Supreme Court appointments in the president’s first year

The vacancy Trump is filling is unprecedented, but there are many and varied stories behind first year nominations

Like nearly everything about the Trump presidency, the timing of his Supreme Court nomination is unprecedented in the modern era. Seven presidents—more than half of those who have served starting with Franklin D. Roosevelt—had the opportunity to nominate a member of the nation’s highest court during their first year in office. But no president in this period had a Supreme Court vacancy waiting for him as he entered the White House, giving him the opportunity to nominate a justice in the first two weeks of his presidency.

As Gerald Ford, “Few appointments a president makes can have as much impact on the future of the country as those to the Supreme Court.” Two of the seven successful first-year appointees by modern presidents were chief justices. Three were women—of the four females who have served among the 112 total justices. One was the first Latina justice.

Reasons vary for why court vacancies occur so early in a presidential term. In Trump’s case, the seat of the late Justice Antonin Scalia remained open when the Republican Senate majority, in another unprecedented act, refused to give President Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick Garland a hearing, much less a confirmation vote. Garland’s nomination expired with the start of the new Congress in early January 2017, almost eleven months after Scalia’s unexpected death. The GOP strategy had worked; a Republican regained the White House and the chance to name a conservative to a court often evenly divided on the most important issues.

Sometimes the reason for a first-year vacancy is purely coincidental, notably the sudden death of Chief Justice Fred Vinson in 1953 and Justice Abe Fortas’s forced resignation over financial improprieties in 1969. Occasionally a new president’s whim creates a vacancy, as when Lyndon Johnson asked Arthur Goldberg to vacate his seat on the bench in 1965 to become U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Goldberg did not want to leave the Supreme Court, but, as he said regretfully when asked why he did so, “Have you ever had your arm twisted by Lyndon Johnson?” Moving Goldberg to New York gave LBJ the chance to nominate his friend Fortas to the court.

The retirement of a justice who waits for a president of his party or ideology to occupy the White House presents a more predictable pattern. Justice Potter Stewart, appointed by Republican president Dwight Eisenhower, retired in 1981, shortly after Ronald Reagan, another Republican, became president. Justice Bryon White, a Democrat nominated by John F. Kennedy, left when Democrat Bill Clinton took office in 1993. Although Justice David Souter had been placed on the court by Republican President George H. W. Bush, he frequently voted with liberal colleagues during his nearly 20 years on the bench and stepped down in 2009 after Democrat Barack Obama swept to victory. All three justices also knew that the president’s party had a Senate majority that made confirmation of a like-minded successor probable.

Occasionally, other circumstances create a first-year vacancy. Republican Justice Owen Roberts became so uncomfortable with the judicial activism of FDR’s appointees that he retired during the Truman administration. The new president, who had assumed the office after Roosevelt’s death, made a bi-partisan gesture by nominating his trusted friend from their Senate days, Republican Harold Burton, to replace Roberts. Chief Justice Earl Warren, the former Republican governor of California, who, although placed on the court by Eisenhower, had led a liberal judicial revolution, told Lyndon Johnson in the summer of 1968 that he would like to retire. Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans deployed the filibuster to deny LBJ’s promotion of Justice Fortas to chief justice in 1968. Warren stayed on for another term but reluctantly stepped down in the first year of Richard Nixon’s presidency.

Because most justices in the modern era leave the court at the end of its term in early summer, even those who retire in an elected president’s first year generally do so after he has been in office for at least a half-year. The unexpected openings created by Vinson’s death and Fortas’s resignation occurred in September and May, respectively. From Truman through Obama, no new president faced the consequential decision of whom to name to the Supreme Court until well after the inauguration. Truman had three months after FDR’s death elevated him to the presidency to settle into the White House before Roberts retired. World War II still raged in the Pacific Theater, and Truman thought it wise to exemplify bipartisanship by nominating Burton. In subsequent years, he maintained this pattern of naming long-time Washington friends for all four of his Supreme Court nominations, although his other nominees were Democrats.

Following its custom, the Senate voted unanimously for one of its own to cross 1st Street to sit in the “Marble Temple.” Once on the court, Burton tended to practice judicial restraint. Although he usually disagreed with the more liberal wing of the court, he brought much-needed civility to its debates. He was not possessed of a superior intellect, however, and Court scholars have typically judged him as a failed justice.

