Origins of the Modern American Presidency

The presidency, penned Alexander Hamilton in 1788 following the tumultuous Constitutional Convention, should be “energetic” for good government to exist. But what “are the ingredients which will constitute this energy,” he asked in the Federalist #70. “How far can they be combined with those other ingredients which constitute safety in the republican sense? And how far does this combination characterize the plan which has been reported by the convention?” Hamilton concluded that energy in the executive needed to be combined with “a due depended on the people and a due responsibility.” 1 But, though Federalists and Anti-Federalists would continue to debate the strength of the federal government versus the rights of the states and the individual, they could agree on the establishment of an executive branch that would be equal, if not subordinate, to the legislative branch. The president would be “Our Fellow-Citizen of the White House,” who would hold “office hours” with citizens who could visit the White House and comment on his performance. As a result, the early American presidency had a small staff and a “personalized office” and the White House itself had become a “ramshackle building that was showing its age by the end of the nineteenth century.” 2

As historian Lewis Gould notes, party politics notably set apart the nineteenth- and twentieth-century presidency. Rather than becoming a “Citizen-in-Chief,” nineteenth-century presidents bestowed patronage, adhering to the “mores of the party” and giving “heed to the council of Republican and Democratic elders.” 3 Winning the presidency meant federal jobs for loyal party workers. Moreover, as historian Gil Troy notes, the president himself did not actively campaign for the nomination. 4 Though he frequently pulled strings behind the scenes to secure it, the idea of the “public servant called to office” shaped cultural expectations of the American presidency. Though Troy argues that this was more an ideal than a reality, the culture of honor and public service of the early republic influenced rhetoric and campaign strategies for those seeking and winning the presidency.

This section offers a look at the origins of the modern American presidency. Debates about the institution in the early republic and the nineteenth century set the rules and parameters that modern presidents—from Theodore Roosevelt to Barack Obama—would at times challenge and reconfigure, and at other times, accept and adapt. By the twenty-first century, presidents would be labeled as the “most powerful individual in the world” and their every private and public action and utterance would be analyzed, dissected, and criticized. But, this transformation involved changes in the institutional authority of the executive branch, communications technologies, electoral procedures, and voting demographics over the course of the twentieth century. Going back to the origins of the American presidency and its limited role in American political life during the nineteenth century illuminates how dramatically the political, cultural, and economic role of the modern president changed over the course of the twentieth century—the historical focus of this website.

The 1800 Election: Competing Visions for the American Presidency:

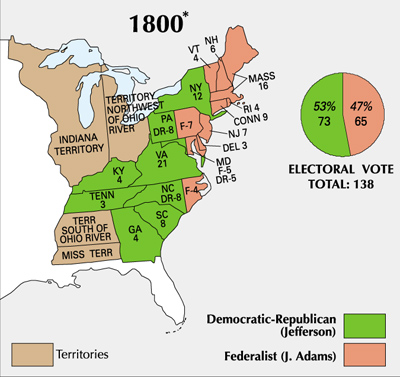

The presidential election of 1800 was bitter and polarizing. The candidates—incumbent president and Federalist John Adams and the Democratic-Republican challenger Thomas Jefferson—hurled personal attacks against one another as they both claimed the survival of the newly founded Republic was at stake.

With pockets of support across the North, Adams espoused a belief in a strong central government with an economic future in commerce and foreign trade. Jefferson countered this vision with a belief that the future of the newly joined United States of America was in the countryside where yeomen farmers could sustain themselves. The farmers in the slave-holding South and on the western frontier agreed with the Democratic-Republican.

