Transcript

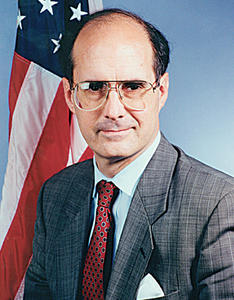

Riley

This is the Strobe Talbott follow-up interview as part of the Clinton Presidential History Project. You’re kind of a bookend for us. I think the first interview that we did in this project was the one that we did with you and Warren Christopher. We’ve done about 130 interviews in between that one and this one, and we’re hoping to get finished in the next couple of months.

So, I’m grateful for the time. I had told Katie [Short] earlier that because of the limits on time, I had preferred to focus on the biographical things that we haven’t gotten to because of the—you’ve done a lot with your earlier writings. But I wanted to stop before we got into that and ask if there were in fact some things about your experience in the administration that, for whatever reason, you hadn’t recorded in either The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy or some of your other writing. Were there things that were either not particularly relevant to the work that you were working on at the time or maybe things that were too sensitive for you to put into publication that you’d like to have the chance to talk about for the long-term historical record, realizing that we can hold on to this if it’s too delicate?

Talbott

Well, two things come to mind. You’ve set me up nicely for this, of course. I do wish we had more time because it’s mighty important. Here, I’m thinking of things that I was involved in. These are in the policy area, Haiti, and in the personal area, Monica [Lewinsky], etcetera. I’m still not totally comfortable talking about the latter, not that I have anything the world doesn’t know. And therefore, since I don’t think I have any real value added there, maybe you’ll find some interesting line of questioning that will draw me out of reticence.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

But let’s just do Haiti.

Riley

I’ll give it a try.

Talbott

You’ll give it a try. I assume you’ve read Taylor Branch’s book.

Riley

I am in the middle of it.

Talbott

Well, if you’re in the middle, then you’re not there yet. But maybe after you’ve read Taylor Branch’s book, because I did help him with that.. . .

Riley

All right. Haiti.

Talbott

I think Haiti was an important episode that I did not write about. I wrote a little bit about it in The Great Experiment: The Story of Ancient Empires, Modern States, and the Quest for a Global Nation. Have you seen that book?

Riley

It’s been awhile.

Talbott

Okay. Well, some of what I have to say I do think bears some treatment in the project for several reasons. One, it was the firstleaving Somalia and that debacle aside, because that was an inherited situationit was the first, really, use of force. A President who was not naturally inclined to hard power became convinced fairly early on that it was going to require hard power to restore democracy.

Riley

Can I put a flag by that comment,

not naturally inclined to hard power,

and let’s come back to it because I’d like to get you to elaborate on—Talbott

Yes, at any point. It was a mixed experience, to put it mildly. It succeeded in the sense that the United States was instrumental in restoring to the Presidency the first genuinely democratically elected President Haiti had ever had. It had succeeded in getting the United Nations Security Council to pass a resolution authorizing all necessary means (aka, force) to restore democracy, which had never happened before. Succeeded in getting the OAS [Organization of American States], including countries that were very skeptical about any organization going around the hemisphere whacking people to support it. And it succeeded in pulling off the regime change, restorationit was called

Operation Restore Democracy

without a single U.S. combat death. One G.I. [government issue] committed suicide as I recall, and a few Haitians died because they were stupid enough to pull guns on American soldiers.But it cannot be regarded as a great triumph because of the weakness of political culture and the deficiencies and excesses of [Jean-Bertrand] Aristide himself. And so it ended up being kind of a frustration, which Bill Clinton is living with to this day. Hadn’t it been for his most recent heart episode, he would’ve been down in Haiti last week, and as it was he sent Chelsea, and still, that’s earthquakes. But, of course, one reason that the earthquake was as devastating as it was is that it’s such a terribly governed country and it didn’t have anything like just the most basic public safety infrastructure. So, the legacy goes on.

So I would say that that is an episode you might want to draw others out on who were even more intimately involved. Sandy Berger, you can go back and talk to Sandy at some point. Tony Lake. Big time.

Riley

We talked to both of those. But you also had a piece of this.

Talbott

Oh, yes.

Riley

How did you come by a piece of the action in this case?

Talbott

I don’t know. Is my own personal story of interest for use in this?

Riley

Yes. Of course. A lot of what we are trying to do is mosaic. It’s piecing together what we can about the administration from what people say.

