About this episode

January 27, 2017

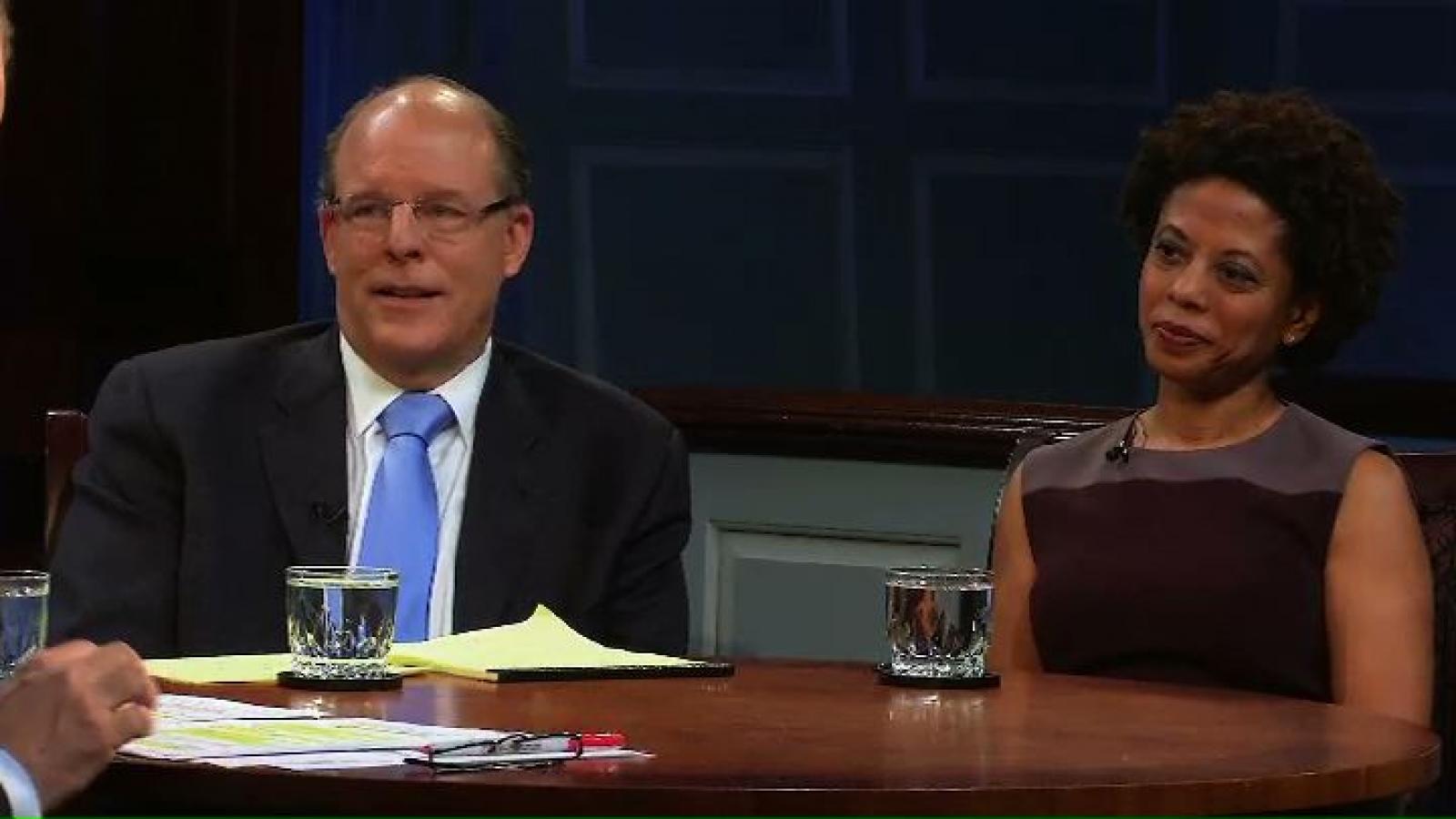

Melody Barnes and Peter Wehner

How will the election of Donald Trump affect Americans' pursuit of happiness? Our First Year Project asks two experienced policy practitioners to see what actions might lie ahead. Melody Barnes was director of the Domestic Policy Council early in the Obama administration, and an advisor during his 2008 presidential campaign. She was chief counsel to Senator Ted Kennedy on the Senate Judiciary Committee for five years. Today, she's a senior fellow here at the Miller Center. Peter Wehner was in three Republican presidential administrations: George W. Bush, George H. W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan. He was a speechwriter in the Reagan and George W. administrations and became head of the White House Office of Strategic Initiatives in 2002. Today, he is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, DC.

