America's Vietnam

President Eisenhower was determined to keep the United States out of the French war in Vietnam

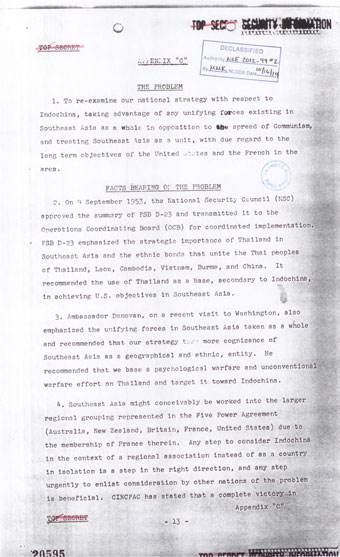

In the 1950s, American strategists viewed Asia as the most dangerous and unstable theater of conflict with the Communist bloc. In Korea, in Taiwan, and in Southeast Asia, Americans perceived dangerous threats to the “free world.” And nowhere did the stakes seems higher than in Indochina.

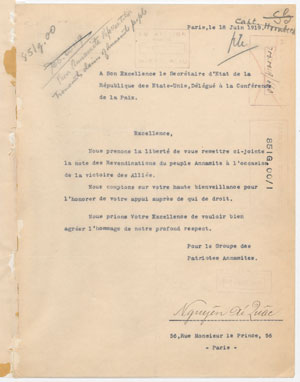

Indochina had been France’s Asian jewel since the 1880s. Not only did it produce rice, rubber, tea and coffee, coal and zinc, but the colony demonstrated France’s great power status. During the Second World War, the Japanese conquered Indochina, but in 1945, the French government immediately set out to reclaim its colonial possession. It was not so easy. France’s plans were foiled by a powerful Vietnamese anti-colonial movement that had been much fortified during the war, and was led by the well-educated and worldly Communist Ho Chi Minh. In 1945, France began a military campaign to suppress the rebellion, inaugurating thirty years of bitter conflict in Vietnam.

Initially, American leaders looked warily at France’s re-conquest of Indochina, but with the triumph of Mao’s Communist revolution in China in 1949 and the outbreak of war in Korea just eight months later, the Truman administration came to see French Indochina as a front in the global war against Communism. By 1952, the United States was paying for at least half the cost of France’s war there. President Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles believed, as Dulles put in a speech in early 1953, that the Soviets wanted to control “Indochina, Siam, Burma, Malaya … what is called the rice bowl of Asia.” Ike agreed that keeping Indochina from falling to the Communists remained essential to America’s national security.

But how? In the middle of 1953, Eisenhower managed to secure an armistice in Korea, ending a dismal, costly and unpopular war there. He did not want another Korea, and remained determined that America would stay out of the French war in Vietnam. His solution: give France more money and weapons to fight the Communists so American soldiers would not have to do it. In a speech on August 4, 1953 in Seattle, he told his audience why he was so concerned with Indochina. “If Indochina goes, several things happen right away,” he claimed. India would be “outflanked;” “Burma would be in no position for defense,” and “how would the free world hold the rich empire of Indonesia? ... So you see,” he concluded, “somewhere along the line, this must be blocked and it must be blocked now, and that’s what we are trying to do.”

Excerpt from Eisenhower's remarks at the 1953 Governor's Conference in Seattle

The U.S. Army had already run the numbers and concluded it would take seven army divisions and one marine division to defeat the Viet Minh [Communist guerilla forces in South Vietnam]. Along with support and logistic personnel, that meant sending 275,000 men to Indochina. Just months after halting a most unpopular war in Korea, Eisenhower clearly had no appetite for such a dramatic move.

‘The Age of Eisenhower,’ chapter 8

But when the French forces found themselves caught in a death struggle with Communist forces at a northern outpost called Dien Bien Phu in the spring of 1954, Eisenhower faced a terrible dilemma. Should he send Americans in to aid the French and halt a Communist victory in Vietnam? At the start of 1954, Eisenhower told his advisers “he simply could not imagine the United States putting ground forces anywhere in Southeast Asia…. There was just no sense in even talking about United States forces replacing the French in Indochina. If we did so, the Vietnamese could be expected to transfer their hatred of the French to us. I cannot tell you, said the President with vehemence, how bitterly opposed I am to such a course of action. This war in Indochina would absorb our troops by divisions!”

But it wasn’t an easy call. The French begged the Americans for more aid and the use of aircraft to bomb Communist positions at Dien Bien Phu. Most of Ike’s advisers, from Vice-President Nixon to Admiral Arthur Radford, wanted to intervene militarily. John Foster Dulles pushed Eisenhower to be more aggressive. Some of Ike’s critics at home felt he was going soft in facing the Communist threat. Eisenhower chose to stay out of the conflict in 1954.

Only a few months back we had both [General} Chiang [Kai-shek, president of the Republic of China, who had ] and a strong well-equipped French army to support the free world's position in Southeast Asia. The French are gone—making it clearer than ever that we cannot afford the loss of Chiang unless all of us are to get completely out of that corner of the globe. This is unthinkable to us—I feel it must be to you.

Eisenhower to Winston Churchill, February 19, 1955

Even so, Eisenhower did not want to appear indifferent to the Communist threat in Asia. Just a day after telling the NSC that “there was no possibility whatever of U.S. unilateral intervention in Indochina,” Eisenhower strode into the Indian Treaty Room in the Old Executive Office Building on April 7, 1954 for his usual weekly press conference. In some of his most famous words, he asserted the viability of the domino theory. In Vietnam, he said, “you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the ‘falling domino’ principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.” He went on to say that “the loss of Indochina, of Burma, of Thailand, of the Peninsula, and Indonesia following… now you are talking really about millions and millions and millions of people.” He concluded darkly: “The possible consequences of the loss are just incalculable to the free world.”

What did this mean for U.S. policy in Asia? Eisenhower avoided a direct military intervention in Indochina in 1954, and the French went down to defeat to the Communist forces in northern Vietnam. But Ike was determined not to allow another such fiasco. Following the partition of Vietnam into a communist North and pro-western South, Eisenhower chose to invest huge sums of money and prestige in transforming South Vietnam into a showcase of a new “free Asia.” Spending billions of dollars, sending military advisers, supporting the increasingly brutal tactics of the South Vietnamese regime of Ngo Dinh Diem—all this effort would help create a pro-American bastion in Southeast Asia and halt Communism. Yet it also left a terrible decision for his successors, once South Vietnam faced a new war with Communist forces.

Ike managed to avoid an American war in Vietnam during his two terms. But he invested so much American prestige and effort in the success of South Vietnam that by the end of the 1950s, America had become deeply invested in its fate. Eisenhower created an American Vietnam, and his successors would wage a bitter – and failed – war to keep it.