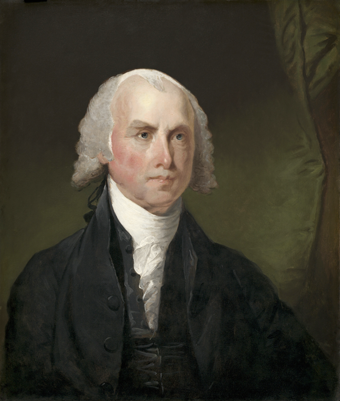

James and the giant impeachment

Madison and other Founders explored the role of impeachment in the system of checks and balances

Read the full story at The Hill

James Madison observed, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” and that to counter less-than-angelic human nature “you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.” He and his fellow Founders at the 1787 Philadelphia Constitutional Convention searched for a delicate balance between establishing a regime that was strong enough to cure the republic’s ills without violating liberty.

The creation of the presidency and Supreme Court distinguished the new Constitution from the nation’s first governing document (the Articles of Confederation) that established only a Congress. Checking and balancing these three separate, yet intertwined, branches of the federal government became the Framers’ key goal. Devotees of Newtonian physics, they searched for a governing system whose movements and gravitational pulls would function like “a machine that would go of itself.”

Yet they had only recently broken the bonds of arbitrary monarchical rule in the bloody Revolutionary War, so they had to find ways of mitigating the possibility that “enlightened statesmen may not always be at the helm,” as Madison expressed his fear. In his blueprint for the Philadelphia Convention, he proposed that the executive could be removed and disqualified from holding future office after impeachment and conviction for “malpractice or neglect of duty.” Madison borrowed from the British parliamentary practice of removing the monarch’s ministers for subverting the state or violating the rule of law.

Another Virginian, George Mason, argued for “some mode of displacing” the executive, without reducing him to a “mere creature of the legislature.” He worried that a president might gain office by corrupt means — bribing the Electoral College, for example. “Shall a man who has practiced corruption, and by that means procured his appointment in the first instance, … escape punishment by repeating his guilt?”

Madison agreed. Waiting to turn a corrupt president out of office by defeating him at the ballot box was insufficient. Like all of the Founders, who worried about improper influence from outside the nascent country, Madison warned that the president might even “betray his trust to foreign powers.”