About this episode

December 06, 2017

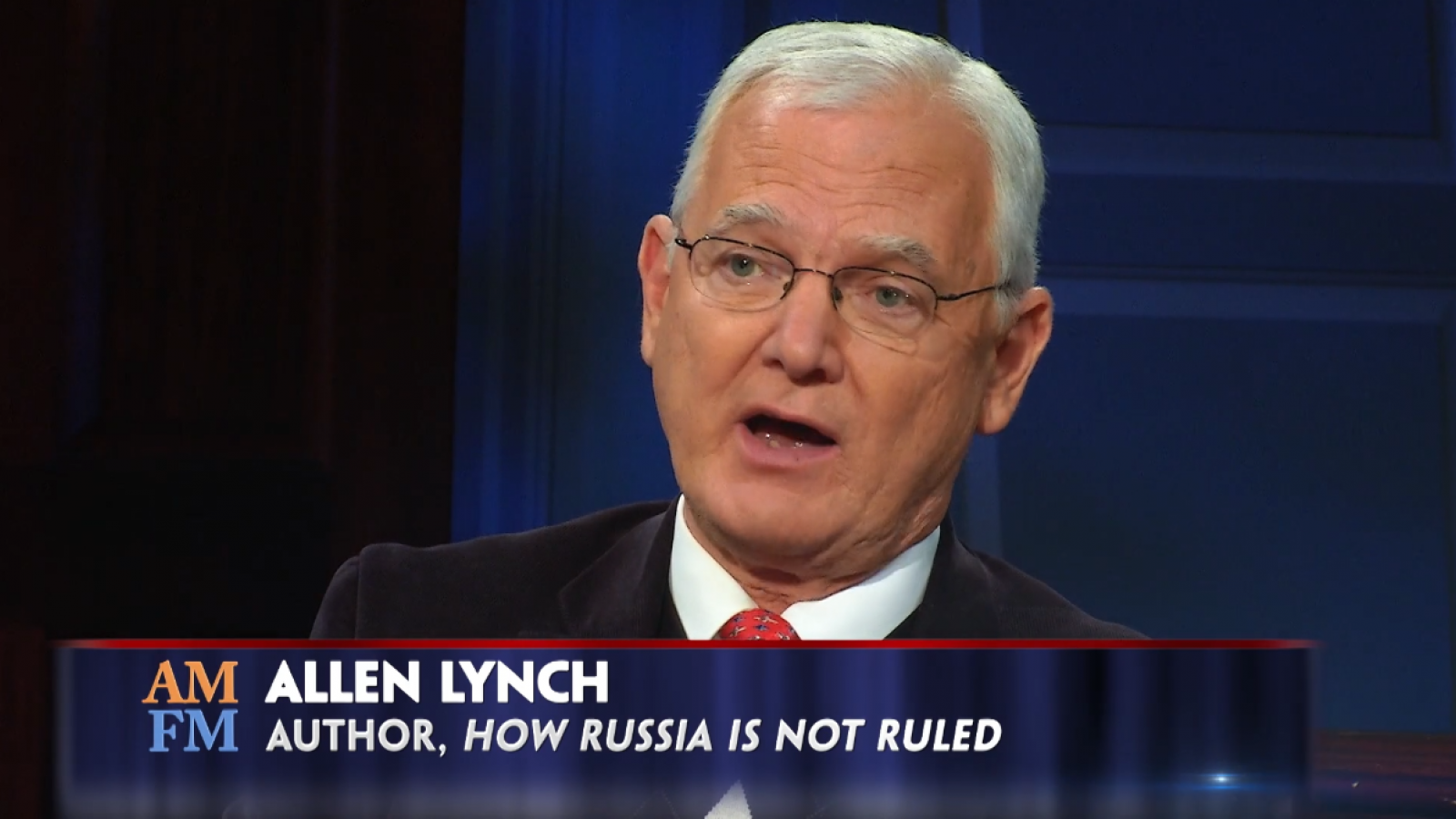

Derek Chollet & Allen Lynch

Hosted by Douglas Blackmon

On December 31, 1999, Boris Yeltsin, president of the young Russian Federation, resigned. Later the same day, Yeltsin’s chosen successor, Vladimir Putin, introduced himself to the world, promising to revitalize his country and its honor. The ensuing two decades have been very different. Putin has suppressed public protest and independent media. Political opponents and critics have been murdered and imprisoned. He has become a strongman ruler. So how does the United States deal with Putin? This week, two experts join us to discuss this question: ALLEN LYNCH is a University of Virginia professor who has researched and written on Russian foreign policy and its politics for many years. DEREK CHOLLET is a top official at the German Marshall Fund of the United States and worked at the Pentagon as a senior advisor, as a special assistant to President Barack Obama, and on the National Security Council staff.

