About this episode

April 16, 2017

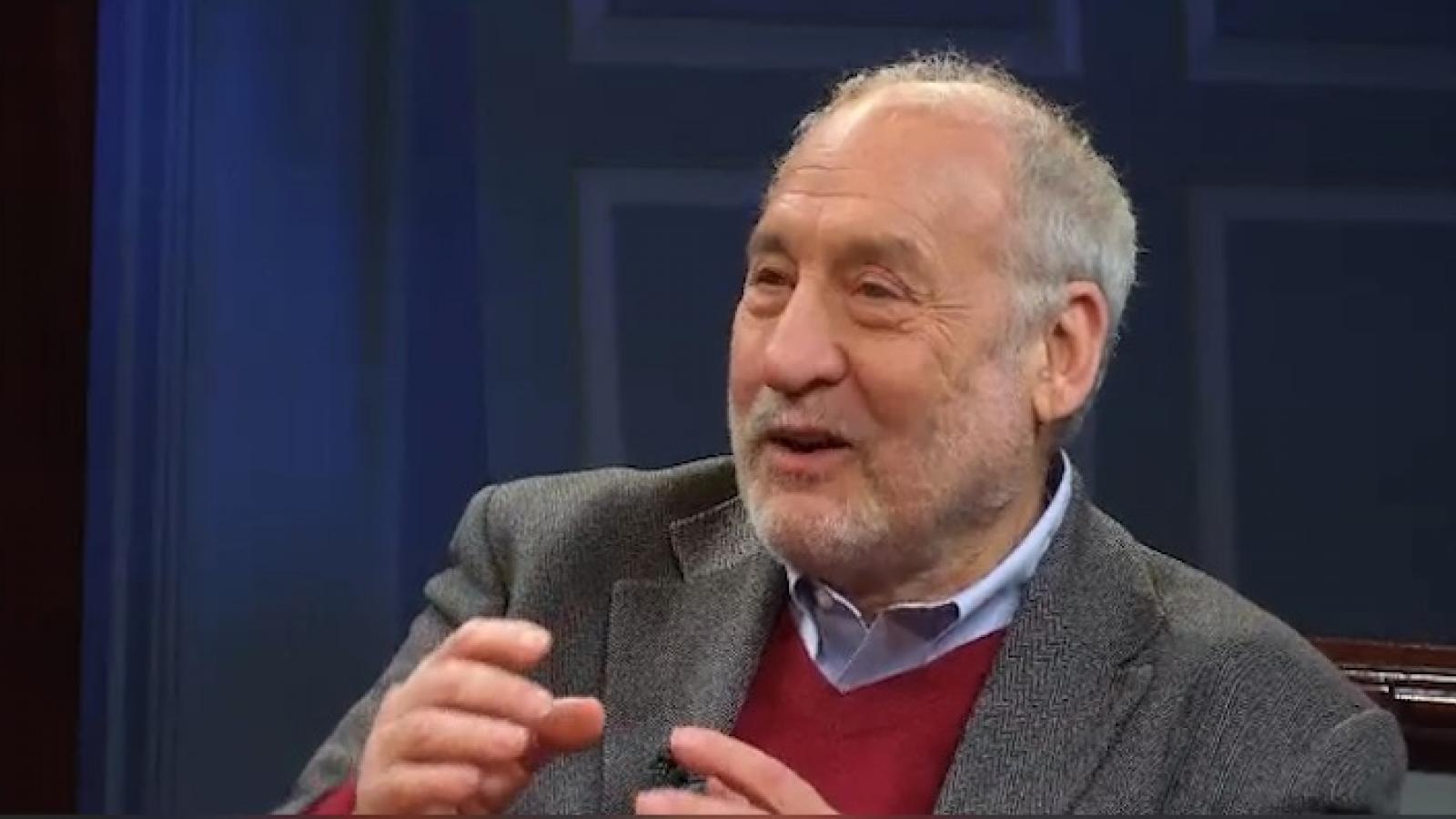

