Reagan vs. Air Traffic Controllers

August 3, 1981: 'Tell them when the strike's over, they don't have any jobs'

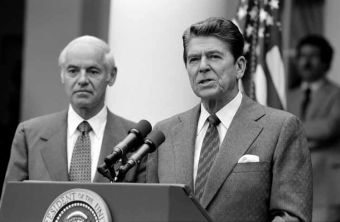

“They are in violation of the law, and if they do not report for work within 48 hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated,” President Ronald Reagan said at a press conference on August 3, 1981, responding to a nationwide air traffic controllers’ strike. Members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO), one of the few unions that endorsed Reagan during the election of 1980, were picketing for better pay and working conditions when about 13,000 of them walked off the job.

Two days later, when most PATCO workers did not return, it became clear that Reagan was not bluffing. On August 5, he fired 11,345 of them, writing in his diary that day, “How do they explain approving of law breaking—to say nothing of violation of an oath taken by each a.c. [air controller] that he or she would not strike.”

Reagan took no joy in doing it, however. The law was the law, and he believed public safety workers had no right to strike. It was the same approach Reagan’s hero Calvin Coolidge took when the Boston police went on strike in 1919.

The firing slowed commercial air travel for some time, but it didn't come to a grinding halt, thanks to the Federal Aviation Administration's work-around: Supervisors, non-striking controllers, and military controllers were able to fill in for the picketers, in short order handling 80 percent of what had been the prior workload. In the meantime, the FAA began the long process of hiring new controllers, taking years to reach pre–August 1981 staffing levels.

The mass firing was a controversial move by Reagan, but one that members of his administration remember as an example of courage, as you can read in these excerpts from the Miller Center's extensive Reagan oral histories.

Howard Baker, Jr.

Senate majority leader; chief of staff

The president, right off the bat, said, “Are they striking legally?” And the answer was, “No.” And he said, “That’s not the way people ought to work. Tell them when the strike’s over, they don’t have any jobs.” It was a very decisive move. It enhanced the power of the presidency significantly at that time. Most of the American people didn’t support the idea of a union that was a public service union and was legally barred from striking. They didn’t want them to strike. They didn’t want to support it. So we had the support of the vast majority of the American people.

Michael Deaver

Deputy chief of staff

I don’t think he thought of it as a seminal moment, but it turned out to be. It was interesting to me, because it goes right to this business about staff, and who’s making the decisions. I remember that morning in the Cabinet meeting—the Cabinet’s all around the table, and everybody had ideas, and Drew Lewis—who was [Secretary of] Transportation—and others were going back and forth across the table. I looked over at Reagan, because it dawned on me that he wasn’t saying anything. He was writing on his yellow pad, writing, writing, writing. This went on for about 15 minutes, and finally I heard him say, "Excuse me, fellows, but let me just read you something here. Tell me what you think about it." It was the statement he gave in the Rose Garden about half an hour later, word for word. Nobody changed anything. Everybody said, "Oh, yes, that’s great."

But it wasn’t a surprise to me, because it had been a Reagan position in California when the firefighters, I think it was, went out. Reagan said, "A public employee does not have the right to strike. How can you strike against the public? They’re the people who hire you." He’d had that experience with teachers, saying, "They insist on the right to strike and tenure at the same time, how can you do this?" So it wasn’t a real surprise to me. I guess what was the surprise was that in this first example of his own action, it was pure Reagan, and it wasn’t changed in any way.

Edwin Harper

Assistant to the president for policy development; deputy director of OMB

Well, one of the things that really impressed me was his courage. For example, the air traffic controllers strike: Calling their bluff on that was a real act of political courage. It took on a group that nobody had ever been willing to confront before. He did it with his eyes wide open and went ahead. It was Drew Lewis’ call in some ways, but Drew Lewis was not going to do this without Ronald Reagan’s permission—and I think that was a real act of political courage to do that. And it set the tone for a lot of other things.

Paul Laxalt

Republican Senator from Nevada

I was so proud of him. We all were when he stood firm. It wasn’t really surprising. They defied authority, and he wasn’t about to let them get by with it, not on his watch.

Q: Was there early warning of that strike? Was this something that he was anticipating?

Laxalt: I think that Drew Lewis was working in it principally, and I think he came back with a reading that they could well strike and force his hand.

Q: So it didn’t take the president entirely by surprise.

Laxalt: No, not entirely. He wasn’t going to tolerate that. And I agree with you, I think that established him in the minds of an awful lot of people who aren’t that political as a guy who is going to stand up and be counted. Despite all the gloomy predictions that we had—the whole system would break down, we’d have crashes everywhere—all those spots where they portrayed Reagan as an evil person.

Q: Did your colleagues in the Senate react in any discernible way that you recall? Did that impress them?

Laxalt: Well, it would all depend, obviously, on their politics. A lot of our Democratic colleagues with strong union leanings didn’t like it a bit because that didn’t send out a very decent message as far as the union supporters were concerned. Conservatives loved it, of course, and the moderates, depending, I guess, on their constituencies. But he just developed a hell of a lot of respect for standing up and being counted, in Harry Truman style. You know what I mean? Right now, I think from that point on, the power centers in this town figured, here’s a guy you better take seriously.

Martin Anderson

Assistant to the president for policy development

I think what is extraordinary about that is the impact that it had way beyond domestic politics. Especially when you listen to George Shultz or Henry Kissinger talk about the impact it had on foreign policy, it was stunning. Basically, the impact was that they said, “Oh my God, this president took on the unions and did it? He might do other things.” Which was true, of course.

What he did with PATCO—at the time it was presented, they were going to strike. When he was told about it, he just said, “No, they can’t strike.” It looked like off the top of his head he had done that. Well, when we were putting together this book Reagan, In His Own Hand, my wife and I found some of these essays that he had written dealing with strikes by public employees. Many years ago he had very carefully laid out, analyzed it, studied it, and said, “Look, they cannot strike. And if they strike, they’re gone.”

So what we did not realize while we were in the White House with him was that he had already thought about this. He had worked out the theory, he had a whole thing all set up. Then they came and said they’re striking and he said, “Fine, they’re gone.”