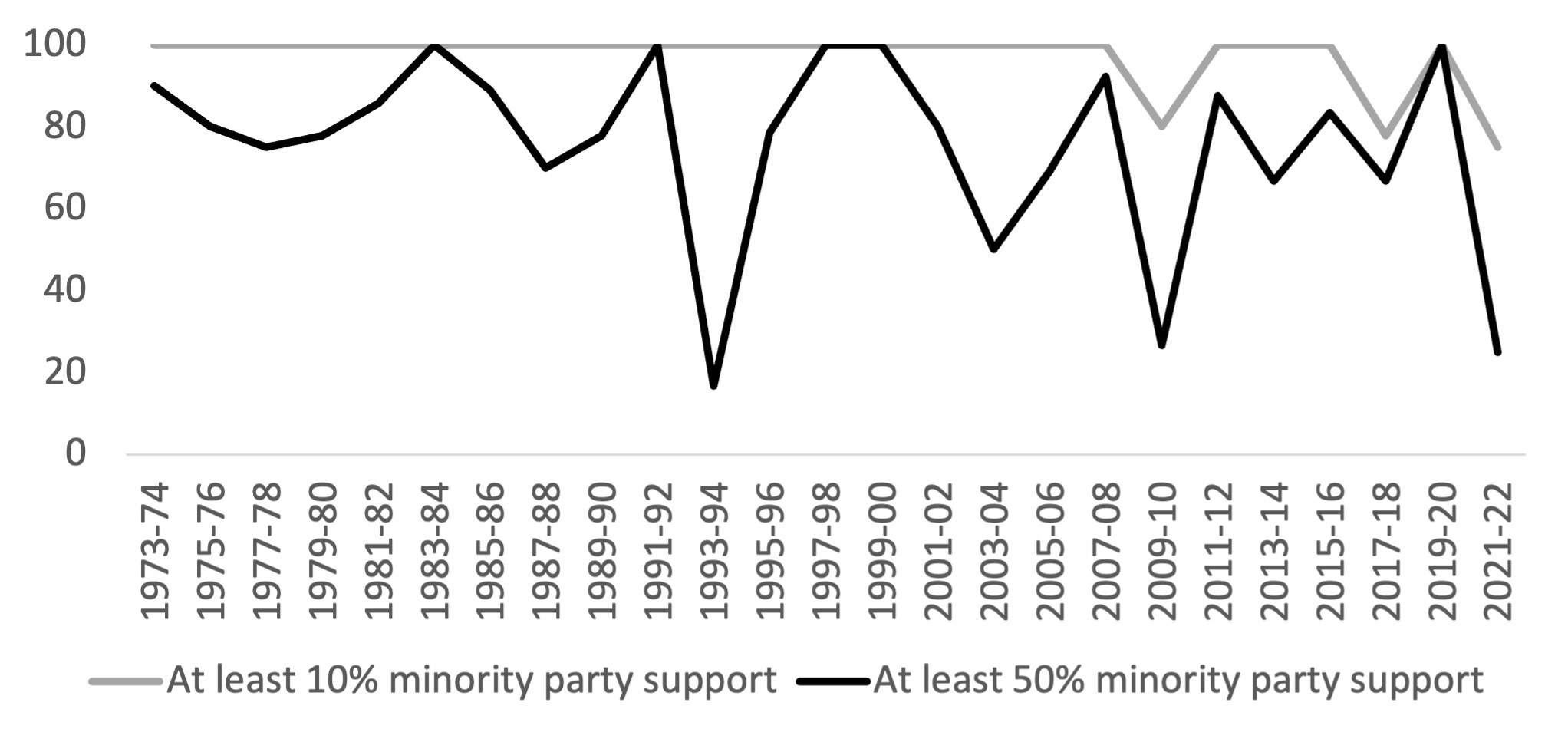

Bipartisanship extends far beyond minor and routine legislation. Major laws are also almost always substantially bipartisan. Figure 2 displays these bipartisanship statistics just for the handful of important laws enacted by each Congress.3 Although a few important laws have passed on party-line votes across recent decades—for example, the Bush tax cuts, Obamacare, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the American Rescue Plan—such laws are highly unrepresentative of Washington policymaking, even in the polarized era. Across the past decade, an outright majority of the minority party voted for 64 percent of the important laws that were enacted. At least 10 percent of the minority party voted in favor of fully 90 percent of important laws enacted since 2012.

