The Washington brothers abroad

George Washington's only trip overseas was to Barbados with his brother Lawrence. How did the voyage, and his brother, influence him?

Lawrence Washington was ill.

He had sought cures for his pulmonary disorder (likely tuberculosis) in England as well as at the Warm Springs in what is now West Virginia.1 But his efforts were to no avail. By the fall of 1751 he was ready to consider a desperate plan. Leaving his family behind—a wife and infant daughter—and willing to risk weeks on the open sea during hurricane season, he would try the air of Barbados, or perish.

Thankfully, Lawrence did not have to travel alone. His half-brother George, then only 19 years old, accompanied him. George likely considered it a duty to the brother who, in the wake of their father Augustine Washington's death eight years earlier, had been like a parent to him. But it was also an opportunity for adventure and social advancement. The younger's time-worn diary of the journey—now featured in a new edition by The Washington Papers—offers a glimpse into the brothers' relationship. Not only does the Barbados voyage underscore George's obligation and devotion to Lawrence, but it also reveals a man on the rise.

Military and sea life

Ten years before the Barbados trip, Lawrence, too, was on the cusp of manhood and about to undertake a dangerous sea voyage. In 1740 during the War of Jenkin's Ear, a conflict between England and Spain, 22-year-old Capt. Lawrence Washington cruised to the Indies. He was the newly appointed captain of a Virginia company destined to serve under Adm. Edward Vernon at Cartagena in March 1741.2 Undoubtedly, his 9-year-old brother back home wondered about Lawrence's adventures at sea.3 In a letter from Jamaica in May 1741 to their father, Lawrence alluded to his next "secret" mission: "some talk of the Havanna others Panama, some Cavera-Cruz but perhaps others more probably St Jago de Cuba."4 The very allure of foreign places may have inspired young George to consider a naval career. In fact, by 1746 Lawrence was encouraging the possibility, but George's mother, Mary Ball Washington, was dead set against it. His uncle, Joseph Ball, settled the matter: at sea "they will . . . Cut him & Slash him and use him like a Negro, or rather, like a Dog."5

By the time George sailed to Barbados in 1751, he had likely heard his brother's tales and was braced for difficulty.

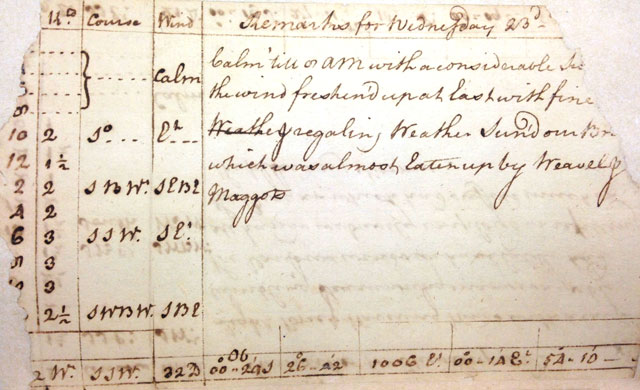

Lawrence was by no means indifferent to the sobering reality of life in the military, especially at sea. Following the Cartagena expedition, he wrote in the same letter to his father, "War is horrid in fact, but much more so in imagination; We there learn'd to live on ordinary diet, to watch much, & disregard the noise, or Shot of Cannon." The tropical climate was another struggle: "We are all tired of the heat & wish for a cold Season to refresh our blood."6 By June 1741, even his admiral was complaining that the "fiery-breeze Season" had greatly deterred naval operations.7 By the time George sailed to Barbados in 1751, he had likely heard his brother's tales and was braced for difficulty. He was not surprised when, well into the outbound voyage, their food provisions had been compromised ("almost Eaten up by Weavel & Maggots"). He also readily employed local terminology perhaps learned from his brother. On the return voyage, George noted that "A Fresh gale (or what in this part of the World is called a fiery Breeze) hurried us pass the Leeward Islands."8

