Presidential Nominations: What about Competence?

Bring peer review back into the presidential nomination process

In December 2015, the Republican Party hosted its third debate for candidates seeking its presidential nomination. As the debate turned to foreign policy, Hugh Hewitt asked Donald Trump, “Mr. Trump . . . what’s your priority among our nuclear triad?”1

What happened next was familiar to anyone who has been a college professor. Like millions of students before him who hadn’t done the reading, Trump tried to bullshit his way out of the question, grasping at straws like Iraq and Syria and hoping he could somehow find the right answer and just get through it.2 He didn’t even pick up on the hint included at the beginning of the question, mentioning bombers, missiles, and submarines. Hewitt tried to help him out by asking a follow-up question that contained a second hint: “Of the three legs of the triad, though, do you have a priority? I want to go to Senator Rubio after that and ask him.”3

But Trump still didn’t get it. His response? “I think—I think, for me, nuclear is just the power, the devastation is very important to me.”4

Like millions of students before him who hadn’t done the reading, Trump tried to bullshit his way out of the question, grasping at straws like Iraq and Syria and hoping he could somehow find the right answer and just get through it.

Senator Rubio then filled in the blanks defining the triad as “our ability of the United States to conduct nuclear attacks using airplanes, using missiles launched from silos or from the ground, and also from our nuclear subs’ ability to attack. And it’s important—all three of them are critical. It gives us the ability at deterrence.”5

Senator Rubio got the right answer, but he didn’t go on to become president and Donald Trump did. And while a few articles appeared pointing out Trump’s profound ignorance on one of the key responsibilities of the president, all in all the episode received very little comment.6

That made sense in the context in which current presidential nomination battles (and general election battles) are fought—after all, most of the voting public has no idea what the nuclear triad is either. But it illustrates one of the biggest problems in our current presidential election system: it is very easy for people to get nominated and elected who do not know the fundamentals of the job of the president.

Peer Review

As Americans, we take for granted that those we entrust with significant authority have been judged by their peers to be competent at the task. Peer review is commonly accepted in most professions. In medicine, for instance, “peer review is defined as ‘the objective evaluation of the quality of a physician’s or a scientist’s performance by colleagues.’”7 We license plumbers, electricians, manicurists, doctors, nurses, and lawyers. We do this in most aspects of life—except politics. In 2016, Americans nominated and then elected Donald Trump, the most unqualified (by virtue of traditional measures of experience and temperament) person ever elected to the Office of the President of the United States, in a system in which peer review had disappeared.

Following the Democratic Party reforms of 1968 to 1972, the nominations process moved from a hybrid system (in which party leaders and elected officials were dominant and primaries played a minor role) to a system totally dominated by primaries in which party leaders played a minor role. “Previously an elite of party leaders performed a screening function. They administered a kind of competence test; they did not always exercise the duty creditably, but they could—did—ensure that no one was nominated who was not acceptable to the preponderance of the party elite as its leader.”8

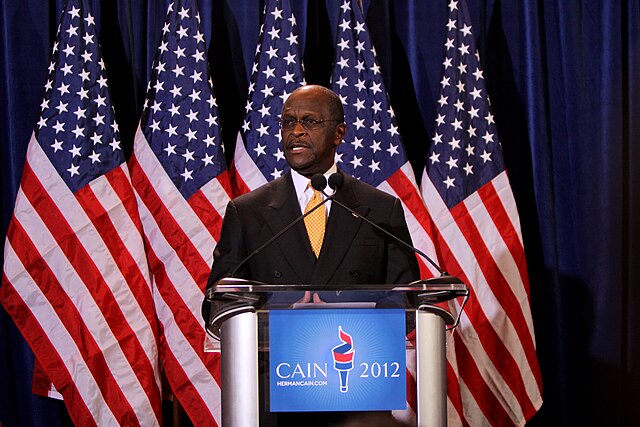

Although it took a few decades, a growing number of nontraditional candidates raised the modest amount of money needed to get on primary ballots and even onto presidential primary debate stages. From a pizza executive to an obscure former senator from Alaska who had been out of office for 28 years before deciding to run for president, to a billionaire with no government experience, to a “spiritual advisor,” both political parties have considered nontraditional presidential candidates.9

Although it took a few decades, a growing number of nontraditional candidates raised the modest amount of money needed to get on primary ballots and even onto presidential primary debate stages.

Most marginal candidates never got through the first primaries. But in 2016, Trump did and became president in an election that sent shock waves throughout the country and the world. His presidency ripped an already polarized country farther apart, sent repeated ripples of fear through our international allies, and repeatedly violated long-standing norms. As he bumbled his way through a pandemic, it became clear that he was not up to the job. As a long list of tell-all books on the Trump presidency illustrate, his aides regularly undermined or ignored his wishes. And more than one student of the presidency has observed that Trump’s short attention span and generally shambolic approach to the presidency was a blessing in disguise—it kept his worst instincts from becoming policy.

The question before us then is this: Is it possible to return some element of peer review to the presidential nomination process? An entire generation of voters has never experienced the old-fashioned method of party-based nominations. Given the antipathy—both historic and current—that Americans hold toward political parties and politicians, a wholesale return to strong parties is hard to imagine. Nonetheless, if we want higher-quality presidents and if we are to be protected from demagogues and incompetents, we may want to reconsider some form of peer review. Following are a few options.

Option 1—Increase the Number and Role of Superdelegates

Presumably, members of Congress and party leaders, many of whom have worked with past presidents, would be sensitive to whether or not the presidential aspirant would have the knowledge, gravitas, and talent in areas like negotiation to actually do the job.

