The Presidency and Social Movements

On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy called the nation to confront a “moral crisis”—the pervasive, systematic, and oppressive discrimination of African Americans across the country.

“President Kennedy Civil Rights Address”

Read text of the speech.

For the first time in his administration, Kennedy presented a comprehensive civil rights bill as a legislative priority and a moral responsibility. Less than six months later, following the national tragedy of Kennedy’s assassination, his successor, Lyndon Johnson, urged the country to honor the legacy of Kennedy’s death with its immediate passage.

Congress passed the historic Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, and yet local barriers preventing African American voting registration remained. Civil rights demonstrations continued, and after Alabama state troopers attacked demonstrators a year later, Lyndon Johnson powerfully invoked the movement’s slogan “We Shall Overcome” to push Congress to pass a comprehensive voting rights bill.

As these famous speeches demonstrate, both Kennedy and Johnson came to support the civil rights movement with rhetoric and legislation during their presidencies. Their administrations marked a dramatic shift in tone and action from their predecessors, who had been notably timid on issues of racial discrimination. But these famous speeches were the culmination of decades of organizing by civil rights activists, years of violent—and at times deadly—confrontations between African Americans and segregationists, and months of politicking between the president, members of Congress, and grassroots activists. From the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954, which declared segregation unconstitutional to the historic legislation that Lyndon Johnson signed with the 1964 Civil Rights Bill and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, presidents had to navigate their constitutional responsibility to “execute” the law of the land with party constraints, shifting public opinion, and, most powerfully, effectively organized grassroots organizations pushing the federal government to act, or to not act.

Scholars have noted the extreme differences between Presidents Kennedy and Johnson in legislative strategy and rhetorical approaches in regards to civil rights.1 As Democratic presidents, they both worried that taking action on civil rights would cost them the political support of southern segregationists who ruled the Solid South wing of the party since the end of the Reconstruction era. Historians have argued that Kennedy dragged his feet on civil rights, preferring to focus on international affairs rather than domestic policies. 2 The public stand he took on June 11, 1963, happened only after the effective and public grassroots movement brought international attention to the violence and undemocratic reality of segregation and forced him to take a stand. Media images of racial violence at home contradicted his international promise to promote democracy and freedom abroad in the Cold War. The pressure and publicity came from below by a well-organized, dedicated, persistent and massive movement, pushing a president, who—for pragmatic, personal, or ideological reasons—was hesitant to pursue the issue.

By contrast, Lyndon Johnson aggressively and effectively pursued a comprehensive civil rights bill, making it the cornerstone of his Great Society agenda.3 He used the grief of the country following Kennedy’s assassination to propel legislation through a reluctant Congress. Though Kennedy looms large in popular memory as a “champion” of civil rights and Cold War liberalism more broadly, the “Kennedy of the imagination” was a rhetorical tool used by both the new president and movement leaders to call the country to act decisively in the slain president’s memory. As historian Derek C. Catsam argues, though the Texan vice-president had a contentious relationship with President Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Johnson was “wily enough to invoke the slain president to help pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”4

This section encourage students to think about the ideology of post-WWII liberalism—its promises and contradictions—and how presidents responded to the mounting pressures to take action to make the rhetoric of democracy and equality a reality for all Americans.

Liberalism and the Presidency

John F. Kennedy campaigned as a “proud liberal” committed to bold action. He promised to use the federal government to solve social problems and combat communism abroad.5 Lyndon Johnson, likewise, celebrated his liberalism, working to finish and expand the New Deal reforms of Franklin Roosevelt, whom he deeply admired. Though both invoked the legacy of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, the meaning of “liberalism” went through what historian Bruce Schulman calls a “profound metamorphosis” during the 1950s as the Cold War environment forced New Dealers like Lyndon Johnson to drift “right to save their political skins.” 6 As Schulman explains, when “liberalism re-emerged in the 1960s, it was a vastly changed creature—in outlook, style, and personnel.” Moreover, those discontented with the failures of liberal leaders to deliver on their promises began to mobilize, pushing the Johnson administration to voice what political scientist Sidney Milkis calls a “new version of liberalism” which encouraged more “creative intervention of the state which would address the underlying causes of social and political discontent: alienation, powerlessness, and the decline of community.”7

Tracing the shifting meaning of “liberalism” during the post-WWII period, this section provides students a window into the contested definition of the federal government’s role in social, economic, and international affairs that permeated the era, which saw the dramatic growth of the presidency at home and abroad.

SECONDARY SOURCES:

- Alan Brinkley, “Legacies of World War II,” in Liberalism and Its Discontents, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998), 94–110. Available online through ACLS Humanities E-Book Program.

- N. D. B. Connolly, “Black Appointees, Political Legitimacy, and the American Presidency,” in Recapturing the Oval Office: New Historical Approaches to the American Presidency. Ed. Brian Balogh and Bruce Schulman, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), 123-142.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Promoting a Liberal Agenda

- President Harry Truman’s Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union, January 5, 1949.