As evident in figures 1 and 2, bipartisanship tends to dip under conditions of unified party control, but there is no overall trend toward reduced bipartisanship on lawmaking. Despite the long-term rise in party polarization, Congress still rarely passes laws on party-line votes. The continuous need for bipartisanship to successfully pass laws is perhaps the single most important fact about Congress’s role in the American political system under today’s conditions.

The enduring imperative for bipartisanship stems from three roots. First, divided government is the normal state of affairs in our closely competitive party system, with different parties controlling Congress and the presidency three-quarters of the time since 1980. In divided government, Republicans and Democrats must cooperate to achieve any legislative success. Second, the Senate filibuster obstructs the majority party from passing legislation for which it cannot win significant bipartisan support. Third, even when presidents have unified party control, they usually possess only slim majorities in Congress. Narrow majorities often cannot find perfect consensus on controversial issues. Consequently, recent presidents have failed spectacularly on top agenda items because of a lack of intraparty cohesion. The collapse of Biden’s Build Back Better plan and Donald Trump’s drive to repeal and replace Obamacare offer two recent examples. Given these three factors, bipartisan support is almost always indispensable for lawmaking.

Recent Presidents’ Narrow Base of Support

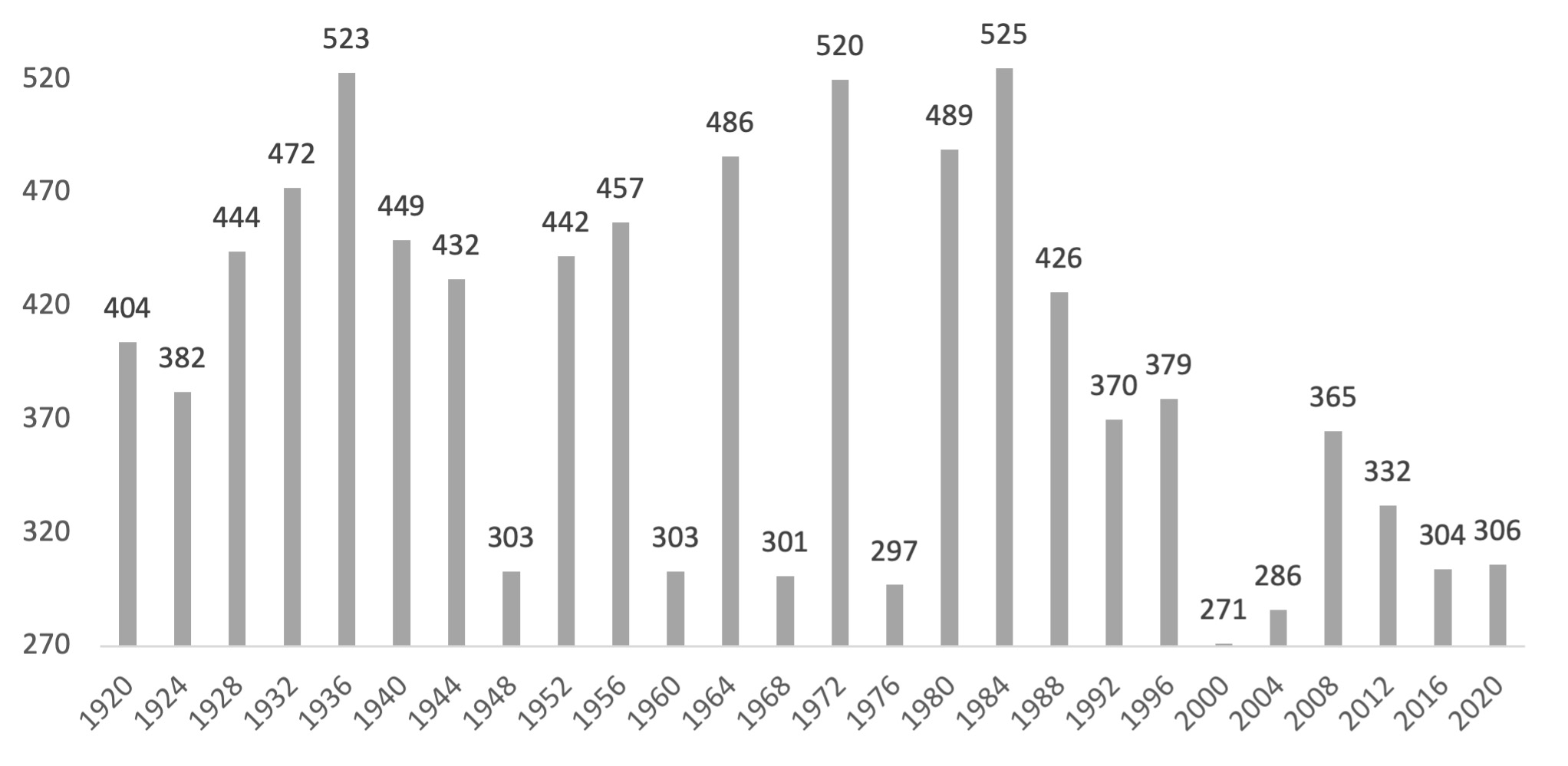

Presidents cannot evade the need for legislative bipartisanship regardless of which party controls Congress. However, recent presidents’ narrow electoral coalitions afford little incentive for the opposing party to collaborate. There has not been a presidential landslide since 1984 (fig. 3). In contrast, presidents during the 20th century normally entered office after racking up big Electoral College victories and winning majorities in most states. Presidents since Bill Clinton entered office with smaller Electoral College majorities and weaker, more geographically limited coalitions. The rigid, post-2000 map of blue and red states means that successful presidential candidates carry the states aligned with their own party but very few states aligned with the opposition. Presidential elections get decided in a handful of swing states.