When Chief Justice Vinson, another Truman friend and appointee, succumbed to a heart attack eight months after President Eisenhower’s 1953 inauguration, Ike turned to a rival for the 1952 Republican nomination, Earl Warren, who had no judicial experience. He had been a county prosecutor and the California attorney general before becoming governor of his state. He had also occupied the vice-presidential slot on the unsuccessful Republican presidential ticket with Thomas Dewey in 1948.

Eisenhower had spoken to Warren about the possibility of a Supreme Court nomination prior to Vinson’s death; Ike approved of the congenial governor’s “basic philosophy,” “high ideals,” and “common sense.” The Senate confirmed the appointment by a unanimous voice vote, despite a nearly even split between Democrats and Republicans in the chamber. Although Eisenhower believed he had named a moderate to lead the court, Warren wrought a liberal revolution in civil rights and liberties that prompted “Impeach Earl Warren” signs to spring up throughout the conservative hinterlands. He was anathema in the South after his landmark Brown v. Board of Education rulings in 1954 and 1955, which ordered public schools to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” His leadership in broadening criminal rights provoked an equally vehement backlash. Warren’s legacy continues to stir battles on the bench and in judicial appointments four decades later. Scholars rank him among the court’s “greats.”

Arthur Goldberg, who was appointed by President Kennedy, had not even served three years on the court when President Johnson named him U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. LBJ was determined to place Fortas, his old friend and legal advisor, on the high court. If no opening occurred naturally, why not create one? Goldberg held what was then known as the court’s “Jewish seat,” previously occupied by Benjamin Cardozo and Felix Frankfurter. Johnson would simply trade Fortas, also Jewish, for Goldberg and perhaps garner credit among Jewish voters for choosing one of their co-religionists to represent the United States at the U.N.

Fortas expressed unease with his nomination, preferring both his informal advisory role to the president and a lucrative law practice. He occasionally accepted pro bono assignments, as when he argued Gideon v. Wainwright before the Warren Court, winning the right for indigents to receive free legal counsel from states in non-capital criminal cases.

Only three conservative Republican senators (out of 32) dissented from the superbly qualified Fortas’s nomination as associate justice. In little more than three years on the Court, he distinguished himself with landmark liberal opinions, especially involving the juvenile justice process. And he famously wrote in favor of free speech for students, arguing that they do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the school house gate.” Despite his truncated tenure and reason for leaving, Fortas is ranked by scholars as a “near great” justice.

When LBJ’s effort to promote Fortas to chief justice failed in 1968 and he resigned as associate justice in 1969, the next president had two positions to fill on the Court: the one abandoned by Fortas and the chief justiceship, which Warren had chosen to resign. Nixon had made the Warren Court’s liberal rulings a prominent issue in the 1968 campaign, promising to name “law and order” justices. The new president also was looking for a way to advance the Republican Party’s rising fortunes in the heretofore solidly Democratic South. His first two nominees to fill Fortas’s seat, Clement Haynsworth of South Carolina and G. Harrold Carswell of Florida, were rejected by the Democratic Senate, in retaliation for Fortas’s defeat the previous year and, in Carswell’s case, because of a racist past. After publicly branding the Democratic Party hostile to southerners, Nixon nominated Harry Blackmun of Minnesota, who was easily confirmed but not until well into the second year of Nixon’s presidency.

For chief justice, Nixon turned to Warren Burger, a conservative appeals court judge, who had a middling résumé but certainly looked and sounded the part, as if central casting had hired an actor with chiseled features, a shock of thick white hair, and a basso profondo voice to preside in the majestic courtroom. Despite the Democrats 57-43 majority, the Senate approved Burger’s nomination with only a trio of dissenters. The new chief justice went on to create a legacy that was more related to preserving the court’s building and its history than to landmark judicial decisions. He disappointed Nixon’s supporters by not leading a full roll-back of Warren era rulings and by writing the unanimous opinion in U.S. v. Nixon, which forced the president to release the Watergate tapes and ultimately resign from his scandal-ridden presidency.

