About this episode

October 15, 2017

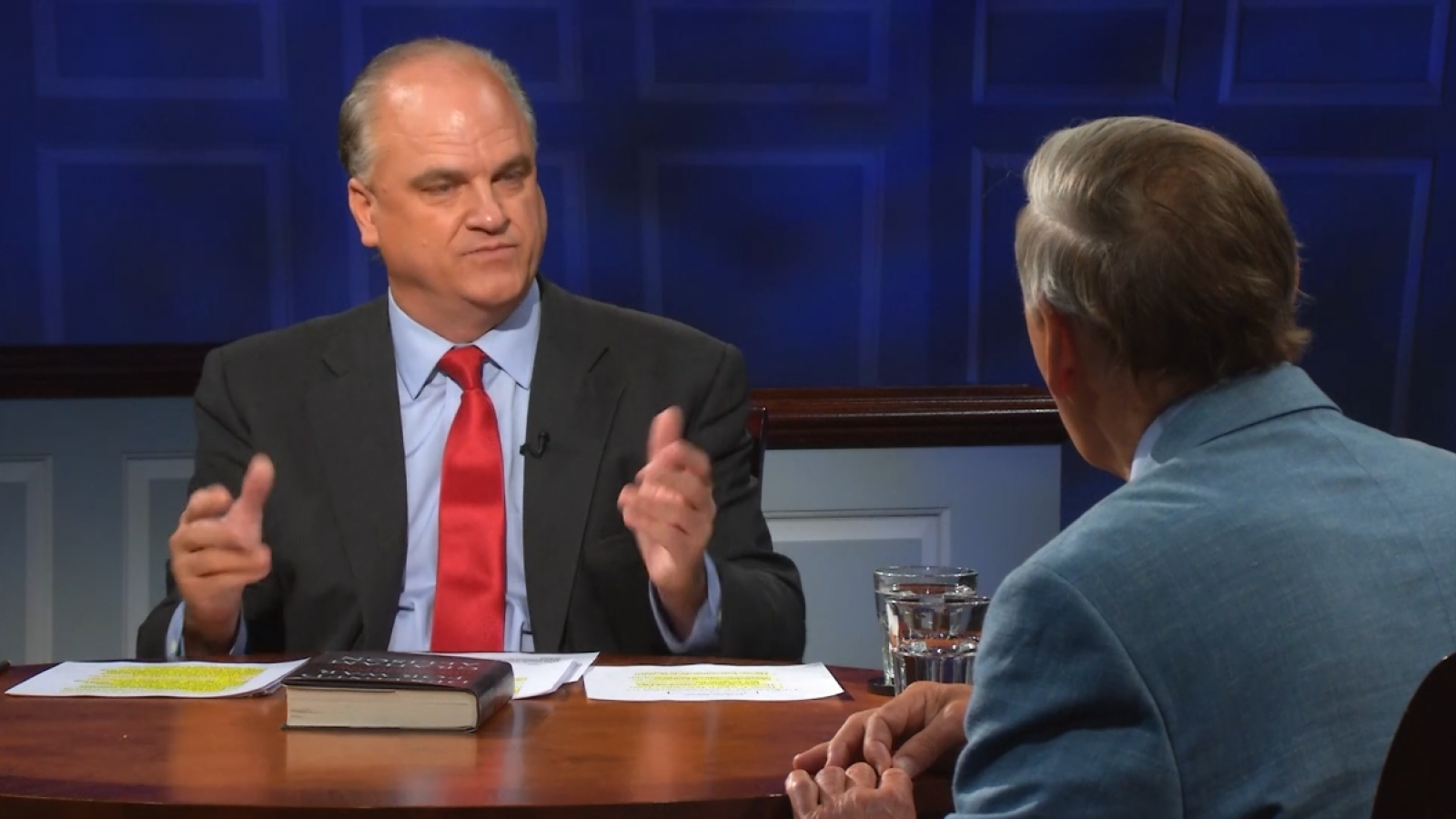

Graham Allison

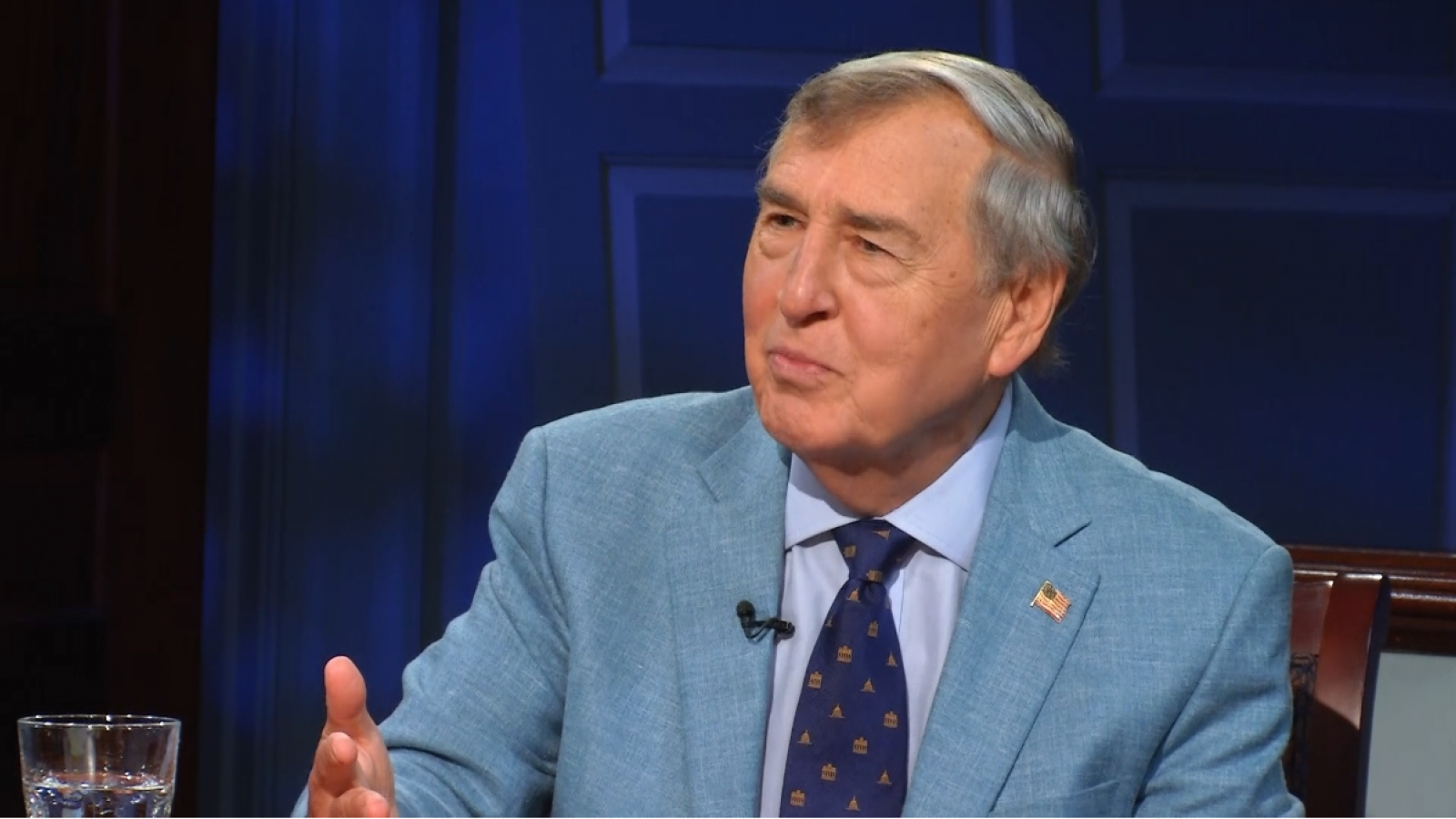

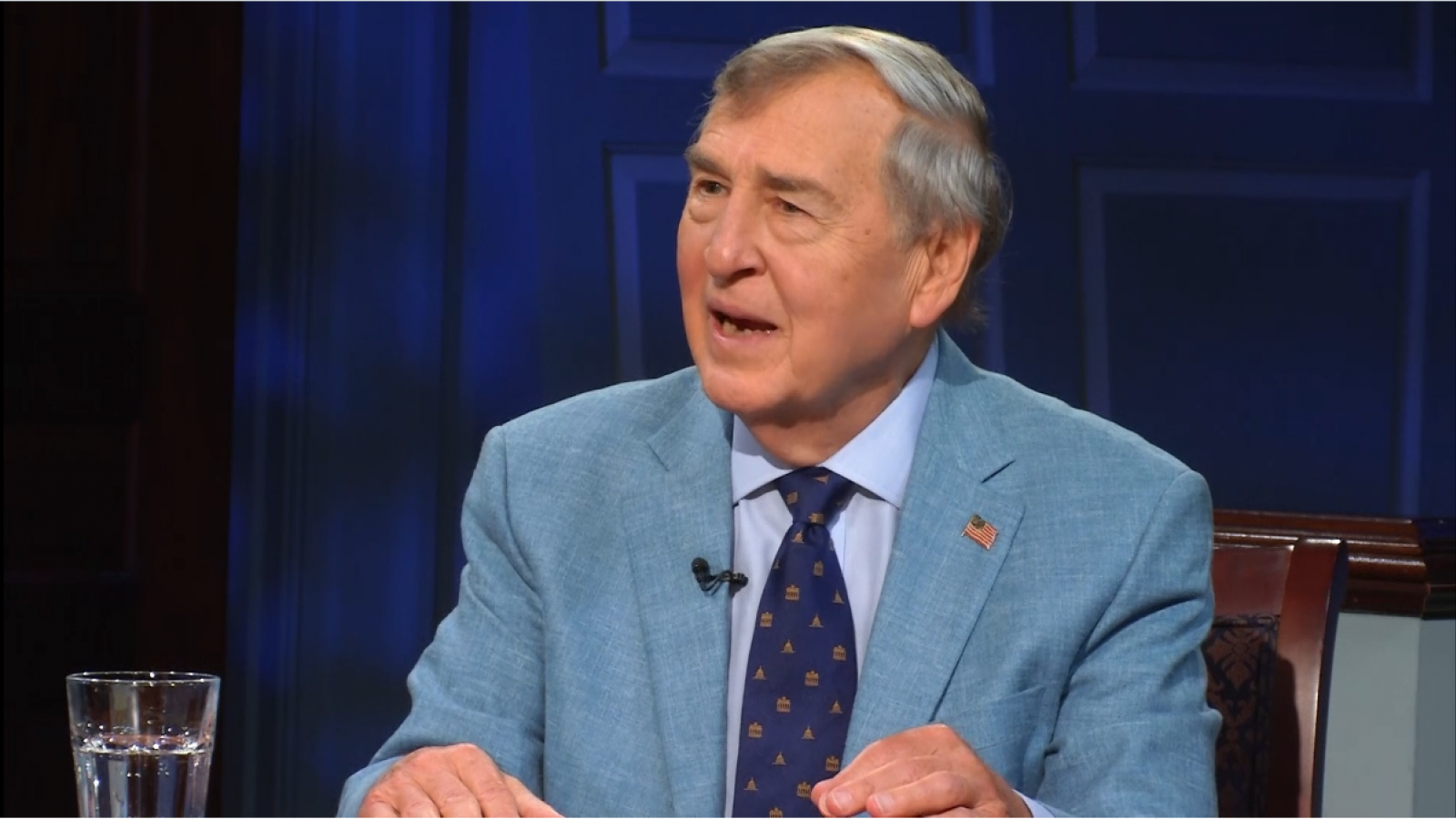

Hosted by Douglas Blackmon

The relationship between the US and China is at its most uncertain since Richard Nixon restarted the dialogue in 1972. While some argue that China is a vital trade partner in a growing global economy, others prophesy a bubbling conflict that could escalate to war. With the North Korea crisis potentially coming to a head, can Xi Jinping and Donald Trump find common ground? Our guest GRAHAM ALLISON, dean of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, has written a provocative new book exploring this remarkable shift in global supremacy.

