Growing up Kennedy

Raised in a political dynasty, Kennedy recounts what inspired his own approach to public service

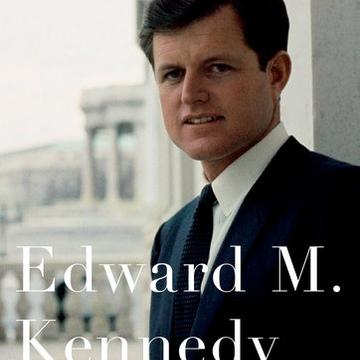

[Excerpted from chapter 1 of Edward M. Kennedy: An Oral History, by Barbara Perry]

The last of Joseph and Rose Kennedy’s nine children arrived on February 22, when his mother was 41 years old. Well-meaning friends thought her foolish to have a ninth baby at her age. Because the child was born on George Washington’s birthday, Jack, his waggish 15-year-old brother, lobbied to name him for the first president, but they resisted and christened him Edward Moore Kennedy, after his father’s faithful secretary.

After attending 10 primary and secondary schools, Teddy followed his brothers and father to Harvard but was suspended after his freshman year for cheating on a final exam. Harvard readmitted Kennedy upon completion of his two-year army enlistment, spent primarily on a NATO base near Paris. Teddy had wanted to volunteer for the Korean conflict, but his brothers begged him not to, out of deference to their parents’ grief suffered at the loss of Joe Kennedy Jr. in World War II. Despite the plum assignment in France, the army exposed young Kennedy to strata he had not known as a son of privilege. The experience would also make him a leading advocate for military veterans throughout his Senate career.

Following his Harvard graduation, Teddy enrolled in the University of Virginia Law School, as had his older brother Bobby, and served as Jack’s campaign chairman for his 1958 Senate re-election. Just after Jack’s successful 1958 campaign, Teddy married Joan Bennett, whom he had met at his sister Jean’s alma mater, Manhattanville College. They would have three children, Kara (1960), Edward Jr. (1961), and Patrick (1967).

Edward M. Kennedy: I think the one sort of overarching sense that we [the Kennedy family] all had is we were enormously happy together. Our best friends were our brothers and sisters. We enjoyed doing things together. There may have been times when my father and mother weren’t present, but we really were never conscious of it.

One thing that has struck me over the time that I’ve become older and realize the political activities of our whole family. I don’t remember ever, a single political event taking place in our home, either Cape Cod or in Florida.... Home was always a place where we gathered and it was sort of our space and time. That was just the atmosphere and the climate that we grew up in. My brothers used to joke that my sisters would never get married, because they were having such a good time with my brothers....

We took trips with our mother at very early ages, to visit historic places in Massachusetts: Plymouth, Walden Pond, the historic sites in Boston, Paul Revere’s home. This sort of fit in to what my grandfather [John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald] had done with me, I mean this was sort of a continuum.

I can look out my window next to my desk [in Boston] and see where my grandfather was born on Ferry Street and where my mother was born on Garden Court Street. My father was born on Meridian Street in East Boston; that’s fairly blocked. I can also see the old North Church and St. Stephen’s Church, the Bunker Hill Monument, the Constitution. And if you lean out a little bit and look to the right, you can see Faneuil Hall.

This is the whole birthplace of America, and down the sweep of the harbor, I can see the building where eight of my forebears came in 1848, out of one window, which is absolutely unique and special. That’s a very inspiring location.

Where all of the ships, all the immigrant ships, came in and passed to the docks. The docks are still there, where my great-grandparents came in, in 1848. Eight of them came in, and the steps are still there, where they walked on American soil. They’re called the golden steps, because it was the golden steps into opportunity, into the United States….

As I think back on the times of politics...the presence of my grandfather emerges as a larger and larger figure, because I did spend a good deal of time at a very impressionable age, and I had a close, warm personal relationship where he was sort of my father, a member of my family when I was first off at boarding school…. He was outgoing and warm, and he was able to break through people’s barriers and reticence, and do it in an expansive, warm, lovely way. These were my first observations of what you really talk about in politics, and what is most important—how you’re going to relate to people….

I think my brother interacted with him, but in an entirely different kind of relationship. When my brother was running, Grandpa was a figure, and I think he didn’t know whether he did or didn’t want Grandpa there. But for me, he was an ideal, and extraordinarily unique. I had not seen those qualities in my own family, and the more I observed it, the more I learned about him, he was just an incredible phenomenon, a character. His inquisitiveness into life and people and events, and the joy he got out of knowing everything was enormously instructive….

If politics was going to be your game, he was the name. I was struck more by the personal association and contact and the joy he had in it. Obviously, to a child, the issues were somewhat blurred, but the idea that he would sing and get people aroused and interested and enthusiastic and be able to identify and attract people to him was the incredible ingredient. And my reading of the period tied into this. I can’t remember now whether it was my reading or whether Grandpa told me about how when he was first in public office, the Irish were too poor to buy newspapers. So they’d say to him, “How do you stand, Honey Fitz? How do you stand?” And he’d effectively tell them his position on whatever it was, and that was good enough for them. I think the people at that time made their judgments and decisions about politicians from the heart more than from the mind. I think, looking back over history, it’s probably that they’ll continue to make some mistakes in doing it, but they’ll be more right than wrong, even today. But it was the way that people identified politics….