Talbott

Well, who doesn’t like talking about himself, at least on most subjects? It’s a simple story in a way and notfortunately nottotally understood. I, as you know, shared a house with him; got to know him at Oxford. In fact, on the boat ride over to Oxford—I’ve written about this in The Russia Hand and elsewhere. I shared a house with him for a year and stayed friends with him.

When he became President, he asked me to come over see him in the Hay-Adams Hotel. He offered me the ambassadorship to Moscow. I couldn’t do it for family reasons. I thought that was the end of it. Bob Reich, who was camping out at my wife’s and my house during the transition, said,

Well, why don’t you see if Bill will give you a job here in Washington?

I said,It never occurred to me.

He said,Well, I’m going down to Little Rock tomorrow, what if I mention it?

He did. I got a call from Warren Christopher a couple days later saying,Come on over to the State Department and coordinate Russia policy.

The Deputy Secretary of State bombed out and they were looking for a new Deputy Secretary of State. Clifton Wharton was his name, and—Riley

What was the problem?

Talbott

Well, he was terrible at the job. He just didn’t do the job very well. He seemed to be much more interested in—this is obviously—

Riley

Of course.

Talbott

He was much more interested in the prestige and representational part of it as opposed to really getting a grip on the policy.

Riley

Right.

Talbott

Christopher would have never—first of all, Clinton would have never brought me into the government when I said no thanks on Moscow if it hadn’t been for Bob Reich. And Christopher would have never brought me into the State Department if Clinton hadn’t said,

Bring in Strobe and have him do Russia.

But Christopher and I, in the course of that year, got to be very close and he was increasingly dissatisfied with Wharton. When he decided to fire Wharton—Tom Donilon had a lot to do with that decisionhe put Donilon, Peter Tarnoff, and me basically together as a search committee. And we came up with a number of people and actually, with me as the intermediary in a couple of cases, offered the job to Morton Abramowitz; I think Mike Armacost, who as coincidence would have it, proceeded me in this job here at Brookings; and I don’t know if we actually offered it to Steve Bosworth. We certainly considered Steve Bosworth. We considered Winston Lord. A couple of people said no, a couple of people didn’t work out, and I was sort of in, not quite the same way, in the Dick Cheney position.

Well, why don’t you do it, Strobe?

So that’s how I got to be deputy secretary. And one of the reasons is because during the course of that whole period, the issue of using force—or hard power—was becoming more front-and-center. Obviously, we weren’t thinking about using force anywhere in the former Soviet Union, which had been my area of concentration. But I was increasingly included in conversations about other areas where force was an option—or perhaps a necessity. There were several where that was most likely: Haiti and the Balkans in the first instance, Iraq, and North Korea. I think Chris felt that I was in the right place, if I could put it that way, in the way I thought about those issues.So, when I became, or was nominated to be deputy secretary, I had a rough confirmation process. Nothing compared to what people have gone through in the past year. No, it was actually something compared to that, but as soon as I knew I was—he designated me for the job, then he brought me into planning on Haiti. So I was the seventh floor designee for dealing with Haiti.

Riley

Could you quickly take us through your account of what you were doing in your role as the decision to use military forces?

Talbott

Yes, and I have some private notes that I can go back to if there are things that are of particular interest.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

With the wonders of the search function, I can actually scroll through them and—

Riley

You could do that or, if you wish, some of these things you could append to your transcript as reference materials and we would guard them with the same degree of—

Talbott

I’d have to be real clear on the ground rules there but, yes, I can do that. I basically—keeping diaries was treacherous. In fact, that’s a whole other issue. It’s one of the important things about what you are doing. I also wrote memos to the secretary and the National Security Adviser that were personal, confidential, and eyes only, and those are the only ones. You’ll notice what that doesn’t say. And so I was able to keep those.

Riley

Presumably those are in the papers in the library.

Talbott

Yes. And Christopher has them. In fact, I think one of the interesting things about them—I trust Christopher; you’ll have to find out from Christopherthat they should include his notations back to me because they were essentially a written dialogue.

Riley

Okay. Excellent.

Talbott

A lot of it was on Haiti. Well, no, I mean it was pretty—in its own way it was simple. It was not simple to execute but the idea was, quoting George Herbert Walker Bush,

This coup will not stand.

