On Transparency and Presidential Accountability

Transparency is necessary for presidential accountability to work

We often think of the presence or absence of presidential accountability in terms of whether the president is constrained by sharp legal restrictions enforceable through criminal sanctions or some other form of legally enforceable restraint. This is certainly a key element of the program of presidential accountability. But it is also complicated in execution by knotty constitutional issues, not to mention the political conflicts that erupt over proposals for various kinds of formal limits on the exercise of presidential power.

In fact, “accountability” has a much broader meaning. It means that an actor, including the president, is subject to an account, which in turn requires that the actor must disclose his or her activities, explain and answer for them, and subject himself or herself to the consequences of the institution or group to which one is accounting.

On this broader view, accountability includes a whole array of sanctions by a whole array of actors, including prosecutors, inspectors general, congressional committees, the press, civil society, and, ultimately, the public, who can impose a whole array of sanctions, including—depending on the actor—prosecution, hearings, subpoenas, reprimand, accountability journalism, advocacy campaigns, impeachment, and electoral rebuke.

On this broader view, accountability includes a whole array of sanctions by a whole array of actors . . .

Transparency in some form is a necessary condition for all of these accountability mechanisms to work. Only if the actions of the president and his or her subordinates are known to these adversary actors can accountability work. That, in a nutshell, is why transparency is so important to almost all accountability initiatives. And transparency has a secondary advantage: often members of Congress or those crafting executive branch norms can agree on rules about transparency even if they cannot agree on the rules about whether or not certain presidential behaviors should be prohibited.

Transparency in some form is a necessary condition for all of these accountability mechanisms to work.

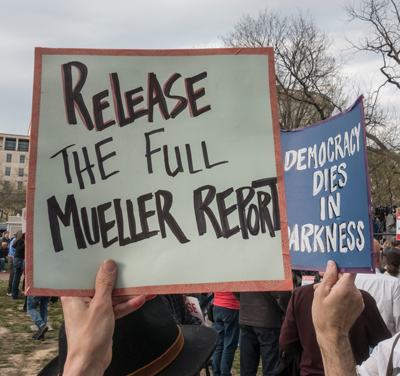

Transparency-induced political constraints were an underappreciated but vital check on Donald Trump’s aberrant behavior during his presidency.

Time after time, Trump’s actions were brought to the public’s attention by leaks, press reports, subpoenas, and the like and induced political actors—including some Republicans in Congress and inside the executive branch—to prevent Trump from, for example, firing Special Counsel Robert Mueller and to prevent him from following through on many of his other norm-breaking or law-defying threats.

These are some of the reasons why various reforms and reform initiatives in recent years have been grounded primarily in transparency mandates.

In December 2022, Congress enacted sweeping reform of the Case Act governing transparency of presidential agreement-making.1 The reform expanded the executive branch’s duty to report and make public both binding and nonbinding executive branch agreements. The basic idea is that such reporting and transparency will better enable Congress, supported by outside actors, to monitor and review executive branch agreements and push back, through various means, on ones deemed problematic or unacceptable in some sense. In turn, this review will discipline the executive branch to keep Congress in the loop on its agreements or at least to avoid ones that will invite such pushback.

The executive branch’s broad authority to interpret the Constitution, combined with its broad views of Article II, can lead to dangerously broad interpretations of Article II, especially when the interpretations take place in secret.

Consider the recent trend of securing publication of Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) opinions through the Freedom of Information Act and of proposals to institutionalize the publication of OLC opinions. The executive branch’s broad authority to interpret the Constitution, combined with its broad views of Article II, can lead to dangerously broad interpretations of Article II, especially when the interpretations take place in secret. Publication can hold these opinions up to public scrutiny, allow Congress and other actors to push back, and, hopefully, discipline or temper unduly expansive executive legal interpretations going forward.

In After Trump, we proposed an array of reforms of the presidency that are premised on enhanced transparency, including mandatory disclosure of tax filings by presidential candidates, mandatory disclosure of the financial arrangements of presidents to bring to light conflicts of interest, transparency of decision-making by the attorney general in his special counsel decisions, and more.2

One might have imagined that certain of these proposals would have found a wide, bipartisan audience.

One might have imagined that certain of these proposals would have found a wide, bipartisan audience. For example, for years until Donald Trump refused to do so, presidential candidates and presidents (and their running mates) voluntarily released their tax filings. It seemed that a norm so ingrained in the political culture would present a relatively noncontroversial case for legislation both major parties could support. And yet, despite bills introduced in both houses, nothing happened.

No doubt the issue was so identified with Trump that his party saw a reasonable policy measure as a partisan attack or feared that the 2020 (and perhaps future) standard-bearer would view and denounce such a measure in those terms. This was a case where a straightforward issue that had garnered bipartisan support as a norm for decades became thoroughly politicized. The experience suggests that for transparency to retain its potency in a polarized political environment, it might require the configuration of proposals to minimize or contain political conflict. The tools available for this purpose could include deferred effective dates or specialized formats for reporting rather than the release of raw returns. The law could set a “floor,” and then the political marketplace would kick in. Candidates (and presidents) could decide to provide more rather than less, or release sooner rather than later, if they perceived a strategic or messaging advantage in doing so.

To be sure, transparency mandates face challenges beyond the purely political. Not every transparency mandate is constitutional. The presidency has a zone of privileged deliberation and secret action that has long been seen as vital to the efficacy of executive branch action. Ill-advised transparency mandates can stifle executive branch deliberation and unduly chill executive branch action. This balance must always be kept in mind and taken into account.

Ill-advised transparency mandates can stifle executive branch deliberation and unduly chill executive branch action.

And, of course, transparency mandates ultimately work only if other institutions in the political system, and the American people, act on the information to check an abusive president. As noted, we believe that transparency operated much more extensively and fruitfully during the Trump administration to check abusive actions than has been appreciated. But there is no guarantee that it will continue to work. If a political system becomes so degraded and fragmented that political checks lose all or most of their bite, then no legal reform can help prevent abuse in this context.

Endnotes

Case-Zablocki Act of 1972, 1 U.S. Code § 112b.

Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith, After Trump: Reconstructing the Presidency (Washington, DC; Lawfare, 2020).