What Americans Still Want from Government Reform

Seven trends to guide bureaucratic improvements

The 2024 presidential campaign is certain to produce a long list of make-or-break debates. Federal government performance may yet spark an electoral debate about federal performance and demand for a bigger government that delivers more services, and rising pressure for very major government reform. Much as Americans support very major government reform, the seven trends presented in this essay suggest caution instead.1

Trend 1

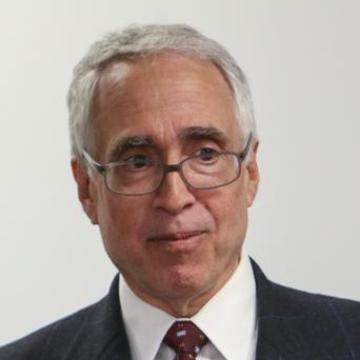

The federal government’s job rating is falling.

As figure 1 shows, the federal government’s job rating for running its programs has been stuck in low since 2015 and shows no sign of a rebound. Although Biden’s ratings moved up to a 77 percent fair/poor total after his 2020 victory, his totals dropped sharply after the bloody Afghanistan withdrawal and slipped further as inflation took the spotlight. Moreover, Biden’s 77 percent total was evenly split between fair and poor, hardly a sign of common ground.2

Trend 2

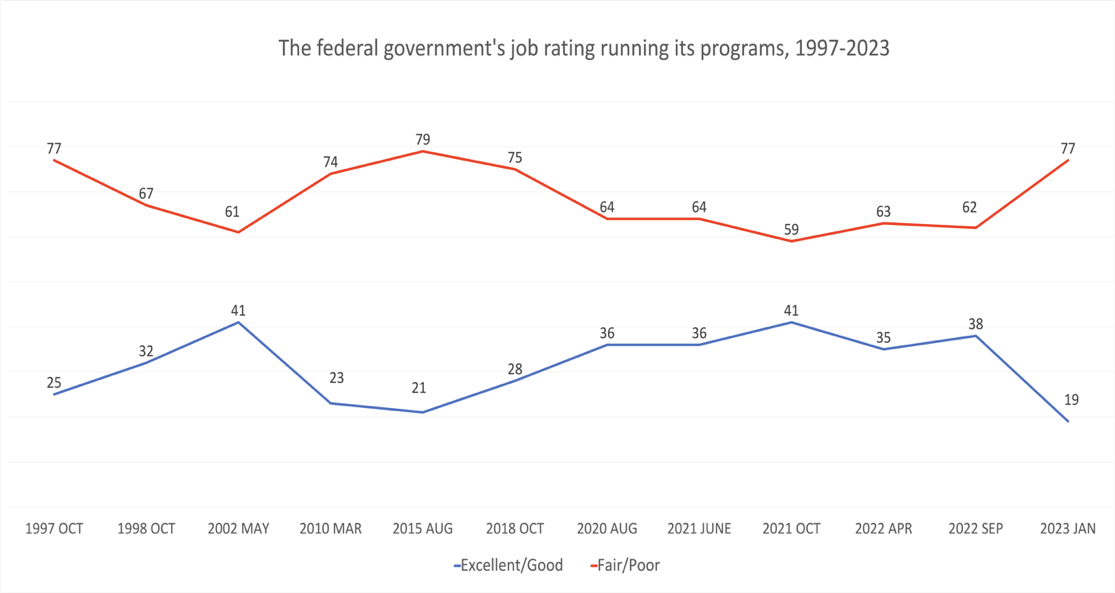

Americans are leaning toward smaller government and fewer services.

As figure 2 shows, Biden moved toward his inauguration in 2021 with support for a smaller government that delivers fewer services, up from 38 percent to 50 percent. Public demand for a smaller government that delivers fewer services held steady in the mid-40 percent range, while support for a bigger government that delivers more services was cut in half.