And so, basically we gave the junta a Hobson’s choice, and unlike—a Hobson’s choice is supposed to lead to only one conclusion, and they did the wrong thing. They forced us to come in. They didn’t leave voluntarily so we had to go in and throw them out. But the key part of it was dealing with an extremely skeptical Congress that was also somewhat polarized on the issue—the Black Caucus and the Florida delegation wanted to get the thing solved because of the refugee problem, and the other was the international diplomacy. So I was involved in both of those, and then the third was what to do with the refugees themselves.John Deutch, who might be worth talking to at some point—

Riley

We did.

Talbott

—he was the Secretary of Defense at the time. He spent a lot of time bouncing around the Caribbean looking for countries that would take batches or scores or hundreds of refugees. But then we had to have a timeline. We had to have a deadline. We had to deal with the Gang of Three, Sam Nunn, Colin Powell, and Andy Carter—

Riley

Said with eyes rolling, by the way.

Talbott

Said with eyes rolling—who, every time he got involved in one of these episodesand he did in Haiti, he did it with [Slobodan] Milosevic, and of course he did it with Kim Il-Sungwas not helpful. Made it hard to make the hard and right choice, one for the individual we were dealing with—

Riley

With Haiti was there a—I’m trying to recall, he requested permission to do this? Or was Carter drafted in this case?

Talbott

Oh, I don’t think he was drafted.

Riley

He didn’t have a piece of that.

Talbott

No, that doesn’t sound right. I could be wrong about that—you mean, like it was our idea to [inaudible].

Riley

Yes, I’m trying to recall whose idea it was that the Gang of Three would go down there.

Talbott

It feels like it was Carter’s.

Riley

In any event, if you don’t know that—

Talbott

Yes, you could almost Google the answer to that.

Riley

Exactly, somebody will turn up with it.

Talbott

I just don’t remember. It doesn’t feel like something we would have suggested. Partly because we wouldn’t have had a high degree of confidence that they’d deliver the message that we would want delivered, with Carter in particular.

Riley

Let me shift gears and ask you. Aristide was a controversial character, even within your own government.

Talbott

You bet. And particularly in the eyes of the Director of Central Intelligence, Jim Woolsey, who was convinced, not without reason, that he was a bad actor, and the Vice President was very concerned. I can remember Leon FuerthI assume somebody you’re talking to?

Riley

Yes.

Talbott

I can remember [Al] Gore having a white board with colored magic markers and doing a schematic decision tree. If we can determine that he has this connection with this cartel and this much bad stuff, drugs were coming to—that leads you to this decision. That lost me very early on. It was like his approach to climate change, you understand a little better. But it was incredibly Goresque and disciplined and rational almost to the point of being very rational, more rational than the world, let’s put it that way. So he was deeply into that. Then, of course, in the end it developed that we had to do it.

But that led to a very fateful decision, which was whether to allow, as it wereand that was the right verbAristide to then run for another term because it depended on whether you counted against his constitutional term the time he had been in exile in Florida, or if you allowed him to start the clock over again. We decided, partly because of principle, largely because of principle, but also because of our discomfiture with Aristide, that we should insist upon him staying with what would have been the original constitutional term, and that required him to step down and handpick [René] Préval, and all that.

Then, to this day, I think among those of us involved, there’s either—in my case, ambivalence or uncertainty, and maybe in Tony’s case; I wouldn't want to speak for him, but you should ask hima feeling that we made a mistake and we should have let Aristide run for a second term; he would have been more effectual. I think effectual and Aristide don’t belong in the same sentence, so I’m skeptical about it.

Riley

Were there consequence of that? You mentioned the—

Talbott

It’s hard to know, Russell, what the causality is here. I mean, Haiti is so screwed up and so endemically, systemically, and historically screwed up, that there’s a temptation to let that become an excuse for whatever misfeasance and malfeasance there is. But I don’t—Haiti has been so unlucky in so many ways, including in the fact that this particular individual, Aristide, became the populist leader that he did and was the first elected President, philosopher-king not, philosopher-priest not.

Riley

Okay, the predicate for getting into this, or one of the predicates, was that President Clinton was not somebody who was inclined to use hard power, but in this case found that it was necessary. Talk a little bit about your perceptions of Clinton as somebody who was not inclined to use hard power. I wonder if you could elaborate a little bit more on the process of his coming to grips with the idea that as President—

Talbott

Which he did.

Riley

—he had to do this.

Talbott

Well, there’s a danger both of spending too much time on things already on the record. There’s also a danger of pop psychology, but the hell with it.