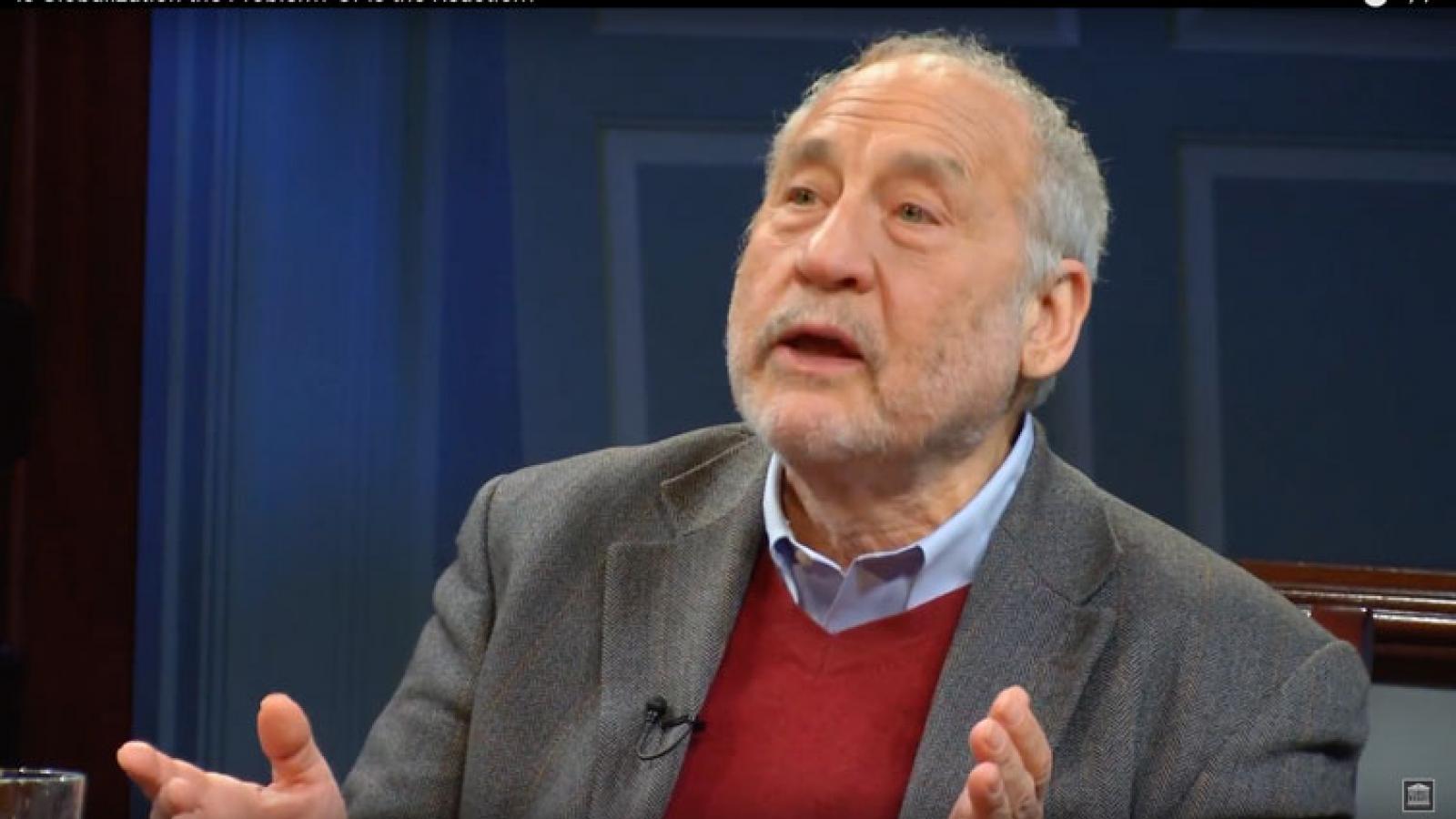

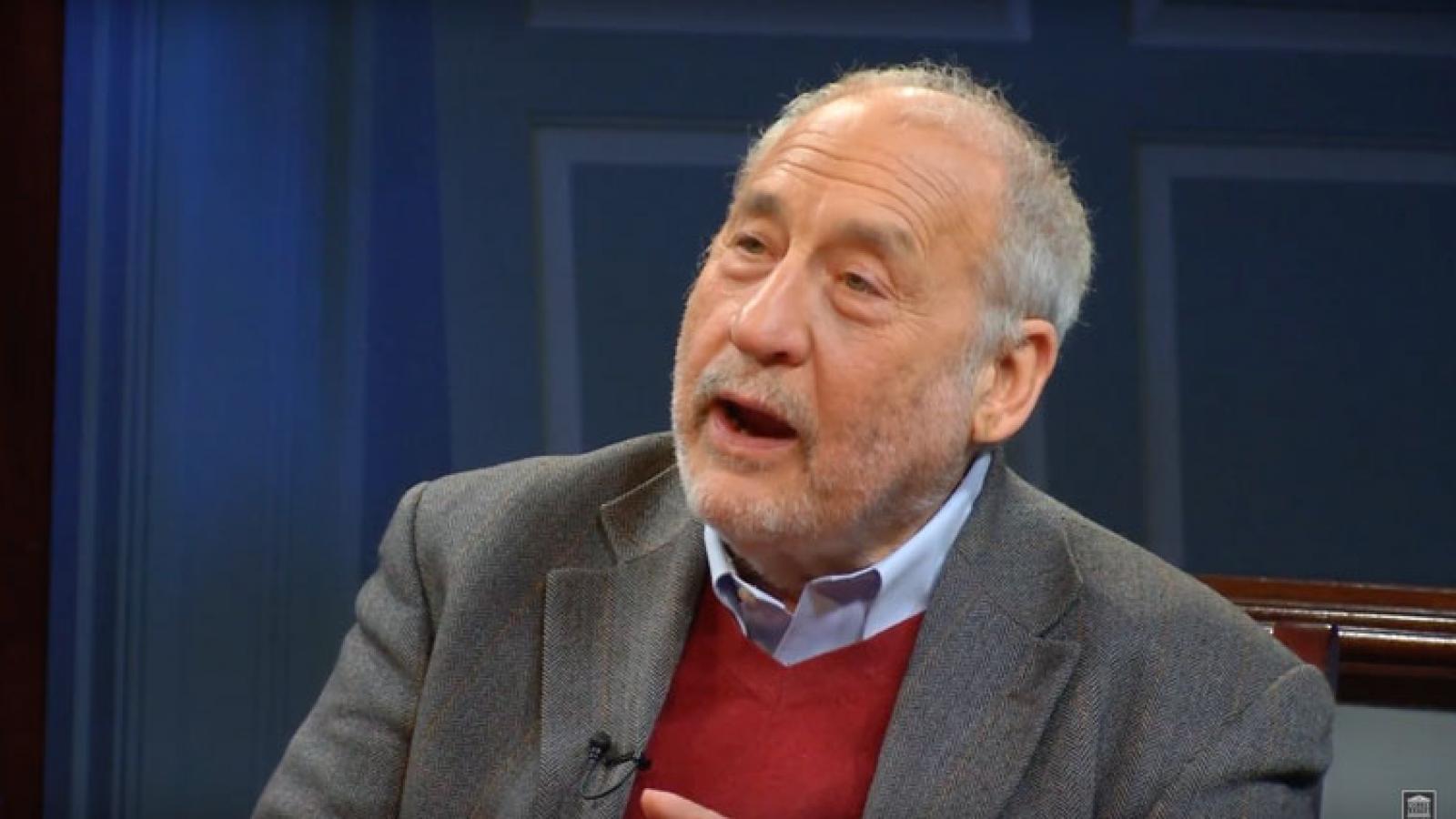

Joseph Stiglitz

Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz discusses income inequality in the era of Trump.