Trend 3

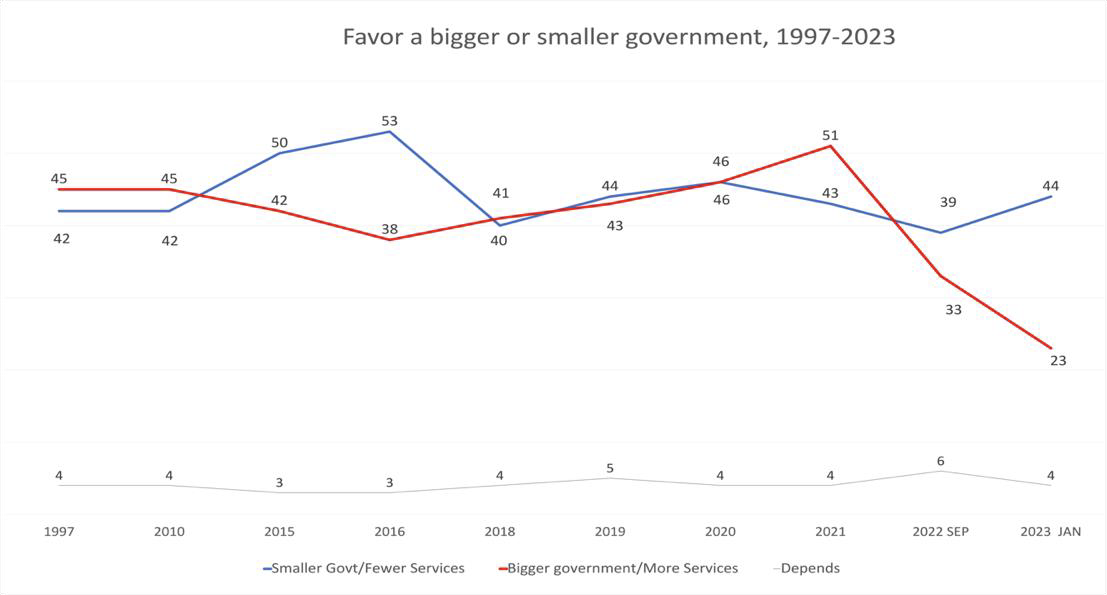

Support for very major government reform is at a recent high.

As figure 3 shows, public support for major government reform dropped slightly during Biden’s 2021 honeymoon before rising with economic worries and the bloody Afghanistan war. If ever a president needed a government reform agenda to energize the electorate, it is Biden. It was lost in the Biden-Harris Management Agenda and its vague commitment to an "Equitable, Effective, and Accountable Government that Delivers Results for All."3

Trend 4

Public dissatisfaction toward government rose during Biden’s first three years as demand for very major reform hit a 63 percent high.

