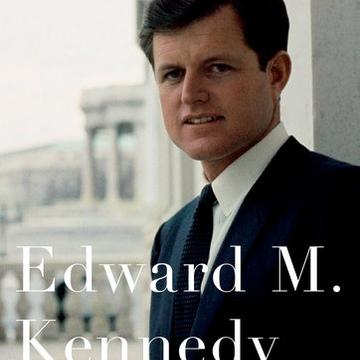

From hawk to dove

Kennedy supported the Vietnam War. Until he didn't.

[Excerpted from chapter 6 of Edward M. Kennedy: An Oral History, by Barbara Perry]

Like many Americans, Senator Edward Kennedy initially did not oppose the war in Vietnam. He supported President Kennedy’s policies to increase the flow of aid and military advisors to the region. Following his brother’s lead, and the consensus among both Democrats and Republicans during the Cold War, the senator believed it was necessary to take a strong stand against communism’s spread. He continued to support such policies when Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency upon JFK’s assassination. Senator Kennedy agreed with the 1964 Tonkin Gulf resolution, which escalated America’s role in the conflict. (Recovering from his near fatal plane crash that summer, however, he was not present to cast a vote on the measure. Yet in a recorded phone conversation, Kennedy told LBJ that he supported the resolution.)

In 1966, he wrote his first critical statement on Vietnam, marking the beginning of his transition from hawk to dove. One of Kennedy’s main concerns regarding Vietnam dealt with the war’s impact on the American people.

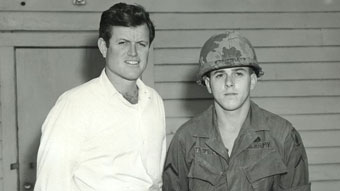

Kennedy’s opposition to the war increased after he organized his own inspection tour in January 1968, where he witnessed rampant corruption within the South Vietnamese government. He grew increasingly disillusioned with President Johnson’s reports on the war and questioned their accuracy. As Senator Robert Kennedy was moving closer to challenging President Johnson for the Democratic presidential nomination, Edward Kennedy became a national leader in the antiwar movement. Bobby’s death, in June 1968, Teddy continued their work, calling on the Johnson and then the Nixon administrations to stop the bombing campaign and to refocus the peace talks on US withdrawal from South Vietnam.

Edward M. Kennedy: I believe it was 1966 when I went to the University of Wisconsin to speak for both Gaylord Nelson—who was moving towards an antiwar position but hadn’t declared it—and Pat Lucey, who had been very involved with my brother’s [1960 presidential] campaign. We were at the University of Wisconsin. We went into this big hall, and in the back of the hall were these white sheets with skeletons drawn, dead people, all done in charcoal, graphic—almost ghoulish, but not ghoulish. There were also marks of explosions—big white sheets with black charcoal or black paint on them all across this back wall, and probably 3,000 students. ...

I was the first one to get up and speak, and there was a roar in the crowd as I started speaking. There was a lot of disturbance, disturbance, disturbance. I asked if they were going to let me speak. "No, no." Then a lot of chanting started against the war, and it just intensified. I finally said, 'I'll let one of you come up. I'll listen to you speak, and then you listen to me.' One of them finally said okay. Up comes this fellow named Schultz. I can still remember. He was from New York City, and he got up at that podium and he gave a talk and a half for about seven minutes about the war, antiwar. The place just cheered and went bananas for this fellow—emotion and feeling ran high in that place. Then he stopped, and he got the roaring, roaring, roaring approval of the students.

So I said, "You can keep going. Keep going." He mentioned a couple of other facts, and then he stopped. I said, "Keep going. This is a major issue. Keep going." And he said, "I don't have anything one to say." "You don't have anything more to say? That's all you had to say?" Then the crowd started getting mad at me for trying to keep after this guy. But he just ran flat out of gas. He went on dead empty.

So he left, and then they let me talk for the same period of time, eight minutes I think it was. I talked generally about Vietnam—I was critical. We hadn't gotten to the point of the exit strategy at that time; it was the following year. ... At the end of my talk the authorities and the police came in and took us all out. They never let them speak because they were worried about violence on the campus.

Q: What was your public position at that time, and why were they going after you?

EMK: They were going after anybody who wasn't for getting out of Vietnam and getting out then....

I think '67 was the year when a number of politicians, including my brother [Bobby] and me, made that transition. So the seeds of doubt had been planted in my mind during that time.