Transcript

00:40 Douglas Blackmon: Welcome back to American Forum. I’m Doug Blackmon. On December 31, 1999, Boris Yeltsin, president of the still very young Russian Federation, resigned, a shocking announcement from that nation’s first democratically elected national leader. In a broadcast watched around the world, Yeltsin apologized to his people for failing to move Russia beyond its “totalitarian past,” and for a decade of painful economic trauma and political upheaval. He said the new, post-communist Russia, needed new leaders and new ideas in a new millennium. Later the same day, Yeltsin’s chosen successor introduced himself to the world.

It was Vladimir Putin, an ex-KGB officer hardened by the Cold War, and frustrated by the national humiliation that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. He promised to revitalize his country and its honor, and at the same to protect Russia’s new “freedoms of speech, thought, and the press.” The ensuing two decades, have been very different. Mr. Putin clamped down on public protest and suppressed independent media. National wealth was plundered by many of his allies. Political opponents and critics have been murdered and imprisoned. He has become a strongman ruler—more consistent with long centuries of Russian history than its brief flourish of genuine democracy. But Putin did restore a sense of international importance and pride to Russia. In 2014, it annexed Crimea and has sponsored rebels fighting to dismember Ukraine. Putin has also given military support to the ruthless Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad in a civil war that has seen rampant war crimes, the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians, created a staggering refugee crisis, and helped destabilize European politics. And Putin has challenged his old nemesis—the United States. Russia’s hack into the emails of the Democratic National Committee and its efforts to influence the 2016 presidential election damaged American confidence in our own democratic systems, and triggered crippling investigations and legal jeopardy for the administration and family of President Donald Trump—and possibly for the president himself. So how does the United States and its national leadership deal with Vladimir Putin? Joining us to discuss that are two experts on Russia, U.S. foreign policy, and Mr. Putin: Allen Lynch is a University of Virginia professor who has researched and written on Russian foreign policy and its politics for many years. Among his books is Vladimir Putin & Russian Statecraft. Derek Chollet is a top official at the German Marshall Fund of the United States. He also worked at the Pentagon as a senior advisor under two secretaries of defense, as a special assistant to President Barack Obama, and on the National Security Council Staff. In 2016, he published a book entitled The Long Game: How Obama Defied Washington and Redefined America’s Role in the World. Thank you both for being here. So let’s go back to that moment in 1999 I referred to in the introduction, where there was such shock in the United States, not—it wasn’t a complete surprise, but nonetheless shock at the end of Boris Yeltsin, and then this person that people in the United States really had, for the most part, never heard of before—certainly most Americans had not—but this person, Vladimir Putin, emerges at what still seems like is supposed to be maybe a re-blossoming, even, of what Russia had been struggling to accomplish in the previous decade. But when you go back to that time, what—was there ever any possibility that a different sequence of events, something more like what people were hoping for in 1999, might have unfolded in Russia? Thank you both for being here.

So let’s go back to that moment in 1999 I referred to in the introduction, where there was such shock in the United States, not—it wasn’t a complete surprise, but nonetheless shock at the end of Boris Yeltsin, and then this person that people in the United States really had, for the most part, never heard of before—certainly most Americans had not—but this person, Vladimir Putin, emerges at what still seems like is supposed to be maybe a re-blossoming, even, of what Russia had been struggling to accomplish in the previous decade. But when you go back to that time, what—was there ever any possibility that a different sequence of events, something more like what people were hoping for in 1999, might have unfolded in Russia?

Allen Lynch: We know that by the end of the 1990s the hopes for a liberal market democratic transition in Russia had largely come ashoal. The economy had fallen by about fifty percent in industrial production. The country was in massive debt to the outside world in ’99. Russia was paying about one fourth of its dollarized GDP in debt payments, principle, and interest to foreign creditors, sovereign and private. It had lost the first war of secession in Chechnya between ’94 and ’96. It had to stand aside and watch as NATO conducted two military campaigns in the Balkans, one in ’95, and Bosnia, the second, against Serbia, whom Russia considered to be kind of a client state, historical ally. Russia, we tend to forget, was nearly a failed state by the end of the 1990s, and, in fact, Putin’s particular scenario for coming to power was the beginning of the outbreak of a second stage of the Russian–Chechen war.