Education and social connections

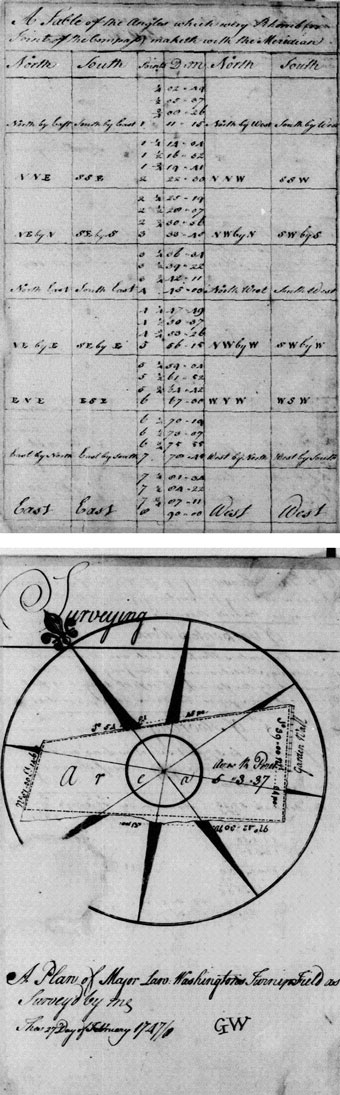

The beginning of the Barbados diary manuscript is written in the form of a ship's log, in which George recorded the position of the brothers' vessel on each of the 35 days for which entries survive. It clearly reveals more of Lawrence's hand in George's life. Lawrence had received a proper English education, back when his father was alive and he and Lawrence's mother, Jane Butler Washington, could afford it. George had no such benefit and did his studying at home. Lawrence, however, appears to have been a good influence. His library included titles such as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and James Atkinson’s Epitome of the Art of Navigation, the latter of which featured in George's school exercise books.9 Atkinson's text, which appeared in myriad editions throughout the first half of the 18th century, contained a sample logbook of a voyage to Barbados, and George reproduced verbatim the text's "Table of Angles"—a rendering of the 128 compass directions—in his notebooks, right alongside a practical survey of Lawrence's turnip field. Certainly, the study of navigation, with its emphasis on trigonometry, had much to bear on George's future as a surveyor.

In addition to his role as mentor, Lawrence's relationships with elite Virginians also favored George's early development. Through his marriage to Ann Fairfax in 1743, Lawrence forged an alliance with one of the leading families of Virginia. His father-in-law, William Fairfax, was the first cousin of the colony's leading landholder, Thomas, sixth Lord Fairfax. George Washington's first professional surveying assignment, the beginning of a lucrative career, came by way of the Fairfax family. Indeed, as DAR Library Reference Librarian Kiera E. Nolan observes, "It was through his brother's steadily growing influence and powerful connections that George Washington was able to start getting a foothold in a world that otherwise would have been completely unattainable to him."10 Little did he know that his world was about to expand to include West Indian high society.

Barbados

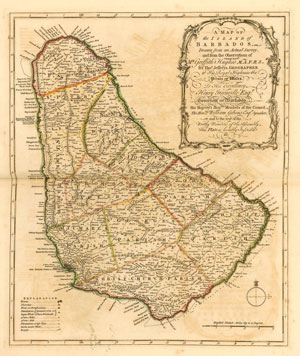

It was most likely a Fairfax connection that led to the brothers' Barbados voyage. William Fairfax had relatives on the island. His wife, Deborah Clarke Fairfax, was the sister of Gedney Clarke, Sr., who was an influential member of Barbados' planter elite. In addition to owning a townhouse and a plantation on the island, he also possessed land in Virginia's Northern Neck, granted by Lord Fairfax. Clarke and his family would host the Washington brothers on numerous occasions during their visit. William Fairfax could also speak knowledgably about Barbados and its offerings as a subscriber to Griffith Hughes' 10-volume The Natural History of Barbados, published in 1750. George knew of the work, referred to it in his diary, and may have encountered it in Fairfax's library at the Belvoir estate. Lastly, William Fairfax's son-in-law, John Carlyle, owned a brigantine, the Success, which was just about to depart for the island from the Potomac River. Its imminent sail date in the fall of 1751 may have prompted the timing of George and Lawrence's voyage, though it still cannot be proven that they sailed on the vessel.11

During his seven-week stay in Barbados, when he was not convalescing from smallpox contracted there, George rubbed shoulders with both political and military elite. He dined with governors, judges, and commanders. He investigated Charles Fort at Needham's Point in Bridgetown, and he commented more generally that the island "ha[d] large Intrenchments cast up where ever its possible for an Enemy to Land and may not (as nature has greatly assis[t]ed) improperly be said to be one entire fortification." He was impressed that the militia was larger than "in Jamaica & all the other Leewa[rd] Islands." In short, he wrote at the end of his stay, "The Governor of Barbado's seem[s] to keep a proper State."12 Already, important matters of government and defense were of interest to him.