Jobs and Economy

First Year 2017: Income inequality in the era of President Trump

Transcript

Douglas Blackmon in studio: Welcome to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. This week, Nobel prize-winner Joseph Stiglitz talks about the impact of the Trump presidency on our economy.

MAIN TITLES/MX

0:52 Douglas Blackmon: For more than fifty years, our guest this week has been working on the intersection between economics and public policy. Joseph Stiglitz was chairman of the Council on economic Advisors in the Clinton administration. He became vice president and chief economist at the World Bank in 1997. He left three years later, after criticizing some of the bank’s approaches to aid for impoverished countries, and international monetary fund programs in the former Soviet Bloc and Asia. He won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001. He was a member of the United Nations Panel on Climate Change won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, an award it shared with former U.S. vice president, Al Gore. Stiglitz advised President Obama but took issue with the administration’s rescue of the financial industry after the economic collapse in 2008. He is considered by many to be a “New Keynesian” economist. We’re going to find out what that means in today’s political environment and how it all fits, if it does, into this new presidency of Donald Trump. Thank you for being here.

1:53 Joseph Stiglitz: Nice to be here.

1:55 Blackmon: You were writing about income inequality in the U.S. long before it became a kind of marquee issue in our politics and at a time when really, ah, when versions of that issue were talked about, it was thought of more as the sort of entrenched poverty of a mostly African American underclass. That was sort of the stereotypical, ah, picture of what income inequality meant. Certainly, you were writing about it before anyone could have imagined that the stresses of that might trigger the election of an extraordinarily unorthodox president, if perhaps that’s what’s happened. But—so you were way ahead of the curve in these big economic observations. Were you surprised by the events of the past year or did it feel like something that you could have seen coming?

2:44 Stiglitz: It was a train wreck, to use that frame, that you could see coming. I published a book, ah, in 2012 and I wrote an article in a venue that was more popular than my original work, which was in Econometrica. This was in Vanity Fair where I had an article called, Of the One Percent, for the One Percent, and by the One Percent, and both in my book, The Price of Inequality, and in that article, I basically said, look at—inequality is growing to such an extreme that it will have political consequences. It’s dividing our society and when you have a society as divided as we were becoming, inevitably there would be consequences.

FACTOID: Stiglitz argued in 2011 article that rising tide was lifting only the rich

3:31 Blackmon: How was it, when was it, what were the indicators that first began to leap out at that something as severe as what you were then writing about in 2012 was beginning to happen?

Stiglitz: Well, I grew up in Gary, Indiana, which was, ah, a kind of industrial town. It was founded in 1906. It grew with the, ah— [Blackmon: Named after Judge Gary, the one-time CEO of U.S. Steel.] steel, that’s right. So, it was really a company town. You couldn’t have more of a company town than that, and, ah, so I grew up in the ’50s, which was, I then now realize, the peak of this period. But, of course, we didn’t know that. We were in the midst of it and I saw enormous inequality, enormous racial discrimination, as you mentioned, episodic unemployment, and bad labor relations, and that’s what motivated me to go into economics, and I wrote my PhD thesis on the subject of inequality.

FACTOID: National unemployment rate in 1950s ranged from 3% to 6.8%

What I saw happen in the decades after that was that things got much worse. So, very unexpectedly, ah, between, say, 1980 and 2010, the share of the top one percent had doubled. The share of the top one-tenth of a percent had increased three- to four-fold. Back when I was chief economist at the World Bank, I had seen what happened in Russia.