FACTOID: Russia Launched second Chechen war September 1999 after rebel bombings

So, we need to keep that in mind. He was chosen, I think, at the outset to be a kind of sacrificial prime minister, to take the heat for what most Russians thought would be a very unpopular war, as the first war was, in Chechnya. So, this is the situation: Yeltsin also chooses Putin because he thinks Putin can protect Yeltsin when Yeltsin is no longer president, and Putin will stay true to that commitment. The first act he will take as prime minister is to basically sign a decree exempting, pardoning before the fact, Yeltsin and his immediate family from any prosecution.

05:55 Blackmon: And Derek, you know, I’m curious what you think about that, but also could that next decade have been different? Or was Russia essentially too entrenched in this ossified version of itself for much of anything different to have happened?

Derek Chollet: Well, I think that it could’ve been different. I think it is hard to see, and Allen is very correct to remind us of the incredible tumult that Russia faced in the 1990s, not just the problems that Allen’s talked about in terms of the security situation, but the economic collapse, a lot of political turmoil.

FACTOID: Putin joined Yeltsin’s staff in August 1996 as first deputy manager

And when Putin first came into power, he was an unknown. He’d barely been in the Kremlin much at all in Yeltsin’s top staff. And it was initially thought that he could possibly be a stabilizing force. I mean, this was—Yeltsin at the end of his time in office was sick. He was often inebriated. He, in many ways, embodied the sickness that was Russia at the time. And so, Putin came in. He was young. He was vibrant. He—some thought perhaps he would be a technocrat, someone who would embrace the fundamentals of reform, and—but stabilize Russia, to a certain extent. I think in many ways the stories—the story of the 2000s is the slow evolution of American thinking about Putin, and the resignation I think many American leaders came to have about Putin’s fundamental goals, about his core. And I think, sure, the United States could’ve done things differently here and there throughout that period, but I don’t know, given what we know today of Putin, and what he was really about, and what he remains about, that we could’ve changed things fundamentally.

07:37 Blackmon: And the—but—and that in the end, though—and Allen, I think you’ve written this or said this in the past—if he weren’t there, the alternatives to him now might be arguably much, much worse.

Lynch: Well, I think there’s two stages to that issue. The first is if we take his first seven or eight years in office, from, let’s say, 2000 to 2008. Putin actually did solve some very real problems that Russia had been facing emerging from the 1990s as a quasi-failed state. He managed, for example, not simply to be the beneficiary of rising oil prices, but to establish special state funds where he was able to put away enough of those profits to be able to use, for example, to pay off all of Russia’s sovereign debt by 2005, right? By 2008, when the world economic crisis occurred, Russia had the third largest hard currency reserves in the world, after China and Japan, and they were able to use that to avoid a collapse of the kind that afflicted both Gorbachev in the late ’80s and Yeltsin in the late ’90s when oil prices fell comparably. So, living standards rose. The economy grew by seven to eight percent per year on average for almost eight years. So those were significant accomplishments. And he rebuilt the state. He won the war in Chechnya that Russia had lost. He reestablished a degree of coherence to the military. Look at the war, however clumsily, but nevertheless won, in Georgia in August of 2008. However, the manner in which he went about solving these problems and building that state, using essentially networks of old cronies from the intelligence networks, from the military, police, and old boy networks from his hometown of Leningrad/St. Petersburg, resulted in the construction of a state too highly centralized, too nontransparent, too corrupt, and, in a way, in 2017 the Russian economy, having exhausted the productive resources it inherited from the Soviet Union now have to face the challenge both of reforming the economy but also reforming the political system at the same time. That brings us back to the situation of the Soviet Union in the late ’70s and early 1980s, and if anything condemned Gorbachev to failure, it’s when he attempted to reform simultaneously the economy and the political system.