- Senator John F. Kennedy, “The New Frontier” Acceptance Speech at the Democratic National Convention, July 15, 1960.

- President Lyndon Johnson’s “Remarks at the University of Michigan,” May 22, 1964.

- President Lyndon Johnson’s Commencement Address at Howard University: “To Fulfill These Rights,” June 4, 1965.

Critiquing the Liberal Agenda

- Port Huron Statement of the Students for a Democratic Society, 1962.

- Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party Platform, 1964.

- “To Determine the Destiny of Our Black Community”: The Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Platform and Program, October, 1966.

- “Love Me, I’m a Liberal,” satirical protest song by Phil Ochs, 1966.

- “Burn, Baby, Burn,” a song by Jimmy Collier and Rev. F. D. Kirkpatrick about the frustrated pursuit of economic empowerment for African Americans.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- How have presidential definitions of liberalism transformed since Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal era? How does the liberal agenda evolve during WWII and the Cold War?

- Are changing definitions of liberalism coming from the presidents themselves, appointees within their administrations, or activists at the grassroots level?

- How do Kennedy and Johnson articulate their role in bringing economic and social change? What role do they ascribe to the federal government and its place in individual lives and the economy?

- What criticism emerges about the limits or failures of liberalism? How has the president failed, in the eyes of critics? What solutions do these critics propose?

Legislating Civil Rights: JFK v. LBJ

As Brian Balogh and Bruce Schulman note, “the fate of presidencies often hinged on how well or poorly the president managed his relationship to social movements.”8 Social movements—from the populist campaign of the 1890s to labor mobilization during the 1930s to the civil rights movement of the 1960s—“proved to be powerful forces that brought millions of passionate citizens into electoral politics and bolstered presidents’ claims to speak for the entire nation.” This was especially the case as Kennedy and Johnson grappled with the grassroots mobilization of the civil rights movement to put public and private pressure on the two administrations to push legislation through Congress. Historians have examined the legislative skills of John F. Kennedy, who served in the House of Representatives and later in the Senate without distinction, versus Lyndon Johnson, who became the Senate majority leader and truly mastered the inner workings and personalities of the Senate. While President Kennedy faced legislative obstacles that frustrated his abilities to pass legislation, Lyndon Johnson became a “Legislator-in-Chief,” beginning with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The White House recording system, begun under Franklin Roosevelt and expanded during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, provides insight into how each administration grappled with the pressing, and increasingly public, issue of systematic discrimination in federal, state, and local policies and the disenfranchisement of citizens based on race. 9 As students listen to the White House tapes below, have them examine how Kennedy and Johnson approached the legislative process related to civil rights policies.

SECONDARY SOURCE

- Sidney M. Milkis, “Lyndon Johnson, the Great Society, and the ‘Twilight’ of the Modern Presidency,” in The Great Society and the High Tide of Liberalism, ed. Sidney M. Milkis and Jerome M. Mileur, (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 1–49.

PRIMARY SOURCE: THE TAPES

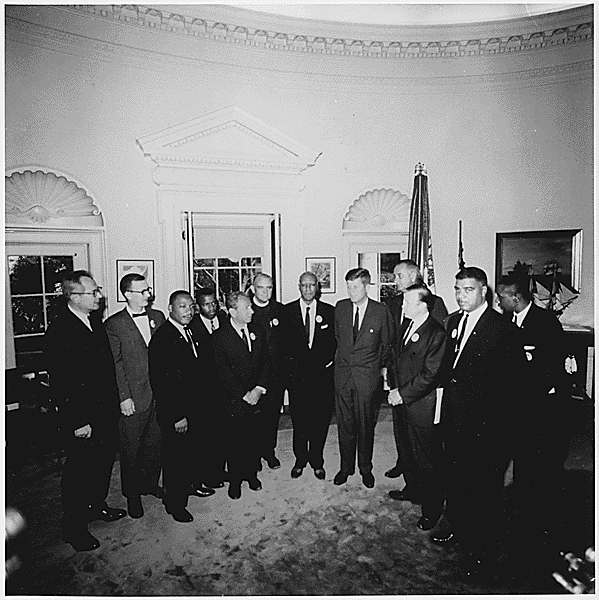

- President Kennedy meets with civil rights leaders following the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.

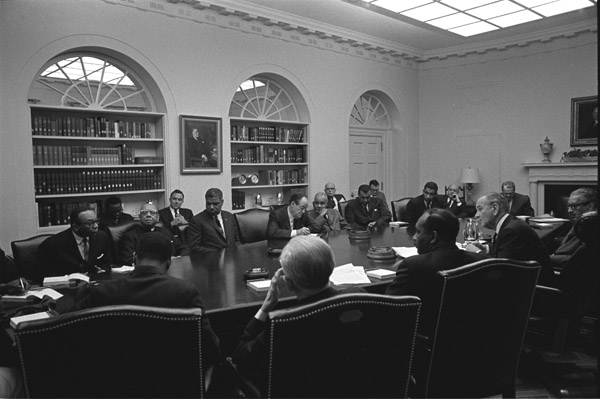

- Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr. on August 20, 1965 following the Watts riots.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What tactics did civil rights movement leaders use to pressure presidential action?