The campaign became personal and bitter. In what historian Jeffrey Pasley calls, “newspaper politics,” each side used the press to attack one another. Adams went so far as to use his executive power to pass the Sedition Acts to prosecute printers who spoke out against the Federalists. 5

Each side maneuvered within an uncertain and non-uniform system of presidential electors to win the presidency. Though Thomas Jefferson beat John Adams 73 to 65 in electoral votes, electors did not distinguish between their presidential and vice-presidential selection, resulting in a tie between Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr. The race moved to the House of Representatives, and after six days of vote casting, Thomas Jefferson finally gained the majority to win the presidency. When presidential leadership passed from one party to another, the newly elected president called the bitter contest the “Revolution of 1800”—as power shifted from one party to another without shattering the newly founded republic. Pasley, however, argues that the election was not so much a revolution of government, but of political culture towards a more popular politics.

Though George Washington famously warned for the country to avoid party politics in his 1796 “Farewell Address,” the 1800 election demonstrated the propensity toward organizing around factions, with each faction espousing a different ideological interpretation of the Constitution. Following that election, new rules established the defining parameters of the “presidential game.” 6 The Twelfth Amendment (1804)—which clarified the rules for the Electoral College selection process by establishing a unified ticket for the presidential and vice-presidential nominees (rather than the vice-president being determined by the runner-up to the presidency)—set the stage for the party politics that would dominate American political life over the next century.

The Election of 1800 provides a window into debates about the role of the American presidency and the ways in which Americans should elect the individual to this office. Though the Constitution outlined the broad parameters for the election to office and the responsibilities of the office, the Founding Fathers debated how the vague and uncertain rules in the Constitution should be applied. As historian Joanne Freeman argues, “democracy was a problem in the early republic,” and the “real question at the heart of the period’s politics was precisely how democratic a republic America should be.” 7 The early republic was “underdeveloped and unsteady, a political experiment with an uncertain outcome,” and as the election of 1800 demonstrated, a climate of crisis surrounded every debate about the American presidency as republican ideals conflicted with democratic realities.

Suggested Reading:

SECONDARY SOURCES

- Joanne B. Freeman, “Explaining the Unexplainable: The Cultural Context of the Sedition Act,” in The Democratic Experiment: New Directions in American Political History, ed. Meg Jacobs, William J. Novak, and Julian E. Zelizer, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 20–49.

- Jeffrey L. Pasley, “The Devolution of 1800: Jefferson’s Election and the Birth of American Government,” in America at the Ballot Box: Elections and Political History, ed. Gareth Davies and Julian E. Zelizer, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015).

PRIMARY SOURCES

- The Constitution of the United States of America

- President George Washington’s Farewell Address, 1796

- Federalist No. 70. Alexander Hamilton, “The Executive Department Further Considered,” March 15, 1788.

- The Election of 1800 Primary Source Collection by the Library of Congress

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What different visions existed for the functions and responsibilities of the American presidency?

- What do these contrasting visions illuminate about the debate between republicanism and democracy?

- Why does George Washington view factions as dangerous? Does the election of 1800 prove his prediction right or wrong?

- How do these alternative views of the republic’s future permeate the election of 1800? How do Adams and Jefferson use the press to articulate their visions? How does each side attempt to manipulate the presidential selection process?

RESEARCH ACTIVITY

Popular Democracy and Antebellum Party Politics

Two decades after the “Revolution of 1800,” the democratic impulse grew and the trend toward party institutionalization intensified. State legislatures, especially in the North, revised suffrage requirements to allow all white men (not simply landholding white men) the right to vote, and parties also changed the Electoral College to a winner takes all competition, strengthening the state party system. Parties encouraged popular participation, using tools such as newspapers, political cartoons, catchy songs, and community picnics to capture the excitement and loyalty of voters. Presidents emerged as the symbolic head of party and the controller of patronage. The nineteenth-century presidency shifted from the “republican executive” Alexander Hamilton had envisioned to the “prize” of a party game.