FACTOID: Russian GDP in 2013 was $2.2 trillion, then fell to $1.3 trillion in 2016

09:50 Blackmon: Maybe that’s what I’m trying to get at, not to belabor it, in terms of what might have been different, that in the end he does have some resources, he does solve some problems that were very severe, but in the end—and might that—had that gone in a way that actually led to a more diversified economy, with some sort of transparency, maybe the road to a genuine, modern, functioning economy would’ve been—at least the beginnings of it might’ve been found.

Chollet: I think a different path was there, available to him. It was certainly a path that the United States and our European partners tried to help him find throughout the years. It was widely acknowledged that he was over-reliant on fossil fuels, despite the fact that he was able to use many of those resources to bring some stability to the country. And I think that’s one of the great tragedies of this era is that despite the best efforts of the United States and its partners to try to work with Russia, bring Russia in as a partner, to do all sorts of things—fight terrorism, bring stability or ensure stability in Europe—we ended up failing. And it was despite our best efforts. And I think there was a debate inside Russia about the course that they should take, and we’ve seen a period where Putin stepped away from the presidency, back into the prime minister-ship, under Dmitry Medvedev, when he was the president from 2008 to 2012, where there was a different face on Russia. It was a less confrontational face, one where the United States and Russia got a lot done. So, I think this path was available to them. I think the tragedy for the Russian people, ultimately, will be I don’t see Putin playing a very smart long game. I think Russia’s a declining power. I don’t think Putin has done much to reverse that decline, and, in fact, if anything, many of the decisions he’s made over the years have only accelerated it.

11:40 Blackmon: What is the—Putin’s case for that it’s not his fault and it’s not Russia’s fault, it’s really America and the West.

Lynch: Well, the argument that—of which Putin is absolutely convinced, and the Russian national security elite is absolutely convinced, is that, indeed, the United States and Germany in 1990 promised Gorbachev that in exchange for unifying Germany rapidly, and in NATO there would be no NATO expansion, and they quote James Baker to Gorbachev saying NATO will not move, quote, “One inch eastward.”

FACTOID: Baker served as secretary of state under George H. W. Bush, 1989-92

The question is: what does that mean? The American officials at the time say that meant no NATO troops in former East Germany. That commitment’s been kept. Remember, at the time the Soviet Union still existed. No one was yet thinking about its disintegration. And its Warsaw Pact military alliance was still intact. However, the subsequent history of NATO expansion in the 1990s and into the 2000s has basically reinforced the Russian narrative that what the United States has done is betray the substance of that commitment, which was that U.S. and NATO would not increase their security at the expense of Russian security. In effect, the United States chose to design the post-Cold War architecture for European security in terms of NATO, which, whatever your intentions, leaves Russia on the outside. Leaving Russia on the outside is simply not acceptable for Russia’s national security elite, and they have now turned that into a narrative of betrayal, even to the point of delusion, arguing that the United States was somehow conspiring for the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1990 and 1991. When you read the record, the exact opposite was happening. Actually, at the one moment in world history when the United States could have acted to accelerate Soviet disintegration, George Bush embraces Gorbachev, he embraces the Soviet Union, he warns the Ukrainians to abandon the temptation of suicidal nationalism in Kiev, August 1, 1991. So, again, the fundamental sources of the problem are internal.

FACTOID: Despite Bush’s speech, Ukraine voted for independence 92% to 8%

13:42 Blackmon: And then we get into the Obama years, and there is a kind of desire, an enthusiastic desire, to make something happen, but at a point in time where one wonders whether the U.S. diplomatic understanding of the—of what was happening in Russia, or what its actual desires were, was an accurate one. But over the—over the span of all that time, yes, the Russians are the primary authors of their own problems, but you don’t have the sense that the United States has been particularly brilliant in its handling of Russia, either.

Chollet: You go—have to go back to where this started, which was the end of the Cold War. And Putin has been very clear in the last several years about what he thinks of the end of the Cold War, and the humiliation that I think Russia still deals with about the way the Cold War ended, and the fact that Russia, in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, or for the decade after the Cold War, was under immense turmoil. The United States wanted a partnership with Russia. I think George H. W. Bush hoped that a different Soviet Union, and then after the Soviet Union collapsed a capably led Russia could be a partner for the United States. James Baker believed that the Cold War ended, in his mind, in August of 1990, when the U.S. and the Soviets stood side by side to condemn Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the first time the superpowers had lined up on the same side for what, during the height of the Cold War, would’ve been a recipe for a superpower showdown, right? [Blackmon: Yeah, unimaginable, right.]