Riley

I’m less concerned about the latter than I am the former.

Talbott

You mean?

Riley

Because we’re short on time.

Talbott

Then I’ll do it telegraphically. Vietnam. Anybody for whom a formative experience in his life, as it was for me, was going to have a little bit more of a default reluctance to have the United States going in and kicking down doors around the world. Second, Clinton is a conciliator, that’s his thing. It’s the Rodney King doctrine and he’s very good at it. Never better, of course, than in the Middle East. It was just one of the great sadnesses of the Presidency that he didn’t quite get that one over the line. But that was where he was comfortable, felt he was at his best. But, to his immense credit, when it came to needing to pull the trigger he would pull the trigger. He did on Haiti and he did on the Balkans, and getting him there—which I think is part of what you're asking about—

Riley

Right.

Talbott

—involved a great deal of dialectics. But they were genuine dialectics. One of Clinton’s—I think we may have touched on this in the first interviewone of Clinton’s both maddening and admirable, and I think ultimately productive characteristics, was the relish he took in impersonating his own critics and saying,

Well, what about when they say—?

Then he would do a better job of slashing and burning his own policy than anybody in the press mercifully was doing. We’d have to sit there and say,Mr. President, this is

your

policy.

He’d say,Yes, I know, but what about when they come at me and say bah, bah, bah? What about if this happens?

It forced us to say,Yes, we need an answer to that.

Or,We need a plan B if plan A doesn’t work, or plan C if plan B doesn’t work.

And so forth and so on. It was exasperating at the time and it was time-consuming, but he always had enough time, it seemed, and we got to the right place.Riley

Who were the key people in helping him move in this direction? Do you feel that your own role was important in pressing him this way? I mean, you’re somebody who might also have come from the same position he did.

Talbott

I was, yes, that’s a fair question, particularly given the fact—no, I was a little bit more of a hard power guy. Tony was passionate on the subject. Chris was very uneasy with it, but he knew that we were on a—Larry Pezzulo had had the brief before I did. He knew that we weren’t getting anywhere on that course. So Chris was basically—I wouldn’t say deferred to me, that would be condescending to him, which I don’t mean, but he trusted my instincts.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

Let’s see, was it [Les] Aspin or was it [William] Perry already? Yes, Perry and [John] Shalikashvili were very important, and they were,

We’ll do it, sir, but we’ve got to be very careful about this kind of thing.

It was kind of classic. I don’t mean that as a putdown. And Deutch had his reservations about this and he was quite influential, particularly with Perry. Who else? I’m trying to remember if Mack [McLarty] or [Leon] Panetta—I don’t think they were in on this particularly.Riley

You’re focused principally on Haiti, the decision to use force?

Talbott

The decision to use force. I’m trying to remember, do you recall when Woolsey quit?

Riley

It was about a year—

Talbott

Well, see, we didn’t go in until—was it ’94?

Riley

Right.

Talbott

Long story, but Clinton had no use for Woolsey. Woolsey got into the DCI (Director of the Central Intelligence Agency) position—I remember this one because it was a decision made around the time of the Renaissance weekend in ’92, so January ’92. They wanted a neocon [neoconservative] for ticket balancing and they were going after, what was his name? Not Dave McGiffords but—

Riley

[Dave] McCurdy.

Talbott

McCurdy, thank you. I forget why he didn’t work.

Riley

I think he wanted State or Defense. I think he was shooting higher, if I remember correctly.

Talbott

I thought they were considering him for Defense. In any event, they looked at a couple of people who were sort of neocons and they ended up with the worst imaginable, for a variety of reasons. But Jim has his strengths and he certainly is dogged. He would have made a very good prosecutor. He got into a prosecutorial mode more than an intelligence analysis basically, and Clinton just basically shut him out.

Riley

On this same point, and then we’ll move on. His, Clinton’s, relationship with the military was problematic from very early on but you’re describing a President who becomes more acclimated to hard power over the first year or so. I don’t really know how to frame a question on that, I’m just throwing it out as an observation to see whether the extent to which the Pentagon types—I mean, Colin Powell must not have played a very crucial role in bringing Clinton along on this. If anything, the military seemed to be reluctant on occasions to get engaged.

Talbott

Yes, you’re on to something because, in fact, Clinton was in trouble with the military, both on the hard end and on the soft end. It was gays in the military, and need I say more? The fact that he was a draft resistor, need I say more? So he doesn’t like what we do for a living. Or he doesn’t understand our culture, whatever. Then all of a sudden he’s saying suit up and pack your kits and report to Fort Bragg.