FACTOID: World Bank Finances capital projects aimed at reducing poverty

We had income data that showed that income had fallen by one-third after the fall of the Iron Curtain. That was dramatic. But, we weren’t sure that our numbers were right. But, then we started seeing life expectancy data and life expectancy data was going down by two years among males and mainly for social disease, alcoholism, and then, about a year-and-a-half ago, we started seeing data for the United States that was very similar, that life expectancy of males was going down and it was because of suicide, ah, drug overdose.

FACTOID: Alcohol kills up to 750K Russians yearly; most booze made illegally

FACTOID: Death rate went up by 1.2% in 2015; first rise since 1999

[Blackmon: Opioids.] Opioids, alcoholism, just like in Russia, and the most recent data that just came out in a study, ah, this month shows that these trends have been longstanding, going back to the beginning of the decade, focusing, say, on white males, a group that used to have a higher health and much higher health than, say, African American males, you see a difference whereas in every other country life expectancy is increasing.

FACTOID: See death rate studies by Angus Deaton and Anne Case of Princeton

People are doing better. In the United States, it’s plummeted and is much worse than in virtually any other country of the bank’s countries. So, that should be like a thermometer, you know, that something is deeply, deeply wrong with, ah, what has been happening in America.

FACTOID: Brookings.edu search “mortality and morbidity”

Blackmon: The idea that the U.S. is on a path towards the same kind of desolate, ah, picture of a society that Russia became and that it is the people that in our society we’ve always just assumed to be the permanent highest performers, I mean, that’s really a gigantic change.

FACTOID: Over 30% of deaths in Russia in 2012 were attributable to alcohol

Stiglitz: Yes, it is and, obviously, very, very troublesome. The fundamental problem is that we’ve put enormous strains. We’ve gone from a transformation from a manufacturing economy to a service sector economy. We’ve globalized and, ah, we’ve gone towards a knowledge economy and markets don’t do that well on their own. People don’t necessarily do that well on their own and so the people who have less education, ah less wealth are not going to be able to make the investments necessary to make that transformation. So, they are really being left behind.

7:48 Blackmon: Is part of what’s happened here, ah, a result of a kind of basal anti-intellectualism in American life, that on the one hand, we get the idea and it fits with the American myth, really, our view of ourselves historically that we’re this place where anybody can become anything and anybody can come—become rich and getting rich is a good thing to do, and it is a good thing? Um, it’s a great thing, particularly if you’re the one getting rich. Um, ah, but this idea that that’s all good, ah, and don’t complicate it with a bunch of numbers and complicated ideas of that, well, it’s one thing if we’re going to globalize, we have to take into account that there are a whole lot of other factors here that need to be dealt with and they’re going to cost a lot of money. I mean, is it just a kind of unwillingness of our society to grapple with that this isn’t simple?

Stiglitz: That’s right. The world is complex and, ah, is not going to, ah, be solved by any single or any simple solution. We’ve had tremendous increases in our standard of living over the last two hundred-and fifty years. If you look historically, ah, standards of living were really stagnant for hundreds and hundreds of years before the middle of the eighteenth century and then they started to soar, and if you think about it, what was it that led to that?

FACTOID: Standard of living for average U.S. family doubled from 1946 to 1978

It wasn’t just hard work. It wasn’t even just savings. It was the Enlightenment. It was the scientific method, the fact that we began to think about how we learn, what was knowledge, and then we had these enormous advances in science and technology as a result of this Enlightenment that had brought all the fruits, you know, all the innovations that we now take for granted. Ah, they didn’t happen by themselves, and they’re not simple. They’re really, really complex. So, going back to—we were talking about the—what’s happening to the life expectancy and the stresses, for those who don’t graduate from college, ah, that’s the group that has been most affected, and the United States was the leader in education for a very long time. We’re no longer the leader.

FACTOID: U.S. ranks behind Japan, Russia, Israel, and Canada in education

Ah, other countries figured it out, you know, figured out this idea that you just have to—the world is more complex, you need more education, and so they, as a norm, said you have to go to twelve years, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years of college—of schooling, and we haven’t done that. We haven’t done it.

