Why did the United States stay in Afghanistan?

President after president has decided to stick it out in a poor landlocked country in the middle of Asia.

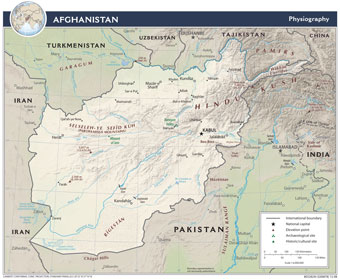

Why has the Afghan war been endless? How was it, as the attacks of September 11 drifted farther and farther away, that president after president decided to stick it out in a poor landlocked country in the middle of Asia?

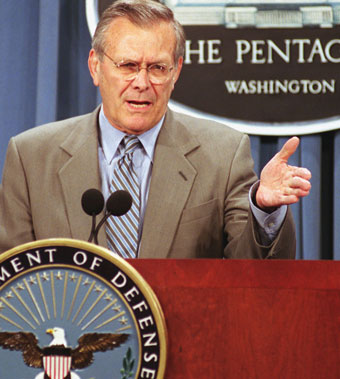

The question is central to our understanding of both the war and the post-September 11 era. As the New York Times editorialized in February 2019: “The failure of American leaders—civilians and generals through three administrations, from the Pentagon to the State Department to Congress and the White House—to develop and pursue a strategy to end the war ought to be studied for generations.”[1] Indeed, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld worried about an exit strategy back in 2001. His instinct was to hit and run. By 2012 plenty of Americans thought that is exactly what should have been done. Yet three U.S. presidents—two of whom were sorely tempted to get out—decided to stay. Rumsfeld himself ended up walking back from his own instincts.

Terrorism and domestic politics explain why they all stayed, assisted by the concern for human freedoms and a reluctance within the military to give up. The attacks of September 11 ignited a fear that presidents could not ignore. Previously a minor irritation, terrorism transformed into a real threat to the United States, with the potential to involve chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons. This was the conundrum of the post-September 11 world. U.S. presidents had to choose between spending resources in places of very low geostrategic value or accepting some unknown risk of terrorist attack.

President George W. Bush never considered declaring victory and going home.

In the early years of the Afghan war, the political atmosphere in the United States was charged with risk of another attack on the homeland. Throughout 2002, various Gallup polls showed between 50 and 85 percent of Americans worried that a terrorist attack on the United States was likely.[2] President George W. Bush never considered declaring victory and going home. He, Secretary of State Colin Powell, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, and Secretary Rumsfeld agreed that the over-riding lesson of the 1990’s experience in Afghanistan was that the United States had created a vacuum by ignoring the country after the fall of the Soviet Union.[3] Bush himself says that an option of “attack, destroy the Taliban, destroy Al Qaeda as best we could and leave” was never appealing because “that would have created a vacuum into which…radicalism could become even stronger.”

The threat receded during Barack Obama’s presidency, yet he, too, could not ignore it. He shelved withdrawal in the run up to the 2009 surge of reinforcements to Afghanistan. Reviewing that history, it seems that full withdrawal was never on the table during the contentious surge debates, even within Obama’s close White House staff. At the outset of the autumn strategy review, President Obama said that the United States would not abandon Afghanistan, a point he later repeated to his National Security Council and to congressional leaders. And in September, Obama and his full NSC unanimously agreed to the same point. During the meeting, even Vice President Joseph Biden, proponent of the famous “CT-Plus” plan to send a smaller force focused on counter-terrorism, denied that an alternative to the surge was to leave Afghanistan.[4] According to the available evidence, at no point during the debate, from early 2009 to the final decision, did any participant advocate full withdrawal.[5]

Withdrawal could have opened the Democrat administration to intense criticism, possibly disturbing Obama’s larger domestic agenda, including saving the economy.

Terrorism was still a palpable threat. Osama bin Laden was still alive. Withdrawal could have opened the Democrat administration to intense criticism, possibly disturbing Obama’s larger domestic agenda, including saving the economy. For the public, although increasing troops came under question in the course of the surge debate, complete withdrawal was not favored. A Gallup poll in early December found that 55 percent of respondents feared that withdrawing troops from Afghanistan would make the United States vulnerable to terrorist attacks.[6]

Only after the surge and the death of bin Laden in May 2011 did a zero option become a serious consideration. Days after bin Laden’s death, a Gallup poll showed that 59 percent of Americans believed the U.S. mission in Afghanistan had been accomplished.[7] “America, it is time to focus on nation building here at home,” Obama announced in his June 2011 address on the drawdown.[8] Nevertheless, it was not until May 2014, after extensive discussions with the military and intelligence assessments, that Obama actually announced a plan to withdraw all military forces from Afghanistan. Only an embassy presence was to remain by the end of 2016.

