Impeachment in the 1780s

For Americans debating the Constitution, impeachment was a critical issue

James Madison

The Federal Convention, July 20, 1787

Mr. MADISON thought it indispensable that some provision should be made for defending the Community agst the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief Magistrate. The limitation of the period of his service, was not a sufficient security. He might lose his capacity after his appointment. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers. The case of the Executive Magistracy was very distinguishable, from that of the Legislature or of any other public body, holding offices of limited duration. It could not be presumed that all or even a majority of the members of an Assembly would either lose their capacity for discharging, or be bribed to betray, their trust. Besides the restraints of their personal integrity & honor, the difficulty of acting in concert for purposes of corruption was a security to the public. And if one or a few members only should be seduced, the soundness of the remaining members, would maintain the integrity and fidelity of the body. In the case of the Executive Magistracy which was to be administered by a single man, loss of capacity or corruption was more within the compass of probable events, and either of them might be fatal to the Republic.

Tench Coxe (“An American Citizen”)

Independent Gazetteer (Philadelphia), September 28, 1787

They [the Senate] can only, by conviction on impeachment, remove and incapacitate a dangerous officer, but the punishment of him as a criminal remains within the province of the courts of law to be conducted under all the ordinary forms and precautions, which exceedingly diminishes the importance of their judicial powers. They are detached, as much as possible, from local prejudices in favour of their respective states, by having a separate and independent vote, for the sensitive and conscientious use of which, every member will find his person, honor and character seriously bound—He cannot shelter himself, under a vote in behalf of his state, among his immediate colleagues. As there are only two, he cannot be voluntarily or involuntarily governed by the majority of the deputation—He will be obliged, by wholesome provisions, to attend to his public duty, and thus in great national questions must give a vote of the honesty of which, he will find it necessary to convince his constituents.

Letters from the Federal Farmer, 3

October 10, 1787

All officers are impeachable before the senate only—before the men by whom they are appointed, or who are consenting to the appointment of these officers. No judgment of conviction, on an impeachment, can be given unless two thirds of the senators agree. Under these circumstances the right of impeachment, in the house, can be of but little importance; the house cannot expect often to convict the offender; and, therefore, probably, will but seldom or never exercise the right.

Note: From the third of 18 essays arguing against the proposed Federal Constitution published in various places. The series is sometimes attributed to Virginia's Richard Henry Lee, but recent historians have noted stylistic differences calling this into question, and the identity of the author is uncertain.

Dissent of the Minority of the Pennsylvania Convention

Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia), December 18, 1787

The next consideration that the constitution presents, is the undue and dangerous mixture of the powers of government: the same body possessing legislative, executive, and judicial powers. The senate is a constituent branch of the legislature, it has judicial power in judging on impeachments, and in this case unites in some measure the characters of judge and party, as all the principal officers are appointed by the president-general, with the concurrence of the senate and therefore they derive their offices in part from the senate. This may biass the judgments of the senators, and tend to screen great delinquents from punishment.

Luther Martin “The Genuine Information”, IX

Maryland Gazette (Baltimore), January 29, 1788

It was further observed, that the only appearance of responsibility in the president, which the system holds up to our view, is the provision for impeachment; but that when we reflect that he cannot be impeached but by the house of delegates, and that the members of this house are rendered dependant upon, and unduly under the influence of the president, by being appointable to offices of which he has the sole nomination, so that without his favour and approbation, they cannot obtain them, there is little reason to believe that a majority will ever concur in impeaching the president, let his conduct be ever so reprehensible, especially too, as the final event of that impeachment will depend upon a different body, and the members of the house of delegates will be certain, should the decision be ultimately in favour of the president, to become thereby the objects of his displeasure, and to bar to themselves every avenue to the emoluments of government.