Jobs and Economy

First Year 2017: Donald Trump and the American Dream

Transcript

It’s about history, policy, and impact. A new perspective on current affairs, bringing experience, insight, civility and scholarship to the urgent issues today. It’s about our past, present, and future. Your host: Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist Doug Blackmon. From the University of Virginia's Miller Center, this is American Forum.

Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I'm Doug Blackmon. The 2016 presidential campaign was not really about issues. Instead, it revolved around anxiety. Anxiety about the reliability and trustworthiness of the two major nominees. Anxiety about not just the future of the country, but whether there would be a future. Whether the economic turnaround was real, whether our schools are failing, our retirement safe. Is the government getting in the way of good things rather than making more good things possible? Whether our children and their children will be able to find work that is rewarding and stable. Ultimately, it was anxiety about the American dream, about whether it's slipping away, and which candidate Americans believed could save it. In this episode, we continue American Forum's special series of programs growing out of our First Year Project. It's the culmination of months of effort at the Miller Center to identify the most urgent issues that would face whomever became president in 2017, assemble non-partisan groups of experts to study them, and to give practical advice for moving the country forward. So, the big question in this episode is can newly inaugurated President Trump restore the American dream? Or does it really even need to be restored? Is it possible, somewhere in all the division and anxiety, to identify places where opposing sides can find common ground? What's going to happen on domestic issues like tax reform, child care, job growth, infrastructure, and education, all essential elements of the American dream? And finally, how much can happen in the critical first year of the Trump administration, when new presidents often have their greatest level of political capital and public popularity? Our guests today are two former White House aides, one a liberal Democrat and the other a conservative Republican, both steeped in policy debates related to the American dream. Melody Barnes was director of the Domestic Policy Council early in the Obama administration, and an advisor during his 2008 presidential campaign. She was chief counsel to Senator Ted Kennedy on the Senate Judiciary Committee for five years. Today, she's a senior fellow here at the Miller Center. Peter Wehner was in three Republican presidential administrations: George W. Bush, George H. W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan. He was a speechwriter in the Reagan and George W. administrations and became head of the White House Office of Strategic Initiatives in 2002. Today, he is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. Thank you both for joining us.

Peter Wehner: Pleasure to be here.

Barnes: [Great?].

Wehner: Thanks.

Barnes: Thank you.

Blackmon: Over the last 50 years, one of the biggest themes in American politics and governance has been this question of whether the government is the enemy. We can go back to Ronald Reagan's first inaugural—and said very clearly that government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem. But Peter, you—as somebody who—you're not a Trump guy by any stretch of the imagination. But you've been involved in these administrations, you've been part of this process. In the end, is that still the right way to look at these situations? Is the government the problem? And is now a lack of faith in the government its own extraordinary problem?

Wehner: Yeah. I don't think it's the right way to look at it, in terms of the government being the enemy. I've never been particularly fond of that formulation, because you can't run a country without a government. You know, the traditional divide here is between big government and small government. Big government, from the liberal perspective, small government from the conservative perspective. I'm not even sure that that's the right way to look at it. I think the key here is effective government—is essentially what works. Welfare reform, which I think—the 1996 welfare reform legislation was one of the most effective social policy legislations in the last 50 years. But we actually spent more on welfare after that was done. What was important was to get the incentives right. And we did, so you had a huge drop not only in the welfare rolls—60 percent drop within a half a decade—but the condition of the poor actually got better. Then you take crime: you had a huge drop in crime. From 1993, violent crime's been cut in half. That's not because government got smaller. It's because government got smarter in all sorts of ways—of policing techniques, incarceration, private security, and that kind of thing. And the earned income tax credit, which came into being during the Ford administration, is one of the great anti-poverty, pro-work programs. So, I think what we need to do is to get into a mindset of really what works.

Blackmon: And so, what would you say to the proposition that this is one of the—that this, perhaps, is a major problem, that the active deterioration and the encouragement of this deteriorating view of whether government is important, whether it's good for the country or not—to what degree is that a liability to governance now, regard—you know, and would have been for any president, but particularly for President Trump?