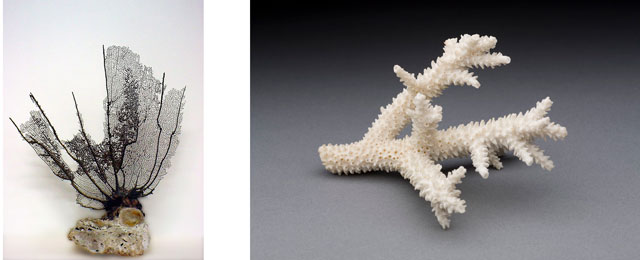

Though Lawrence remained on the island and George returned to Virginia in early 1752, the influence of George's elder brother and perhaps letters of recommendation from significant Barbadians impressed Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie, who met with the young man upon his arrival and asked about Lawrence's health.13 In June George was so bold as to inquire of Dinwiddie about a military appointment, and by the end of the year he would be commissioned as major and adjutant for the Southern District.14 Lawrence was dead by July, and Mount Vernon, named after his commander, eventually passed to George. There, two specimens of fan and staghorn coral, possible souvenirs from their adventure in 1751–52, remain among the collections to this day.

With special thanks to Lynn A. Price for contributing research to this piece. George Washington's Barbados Diary, 1751–52, ed. Alicia K. Anderson and Lynn A. Price (University of Virginia Press), will be available by May 2018.

1. W. W. Abbot et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (Charlottesville, Va., 1983–95), 1:39; and General Ledger A, 1750–1772, Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers, folio 4, left.↩

2. Commission of Lawrence Washington, June 9, 1740, Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union. See also Lawrence Washington to Augustine Washington, May 30, 1741: "If the Sailors can claim much honour I pertake of it as Capt. of the soldiers who acted as Marines" (Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union).↩

3. George Washington's later teenage reading would include travel literature. He signed, in his youthful handwriting, copies of Andrew Michael Ramsay’s The Travels of Cyrus . . . (London, 1745) and Daniel Defoe’s A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain . . . (London, 1748). See Appleton P. C. Griffin, comp., A Catalogue of the Washington Collection in the Boston Athenæum (Cambridge, Mass., 1897), 67, 170. ↩

4. Lawrence Washington to Augustine Washington, May 30, 1741, Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union. ↩

5. Jared Sparks, ed., The Writings of George Washington . . . (Boston, 1833–37), 2:415–16; Joseph Ball to Mary Ball Washington, May 19, 1747, quoted in Philander D. Chase, “A Stake in the West: George Washington as Backcountry Surveyor and Landholder,” in George Washington and the Virginia Backcountry, ed. Warren R. Hofstra (Madison, Wis., 1998), 162. ↩

6. Lawrence Washington to Augustine Washington, May 30, 1741, Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union.↩

7. Original Papers Relating to the Expedition to Carthagena (London, 1744), 147–48.↩

8. See George Washington's Barbados diary entries for Oct. 23 and Dec. 24, 1751 (Library of Congress, George Washington Papers).↩

9. See “An Inventory of the Estate of Lawrence Washington Esqr. deceased, as Apprais’d by us the Subscribers the 7th & 8th of March 1753” (Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union). George Washington's Exercise Books, 1745 to 1747, are in the George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.↩

10. Kiera E. Nolan, "Lawrence Washington," Mount Vernon Digital Encyclopedia: http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/lawrence-washington/.↩

11. See Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington (Charlottesville, Va., 1976–79), 1:26; and P.R.O.: C.O. 5/1445, folios 58–59, 63; 1446, folio 54, Naval Office Shipping Lists for Virginia.↩

12. See George Washington's Barbados diary entry for Dec. 22, 1751 (Library of Congress, George Washington Papers).↩

13. See George Washington's Barbados diary entries for Jan. 30–Feb. 2, 1752 (Library of Congress, George Washington Papers).↩

14. W. W. Abbot et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series (Charlottesville, Va., 1983–95), 1:51, 53.↩