Then they say,

We don’t do police operations. We don’t kick down doors, we do serious geopolitics.

So you might want to talk to Wes Clark. I don’t think Wes’ appointment, first as Sync South, Southcom, the Southern Command, and then as SACEUR (Supreme Allied Commander Europe), burnished Clinton’s credentials with the military because Wes wasn’t very highly regarded, for good reason. Shali, Shalikashvili: fabulous. Unfortunately, he’s not in a condition to be interviewed.Riley

A colleague of mine interviewed him a couple of years ago and basically confirmed it didn’t work very well.

Talbott

As I said, it’s a tragedy. You know he had almost the same, almost but not quite the same, stroke that Bill Perry had. Bill Perry is highly functional and exercising and running around, giving speeches, and Shali is in terrible shape.

Riley

But it is important to know that he’s crucial to this.

Talbott

Shali was—you ought to spend some time with people who know better than I how Clinton came to the decision to have Shali succeed Colin, because there was an admiral who was also very much in the running and who would not have been good, and Shali was the best. If we get around to Partnership for Peace and NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) enlargement, Shali was crucial there. He was crucial on the Balkans.

Riley

That’s helpful to know. Let me go to the other piece of this that you said that you didn’t deal with and that you’re still hesitant to talk about, and that’s Lewinsky at the far end. Again, I may struggle to bring questions here, but your account in the book, in The Russia Hand, is basically that you’re very far removed from President Clinton at that point in terms of being immersed in your own activities.

Talbott

I don’t think that’s quite—

Riley

Maybe I’m not reading that—

Talbott

It’s not the way I’d put it.

Riley

Let me throw that out.

Talbott

Far removed from his sex life, but that’s not being far removed from the President. I expressed it as well as I could in the book. The issue had been out there either as buzz or louder than buzz for a very long time, and I had always been both upset by it and mystified by it. It didn’t connect with my sense of the individual from having been a 22- and 23-year-old with him as young bachelors in Oxford, England, in the ’60s for God’s sake. This was not a monkish existence. There were plenty of my contemporaries who were, even by those standards, libertine. Bill Clinton just wasn’t one of them. So it never quite came together. I never understood the phenomenon, but there was obviously a phenomenon.

Riley

Got it. I guess the piece of this that I’d like to ask you directly about is, were you somebody who Bill Clinton looked to in the aftermath of this to try and come to grips with the political fallout and so forth?

Talbott

Not at all. I think that the people—one of the points I was going to make earlier is that my degree of intimacy with Clinton was very much exaggerated. That said, I did not waste time trying to correct people for obvious reasons. The more people assumed I had the ear of the President, the more power I had. So fine. But it actually relates in a way to the issue that I’m not evading, or maybe I will evade a little bit. But Clinton had this, has this, extraordinary ability to make anybody, either on an individual basis, small group, or a thousand people in the room, feel that he is connecting with them personally. Maybe [Franklin D.] Roosevelt had it, I don’t know. I doubt we’ve ever had a President who was that skillful at this thing.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

Also, he has this capacious memory and somebody’s name comes up and he’ll make some comment like, oh, yes, he’s a great friend of mine, and so forth. So you put that all that together with the fact that he loved his youth, he loved being a Rhodes scholar, and he felt a particular bond with all of us who were part of that coterie, that band of brothers. So you put all that together, and the way he’d kind of give me a hug and tease me about my lack of taste in clothes. I remember him introducing me to Boris Yeltsin the first time saying,

Here’s my friend Strobe. His socks didn’t match until he was 40 years old,

or something like that. Things like that would make people think, Wow, these two are really, REALLY close. Because I went back to Oxford with Clinton and shared a house with him, I ended up in a lot of people’s minds in the same category as, say, Mack McLarty. That was, as I say, an exaggeration.Now, on the sex stuff, there’s probably nobody who was really in the inner circle there except when it came to technical, legal question maybe Greg Craig:

How are we going to defend ourselves on this?

And Joe Lockhart,What are you going to say when you go out to the press?

—things like that.Riley

Sure. So there’s not any more of a story there of your relationship with the President.

Talbott

Not of mine. It was a no-go zone—for both of us. What I have to say on the subject is in Taylor Branch’s book.