Barnes: I think it's a significant problem. And it's interesting, I agree with a lot of what Pete just said. Actually could hear the lyrics to Hamilton, the musical, going through my head (laughter) as he was talking a little bit. I would use different examples, and I think probably that shows some of our ideological differences. But I agree with a lot of what he's saying, and I think, to your question, that this is a significant problem. And the idea that we cannot trust or believe in government as an institution starts to fracture some of what allows us to come together as a country. Also, it affects the way that people see policy makers, policy-making, and believing that there is no art or science to any of it, and trust in those that they have elected to lead. Maybe the—not their elected representative, but elected representatives in general. And I think that that is a significant problem. I think that it's critical that we start to address this problem with—a lack of trust in the institution of government, institutional distrust in general, the media, and find ways that we can work together. But one of my deep concerns is that we have a president who made a lot of promises during the campaign that I think many—and not just Democrats, but Republicans—don't believe can be met. And that, I believe, will continue a process of ultimately—whether it's two years or four years from now, or six—a number of members of American society thinking government actually really just doesn't work.

Blackmon: Well, we seem to also have one newish dimension that I think is a bit different, even from the Tea Party phenomenon of 2010 to—we've now moved to another phase of this process—is this even more fundamental inability to agree on very basic pieces of information. How does it come to pass that there could be so fundamental a disagreement about the most elementary facts? And then, how is it that advisor—you know, wise advisors like the two of you can advocate somehow for a return to fact?

Wehner: What you're getting is a kind of tribalism in politics, right? Our side and their side, and these sort of silos that people live in. So, you live in these hermetically sealed-off worlds in which all you do is listen to people who have the same opinion as you. And you've got people who now have the capacity to interject all sorts of conspiracy theories and lies and misinformation out there [and the?] people latch onto it. [You know?], Daniel Patrick Moynihan years ago was a great Democratic senator and scholar—said that people are entitled to their own opinion, but they're not entitled to their own set of facts.

Barnes: What is also happening, though, which I think is reassuring—and the question is whether or not this is going to take root, take hold, is that there is a movement afoot, coming out of Washington, to focus on evidence-based policy-making. And, in fact, in a bipartisan fashion, in the course of the past 18 months or so, Speaker Ryan and Senator Patty Murray of Washington came together to pass legislation to create a commission to focus on data and evidence and policy-making. And it's a bipartisan commission. I know some of the people on there who are terrific, Republicans and Democrats. And the first thing they're trying to do is say how do we make data that comes out of the federal government more accessible to researchers and to analysts and others? Once we make that data more accessible to them, how do we find ways to look across government and to better aggregate that data so that we can look—we can do slices across programs to better understand what's happening in the American populous. How do we do all of that in a way that protects people's privacy? And then, how do we find ways that we can build a more evidence-based culture inside of policy-making that also isn't, you know, off-the-charts expensive. I mean, we know randomized control trials and all the things that policy wonks love are extremely expensive. But how do we work from there down so that people in their communities who are trying to do good work can also better evaluate what they're doing, and that we all have access to that? And from there, we can make some decisions about how we should govern. I mean, I think that is a good place to start, because, as John Bridgeland and I have written about, right now, sitting inside the federal government, we don't have the necessary architecture so that we can make better policy decisions based on data and evidence, which in theory, at least, should help us to navigate some of the in your corners partisan divide.

Wehner: One of the solutions—and I think Melody was getting to this with the bipartisanship, but I'll speak sort of directly to what I think it requires. It requires people of standing, including presidents, to tell people in their own movement, in their own party, certain facts they have to accept that are uncomfortable. It doesn't work if Barack Obama is telling conservative Republicans what they have to believe or George W. Bush is telling liberal Democrats what they have to believe, that—it doesn't work that way. There—people aren't attuned to it. They're going to say, “That person is an opponent. That person is an enemy, and I reject it.” But what you have to do, and there's no—I don't have an easy solution for it, but you have to get people who have respect within that party or within that intellectual movement to be able to begin to challenge more people that are part of that movement or part of that party. And if that doesn't happen, given the environment that we live in, this is going to just continue to accelerate.