James Iredell (“Marcus”) in reply to George Mason’s “Objections to the Constitution”

Norfolk and Portsmouth Journal, February 20, 1788

As to the power of trying impeachments, let Mr. Mason shew where this power could have more properly been placed [instead of in the Senate]. It is a necessary power in every free government, since even the Judges of the Supreme Court of Judicature themselves may require a trial, and other public officers might have too much influence before an ordinary and common Court. And what probability is there that such a Court acting in so solemn a manner, should abuse its power (especially as it is wisely provided that their sentences shall extend only to removal from office and incapacitation) more than any other Court? The argument as to the possible abuse of power, as I have before suggested, will reach all delegation of power whatever, since all power may be abused where fallible beings are to execute it; but we must take as much caution as we can, being careful at the same time not to be too wise to do anything at all.

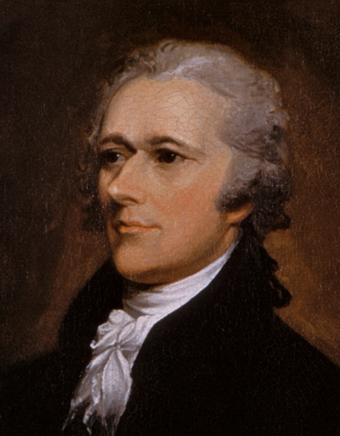

Alexander Hamilton (“Publius”), The Federalist LXIX

New York Packet, March 14, 1788

The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law. The person of the king of Great Britain is sacred and inviolable; there is no constitutional tribunal to which he is amenable; no punishment to which he can be subjected without involving the crisis of a national revolution. In this delicate and important circumstance of personal responsibility, the President of Confederated America would stand upon no better ground than a governor of New York, and upon worse ground than the governors of Maryland and Delaware.

Note: Hamilton's Federalist XLV deals with impeachment exclusively, so we have made it available on its own page.

“A Feeman” to the Freeholders and Freemen of Rhode Island

Newport Herald (Rhode Island), March 20, 1788

The King

The Constitution of England not only views the King as absolute in perpetuity, but in perfection. The King can do no wrong, is an established maxim.

The President

The Constitution of the United States supposes that a President may do wrong, and have provided that he shall be removed from office on impeachment and conviction of high crimes and misdemeanors.

“Brutus” XV

New York Journal, March 20, 1788

The only clause in the constitution which provides for the removal of the judges from office, is that which declares, that “the president, vice-president, and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office, on impeachment for, and conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” By this paragraph, civil officers, in which the judges are included, are removable only for crimes. Treason and bribery are named, and the rest are included under the general terms of high crimes and misdemeanors. — Errors in judgment, or want of capacity to discharge the duties of the office, can never be supposed to be included in these words, high crimes and misdemeanors. A man may mistake a case in giving judgment, or manifest that he is incompetent to the discharge of the duties of a judge, and yet give no evidence of corruption or want of integrity. To support the charge, it will be necessary to give in evidence some facts that will show, that the judges committed the error from wicked and corrupt motives.

James Iredell

North Carolina Ratifying Convention, July 28, 1788

In that country [Great Britain] the executive authority is vested in a magistrate who holds it by birth-right. He has great powers and prerogatives; and it is a constitutional maxim, that he can do no wrong. We have experienced that he can do wrong, yet no man can say so in his own country. There are no courts to try him for any crimes; nor is there any constitutional method of depriving him of his throne. If he loses it, it must be by a general resistance of his people contrary to forms of law, as at the revolution which took place about a hundred years ago. It is therefore of the utmost moment in that country, that whoever is the instrument of any act of government should be personally responsible for it, since the King is not; and for the same reason, that no act of government should be exercised but by the instrumentality of some person, who can be accountable for it. Every thing therefore that the King does must be by some advice, and the adviser of course answerable. Under our Constitution we are much happier. No man has an authority to injure another with impunity. No man is better than his fellow-citizens, nor can pretend to any superiority over the meanest man in the country. If the President does a single act, by which the people are prejudiced, he is punishable himself, and no other man merely to screen him. If he commits any misdemeanor in office, he is impeachable, removable from office, and incapacitated to hold any office of honour, trust or profit. If he commits any crime, he is punishable by the laws of his country, and in capital cases may be deprived of his life. This being the case, there is not the same reason here for having a Council, which exists in England.