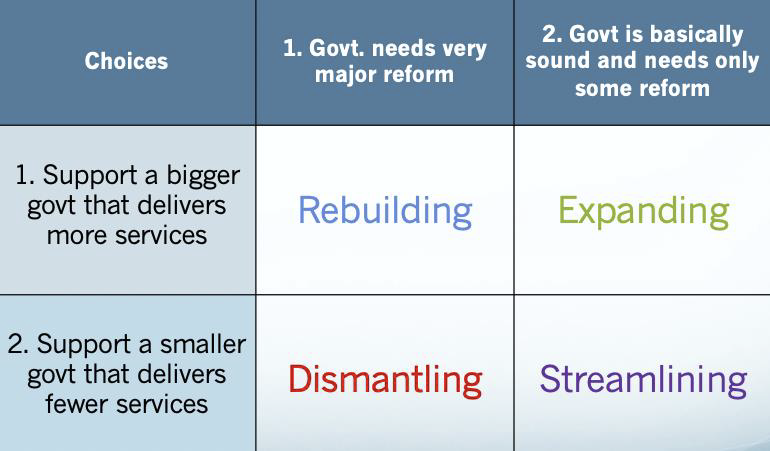

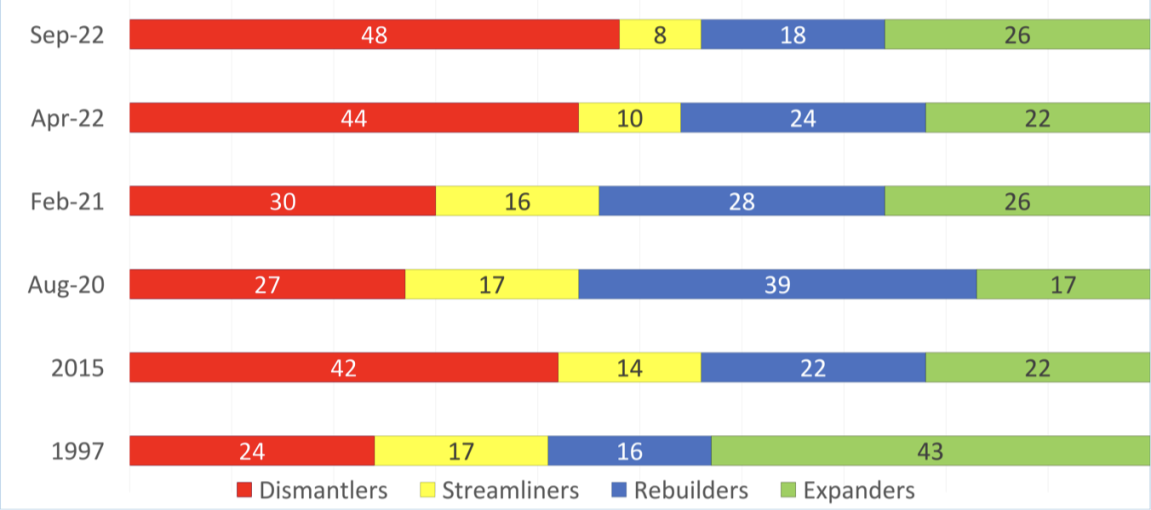

The four reform positions are described in figure 4. As figure 5 suggests, support for major reform and smaller government (dismantling) is also on the rise, while support for bigger government and only some reform (expanding) is down.

Figure 5 shows the reform movement over time with presidential promises such as Bill Clinton’s commitment to a government that "works better and costs less," George W. Bush’s call for "active, but limited, engaged, but not overbearing government," Donald Trump’s promise to "cut so much your head will spin," and Biden’s long-forgotten Management Agenda vision.

Trend 5

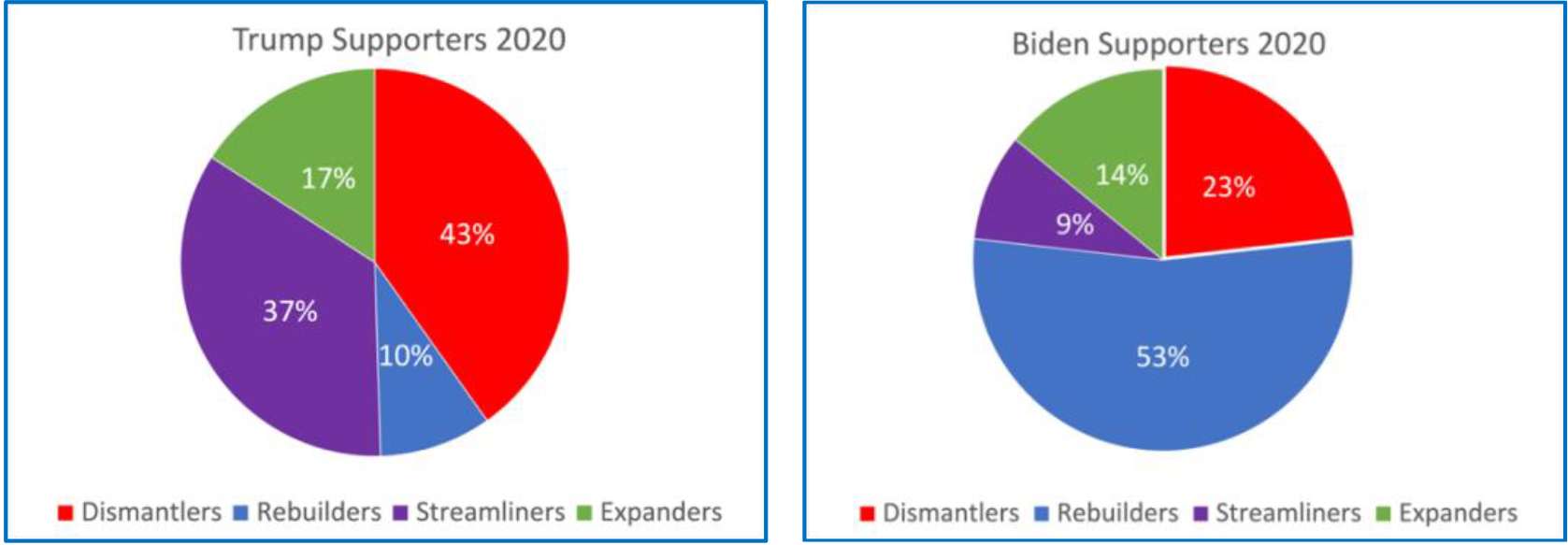

Trump supporters put government reform on their agenda with a demand for smaller government and fewer services, while Biden supporters put government reform on their agenda with a demand for more services and bigger government.