The intention to get out had met reality and blinked.

But just as the wreck of al-Qa‘eda was finally receding into the distance, the rise of the Islamic State in 2014 resurrected the terrorist threat and its political repercussions. In light of the setbacks of 2015, the intelligence community assessed that if the drawdown went forward on schedule, security could deteriorate to the point that terrorist groups could form a safe haven in Afghanistan. So when confronted with an increased terrorist risk, Obama accepted, with revisions, the requests of General John “Mick” Nicholson and General Joseph Dunford to stay in Afghanistan.[9] The intention to get out had met reality and blinked.

The same fate befell President Donald Trump, the U.S. president with the most disdain for the war in Afghanistan—at least for most of his first term. Trump actually reinforced U.S. troop levels in Afghanistan in 2017, but was never happy with decision. Due to his agitation for an exit, the first substantive talks between the Taliban and the United States commenced in 2018. The result is the closest the United States has come to leaving the war.

Yet Trump has seemed torn between his campaign promise to end endless wars and the possibility of a resurgent terrorist threat, which could harm him politically. He was distinctly non-committal about going to zero in a Fox News interview, in August 2019, stating: “We’re going down to 8,600 and then we’ll make a determination from there,” and then adding that a “high intelligence presence” would stay in the country.[10] And that September, when Taliban leader Maulawi Haybatullah escalated the level of violence, killing one American soldier and wounding many more, Trump assumed he was getting a bad deal and temporarily called off negotiations.[11]

The February 2020 agreement between the United States and the Taliban stipulates that the U.S. military will leave Afghanistan in May 2021. By June 2020, Trump reduced U.S. forces to 8,600, roughly the same number Obama had in place at the end of his term, and they are to go down again to 4-5,000 by the end of October, the lowest number ever. What happens thereafter is unclear. The administration sometimes speaks of a long-term counter-terrorism presence. Like Obama before him, for four years, Trump has not risked a withdrawal that might indict him of permitting a terrorist threat to America.

But Afghanistan’s past may not be its future. Just because the war has been difficult to end, does not mean that will continue to be the case. The constraints of terrorism and public backlash were a feature of American society from 2001 to 2020. That epoch is fading. Great power competition is the rising concern in Washington. With the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the shadow of September 11 may at last recede and terrorism may lose its influence over US policy.

Above all, the coronavirus may be changing America’s outlook on the war. The possible losses from a terrorist attack pale in comparison to the number of Americans who have died from the virus. At the height of the pandemic, nearly as many Americans were dying per day as had died on 9/11. The U.S. economy has also suffered severe damage. To save it, Trump and Congress passed an unprecedented $2 trillion relief package. The pandemic has allegedly enhanced Trump’s interest in getting out of Afghanistan, in order to save money and to prevent troops from dying of coronavirus. In late April, officials reported to the press that Trump reportedly wanted to pull out all U.S. troops lest they be exposed.[12] For the first time since 2001, terrorism is a comparatively minor threat to the United States.

None of that would change the past nineteen years. In another place and time, domestic pressure might have compelled the presidents to withdraw. As we have seen, Afghanistan never curried that kind of opposition. Presidents confronted little popular opposition to staying, however confused Americans were by the war. Not so leaving. A president had to worry about political blowback to a terrorist attack on the homeland. Bush and Obama, if not Trump, also knew they would face disapproval from key political figures and groups when Afghan freedoms were quashed and women were severely oppressed. And any president would be walking out on their own without cover from the generals who were reluctant to lose. The generals could be counted on to obey the decision but not to agree with it. If things went bad, the president could be accused of acting against the advice of the military. Leaving was more politically dangerous than staying. The possibility that a terrorist threat to the United States could once again materialize, especially if the Kabul government fell, always turned out to be too much of a risk. As the conservative Wall Street Journal editorial page succinctly explained in 2019: “There is no domestic political clamor for the U.S. to withdraw all troops, especially with casualties low. The political harm for Mr. Trump would be far greater if a pullout triggered the collapse of the Afghan government and a humanitarian tragedy…The jihadist movement world-wide would declare a great victory.”[13] It was one thing to look years out and coldly promise the United States would leave. It was another to peer over the brink as time drew nigh, see the uncertainties and weigh the political fallout of a terrorist attack, and jump.