Foreign Affairs

Are the US and China Destined for War?

Transcript

00:41 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. A quarter century ago, the United States was the world’s unchallenged military and economic superpower. It’s primary foe of the previous 50 years, the Soviet Union, was a dismembered wreck. China remained mostly a third-world backwater. The U.S. military had just stunned China and Russia with a blitzkrieg that instantly obliterated the once-formidable army of Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein. U.S. financial markets were surging, and the first signs were appearing of an American technological revolution called the digital economy. Red-white-and-blue democracy had decisively prevailed. Yet, just three decades later, the global landscape is vastly different. Years of continuous warfare has demonstrated the limits of American power. Economic growth has been stagnant for a generation. Millions of Americans doubt the effectiveness and fairness of our own economic system. A ferocious Russian bear zombie has risen from the grave of the Soviet Union. And China is a new global juggernaut—its total national economic output has exploded from less than $40 billion in 1980 to more than $11 trillion today. Our guest in this episode is Graham Allison, who has written a provocative new book exploring this remarkable shift in global supremacy. It is titled Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? He is director of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, and one of the most influential voices of his generation on decision-making in times of international crisis. He argues that the stunning rise of China presents a grave challenge to America—and that the history of rising new powers and the societies they eclipsed is a warning that the U.S. and China could soon find themselves destined for a potentially catastrophic conflict. Thank you for being here.

Graham Allison: Thank you for having me.

2:40 Blackmon: So let’s first just figure out exactly what is Thucydides’s trap. The historical reference is to war between Athens and Sparta a millennium ago and the idea that this was triggered by the rise of Athens and the anxiety that that created for Sparta. But work through exactly how you take from that to this larger argument that relates to the time we live in.

Allison: So I think you captured it well. Thucydides’s trap is the dangerous dynamic that occurs when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power. Thucydides wrote about the rise of Athens and its impact on Sparta, but you can think about the rise of Germany a little over a hundred years ago and its impact on Britain, which had ruled the world for a hundred years, or the rise of China and its impact on the U.S. just as we’re coming out of what we regard as the American century.

FACTOID: Thucydides was Athenian general and historian in 5th century BCE

Thucydides taught us that when a rising power is rising it says, “I’m bigger. I’m stronger. I deserve more say. I deserve more sway. Current arrangements were put in place before I even mattered, so they’re unfair.” And the ruling power says, “The status quo is not just the status quo. It’s the order. It’s a good order. It’s the only order in which you were able to grow up. You should be appreciative. You should even share some of the burden. You should be a responsible stakeholder.” So in those circumstances, misunderstanding is rampant, and both parties are vulnerable to third-party actions, which they don’t control and which they didn’t anticipate, which would otherwise be inconsequential or easily managed, that drag them somewhere they don’t want to go. World War I is the classic example. How in the world could the assassination of an archduke in Sarajevo by a Serbian terrorist create a fire that burns down all the houses of Europe?

FACTOID: Austria’s Franz Ferdinand killed by Gavrilo Princip June 28, 1914

I mean, I have a good chapter on that in the book. I’ve been studying this thing for 50 years. I still don’t know the answer.

4:40 Blackmon: But you looked at, in the end, 16 case studies over 500 years, and I think you concluded that 12 of the 16 of these sorts of situations you identified ended up ultimately in war between these two powers.

Allison: Exactly, so I’ve looked at the last 500 years. I’ve found 16 cases. This is part of an ongoing, open case file at Harvard, the Thucydides’s Trap Case File, because I’m not sure these were all the cases. I would love to have more cases. This is not a statistical study. This is trying to understand the phenomenon. But in 12 of the 16 that I found, the outcome was war. Four, it was not war, so the Thucydidean line that’s often quoted, “It was the rise of Athens, the fear it instilled in Sparta, that made war inevitable,” that was an exaggeration. He just means “likely,” “very likely,” but I’d say on the record more likely than not. And therefore, to understand that this is the dynamic in the grips of which the U.S. and China find themselves will help us appreciate the dangers that we face and the ways in which even something as crazy as Kim Jong-un in North Korea could, by his own actions, drag the U.S. into a China—the U.S. and China into a war that nobody in China wants and nobody in the U.S. wants, but nobody in Europe wanted the war they got.