As shown in figure 6, Biden supported government reform and earned support from the 53 percent of respondents who favored a bigger government and major reform (rebuilding). Trump rarely missed an opportunity to attack government fraud, waste, and abuse, with support from the 43 percent of respondents who favored a smaller government and major reform (dismantling).4

Trend 6

The number of federal government breakdowns is rising in the absence of White House engagement.

Defined as a highly visible failure in the design, implementation, and day-to-day operation of a federal program or policy, the number of federal breakdowns per year has grown during every presidency since Watergate.

Biden followed suit with six highly visible government breakdowns in his first year alone, including a global supply chain collapse and computer chip shortage, the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack in May 2021, and the Afghanistan withdrawal in late August, and eight more in his second year including the baby-formula shortage.

Based on my ongoing analysis of recent federal government breakdowns dating back to the Ford presidency, most of the 200 breakdowns on my list were driven more by budget and staffing shortages, weak leadership, political meddling, bureaucratic layering, broken chains of command, and the erosion of state capacity.5

As table 1 suggests, breakdowns often occur in broken agencies that generate breakdown after breakdown without repair. They occur in highly visible agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Federal Aviation Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Table 1. Federal Agencies with High Breakdown Totals, 2020–2023

| Agency |

|---|---|

1. | Internal Revenue Service |

2. | Food and Drug Administration |

3. | U.S. Postal Service |

4. | Federal Bureau of Investigation |

5. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

6. | Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Railroad Administration, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration |

7. | Federal Emergency Management Agency |

8. | Federal Trade Commission |

9. | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

10. | Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Reserve Board, Treasury Department |

11. | U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

12. | United States Coast Guard |

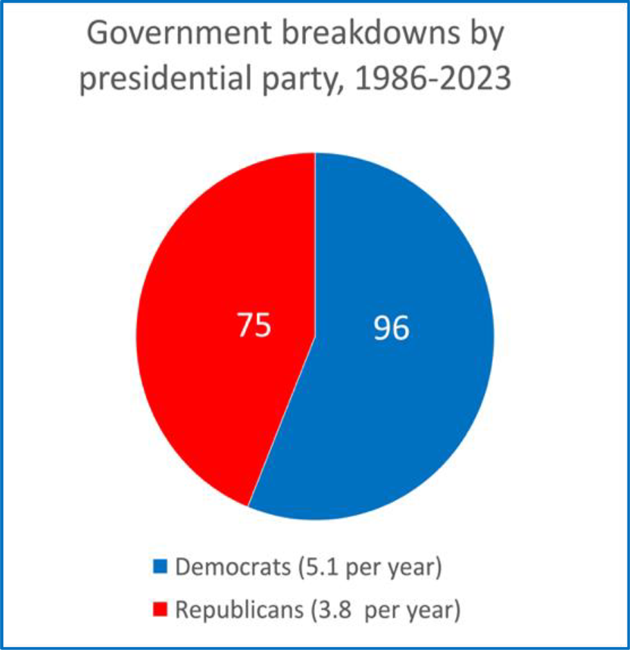

Much as partisanship often shapes the narrative about government failures in these and other federal agencies, figure 7 suggests that Democrats and Republicans both face significant numbers of breakdowns on their watches, yet presidential scholars have yet to fully embrace government breakdowns as a common threat to and concern for presidential success.

Trend 7

Biden has been slow to embrace government reform as an answer to the early breakdowns on his watch.

Despite Biden’s early Senate interest in battling government fraud, waste, and abuse, he has shown little interest in it in recent years. Biden had ample reason to criticize Trump’s "irrational downplaying" during the 2020 SolarWinds hack but continues to ignore government reform.6 Asked during his vice presidential vetting if he "would be very happy" to reorganize the federal government as a vice presidential assignment, Biden answered, "No, that’s not what I want to do."7 He has yet to change his mind.