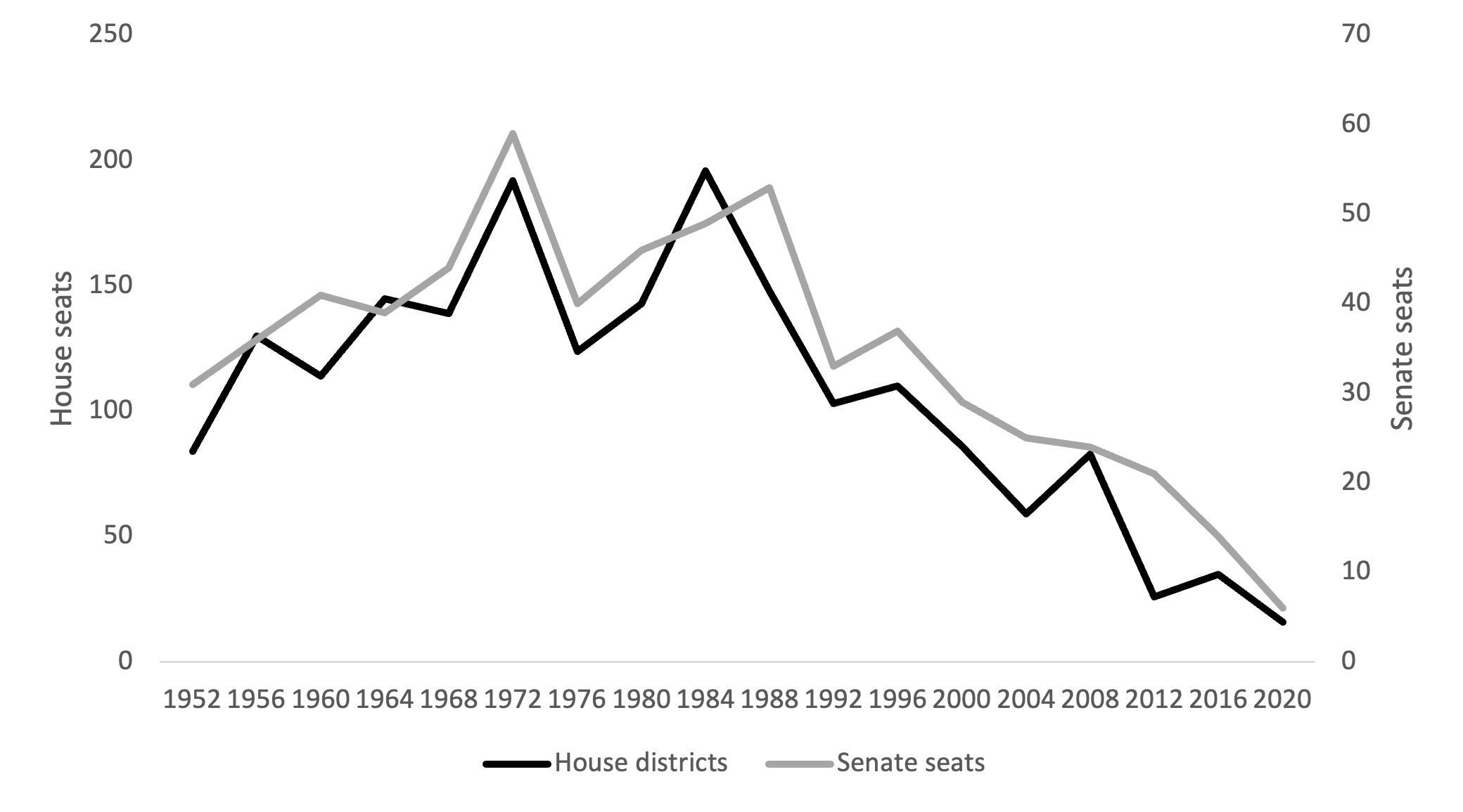

Viewed from Congress, the rigidity of the red-blue map means that presidents garner majority support in few, if any, states and districts represented by the opposing party. As shown in figure 4, the number of split outcomes in congressional and presidential elections has fallen to historic lows. Biden, for example, won office while carrying the constituencies of only 14 Republican House members and 2 Republican senators.4 Presidents’ failure to successfully attract such constituencies stiffens the opposition they face.

Presidents in the polarized, post-Clinton era have not conducted themselves so as to win over opposing partisans. Indeed, each successive president seems to plumb new depths of disapproval among the ranks of their party opposition in the electorate, with presidential job approval growing progressively more party polarized. In addition, most of the time, recent presidents’ overall public approval sits below 50 percent. Members of the opposition party see their proper role as obstructing the president’s policies, given that most of their constituents preferred another presidential candidate (and most voters disapprove of the president in any case).

In short, recent presidents come into office demonstrating little capacity to win support from voters who lean toward or support the opposing party. Nothing they do in office changes that reality. Presidents unable to win cross-party support from voters struggle to win cross-party support for their agendas in Congress—support that (as shown) is almost always necessary for successful legislation.

Unilateralism and Overreach

Stymied by opposition in Congress, presidents in the polarized era routinely turn to unilateral action to achieve results on their agenda items. When Barack Obama could not get congressional action on climate change or immigration, he employed unilateral authority to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and the Clean Power Plan. When Trump could not get Congress to pass immigration reform or allocate funding for his border wall, he declared a national emergency and reallocated Pentagon funds for the purpose. When Biden could not induce Congress to pass student loan relief or institute a mandate requiring workers to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, he acted unilaterally. All these cases prompted extensive litigation. In each case, the courts stepped in to restrict or overturn these presidential actions. Despite their frustrations in court, presidents used unilateral actions to show themselves fighting hard for their agenda. But when such actions failed to produce meaningful policy change, presidents blamed other actors for blocking their efforts rather than their own political weakness.