FACTOID: Operation Desert Storm launched January 1991, Kuwait liberated February 27

Unimaginable. So, I think the hope was that, for George H. W. Bush, was that the United Nations—that he, of course, had served as the ambassador to the United Nations in the 1970s—that system could actually work. The U.S. and the Soviets—and the U.S., later, and the Russians—could work together with other world powers to help achieve common interests and goals.

Fortunately, that reality had to confront another reality, which was the turmoil inside of Russia, and I think one of the interesting dynamics from a U.S. perspective is even though our goal of trying to find ways to partner with Russia on various things was a constant, I would say, from Bush forty-one, to Clinton, to Bush forty-three, through Obama, one of the trends that you see going across administrations is over time resignation of the fact that the U.S. had very little leverage over Russia to help on its own domestic scene, and we didn’t have the capacity to help them in terms of their economic woes. There wasn’t a Marshall Plan that was available to us. You have to remember, George H. W. Bush, probably at the moment where U.S. support could’ve been needed most, he was in no position to offer Russia a massive assistance package.

FACTOID: U.S. spent $12 billion to rebuild Western Eruope economically after World War II

There was no shortage of efforts in the Clinton administration to try to send our best economists over to Russia to try to help them reform their economy. But this has been a very, very difficult process, and it’s one ultimately, we were—we have been unsuccessful at. And I think our democratic hopes for Russia, the hope that Russia could be stable with itself, at peace with itself and its neighbors, could have a functioning economy that’s diverse, we’re—we’ve resigned that that’s a long ways off, and we have very limited capacity to do anything about it.

Lynch: Talking about Obama administration policy—and Derek worked in the Obama administration—I think they came to the Russia question convinced that actually the U.S. bore its share of responsibility for the decline of the relationship, perhaps having pressed Russia a little too fast, a little too far, toward its borderlands, especially the promise that one day, Georgia and especially Ukraine would be members of NATO. And I think they very self-consciously approached the Summit in Moscow in July of 2009 with a sense that we need to reconsider the way in which we approach Russia in the sensitive historical borderlands if we’re going to make progress in other areas, like nuclear arms control, dealing with Iran, international economics, terrorism, and so forth.

FACTOID: Obama called for a “reset” of U.S.-Russia relations in Moscow

And actually, the Summit meeting and its aftermath produced quite a significant number of results, including a major transportation network coming into and out of Afghanistan through Russian territory. Now, having said that, the truth is Russia was simply not that important enough to the United States on a global focus. American focus is global, not regional, as is Russia—as is Russia’s. And the Obama administration’s attention turns elsewhere, including always domestic affairs. China’s much more important than Russia. The Middle East is much more important than Russia. And, ultimately, the Russians discover once again that their hopes for Washington’s recognition of Moscow as an equal simply cannot be met. That’s a recurrent theme, and Russian frustration is a recurrent theme.

18:32 Blackmon: And so, then we have this change, where, you know, for that period of time the problem is that this guy’s crossing borders, and is using military forces in these unacceptable ways, you know, civilian airliners shot down out of the sky, you know, this—you know, really horrifying physical violence is how Putin is pursuing whatever his ambitions are. And now we switch to the last eighteen months, and it’s a very different kind of Russia that’s on our mind. It’s this extraordinary capacity it seems to have infiltrated our—not just our electoral system, but our cultural infrastructure, and in a way that seems to have actually had an impact. But so, is that a coherent shift in strategy, or is that just a blossoming of a strategy that’s been there forever? Or is it that the—just a sort of stumbling that, you know, in the course of trying everything that he can sort of think of, this one stumbles into being what turns out to be an extraordinarily effective way of making Americans have doubts about our own democratic system?

Chollet: I think what’s different is it probably says more about us than about them. I don’t think—they’re showing some technical capability, but I don’t think it’s so much about their expertise; it’s about our own internal weakness, or lack of understanding or awareness of our own vulnerabilities.

FACTOID: Russia’s “Fancy Bear” hackers stole Clinton, DNC campaign emails in 2016

They were successful in meddling with the election. I don’t think it affected the outcome, but it absolutely is helping to fuel the poisonous politics that we have here in the United States. I think that was partly—that was Russia’s intent, certainly. They’ve gotten lucky along the way. They never in a million years imagined that Donald Trump would get the traction that he got and that he would be president of the United States, and he, in effect, has helped, aided, and abetted their efforts. I don’t know that that was collusion or not; we’ll find that out as Robert Mueller (laughs) does his investigation. But there’s no question of where their intent is, and that they have had a strategy that they’ve been trying to implement. They have developed their skills. But they’ve also gotten lucky.