And yet, opposition to the very notion of superdelegates has been a rallying cry for many voters, especially young voters who have no idea that the vast majority of American presidents were nominated by conventions consisting of their fellow party leaders.

Option 2—Conduct a Pre-primary Endorsement Process

Another option would be for each party to mandate a pre-primary endorsement of one or more candidates. In Massachusetts, Democrats hold an annual party convention, and in election years, the convention “endorses” candidates for statewide office. A candidate who does not receive at least 15 percent of the convention votes on the first ballot will not be eligible for placement on the primary ballot. The candidate who wins the majority of votes is the “endorsed” candidate of the Democratic Party and has the first position on the primary ballot, where they are identified as the “endorsed candidate of the Massachusetts Democratic party.”10 This process guarantees that the candidates are at least minimally acceptable to the local leadership of the Democratic Party. Newcomers are regularly kept off the ballot.11

A national endorsing convention would give party officials and activists a big role in limiting who could run for president under the party’s banner, as potential candidates would have to cross a threshold of support to be eligible to be on the ballot. However, as effective as this method is for keeping the party involved in Massachusetts, it would be possible but extremely difficult to pull off on a national level. It would push the race for president even earlier than it now is because delegates would have to be elected in the year before the primaries were held.

Option 3—Issue a Pre-primary Vote of Confidence

A more feasible option might be to have members of Congress and the parties’ national committees give up their automatic convention votes in return for a January session or sessions with the presidential candidates that would allow them to drill the candidates (in private) and then to issue a vote of confidence or no confidence.

Members could be allowed to vote for more than one candidate, and their role would simply be to let the primary voters know what people in government think of the capabilities of these candidates before the beginning of the nomination contests. Candidates not receiving a minimum number of votes—say, 15 percent—from these forums would not be able to join the televised presidential debates.

Another option would be to bar candidates who do not receive a vote of confidence from winning delegates if they manage to get on state ballots.12

The political elites would not be making any final decisions—the voters would still do that—but they would be telling the voters two important things. First, are all of these people knowledgeable and experienced enough to have the judgment to do the job of president? Second, are all of these people in line with the general philosophy of the Democratic or Republican Party?

Candidates pay no price for ignorance of the basics of the job.

Pizza executives with no government experience, retired former senators who have been out of politics for decades, reality television stars, and spiritual advisors may very well not make the cut, but they could still fulfill the ballot requirements to run and win in the primaries. At least the electorate would be formally forewarned.

This approach may not have prevented the nomination of Donald Trump. After all, the Republican establishment offered its warnings about Trump early on—albeit informally. Primary voters in the Republican Party ignored those warnings because they wanted to send a message to their party. But by forcing would-be presidents to appear before the people they need to work with if elected, a pre-primary vote of confidence could add some element of peer review to the process.

Candidates pay no price for ignorance of the basics of the job. How to test for competence while respecting the reality that modern voters expect to have the last word in the nomination process is a challenge—but one worth pondering.

Endnotes

“Transcript: Republican Presidential Debate,” New York Times, December 15, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/16/us/politics/transcript-main-republican-presidential-debate.html.

Here’s Trump’s answer verbatim:

Well, first of all, I think we need somebody absolutely that we can trust, who is totally responsible; who really knows what he or she is doing. That is so powerful and so important. And one of the things that I’m frankly most proud of is that in 2003, 2004, I was totally against going into Iraq because you’re going to destabilize the Middle East. I called it. I called it very strongly. And it was very important.

But we have to be extremely vigilant and extremely careful when it comes to nuclear. Nuclear changes the whole ball game. Frankly, I would have said get out of Syria; get out—if we didn’t have the power of weaponry today. The power is so massive that we can’t just leave areas that 50 years ago or 75 years ago we wouldn’t care. It was hand-to-hand combat.

The biggest problem this world has today is not President Obama with global warming, which is inconceivable, this is what he’s saying. The biggest problem we have is nuclear—nuclear proliferation and having some maniac, having some madman go out and get a nuclear weapon. That’s in my opinion, that is the single biggest problem that our country faces right now.

“Transcript.”

“Transcript.”

“Transcript.”

See Jess Berney, “Trump’s Terrifying Nuke Answer at the Debate Should End His Campaign (but It Won’t),” Rolling Stone, December 16, 2015, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/trumps-terrifying-nuke-answer-at-the-debate-should-end-his-campaign-but-it-wont-34436/.

Lamk Al-Lamki, “Peer Review of Physicians’ Performance,” Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 9, no. 2 (2009): 109–12, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3074768/.

James L. Sundquist, “The Crisis of Competence in Our National Government,” Political Science Quarterly 95, no. 2 (1980): 180–208, 193.

Herman Cain ran for the Republican Party nomination in 2012. He was chairman and CEO of Godfather’s Pizza. Mike Gravel had been senator from Alaska from 1969 to 1981.

See Convention Rules of the Massachusetts Democratic Party, pp. 3–4; Massachusetts Democratic Party, “Proposed Rules of the 2018 Massachusetts Democratic Endorsing Convention,” https://massdems.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2018-Convention-Rules-APPROVED.pdf.

For instance, in the 2014 Democratic Convention, Juliette Kayyem, a former Obama administration official, failed to reach the 15% threshold at the convention and was not on the primary ballot.

Political parties have the right to say who can win delegates on a state ballot. In 1996, Democratic Party Chair Don Fowler ruled that Lyndon LaRouche could not win any delegates in the states where he had gotten onto the ballot. The case went to the Supreme Court and Fowler won. See Casetext, “Larouche v. Fowler” (1998), https://casetext.com/case/larouche-v-fowler.