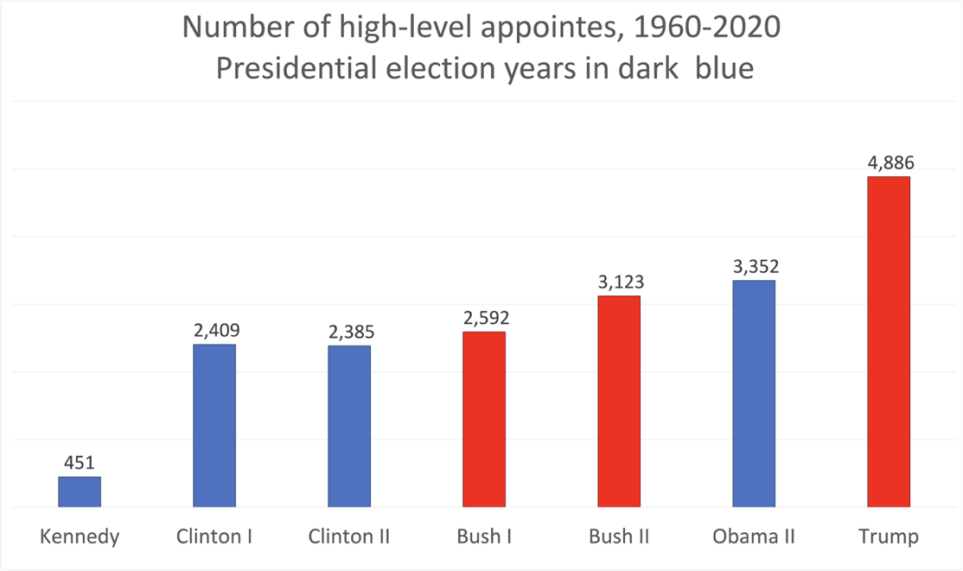

Biden can reverse course by addressing the breakdowns left behind when Trump became president. He might also find public applause in tackling the presidential appointments system that continues to dilute accountability and delay presidential accountability. Given the number of appointees (fig. 8) and the thicket of duplication and delay they generate, Biden would be well advised to embraces bureaucratic reform as something he absolutely wants to do.

As this essay suggests, presidents too often ignore the administrative scaffolding essential for faithful execution of the laws they sign when they should start fixing broken agencies and systems the minute they take the Oath of Office. Much as presidents and their policy staffs might be drawn to self-executing policies built on nudges and incentives, faithful execution remains vulnerable to the broken systems waiting for repair.