Blackmon: Most of what we've been talking about here is kind of trying to work through the frustration of the inability to arrive at agreement on facts. Let's see if we can shift somehow into more of a discussion of what we think might happen in the current environment that we're in, where might things go in this first year of the Trump presidency as it relates to some of these domestic policy issues. I mean, in the range of things that have been talked about—I mean, President Trump, while a lot of his policies—it's not entirely clear what they're going to be, but the—on infrastructure, there's been some specificity about that, the idea of an infrastructure bank that would then be used to leverage up to a trillion dollars of total funding for infrastructure projects, and that that would also have job growth and broader economic impact. That's one that's actually very similar to things that the Obama administration pushed for a long time and that conventional Republicans were very opposed to. Nonetheless, there's—that sounds like a point of agreement, that, you know, that there's some agreement between at least two factions in this picture over the value of a plan like that. Is there a meeting point in there somewhere?

Barnes: Maybe. (laughter) You’re exactly right in your characterization of something that the president pushed for, you know, President Clinton pushed for in terms of infrastructure bank—and, in fact, linking that to repatriation that would happen during a tax reform process. So, those things are true. I think, in part, there will need to be a decision made by Democrats—the degree to which, after—well, recognizing that there is now President Trump, that they want to work with this administration. I mean, I think certainly coming right after the election, there were a number of people who were so intensely frustrated with that outcome that the idea of putting wins on the table with this White House was something that they couldn't imagine. You know, I think recognizing that the nation moves forward, that there are problems that need to be solved and infrastructure can solve helps solve a jobs-related problem, it can help address some of the concerns in the private sector in terms of the infrastructure that's needed with our ports, with our bridges, with highways, etc., to make that work more effectively. And that is—it is stimulative or could be stimulative even given where we are in our economy right now in nature that there could be a movement to work with this White House on that.

Blackmon: What would you say to the Democratic congressman or the Democratic leadership that said to—you know, there's an overture from the Trump White House to say, “Look, some of these Republicans are resisting my desire to do this thing that looks a lot like what you wanted to do. Why don't you work with us on this for the good of the people?” What would you say to the Democratic leader who said, “I'm not working with you! You know, your people, those guys over there who are in league with you resisted everything we tried to do, so we're not going to help you on anything. And meanwhile, you're trying to dismantle our most important signature objectives.” I mean, is there any—is there a way beyond that impasse?

Wehner: I—sure, I mean, theoretically there is, and (laughter) even practically there is. You know, one of the first calls, maybe the first call that George W. Bush did after a very divisive 2000 election was to George Miller and Ted Kennedy to talk about No Child Left Behind. And the interesting thing about President Trump is he's actually ideologically probably more flexible than most of the people he would have run against. He was a liberal Democrat for many years. He was a Democrat for most of the 2000s. And he has talked about policies more that liberals have embraced than conservatives over the years. So, there's a kind of ideological flexibility. The complicating factor here is his temperamental instability.

Blackmon: But doesn't all of that suggest that what highly responsible, empirically grounded policy theorists and activists should be doing would be encouraging some sort of alliance within the Congress? That the idea that some group of Democrats and some group of Republicans should be working to come together on some agenda that actually involves the kind of give-and-take compromise that hasn't been there for a long time and then be presenting that as—say, “If you want immigration or major border control changes, then that can only occur, Mr. President, if you go along with a broad package of other things that have been agreed to by Democrats and Republicans in the Congress”? I mean, is that the kind of approach—

Barnes: That certainly could happen. I mean, if you imagine a certain set of actors—you know, Chuck Schumer, Mitch McConnell, they've known each other for a long time. You know, they both know how to cut deals. You know, Speaker Ryan, Reince Priebus. I mean, you've got people, including the new head of legislative affairs in the White House—you've got people who understand how this—how that process works.

Blackmon: But Peter, is something like that something that—whatever it means when one says conventional Republicans, whatever that means—but is something like the scenario that I put—that I just mapped out, which is essentially congressional Republicans, more traditional congressional Republicans, trying to effectively take control of the Republican legislative agenda and make the president the weaker party, the weaker player in that sequence? Is that something that Republicans would seriously think about? Like you?

Wehner: Well, certainly it is something I would think about, yeah. (laughter) Absolutely. I think it's something that—frankly, that the Republicans on the Hill are thinking about if you talk to them privately. I think that their hope, very much, is that Donald Trump's—is contained on Twitter, as problematic as that can be, but he leaves the governing to the adults.