Riley

Okay, I just wanted to make sure I wasn’t missing anything.

Talbott

There were a couple of times when I would be seeing him on other business, and there are two things, two kind of contradictory memories. One is that I would know that all hell was breaking loose. One account I was thinking about with Russia, coming in to decide whether we were going to bomb the alleged illicit pharmaceutical factory in Sudan like two days after—the morning after the Monday night speech. He was totally focused and only wanted to talk about that, where everybody else in the room was ready to blow their brains out, or blow his brains out. So he had this ability to compartmentalize.

But I also was with him a couple of times when he just exploded at his congressional opponents, at the press, for going after him on things. But he wasn’t exploding in a wayhe says, talk me through this, Strobe; how should we deal with this?it was just vent. I would sit there and go, hope this ends soon.

Riley

But you had seen this before? I mean, I’ve gotten accounts from others that his anger was very much—he was very mercurial.

Talbott

Yes, he didn’t blow up at me too much. One of his thingsactually, you’ll come across in Taylor’s bookis that Hillary was very mad at me for recommending Bobby Inman for the Secretary of Defense job, and I think with good reason. Anyway, talk about weird sex. How could we have known? But in any event, Clinton was very forgiving about it. And he was forgiving on something—it will come to me. He never blew up at me. I saw him blow up at Sandy a couple of times, but that was partly because Sandy had a—this was more when Sandy was National Security Advisor than when he was deputy, was in the position of having to make him eat spinach, as we put it. He’d say,

You’ve got to stop now, you have to do this.

God damn it, I’m the President. I’m tired of you people pushing me around, and you in particular.

But I can remember him blowing up in India at Sandy once, and Sandy was really—I mean, having the President ream you out in front of a bunch of people is not pleasant.Riley

Yes.

Talbott

Within an hour there was a big hug and I’m sorry. So, but I’m off topic.

Riley

No, there’s no topic.

Talbott

There was not any time where he, as it were, let down his hair with me about what was going on. Going back even to ’88, there was speculation, that was when Gore ran for the nomination—

Riley

He had a lot of people come to Little Rock and—

Talbott

Yes, and Clinton came to Washington. I was bureau chief at the time, I think. I was either bureau chief or columnist, but in any event I organized a dinner for him to meet with a bunch of people and he stayed at the house. There was talk about women. Not with him, but there was stuff in the air. One reason he wasn’t going to run was because there were some things out there that would come out if he were to run. My memory on this is very vague, and even if I had done all the homework you assigned me I wouldn’t be able to be any less vague.

I remember the essence of it, which was that—and my late wife was with me at the kitchen table. I tried to get him to give me some sense of how concerned he was about anything of that kind. And he shut me down. Not in a brutal way,

just fuck off on that, shut up.

Rather, he just headed in another direction. So I never got close to that.Riley

So it was not something—you were curious in ’88 about whether this was something that would prohibit him from running for President—

Talbott

Not so much curious as concerned. I really didn’t much want to know, but was worried about what might become known, if you see the difference.

Riley

Can we go back to Oxford.

Talbott

Sure.

Riley

When do you first meet this person and what do you make of him?

Talbott

I thought we’d done that.

Riley

That’s not something that we’ve talked about.

Talbott

The two stories I would tell are the following. I think Katie has maybe even heard this. There were 32 Rhodes scholars, and 31 of us took the boat together from New York. We gathered at Swarthmore College, near Philly [Philadelphia]. Had a dinner together, got on a boat, and spent six days, whatever it was. I think it was the USS—it was either the France or the United States.

Riley

It was the United States.

Talbott

I did two years in a row. I loved it so much I went back a second year on the boat. In any event, that was our first meeting. I just thought he was terrific. He liked me and we had a lot of interests in common, but he liked everybody. The line I’ve used is Rhodes scholars individually and collectively are not known for their modesty. So, if you had put to them the proposition that one member of this group would be President of the United States some day, there would have been willingness to accept that as a possibility. So that’s not unusual. But if you were to take a poll of them and say who in this group is going to be President of the United States, he would have won hands down.

Riley

No kidding.

Talbott

Absolutely. A totally unprovable proposition but I’m certain of it. You just knew that Bill Clinton was going to be a politician and that he was going to probably be President. It was part of his charm that he didn’t make a big deal of it. He didn’t say,

I’m Bill Clinton, I’m running for President.