FACTOID: North Korea conducted 15 missile tests February to September 2017

5:55 Blackmon: Whenever we use words like “destined” or “destiny” or “a sense of fatalism” or “inevitability,” those are things that are, on the one hand—uh, they can be unpersuasive, this idea that there are these sort of massive forces in the universe somehow as opposed to individual human decisions, but these case studies that you’re looking at speak to a kind of balancing act between these forces that are set in motion and where they’re likely to go but that then are not necessarily destiny, that can be turned or controlled by the individuals who are engaged.

Allison: Exactly right, and, in fact, “destiny” is kind of a complicated word. And I say in the book—and Thucydides basically believes—destiny can—deals the hands, but individuals then play the cards. So I say I’ve met many, many people who were destined for greatness who didn’t quite make it, and I’ve met a huge number of people as a professor over many, many years whom nobody would have imagined would change the world, and they did. So, basically, the hand you inherit is where you start, and it would be foolish to deny that framework. On the other hand, the ways in which individuals make their choices is what was fascinating to Thucydides. He came on the scene in classical Greece when the playwrights were having the gods controlling everything, so Oedipus didn’t have any choice about his behavior.

FACTOID: Oedipus was prophecized to kill his father and marry his mother

He was fixed, but Thucydides said, “No, no, no. Human beings are making choices. Even though difficult circumstances—can we learn from the mistakes they made as well as from their successes?” That was the purpose for which he wrote his book, and it’s actually the first ever history book. I mean, he’s the father of history, so I think for one of the hopes of the—that I have in the book is that people will remember Thucydides should be part of every educated person’s mental library. They should go back and read even just Book One, the first 100 pages of the history of the Peloponnesian War. If every other page it doesn’t knock your socks off, I would say, “Check your pulse.” (laughter)

FACTOID: 404 BCE: Peloponnesian War ends, Athens surrenders to Sparta

8:05 Blackmon: Good advice. Well, let’s—let’s apply this lens that you’ve created. Now, let’s apply it to the China–U.S. situation. Since 1980 or in 1980, China’s trade with the outside world was less than $40 billion. By 2015, it’s $4 trillion. China’s GDP in 1980 equaled seven percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. In 2015, now, it’s 61 percent, a massive, exponential increase. Exports rose from eight percent to 151 percent, imports from eight percent to 73 percent. China’s growth has been 10 percent a year, doubling every seven years since 1980, and you point out a number of these sorts of measures, but one is that every two years since 2008 China’s growth has been larger than the entire Indian economy, and China creates the equivalent of Greece every 16 weeks and Israel every 25 weeks, so this explosion of economic activity. And all—there are many, many other of these measures in terms of consumption of resources and making cars, buying cars, all of these things. Does that add up to that China has already surpassed the United States as the greatest economic power? Is that over?

Allison: Well, it’s a great question. So never—I think most Americans haven’t really focused on this, but never before has a nation risen so far so far on so many different dimensions. I have a good 20-page version of just trying to capture it, and I quote Václav Havel, the former president of Czech, who says, “Things have happened so fast we haven’t yet had time to be astonished.”

(laughter)

FACTOID: Havel served as the first president of the Czech Republic 1993-2003

I would say if you look at the facts it is astonishing. So from nowhere comes a country that’s now rivaling and even surpassing the U.S. in many, many different domains. And, in fact, even the size of the national economy that you referred to, that’s measured by market exchange rates. If you take the—what both the IMF and the CIA agree is the single best yardstick for measuring sizes of national economies, China’s economy today is bigger than the U.S. economy, bigger than the U.S. economy. The big takeaway from the 2014 IMF–World Bank meeting—you can go Google it and see—was, “China is now the number-one economy in the world. China is the number-one growth market in the world.