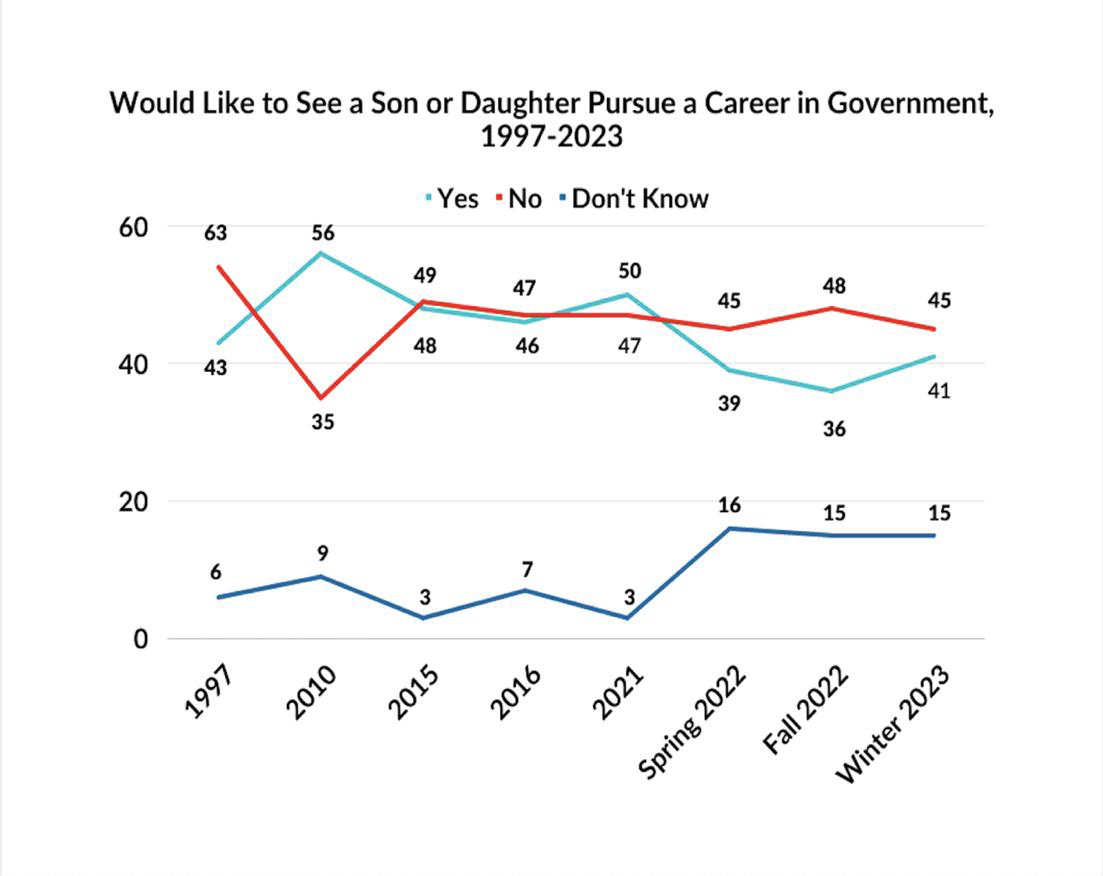

Meanwhile, presidents must take care to replenish the federal government’s capacity by calling younger citizens to service. Unfortunately, recent surveys show a slight decline, from 56 percent positive in 2010 to 36 percent in 2022, in the interest in government careers.

As figure 9 shows, parental resistance to government careers for their sons and daughters grew from 35 percent in 2010 to 48 percent in 2022, with no evidence of a presidential response. Democrats and Republicans have long disagreed on the value of government careers, but the reluctance seems to be hardening lately.

Endnotes

The public opinion surveys used in this essay were designed and executed by the Pew Research Center, SSRS, and Maguire Research Services. All surveys were conducted by telephone with at least 750 randomly selected respondents per survey, but the Maguire 2021 and 2022 surveys had 1,000 respondents each. Other survey findings in this essay come from publicly available reports from the CBS News Poll, CNN/ORC, Gallup, Hill-Harris X, Kaiser Family Foundation, Maguire Research Services, Morning Consult, NPR/PBS, Rasmussen, Reuters/Ipsos, Washington Post–ABC News Poll, and You Gov. The survey data presented in this essay were generally collected in spring or summer.

For further discussion of public opinion toward federal performance, see my analysis of recent polls; Paul C. Light, "Biden’s Dilemma, Part 1: The Federal Government’s Job Rating Has Dropped by Half," Government Executive, April 10, 2023, https://www.govexec.com/management/2023/04/bidens-dilemma-part-1-federal-governments-job-rating-has-dropped-half/384920/.

Joseph Biden, "The Biden-Harris Management Agenda Vision," Performance.gov, https://www.performance.gov/pma/vision/.

The 2022 survey results can be viewed at "Pew Research Center: American’s Views of Government: Decades of Distrust, Enduring Support for Its Role. 2. Public Views about the Federal Government," June 6, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/06/06/2-public-views-about-the-federal-government/.

For an analysis of the federal government to execute the laws and an introduction to role of state capacity in maintaining organizational capacity, see Brink Lindsey, "State Capacity: What Is It, How We Lost It, and How to Get It Back," Niskanen Center, November 18, 2021, https://www.niskanencenter.org/state-capacity-what-is-it-how-we-lost-it-and-how-to-get-it-back/. See also the list of federal government agencies that have shown significant capacity deficits in recent years (table 1).

The total number of presidential appointee positions presented in fig. 7 can be found in my hand counts of presidential appointee titles listed in the Washington Monitor phone books from 1960 to 2023, while the layers of government and number of positions identified in 2022 come from hand counts of senior titles listed in the Leadership Connect searchable online directory.

Ryan Lizza, “Biden’s Brief,” New Yorker, October 13, 2008, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/10/20/bidens-brief.