While visiting Arizona in the late 1970s, Burger met an impressive lawyer and politician, Sandra Day O’Connor. Several years later he escorted her down the marble steps of the Supreme Court as its newest member. During the 1980 presidential campaign, Ronald Reagan had developed a “gender gap” when polls indicated that women supported him at a lower rate than men did. Although Reagan staunchly opposed affirmative action policies, he announced during the campaign that one of his nominations to the Supreme Court would be a qualified woman—the first to serve on the tribunal.

Justice Stewart’s retirement at the end of the Court’s term in the summer of 1981 gave Reagan the opportunity to make good on his promise. Stewart was a moderate conservative, and Reagan’s advisors found the perfect replacement for him in O’Connor, who was then serving as an Arizona Court of Appeals judge. With the Senate now in Republican hands, thanks to Reagan’s coattails in the election, the first woman nominated for the Supreme Court sailed through unanimously.

In her near-quarter-century as associate justice, O’Connor became an icon for women around the world and made her mark with a moderate jurisprudence that vaulted her into the decisive “swing seat” on the closely divided Court. Like her mentor, Justice Lewis Powell, she would sometimes provide the deciding vote for the liberal bloc and at other times for the conservative wing. She voted nearly always for women’s rights in abortion, affirmative action, employee benefits, military academy admissions, and sexual harassment cases.

Democrat-appointed justices who did not want to be replaced by a Republican president had to wait through the twelve years of the Reagan and Bush administrations before contemplating retirement. Byron White, a Kennedy nominee who reflected the president’s moderate liberalism, had completed his third decade on the high court when he announced he would retire at the end of the term in June 1993. Newly elected Democrat Bill Clinton had his first opportunity to name a justice.

Initially, Clinton considered a politician in the Warren mold. When that plan foundered, he turned to federal appellate judge Stephen Breyer. But he was recovering from a bike accident, and his interview with the president went poorly. Clinton then reached out to Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the District of Columbia Circuit, and she aced her interview with an inspirational narrative of how she overcame life’s tragedies and gender discrimination. In one of the last uncontested Supreme Court nominations, Ginsburg swept to confirmation with only three Republican nay votes in the Democrat-controlled Senate. Just the second woman on the Court, she has served nearly a quarter-century as a reliable liberal vote and leader for gender equality, as she was earlier in her career.

After waiting out George W. Bush’s two terms as president, Justice Souter, an introverted New Englander who had never been comfortable in Washington, happily retired from the court in 2009, President Obama’s initial year. The first African-American president made history by selecting the first Latina justice. Sonia Sotomayor’s stellar education credentials and service on both federal trial and appellate courts, with appointments from Republican and Democrat presidents, made her an obvious nominee, especially to reward the 67 percent of Hispanics who had voted for Obama in 2008. The era of bi-partisan support for Supreme Court nominees had ended, however, and only 9 of 40 GOP senators supported Obama’s first nominee.

An active questioner at oral argument, Sotomayor has formed a solid liberal bloc with Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, and Obama’s second appointee Elena Kagan. When they are able to attract swing voter Justice Anthony Kennedy, a majority supports abortion rights, affirmative action, marriage equality, and church–state separation.

As Henry J. Abraham has observed, the historical criteria for Supreme Court nominees include merit, political and ideological compatibility, representative characteristics (religion, race, gender, and ethnicity), and personal or political friendship. Modern Supreme Court appointments in presidents’ first years have reflected all of those considerations. Except for Truman’s nomination of his friend Burton (a partisan anomaly during World War II), all recent nominees, like those of most presidents throughout history, appeared to share a political and ideological kinship with the chief executive who named them. But their appointing presidents’ ideological expectations were unmet by Warren, O’Connor, and, to some extent, Burger. Across the entire spectrum of appointment history, only about one-fifth of justices have disappointed the president who appointed them. In the cases of Warren and Burger, Eisenhower and Nixon misjudged the effects their chief justiceships would have. Or, as with O’Connor, another factor (in this case, gender) outweighed her moderation in Reagan’s eyes. Ginsburg and Sotomayor combined both representative characteristics and ideological compatibility with Clinton and Obama. As with geography and religion in an earlier era, nominees’ gender and ethnicity have sometimes guided recent first-year presidents in their effort to reward constituencies who helped propel them to office or who, they hoped, would help to reelect them.