10:28 Blackmon: Yeah, we lost our, ah, lost our bead on that, I think, in part, because it seemed that, ah, we could have what appeared to be such tremendous economic growth and economic success in the stock market and we democratized the stock market and so you had this much larger population of people that actually began to be paying attention to Wall Street. It didn’t seem like this crazy, speculative, ah, crap shoot that the people had perceived it as in an earlier generation. But, that seemed to also focus people on the idea that that’s the indicator of whether we’re succeeding or not and they lost track of whether wages and things actually were keeping up with any of that success.

Stiglitz: Yeah, exactly. I mean, first of all, I would say it was a fake democratization. So, although they had some share, the share of the shares they had was miniscule and, in fact, the vast majority of the wealth of the country and particularly the stock market wealth was held by the people at the very top, and what was happening to wages was really dismal. I mean, the data today—you look at—you asked me what were some of the indicators that I look at. At the bottom, the real wages adjusted for inflation are at the same level roughly that they were sixty years ago. Median income of a full-time male worker, median, half above, half below, adjusted for inflation and that’s full-time, that assuming he can get a full-time job, is the same as it was forty-two years ago. So, when you think about this, our economy has been growing but not for most Americans.

12:11 Blackmon: So, that gets us into the present, then. I think that’s what’s so fascinating about—about this current situation in our current politics is that we had for a long time this—the left-behind group tended to be racial minorities, in particular, African Americans, and now suddenly we begin to see the outcomes of what you’ve been talking about in more modern times, ah, and a huge population of people who don’t necessarily look like that now feels very left behind, in particular, white males who had—had a reasonable expectation that the world was going to at least work as well to their benefit as it did for their fathers and grandfathers and suddenly it doesn’t, ah, and—and we get into this political environment in which they very much so want someone who will say, no, I can fix all that, and I think that takes us to Donald Trump. Ah, and so in some respects, you see as problems in the society and the anxieties they create are similar to the ones that Donald Trump sees; you know, that globalization, maybe, has harmed these people and that something needs to be done about this. So—but, so what do you think about the way that Donald Trump appears to be saying he’s going to approach these anxieties?

Stiglitz: Yeah, ah, well, there couldn’t be more difference in that. He sees, for instance, ah, he said, ah, we negotiated—our negotiators were terrible. You know, I’ve watched these negotiations very carefully. I’ve known negotiators. They got—the American negotiators got almost everything they wanted; you know, not a surprise. Who’s the big guy in the street? It’s the United States. So, we got what we wanted. We wanted the wrong things and what was it? What we wanted was what was in the corporate interest. So, it was what the billionaires, what the one percent wanted and, you know, they were negotiating for, ah, making it more difficult, for instance, to get access to generic medicines, driving up healthcare costs. So, we were negotiating, you might say, against our interests but for the interests of the drug companies, ah, and the irony of all this is that the drug companies weren’t paying any taxes because they were very—you know, they use globalization to move their money to low tax-based jurisdictions. Well that leads to the question of, ah, is it globalization that’s the problem or how we’ve responded to globalization. So, the description of what has happened is absolutely right. They have been losers. But, the answer is not to walk away from globalization because, look at—we’ve created these global supply chains and to rip those up is going to lower our standard of living, and the people who are going to be hurt are the same people who were hurt before. So, what we really have to do is now to say, OK, you know, we should have done it differently but here’s where we are today. You always have to start with where you are and we need assistance to help those who have been hurt by globalization. We have to have more progressive taxation. We have to tax corporations more, not less, and that will give us the revenues so that everybody will be better off.

FACTOID: Trump wants corporate federal tax rate dropped to 15-20% from 35%

15:29 Blackmon: And what about the—the—in terms of the relatively simplistic—I mean, we really don’t know a lot about, in any sort of detail, what, ah, what President Trump would want to do with NAFTA or, ah, the Trans-Pacific Partnership or those kinds of agreements, um, but—but presumably it’s something, ah, similar to his, um, pressuring companies not to move a particular group of jobs out of the country. Now, he also, ah, seems to be sort of buying those jobs that at a very expensive cost in government funds to try to incentivize companies to stay.