10:27 Blackmon: And so, in terms of the U.S. and China, the—this question of whether Chinese values and—though, I mean, just saying that as if that is a definable, uh, coherent thing is overstating it, but that—the notion that Chinese values and American values, whether they can cohabitate as rivals or peers in this world. Uh, and you—you talk through some of the risks of that.

Allison: Well, the—I have a chapter on the clash of civilizations, in effect, starting from the big idea of my former colleague, Sam Huntington. And I think, actually, there is a clash of civilizations and core values between the U.S. and China. If you look at what the U.S. stands for in terms of the concept of individual liberty, individualism, rights, democracy, order on that basis, on the one hand, and what the Chinese core values, in which community is way more important than individualism—indeed, as one of my close Chinese friends says—he says, you know, “Your concept of individualism we call selfishness.” OK? Order is way more important than chaos. They’re terrified of chaos all the time. That order then is created by hierarchy in which you have the top of the pyramid and the middle of the pyramid and the bottom of the pyramid. And in an appropriate pyramid, China is at the top of the pyramid the way, in their cosmology, it was for 5,000 years, and other states are tributaries to that. So kowtowing, what is that about? That’s about me showing that I understand that you’re the person that’s superior to me, and I adapt and adjust to you. So whether these competing conceptions of how we ought to order our lives can cohabit I think will be one of the big, big, big challenges.

12:19 Blackmon: The way we’ve been talking about China and the way the first part of your book maps out this juggernaut, it would seem to suggest that perhaps democratic capitalism, the political and economic system that—on which the United States and its allies came to supremacy and which we have always, uh, been encouraged to believe is in fact the best system and ultimately would prevail on the basis of its own power, the power, the right—the correctness of it, are we to contemplate that what all this means is that a market controlled economy, a politically controlled market economy, still a totalitarian state, is in fact perhaps a better system of economics and governance?

Allison: Well, that’s the $64 million question. So at the conclusion of the book, I raise a question like this in which I say, “If you look at it over the long run, there are two big questions that both Xi Jinping and his successor and Donald Trump and his successor should think about.”

FACTOID: Xi Jinping elected president of People’s Republic of china in 2012

The first question is can their current system of governance govern itself inside its own borders, because I think if Americans were to look at what our problems are, our first, second, and third questions, all are at home. And I think if the Chinese were to look at their questions, their biggest questions are all at home. Xi Jinping has undertaken the most remarkable set of reforms ever, ever. I mean, this is almost like Mao’s Cultural Revolution, but he’s doing four reforms simultaneously, trying to transform China and any one of which is just, you know, like, over the top. So he’s trying to rehabilitate a Communist Party in which there’s no Communists. So you could find more Communists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, than in China. (laughter) There’s no single person in China who has any affiliation with these thoughts. “Well, now, how about we just call it ‘the Party?’” “OK, that’s fine. Well, what does the Party believe in?” “Well, we believe that we should rule you.” “Well, OK, I need a little more than that.” OK, so they’re trying to invent some version of New Mandarins who are more virtuous than other people, and therefore they can manage the government more successfully. They can deliver the goods. People will let them do it. And if they succeed, if that works as it has been working, it’s going, I think, to be for the first time—at least in my lifetime—a serious challenge to our confidence that democratic capitalism is the only right answer, because if we go back to where you started the program, 25 years ago with the end of the Cold War, at that point we all were absolutely confident that democratic capitalism had won the day. I mean, Frank Fukuyama wrote a great book called The End of History, so there’s not going to be any more ideological debates or discussions. We know that everybody is going to have a market economy because that’s going to make them more wealthy. Then, they’re going to have a democracy. That’s going to make them more successful governing themselves, and then they’re going to have peace, as you remember, because as Tom Friedman said in the famous Golden Arches theory, “If two countries have McDonald’s, they can’t fight each other.” OK? Now, when we look back on the—this—I would say this sort of celebratory moment at the end of the Cold War, it looks a little naïve at this stage. I think about the U.S., and I’m sure you’ve dealt with this in your other programs. I think serious Americans rightly are asking questions about whether our current democracy is dysfunctional. I mean, I wrote three, four years ago a peace about how DC has become an acronym for “Dysfunctional Capital.” So this is long before Donald Trump showed up. He’s actually part of the—I think he’s part of a phenomenon that—or part of the expression of a lot of Americans’ notion that—how is Congress working? Terribly. OK? How is the Congressional–Executive relationship working? Terribly. How has the American economy been performing? Terribly relevant—relative to our potential, so I think we have plenty of things to worry about in terms of ourselves internally. Now, I'm probably too sort of ingrained with the notion that democratic capitalism is the right outcome to really rethink those questions, but I think the questions are live, and I think they should lead us to a lot less complacency about the notion that, “Well, things are just going to work out fine if we keep doing what we’re doing.”