Andrew Jackson used the idea of popular democracy as a rallying cry in his 1824 pursuit of the presidency. When his victory of electoral and popular votes met with manipulation of the presidential nominating procedures in the House of Representatives to result in the election of John Quincy Adams, he spent the next four years building the Democratic Party, which he labeled the party of the common man. Winning the presidency four years later, Andrew Jackson brought his electoral coalition to staff the federal bureaucracy. The result was a new kind of partisan institution, what historian Richard John calls a “mass party,” which “was a self-perpetuating organization that mobilized a large and diverse electorate on a regular basis to win elections and shape public policy.” For the first time, the party “championed democracy.” 8 Andrew Jackson’s presidency transformed an electoral coalition into a political party with patronage. “To the victor belonged the spoils,” but for Jackson, “the spoils would increasingly come to refer merely to the perquisites that party leaders lavished on campaign workers. Rather than something to fight for, the spoils became, as it were, something to fight with.” 9 Not surprisingly, Jackson’s opponents, led by figures like Henry Clay, organized a similar institution to fight for and then with the spoils of winning the presidency. From 1840–1860, party politics dominated American political culture and shaped citizens’ perceptions of the presidency.

Have students research campaigns during the antebellum era and discuss ways in which the presidency is constructed as a symbol of the parties.

Divide students into 6 groups and have each group research a specific election through the website http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/message.

By exploring the campaign histories, candidates, party platforms, and popular music of each campaign, students can gather information about the party goals and juxtapose it with the image of the president constructed during the campaign to promote specific partisan platforms. After answering the research questions below, have students design a political cartoon about the presidential candidates that encapsulates the popular imagery from the music and the message of each party’s platform.

Research Questions:

- Who are the presidential candidates?

- What party do the candidates represent?

- What are the important issues to the party?

- How is the image of the president constructed to promote the party’s message though music and political cartoons? What characteristics are emphasized? What aspects of the presidential candidate are overlooked?

- 1840 Election: Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren vs. Whig candidate William Henry Harrison

- 1844 Election: Democratic candidate James K. Polk vs. Whig candidate Henry Clay

- 1848 Election: Democratic candidate Lewis Cass vs. Free Soil candidate Martin Van Buren vs. Whig candidate Zachary Taylor

- 1852 Election: Democratic candidate Franklin Pierce vs. Free Soil candidate John P. Hale vs. Whig candidate Winfield Scott

- 1856 Election: Democratic candidate James Buchanan vs. Whig candidate Millard Fillmore vs. Republican candidate John C. Frémont

- 1860 Election: Northern Democratic candidate Stephen Douglas vs. Southern Democratic candidate John C. Breckinridge vs. Constitutional Union Party candidate John Bell vs. Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln

Footnotes

- ↑ Alexander Hamilton, “The Federalist #70: The Executive Department Further Considered.” March 15, 1788, http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/federalist-no-70/.

- ↑ Lewis Gould, The Modern American Presidency, 2nd ed. (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2009), 2.

- ↑ Gould, 3.

- ↑ Gil Troy, See How They Ran: The Changing Role of the Presidential Candidate. (New York: Free Press, 1991).

- ↑ Jeffrey L. Pasley, “The Devolution of 1800: Jefferson’s Election and the Birth of American Government,” in America at the Ballot Box: Elections and Political History, ed. Gareth Davies and Julian E. Zelizer, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015). For more on the personal attacks between the two, see Joanne Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.) For more on the political history in the early republic, see Jeffry L. Pasley, Andrew W. Robertson, and David Waldstreicher, Beyond the Founders: New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

- ↑ Richard McCormick, The Presidential Game: The Origins of American Presidential Politics. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982).

- ↑ Joanne B. Freeman, “Explaining the Unexplainable: The Cultural Context of the Sedition Act,” in The Democratic Experiment: New Directions in American Political History, ed. Meg Jacobs, William J. Novak, and Julian E. Zelizer. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 20.

- ↑ Richard R. John, “Affairs of Office: The Executive Departments, the Election of 1828, and the Making of the Democratic Party,” in The Democratic Experiment: New Directions in American Political History, ed. Meg Jacobs, William J. Novak, and Julian E. Zelizer. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 51.

- ↑ John, “Affairs of Office,” 65.