Lynch: I would say that interfering in the American election in the ways that it looks like the Russian government did was a big thing. It was not a point of continuity in Russian–American relations in the past. It, I believe, reflected Putin’s conclusion that there was basically nothing further to hope for in the relationship. He fully expected that Hillary Clinton would win, and he accepted that her administration would be the third term of an Obama administration, and would resume a full-court press on his political system at home, on his client states abroad, in the form of a campaign democratization, human rights, which he interprets as regime change, directed against his regime and his allies most of all. So, I believe the decision was taken—and only he could have approved it, because it’s so momentous and so risky and so portentous—that it reflected the collapse in the expectation for the relationship. And not to elect Donald Trump. There’s nothing in Putin’s record that shows him—although he can take risks, but not for such an improbability. But to take the risk to so embarrass the American political system, to expose double standards, to undermine American attempts to use U.S. soft power to undermine his hard power, that was a risk that he could take. That was a stake worth taking that risk for. The stupendous irony is, however, that with the unexpected election of Donald Trump, that interference has rendered it impossible to even conceive of significant movement in Russian–American relations for the long foreseeable future. You have a bipartisan, overwhelming vetoproof majority now on the left, as well as on the right, mobilized on an anti-Russian basis, and it’s just evidence of the irony of history, but also, perhaps, of the desperation of Putin in resorting to such a measure at that point.

22:38 Blackmon: All right, so now the back—let’s go back to a more theoretical sort of level. Both of you have talked about some of these things, but give us a—given all of this, given that you’re both patriots, no matter what your politics are, if the—if you had the opportunity now to sit down with President Trump, or someone else who—very close to him, and you were to say, “Look, I’m not on your side necessarily politically, but I still want the country’s relations with Vladimir Putin to be the best that they can be, for the—a success for our country.” What would your—Derek, what would your counsel to the president or that person be?

Chollet: Well, we have to—when we’re dealing with Russia, we have to always start from a position of strength. Donald Trump talks a lot about strength. “Mr. President, you understand the importance of strength, but a key part of strength in terms of dealing with Russia is the strength of our alliances and our partnerships. That—you’ve got to get that right first in order to be able to try to do anything constructive with Russia.” And so, I would advise him to do many things that he’s not doing to try to strengthen those alliances and partnerships. But beyond some discrete issue areas, Russia is not much interested in being a very constructive partner with the United States when it comes to trying to solve big global problems. It’s a relatively weak country. It’s got a relatively small economy. It’s got a lot of internal problems. And so, in some ways, we need to expect less of this relationship.

Lynch: I think instead of trying for the best, let’s avoid the worst, things like reinforcing cooperation between Russian and American militaries in Syria, to avoid air crashes or incidents on the ground.

FACTOID: Russia backs Assad regime forces against U.S. supported rebels

Maybe try to lower the intensity of naval and air operations and ground operations on both sides of the Russian–NATO borderlands. Very sensitive business, and there have been some very hair-trigger situations in the last three years. Maintaining a very tenuous dialogue with Russia, as well as China, about North Korea’s ambitions, all right? And maybe beginning a longer-term process, reinstituting many of the official and backchannel dialogs that were characteristic throughout the worst periods of the Cold War after the Cuban Missile Crisis. It’s not as dangerous as those times. There’s no real danger of a nuclear war developing over a further deterioration in Russian–American relations. But what I think is worse than the Cold War: at no time since ’62 have I seen Americans and Russians less interested in actually listening to each other.

Blackmon: Allen Lynch, Derek Chollet, thanks for being here.

Chollet: Thanks.

Lynch: You’re very welcome.

Blackmon: If you have more questions about Vladimir Putin or U.S.–Russian relations, visit MillerCenter.org, where you can find new articles by both of our guests today, along with a host of other expert insights and highlights from our recent three-day symposium on the 200-year history of U.S. and Russian diplomacy. You can also reach me to discuss any of the most complicated issues facing our country using the email shown on your screen, or on Twitter, @douglasblackmon. Derek Chollet is also on Twitter, @derekchollet. Thanks for watching. See you next week.