16:55 Blackmon: It’s easy to imagine that China is a country that, because it does still have so many people in poverty, so many people in places that have modest education, it still has so many problems fundamentally that it can grow dramatically just by addressing those internal issues for a pretty long time. But that doesn’t necessarily suggest that it’s going to do better at these soft, complex issues of social development that also bedevil more developed societies, right?

FACTOID: State media estimates over 43 million Chinese still live in poverty

Allison: Well, that’s another great question. So, yes, I agree with you that—I think that we don’t want to forget there’s another 500 or 600 million Chinese waiting to behave like the first—

Blackmon: The other—

Allison: —900 million. So if they just do what the others have been doing, they can sustain a reasonable—but, secondly, once they get to the frontiers, as they are, for example, in many technologies, well, they’ve got all the problems of anybody at a technology frontier. You try something, and it works, or you have to try other things. For a long time, Americans have comforted themselves on thinking, “Well, the Chinese can’t really innovate. They can’t really invent anything. They’re just going to copy things we do, and then, of course, they can copy them and make them cheaper, but they’re not going to be at the edge of things.” And that, I think, is eroding for anybody that’s watching. So a good, dramatic example is in supercomputers. One of the most important contests relevant for both intelligence and for design are supercomputers. China was not even in the race in 2010, so the top 200—they run a contest every year—didn’t even make it into the thing. Last year, they won four of the five top places. Whoa, what happened? In education, Chinese universities have just been sprouting like rockets, like juggernauts, as you said. I think the big question, back to where we were before, is can somebody govern this system, because you’ve got so many people. You’ve got so much creative [inaudible]. People get richer or get stronger, ah so they want to have more say about their lives. And now, somebody says, “Well, OK, but I’m from the Party, and we’re only three, four percent of the population, and you shut up. We rule you. If we decide you shouldn’t go to some websites, you shouldn’t go there. If we decide that we want to lock up somebody, we lock them up.” When you look at the Nobel Prize—Peace-Prize-winning dissident who was celebrated in the West for his dissidence, the Chinese put him in jail and would let him rot until he died. So I would say this is a pretty different idea about how to rule people than we have.

19:46 Blackmon: And, ultimately, it seems that the—what you’re saying is that by being wise to these forces and where they might lead and the terrible places they could lead, that, in the end, what—the only real resolution, the only—if there is a silver bullet, the only crisp resolution to all of this is for these great societies to accept the idea that there cannot be one supreme force in the end and that there are things that a power might not like but that they decide to live with rather than have much worse things. And so the idea that, in the end, China and the United States could, in fact, coexist relatively peacefully, recognizing that neither of them is ever going to really be the dominant player. Is that—is there any solution other than that?

Allison: I mean, I would say that there’s no—there’s no ultimate solution. History doesn’t end. It just evolves. And could I imagine the U.S. and China finding a form of accommodation that both could live with for the next 25 years? Actually, in the conclusion of the book I say, “I’m not—I don’t know what to do, but I—why don’t we just stretch our minds, because that’s what we need to do?” So suppose Pericles were to come back, and he would say, “I’ve got an idea.