- How did Kennedy and Johnson foster relationships with movement leaders? What tactics did they use when being pressured to take action?

- How influential were the different presidential administrations in ushering in change?

- How did John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson respond to the grassroots pressures for civil rights legislation? How did they foster relationships with movement leaders?

- What does this illuminate about the president and the policymaking process more broadly?

RESEARCH ACTIVITY

Both Kennedy and Johnson faced a range of domestic crises as the civil rights movement confronted the legal, economic, political, and social system of racial segregation and discrimination.10 The presidential recording system offers insight into how they responded to organized marches, demonstration, acts of violence by segregationists, and urban riots. In small groups, have students investigate one of the crises below and research the presidential response to it.

As they research the different presidential responses, consider the following questions.

- How did the president learn of the crisis? To whom did he turn for advice?

- What concerns did the president have about using the federal government to act?

- How did the president come to his final decision to act or not to act in response to the crisis?

- Group 1: September 1962, and James Meredith’s integration of University of Mississippi

- Group 2: Birmingham demonstrations, April 1963.

- Group 3: March on Washington, August 1963.

- Group 4: Bombs in Birmingham, September 1963.

- Group 5: Selma March, March 1965.

- Group 6: Watts Riots, August 1965.

Civil Rights and the Presidency on the Silver Screen

Immediately following the release of director Ava DuVernay’s 2014 film Selma, historians weighed in on how it portrayed the civil rights movement’s leaders, participants, strategies, obstacles, and achievements, as well as the relationship between the movement and President Johnson.

- Joseph Califano, “The Movie ‘Selma’ Has a Glaring Flaw,” The Washington Post, December 26, 2014.

- David Kaiser, “Why You Should Care That Selma Gets LBJ Wrong,” Time, January 9, 2015.

- Amy Davidson, “Why ‘Selma’ is More Than Fair to L.B.J.,” The New Yorker, January 22, 2015.

Examine the Selma incident through the presidential recordings, and then watch the movie Selma. Does the movie give LBJ a “fair” treatment? Does it need to? Is there a difference between “the truth” and the “facts”? How would you present the history of Selma on the silver screen?

Footnotes

- ↑ The literature on Kennedy, Johnson, and civil rights is extensive. Recent historiographic essays provide a helpful introduction to ways in which scholars have examined Kennedy and Johnson’s impact on advancing the civil rights agenda. For an overview of the historiography on civil rights and the Kennedy administration, see Derek C. Catsam, “Civil Rights” in A Companion to John F. Kennedy, First Edition. Ed. Marc J. Selverstone, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2014). For an overview of the historiography on civil rights and the Johnson administration, see Kent B. Germany, “African-American Civil Rights,” in A Companion to Lyndon B. Johnson, ed. Mitchell B. Lerner, (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.)

- ↑ Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

- ↑ Bruce Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism: A Brief Biography with Documents. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin, 2007).

- ↑ Derek C. Catsam, “Civil Rights” in A Companion to John F. Kennedy, First Edition. Ed. Marc J. Selverstone, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 544.

- ↑ Lily Geismer, “Kennedy and the Liberal Consensus” in A Companion to John F. Kennedy, First Edition. Ed. Marc J. Selverstone, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), 501.

- ↑ Bruce Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism: A Brief Biography with Documents. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin, 2007), 36.

- ↑ Sidney M. Milkis, “Lyndon Johnson, the Great Society, and the ‘Twilight’ of the Modern Presidency,” in The Great Society and the High Tide of Liberalism. Ed. Sidney M. Milkis and Jerome M. Mileur, (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005). For an examination of the growth and “unraveling” of postwar liberalism, see Allan Matusow, The Unraveling of American Liberalism: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s. For an overview of the shifting historiography of liberalism, see Geismer, “Kennedy and the Liberal Consensus,” in A Companion to John F. Kennedy, ed. Marc J. Selverstone, 501; and Schulman, Lyndon B. Johnson and American Liberalism, 38–43.

- ↑ Recapturing the Oval Office: New Historical Approaches to the American Presidency, ed. Brian Balogh and Bruce Schulman, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), 69.

- ↑ Jonathan Rosenberg and Zachary Karabell, Kennedy, Johnson, and the Quest for Justice: The Civil Rights Tapes. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003).

- ↑ For a transcription and analysis of these crises as seen through the tapes, see: Jonathan Rosenberg and Zachary Karabell, Kennedy, Johnson, and the Quest for Justice.