Stiglitz: The basic way of thinking about it is to realize that globally, manufacturing jobs are in decline and most Americans don’t realize that but it’s a simple fact. So, we will have to change. Just like we moved out of agriculture and moved into manufacturing, now we will have to go from manufacturing into services. We can keep some high-tech manufacturing airplanes. I mean, we will have a robust manufacturing sector, but to think that manufacturing jobs are going to—ah, we’re going to bring all those jobs back, go back to the 1950s, that’s fiction. Even if we brought back some of the production, it’s going to be increasingly by robots and, again, it’s not going to—not going to create, ah, the jobs. What he also forgets, that even in those policies like, ah, putting a border with Mexico, ah, if we—if our cars didn’t have to have Mexican parts, our cars would be much more expensive and then they couldn’t compete with the cars from Europe and Japan, and then we have to go and start raising our tariffs. But, that would require—would entail retaliation, and so where he’s going is towards a global trade war, and if we go to that—if we had that global trade war, our standards of living are going to go down. Our jobs are going to go down because we depend very heavily on exports. And I can tell you I just got back from China and, ah, they’re prepared. You know, the premier said, ah, you know, we’ve done studies. There are studies in just oblique reference which show that America will be hurt more than China and they are—they’re ready. So, they have the resources. They’re sitting on ah, ah, $3 trillion of reserves. Ah, they have the tools. They have a—more of a government control, and they’re ready, and so we don’t have the capacity to respond in that way. So, I think it’s extraordinarily dangerous what he’s going towards, which is a global trade war.

18:23 Blackmon: You advocate for things like, ah, greater government investment in infrastructure and sort of these foundational elements of the society. President Trump is talking about having investments in infrastructure. Is he talking about the same thing that you’re talking about?

Stiglitz: Ah, no. Ah, I mean, I guess, the—part of it is—is how you finance it. He’s talked about basically having it financed by very large tax credits, eighty percent tax credits. Hedge funds will do it and, basically, he’s giving away our infrastructure, privatizing it and having them charge.

FACTOIDS: Hedge funds are less regulated, highly specialized investment pools

So, we lose twice. We lose as taxpayers and then we lose—and again because you have to pay for it, and then you start asking the question, what kinds of infrastructure can be paid for in that way, and some of the most important kinds of infrastructure, ah, roads in less dense parts of the country, ah, um, a lot of the infrastructure can’t be paid for by charges, and when you do have charges, it’s the—not necessarily the most efficient way of doing it. So, to me, the, ah—you need infrastructure but let me just give you one example. Ah, one of the kinds of infrastructure that we clearly need is fast trains along the East Coast corridor and the West Coast corridor.

FACTOID: LBJ was first president to back high speed rail as part of Great Society

Um, that is not something that is likely to be on his agenda but would be very good for the environment and, ah, very good for our time.

20:02 Blackmon: Yeah, so, back to your discussion of the trade war, ah, just to throw some numbers out, Canada, Mexico, and China are the trade partners that, ah, most obviously are—would be affected by, ah, obviously, NAFTA—but our imports from Canada down 15.2 percent, 2014 to 2015; down 6.1 percent, 2015 to 2016. So, already, ah, I mean, that’s pre-Trump but the—but the reliance, our reliance on these trade partners who would be in the dead sights of any kind of disruption like one that you were describing before, we’re not talking about—we’re talking about—we’re not talking about marginal, ah, impact on our economy. We’re talking about really the—

Stiglitz: Oh, huge impact. The irony, of course, is that every macro economist recognizes that the overall—what matters for jobs and all that is the multilateral trade deficit. That is basically determined by the difference between domestic savings and domestic investment. When domestic savings goes down, our trade deficit will go up, and his proposals for tax cuts and expenditure increases are going to mean that the trade deficit is going to go up. So, in spite of all that he’s talking and all that noise and all those companies that he’s yelling at and lambasting, in my mind, breaking the basic rule of law because in the basic rule of law, if a country doesn’t like what somebody is doing, you either incentivize them by passing a tax law or you pass a regulation. You don’t pick on particular companies. That’s the way of demagogues and despots.

