In the beginning: Medicare and Medicaid

The law LBJ signed on July 30, 1965 directly affects more than 100 million Americans

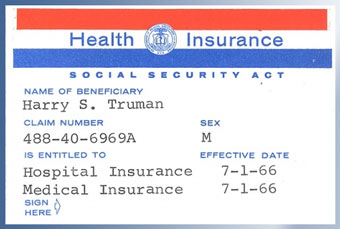

The first enrollee in Medicare might have been the most famous. On July 30, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson boarded Air Force One for a flight to Independence, Missouri, where he would sign the Social Security Amendments of 1965 into law at the Truman Presidential Library—with former President Truman at his side. The act established Medicare to provide health insurance to the elderly and Medicaid to provide the same to the poor and disabled—and taxes to pay for both. After attaching his signature to the legislation, Johnson presented the first two Social Security Administration health insurance cards to Truman and his wife, Bess.

Today, Medicare and Medicaid are immensely significant in human, economic, and political terms. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which administer the programs, roughly 57 million Americans are enrolled in Medicare and 70.9 million in Medicaid, with nearly 12 million in both. Medicare and Medicaid account for more than a third of the $3.2 trillion health care industry that represents 17.8 percent of the US economy (a far greater share than the 9 to 12 percent typical of other Western economies). And Americans continue to vigorously debate the role of the federal government in providing the physical and economic security afforded by health insurance.

From failure comes success

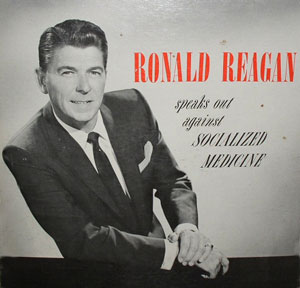

Johnson wasn't the first president to attempt to carve out a role for the federal government in health care. During the crafting of the 1935 Social Security Act, President Franklin Roosevelt dropped the health care provisions in order to ensure passage of the bill. Truman, as Johnson well recognized, was the first president to publicly push for a national health care system, one that would accommodate all Americans in need, but he ran into the staunch opposition of congressional conservatives and the American Medical Association (AMA), which labeled the idea "socialized medicine" and part of the "Moscow party line." During the 1950s, as increasing numbers of Americans acquired insurance through work, members of Congress focused on coverage for the growing elderly population to revive the idea of a federal health system, counting on the popularity of Social Security to help ensure the idea's success. President John F. Kennedy embraced the idea, telling a nationwide audience in May 1962, “The fact of the matter is that what we are now talking about doing, most of the countries of Europe did years ago. The British did it 30 years ago. We are behind every country, pretty nearly, in Europe, in this matter of medical care for our citizens.”

After Kennedy's death, Johnson pushed for the passage of Medicare before the 1964 election. In particular, he sought to convert influential House Ways and Means Committee chairman Wilbur Mills, a Democrat. Mills was concerned that, because current proposals covered only hospital and nursing home costs, seniors might be disappointed when they discovered that Medicare did not cover doctors’ bills—and then blame the Democratic Party.

In a June 1964 phone call, Johnson and Mills discuss the political implications of the bill. Mills begins this excerpt by discussing attempts to report the bill out of committee:

After Johnson's landslide victory, passage of national health insurance for the elderly appeared imminent. The idea was popular, Democrats held solid majorities in both houses of Congress, and moderate Republicans were seeking to move toward the political center in the wake of LBJ's massive triumph over Barry Goldwater. Still, the particular form of the program, how much it would cost, and how it would be payed for were very much up for debate—and there were several proposals circulating around Capitol Hill.

As Mills had anticipated, Republicans criticized the lack of coverage for physicians' fees and prescriptions, and offered plans to add those benefits. Other members, including Mills himself, were concerned that the rising costs of health care would leave the Social Security trust fund vulnerable. Thus in its final form, the bill included coverage of physicians' fees and provided for a separate trust fund for Medicare. And to decrease the opposition of the AMA, the final bill left physicians and insurance companies with a substantial amount of control over fees. In the following March 1965 phone call, recorded on the day the bill was finally reported out of committee, Wilbur Cohen, the assistant secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, explains these provisions to Johnson as Speaker of the House John McCormack, House Majority Leader Carl Albert, and Mills listen in.

After House and Senate versions of the bill were reconciled, the final version passed the House on July 27 and the Senate on July 28, before Johnson signed it into law. But the story of Medicare and Medicaid—and the role of the federal government in health care—was far from settled.