Blackmon: But what I'm trying to figure out is, is there some path that the American people, that responsible citizens, that engaged Americans—can be looking for some signs of, okay, here's a way that even somebody who was energetically anti-Trump on the Republican side could see, yes, a possible path forward? And is that a path that somebody like Melody could also see some virtue in? I mean, the—we talked about infrastructure. Are there other domestic policy issues that offer some kind of—is education one? That—

Barnes: Well, I was actually going to mention tax reform, because there has been—one, because it's been on the top of the list and something that has been talked about since the election as a top priority for President Trump. Secondly, because particularly with corporate tax reform, there's been some circling around that for quite some time. And what—again, what the details look like will matter. But I think that's a place where we could see some movement. And there are certainly things that sit inside tax reform. And even when they get to—beyond corporate, and—there's some sense that they may go to personal reform later down the road, and things that I think that we agree on. And, in fact, you see other Republicans—and a history of bipartisan support around the earned income tax credit, for example, or the—and the child tax credit and expansions there, which also address issues for the working poor and for others. So, that might be an area where we could see some potential movement.

Wehner: So, the challenge here isn't the same as it would be if, say, Ted Cruz had been elected president, right? If Ted Cruz had been elected president—that was a person who's much more ideological. Donald Trump is a dealmaker. That is a characteristic that he's had. He's not an ideologue by any means. He's ideologically and philosophically rootless. Now, that gives the capacity to make a kind of agreement. His whole life has really, I think, been characterized by making deals. And so, he may well want to do an agreement with Chuck Schumer. He may well like Chuck Schumer more than he likes Mitch McConnell or Paul Ryan. I don't think that there's going to be a kind of ideological loggerhead that you might have gotten with other Republicans or with Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton.

Blackmon: So, Peter, if there were one thing that you were going to ask President Trump to do, specifically, to create some sort of bridge between himself and you and Republicans, the kinds of Republicans you represent—I mean, he clearly needs that kind of repair. From a conservative agenda perspective, he needs to bridge the polarization just between himself and his supporters and people like you. What's the one thing he could do in the next year to stabilize and—to reassure you and stabilize that alliance?

Wehner: In terms of legislation and where to go, I mean, I would say kind of pick 'em. There are a whole series of issues that he could do. Tax reform would be one thing. A responsible immigration reform would be another. And education would be a third. I don't think he has to pass fantastically ambitious legislation. I'm not even sure that's what's necessary now. It may be that we're at a state in our politics where kind of incremental reforms were—are necessary. I will say that it would be, from my perspective, helpful if he were to back away from his protectionism, which I think can lead to a global recession if he really pushes this thing beyond the rhetoric.

Barnes: Throughout the campaign there were comments about being a law and order president, which stem back to and harken back to other dog whistles from the past that have unleashed really dangerous and undermining policies on low income communities, particularly communities of color. And I think he can do things that reflect a new way of looking at addressing crime and crime policy that are, in fact, related to data and evidence that begin to roll back or continue to roll back the mass incarceration of now millions and millions of individuals, more than most in the developed world, many who are people of color, many for minor crimes, that are fracturing families. And that would be an important step forward, along with issues that pertain to workforce training and education. What he could also do, which I don't see him doing, but appropriate ways of addressing issues with the Affordable Care Act that don't prevent millions of people from losing their health care. Those are the kinds of things that he could do that would start to let people believe that, in fact, he would be the president for all Americans.

Blackmon: These are long days ahead. (laughs) Pete Wehner, Melody Barnes, thank you both for being here.

Wehner: Thanks.

Blackmon: A reminder before we go that American Forum is about the presidency, about how great leaders make decisions, how average leaders make good decisions, and how all of us can advocate for what we believe and resist what we oppose, but to do it in a way that still respects just how effectively our political system has ultimately worked for 200 years. We all have a patriotic duty to share our views but to never give up on our fellow citizens, no matter how mad they make us. (laughter) If you'd like to join our conversation about these or any of the issues facing our new president, go to the Miller Center Facebook page. Visit MillerCenter.org or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @DouglasBlackmon. Melody Barnes is @MelodyCBarnes. And Peter Wehner is @Peter_Wehner. In the coming weeks, American Forum will continue its focus on the first year of the Trump presidency, with episodes looking at immigration, broken government, as well as a look back at the first years of key presidencies in our history. Guests will include Washington Post columnist E. J. Dionne, famed American historians Gary Gallagher and Brian Balogh, host of NPR's BackStory. For more about our First Year Project, go to the website, FirstYear27.org. I'm Doug Blackmon. Thanks again to our guests, see you next week.