Constrained Parties, Not Low Productivity

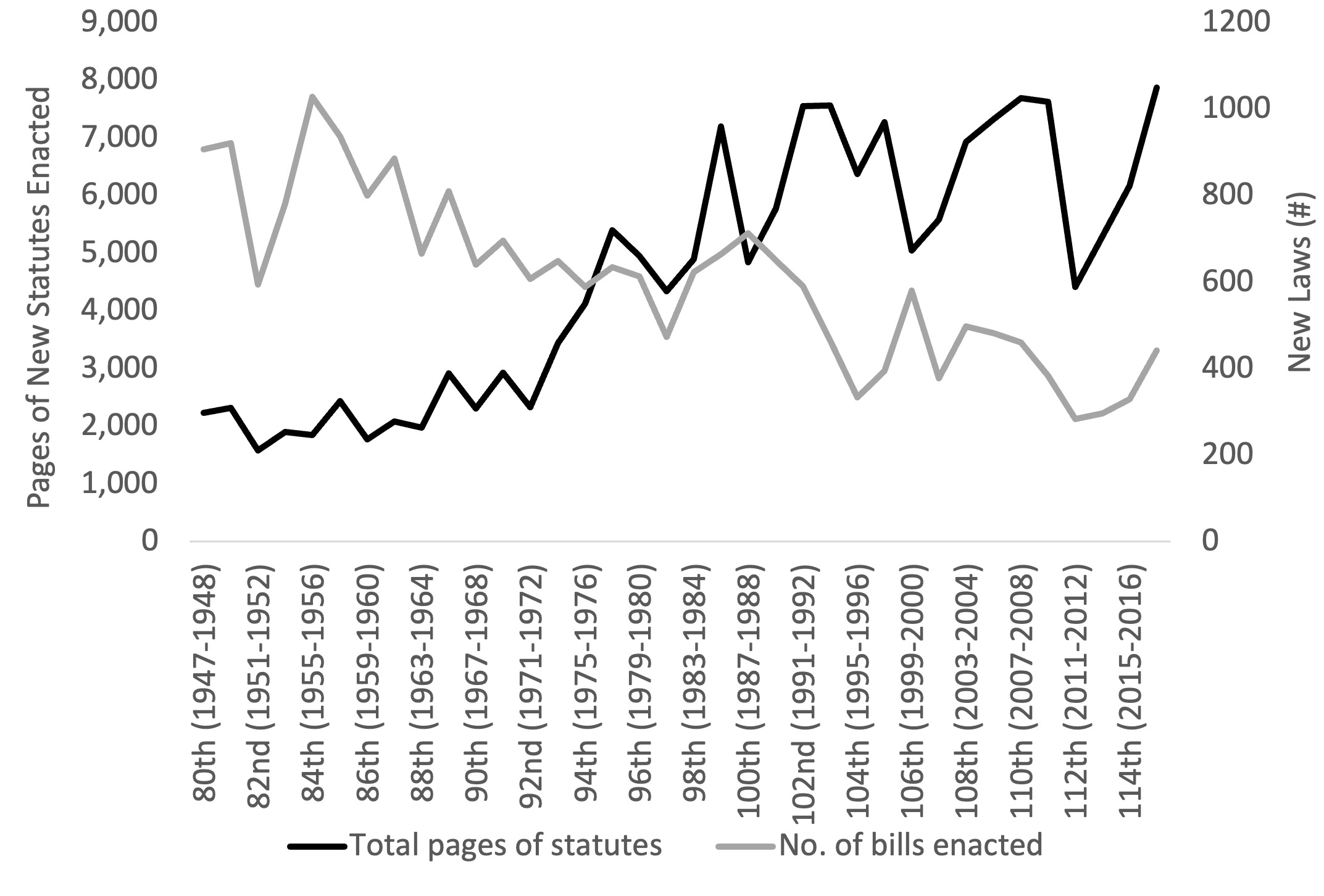

The necessity for bipartisanship does not obstruct legislative action across the board. The gridlock narrative is exaggerated. The polarized Congress is not evidently less legislatively active than the Congress of the 20th century. As gauged by sheer volume, recent Congresses have passed just as much legislation as Congresses of the 1970s and 1980s. As shown in figure 5, the sheer number of pages of legislative text enacted in each two-year Congress has not declined even while the number of individual laws passed per Congress has decreased in an era of omnibus legislating. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, Congress enacted a colossal amount of legislation, including more than $3 trillion of COVID-19 aid under divided government in 2020 alone—by far the most sweeping crisis response in American history. Recent Congresses have shown themselves capable of considerable policy activism on large items and small, most especially in response to widely perceived crisis. In short, there has been a lot of new national policy enacted in recent years but little policymaking on issues where Congress could not reach bipartisan agreement.

Conclusion

Presidents of the party-polarized 21st century stand out for their political weakness, which stems from their persistently low public approval ratings and narrow bases of geographic support. Given these liabilities, it is not surprising that they have struggled to deliver on their partisan agendas via legislation. When there is a broadly felt need to act, presidents have been able to strategically shape legislation to their advantage. (As a crude example, consider President Trump’s insistence that COVID-19 relief checks bear his signature.) But on the issues most closely associated with their campaign promises, the politically weak presidents of our polarized era usually find that they cannot get the bipartisan support that congressional action requires. In such circumstances, they often turn to unilateral action—a poor substitute for legislation in producing lasting policy change.

Endnotes

Eric Bradner and Dan Merica, “Biden Slams Critics of Working with GOP,” CNN Politics, June 17, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/17/politics/joe-biden-dismisses-2020-critics-of-bipartisan-approach/index.html.

The Senate looks less bipartisan than the House under these indicators tracking minority-party support for laws. Note, however, that these indicators are based on recorded votes. Many measures pass the Senate on voice votes or unanimous consent but are not reflected here. Including those measures would make Senate lawmaking look more bipartisan.

On average, 11.7 important laws are enacted per Congress. The minimum number passed in a Congress was six (in the 106th, 1999–2000). The maximum number was 22 (93rd, 1975–76).

The two Senate Republicans whose states Biden carried in 2020 were Pat Toomey (R-PA) and Susan Collins (R-ME).