James Iredell

North Carolina Ratifying Convention, July 28, 1788

I beg leave to observe, that when any man is impeached, it must be for an error of the heart, and not of the head. God forbid, that a man in any country in the world, should be liable to be punished for want of judgment. This is not the case here. As to errors of the heart there is sufficient responsibility. Should these be committed, there is a ready way to bring him to punishment. This is a responsibility which answers every purpose that could be desired by a people jealous of their liberty. I presume that if the President, with the advice of the Senate, should make a treaty with a foreign power, and that treaty should be deemed unwise, or against the interest of the country, yet if nothing could be objected against it but the difference of opinion between them and their constituents, they could not justly be obnoxious to punishment. If they were punishable for exercising their own judgment, and not that of their constituents, no man who regarded his reputation would accept the office either of a Senator or President. Whatever mistake a man may make, he ought not to be punished for it, nor his posterity rendered infamous. But if a man be a villain, and wilfully abuses his trust, he is to be held up as a public offender, and ignominiously punished.

A public officer ought not to act from a principle of fear. Were he punishable for want of judgment, he would be continually in dread. But when he knows that nothing but real guilt can disgrace him, he may do his duty firmly if he be an honest man, and if he be not, a just fear of disgrace, may perhaps, as to the public, have nearly the effect of an intrinsic principle of virtue. According to these principles, I suppose the only instances in which the President would be liable to impeachment, would be where he had received a bribe, or had acted from some corrupt motive or other. If the President had received a bribe without the privity or knowledge of the Senate, from a foreign power, and had, under the influence of that bribe, had address enough with the Senate, by artifices and misrepresentations, to seduce their consent to a pernicious treaty--if it appeared afterwards that this was the case, would not that Senate be as competent to try him as any other persons whatsoever? Would they not exclaim against his villainy? Would they not feel a particular resentment against him for their being made the instrument of his treacherous purposes? In this situation, if any objection could be made against the Senate as a proper tribunal, it might more properly be made by the President himself, lest their resentment should operate too strongly, rather than by the public, on the ground of a supposed partiality. The President must certainly be punishable for giving false information to the Senate. He is to regulate all intercourse with foreign powers, and it is his duty to impart to the Senate every material intelligence he receives. If it should appear that he has not given them full information, but has concealed important intelligence which he ought to have communicated, and by that means induced them to enter into measures injurious to their country, and which they would not have consented to had the true state of things been disclosed to them--In this case, I ask whether, upon an impeachment for a misdemeanor upon such an account, the Senate would probably favour him?

James Madison

Speech in Congress, June 16, 1789

When we consider that the first magistrate is to be appointed at present by the suffrages of three millions of people, and in all human probability in a few years time by double that number, it is not to be presumed that a vicious or bad character will be selected. If the government of any country on the face of the earth was ever effectually guarded against the election of ambitious or designing characters to the first office of the state, I think it may with truth be said to be the case under the constitution of the United States. With all the infirmities incident to a popular election, corrected by the particular mode of conducting it, as directed under the present system, I think we may fairly calculate, that the instances will be very rare in which an unworthy man will receive that mark of the public confidence which is required to designate the president of the United States. Where the people are disposed to give so great an elevation to one of their fellow citizens, I own that I am not afraid to place my confidence in him; especially when I know he is impeachable for any crime or misdemeanor, before the senate, at all times; and that at all events he is impeachable before the community at large every four years, and liable to be displaced if his conduct shall have given umbrage during the time he has been in office. Under these circumstances, although the trust is a high one, and in some degree perhaps a dangerous one, I am not sure but it will be safer here than placed where some gentlemen suppose it ought to be.