21:53 Blackmon: Now, we can have somebody at the table here—I’m, ah, I guess, or I’ll try to speak on behalf of the administration somehow but I guess someone could say that, no, you just don’t get it. You know, you’re a real smart guy, obviously, but you just don’t get it. Ah, President Trump does get it, just somewhere in his gut he—you know, he’s going to make a series of decisions that’s going to make all that work somehow, and so I guess I’ll leave open that possibility. But, um, but you have—ah, you’ve said that, ah, I mean, you’ve been pretty harshly critical of—of the, ah, the claims themselves. I mean, you’ve compared, ah, the way, the story he has spun to some pretty terrible things that happened in the 1930s, you know. I mean, but the—what do you mean by that in terms of that the—I think you’ve called all of this “the big lie” or sort of “the big lie approach” to, ah, to trying to make a case to the American people. But, is it that? Is it a big lie or is it that it’s a guy who doesn’t, ah—who just doesn’t understand or is it something even more sinister, in your view?

Stiglitz: Um, you know, we can’t be sure. What we do know is that he does lie. So, we know—you can say you see all the ways that, you know, when you say “lie,” when somebody makes a statement that almost surely unless they’re crazy they know is wrong and persistently does that with sinister intent, you would call that a lie. He continues to say that. I call that a lie.

Blackmon: Well, and you—I was, um, going back to my notes here because I wanted to get to, ah, a specific thing that you wrote at one point relatively recently that we’re—you said the big lie was reminiscent of the approach of— [Stiglitz: Goebbels.] of Goebbels in Nazi Germany, yeah. Now, is— [Stiglitz: And you’re seeing it over and over again and some people are going to believe it.] Yeah, but, so, ah, I mean, I guess some could say that, you know, or that maybe you’re going too far. I mean, that’s a big thing to—to make that comparison ah, to the Nazis or is that a fair comparison?

Stiglitz: I think it’s a fair comparison. I mean, one of the reasons why it’s a fair comparison was that Goebbels was very explicit in the view that—of a theory of knowledge because he believed that if you say a big lie often enough, it will become believed.

FACTOID: Joseph Goebbels was propaganda minister of Nazi Germany, 1933-45

So, he was trying to think about how do people perceive—get perceptions. Now, when you start talking about alternative facts, you are beginning to say, how do we know what we know and you are undermining the basis of our knowledge.

Blackmon: Joseph Stiglitz, I could talk to you for hours but I don’t get to. Thank you for being here.

Stiglitz: Thank you.

Blackmon: Before we wrap up this episode, a special shout out to our friends and collaborators at the Virginia Festival of the Book, where Professor Stiglitz recently made an appearance. We hope you will join us for future editions of American Forum, where our focus is always on the presidency and civil conversations about the most critical issues faced by our nation. In upcoming episodes, we’ll have conservative icon Bill Kristol, Northwestern professor Geraldo Cadava on what the future holds for Hispanics in this country, and historian and author John Farrell on his new much talked about biography arguing that peace talks between the U.S. and Vietnam were sabotaged in 1968 by presidential candidate Richard Nixon. You can watch us on your local PBS affiliate. Or to participate in our ongoing conversation, look for us on the Miller Center Facebook page, visit our new, very cool website at MillerCenter.org, or follow us on Twitter. My handle is @douglasblackmon. Our guest is @JosephEStiglitz, just like it appears on the screen. I’m Doug Blackmon. See you next week.