In addition to bipartisanship, friendship determined Truman’s court appointments, trumping merit. Ideology was responsible for the same result in Nixon’s selection of Burger. LBJ’s reliance on his friend Fortas to fill the Goldberg seat did not dilute merit as a criterion. Unfortunately, however, Fortas failed to overcome cronyism in favor of judicial ethics. Four other first-year appointees (Warren, O’Connor, Ginsburg, and Sotomayor) were also highly qualified by virtue of education, experience, and intellect. They maintained their integrity on the bench.

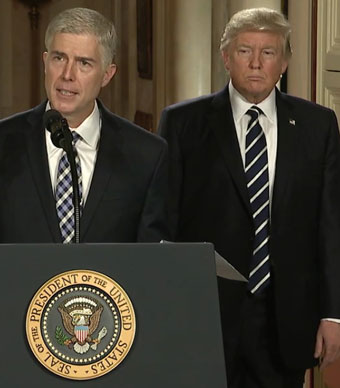

Trump’s choice of Judge Neil Gorsuch, of the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, fulfills both the merit and ideological compatibility criteria of selection. Suggested and endorsed by the conservative Federalist Society during the 2016 presidential campaign, Gorsuch believes in following the framers’ intentions when interpreting the Constitution and laws and applying the meaning of their words at the time they were written. He comports with Candidate Trump’s litmus test for Supreme Court service: namely, overturning Roe v. Wade and upholding a broad interpretation of 2nd Amendment gun rights.

The Senate’s confirmation of Judge Gorsuch now depends on a number of political factors. Republicans implemented a new protocol in denying Obama’s nomination to fill Scalia’s seat, one that the Democrats will not quickly forget, as they did not forget the 1968 filibuster used to block Fortas when they refused to confirm Nixon’s 1969 nominations of Haynsworth and Carswell. (The question will remain, how late in a term may an incumbent president replace a Supreme Court justice? While a senator, Democrat Joe Biden, suggested the one-year rule.) A filibuster, which McConnell has respected as a moderating influence on the upper house, may be used by the minority party to require 60 votes to confirm Gorsuch. Leader McConnell and his Republican colleagues could go “nuclear” and eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations, as the Democrats did under their leader Harry Reid for lower federal court judgeships. If so, only a simple majority would be required to confirm Trump’s nominee.

Another political roadblock could insert itself into the Gorsuch nomination battle, however. It dates from the blockage of Reagan nominee Robert Bork by a Democratic Senate majority in 1987. The seat vacated by “swing vote” Lewis Powell (a moderate Virginian who sometimes voted with liberal colleagues and at other times with conservatives) ignited a bitter battle between Reagan supporters who wanted to turn the court to the right and Democrats, led by Senator Edward Kennedy, who argued that “Robert Bork’s America” would be a flashback to a time in our history when civil rights and liberties were not paramount.

Scalia’s vote was typically on the conservative side of the judicial spectrum, with some notable exceptions, in search and seizure and flag-burning cases, for example. With eight members, the Supreme Court is now narrowly split, sometimes tied, on such nettlesome issues as abortion, immigration, affirmative action, death penalty, gay rights, guns, health care, and campaign finance. In the Bork mold, Trump’s nominee is a scholar of the law and has written numerous books and articles on legal theory. He is undeniably qualified for a seat on the nation’s highest court by virtue of his intellect, education, and experience. A “stealth nominee,” like David Souter, he is not. His very record will cause Democrats to mount severe opposition in order to prevent the 49-year-old Gorsuch from shaping landmark decisions for the next three or four decades.

The Founding Fathers did not want to place sole appointment power for the Supreme Court in Congress because they thought its members too filled with political “intrigue.” Yet judicial nominations have always been prone to politics, especially as soon as our Founders split into two warring partisan camps. Alexander Hamilton hoped that integrity and knowledge of the law would trump political considerations in Supreme Court nominations. On that basis both Merrick Garland and Neil Gorsuch are more than qualified, and it is a shame that both could not serve in the “Marble Temple” on Capitol Hill.

When Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes laid the Supreme Court’s cornerstone in the midst of the Great Depression, he declared, “Our republic endures and this is the symbol of its faith.” Fortunately, most of the first-year appointments in the past seven decades have enhanced that symbol with their meritorious service to our nation on its highest court.