FACTOID: Pericles (495-429 BCE) was an Athenian general and statesman

We had the 30-year peace. We negotiated peace between Athens and Sparta where for 30 years you worry about your problems. I worry about my problems. We’re not going to [inaudible] the problems between us.” Would that be a good deal now? Absolutely. Now, 25 years from now, will China have discovered that it can run a retro-authoritarian system in a world with smart phones? I don’t think so. I mean, they’re going to have to—how is that going to work? And 25 years from now, will we have found a way to make our democracy less dysfunctional? I hope so, but if we haven’t—so if we don’t, well, then I can—because ultimately the correlation of forces changes over time. So how are they going to change? Yes, on the one hand, if they’ve got four times as many people as we have, if they don’t screw up badly, they may have a bigger economy than we do while, on the other hand, we have a bunch of allies and friends that have been good allies and friends for a long time. So we don’t have to have only on our side of the seesaw just us. Maybe you have Europeans. Maybe you have Japanese. Maybe we have South Koreans, and does—does what China want in wanting to be great and to be respected—do they have an imperialistic idea that they want to be in control of us or they want to change our government? This is not the Communists that we saw in the Soviet Union. They’re not out on a revolutionary thing. They just want to be bigger and stronger in their own space. Now, of course, since we’ve been the big, strong guy in their space, that is going to be pushy. That requires some adjustment, and I think the adjustment will ultimately reflect the underlying correlation of forces. And the underlying correlation of forces is not given by any destiny. It has something to do with whether we make right choices or wrong choices.

22:55 Blackmon: Uh, in terms of North Korea, and you mentioned, uh, the Cuban Missile Crisis that faced President Kennedy as well, that’s another thing, another, uh, off—frequent commentary on your book has been that most of these scenarios we look at from history predate the development of nuclear weapons. But so does that, in essence—the mutually assured destruction argument, uh, does that mean that maybe what happened between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs is really not all that relevant to the present?

Allison: Well, I would say, uh, yes and no. OK? Sorry to be professorial, but there’s no question whatever that nuclear weapons—once they get to the level that you and I both have so many weapons that after I’ve done my best to disarm you, you can still destroy me—have a huge crystal ball effect. So anybody who wanders into a president and says, “I’ve got a good idea. Why don’t we attack the other guy?” Somebody says to him, “Mind you, we’re committing suicide,”—the appreciation that we survive in a very, very dangerous environment—and I don’t think there’s any grounds for comfort or confidence or certainly not complacency about the notion that, “Well, since the Chinese have nuclear weapons and we now have nuclear weapons, we could never find ourselves in a war,” in the same way that I think the—another thing that’s a very positive feature in the current, uh, relationship, we have such thick economic entanglement that if we had a war between the U.S. and China, you know, we would go to Walmarts, and they would be empty. OK? There’s nothing to shop for, and the Chinese factories would be making stuff, and they don’t have any place to send it. And besides, we couldn’t get a loan. The best-selling book in Europe in the decade before World War I was called The Grand Illusion. The Grand Illusion said that you could benefit by war, so it said, “There’s not going to be more wars because anybody can see we’re so economically entangled that, at the end of the war, you will have lost more than you could possibly gain.” Well, that turned out not to be right. So I would say we shouldn’t—shouldn’t be—we should try to take advantage of the areas in which we have a shared, an essential, an inextricable shared interest with China, so that’s why wise people would be building on that and, in that framework, dealing with the areas where we have significant differences, make it more adjustable than thinking we have this huge conflict that—where ultimately either you or I have to dominate everything.

25:22 Blackmon: Graham Allison, it’s been a fascinating conversation and a pleasure to have you.

Allison: Thank you for having me.

Blackmon: If you’d like to join our civil conversations about the most urgent issues facing the nation, or to watch this or any other episode of American Forum, visit us at MillerCenter.org. You can reach me directly by email or on Twitter @douglasblackmon. You can follow our guest in this episode @GrahamTAllison. Thanks for watching.

See you next week.