You just knew it and you didn’t resent it. Maybe some people did. Slick Willy came along later. So that was—I think if you interview other people, there are a lot of them around, Reich in particular, who has had his own falling out with Bill, and others, John Isaacson of Isaacson, Miller, Rick Stearns, you would find that to have been the case. So, all of us just knew that he might or might not get there, but that that was his destiny.The other thing was his generosity. I had an eye injury on the squash court. I think it was in my first year, yes, because we were not yet sharing a house. He was living in University College, I was living in an annex of Magdalen College and I saved seven bucks on a pair of glasses getting nonshatterproof lenses in them in New Haven the year before. I got hit in the face with a racket. The glass went into my eye and I was in the hospital for three months or something like that with an operation.

Riley

In the UK?

Talbott

Yes, didn’t cost me a penny. Don’t complain to me about the British national health. Bill Clinton would come see me a couple of times a week and read to me because I couldn’t read. I remember in particular that he read Pax Americana, which I think may have been Ronald Steel; that’s checkable. But I know that was the book, Pax Americana, cover to cover. He would just sit there by my bedside, talk, and just—he didn’t have to do that. He didn’t think I was going to be a delegate.

What else? It goes back a little bit to what we were talking about earlier. Very social. He had a kind of a girlfriend named Sara Maitland; she turned out to be a lesbian, so I don’t know what to do with that. He was a voracious reader. I remember he read and got me to read somebody Blake, I want to say Robert Blake, biography of [Benjamin] Disraeli. He read a huge amount of British colonial and parliamentary history. He read The Magic Mountain, and Walker Percy. He was always reading.

Riley

But less focused on his program there than perhaps you were, or others?

Talbott

Yes, I don’t think—did he ever finish his degree?

Riley

No.

Talbott

I didn’t think so.

Riley

There was at some point—

Talbott

I think he was doing PP and E, Politics, Philosophy and Economics. But I was neverhe wasn’t a grind. I was grinding away on a dissertation about Russian literature. He was just taking it all in. There was a guy named Bob Earl, who you might want to talk to, an ex-Marine guy who actually got caught up in Iran-Contra or something. I remember going into London, to the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, Royal Opera, seeing ballet and opera and things like that. He just was taking it all in. Of course, and then marching on the U.S. embassy.

Riley

Yes, he was marching?

Talbott

Oh, yes.

Riley

When this becomes a live issue during the campaign later, were there misinterpretations of what—

Talbott

There I would refer you to the record. I was writing a column for Time, and my deal with the editors of Time was that I was going to recuse myself from writing anything whatsoever about Bill Clinton. If that was awkward, we’d just have to live with it; somebody else would have to write it. I made one exception to that, which is when the draft stuff came out because I knew the draft story firsthand. I’d lived it with him. I wrote a two-page special article in Time. So everything that I knew is there.

Riley

Okay, we can do that.

Talbott

We can find that for you.

Riley

Let me ask you, because I’ve read David Maraniss’ account a couple of times.

Talbott

Fabulous book.

Riley

I thought so as well, but because I wasn’t there I didn’t know whether it resonated—

Talbott

Totally.

Riley

—as truth, from your perspective.

Talbott

Well, I thought Clinton was really dumb not to speak to him, and I blame it largely on [George] Stephanopoulos. But in any event, it would have been a better book, and a better book for Clinton, if Clinton had talked to him.

Riley

Maybe so, but I still think it’s almost unmatched in terms of a biography, pre-Presidential biography done, especially while somebody is in office.

Talbott

Not only while he was in office, it came out within his first year.

Riley

Some point in ’95, maybe ’96.

Talbott

I thought it was earlier.

Riley

Is there any other piece of the Oxford story? You got to know him fairly well. He comes back while you’re still—

Talbott

That’s how we ended up in this house together. The way that worked is he thinks he’s going to be drafted. He goes home. He makes no arrangements on a place to live through the second year. He’s not drafted. He comes back and Rick Stearns, who is a federal judge up in Boston, says come on in, live in my digs. Rick Stearns meets a young lady and says I’d really rather have her live in my digs. So Clinton is out on the street. Frank Aller, the name you know, and I had this house up in north Oxford and we had him move in with us.

Riley

Was he a good roommate?

Talbott

He was a fabulous housemate. I always say housemate. Nobody who wasn’t married to me would want to be my roommate, maybe even there.

Riley

A good housemate.

Talbott

A great housemate. He tells the story, which I think is true, of getting up early and making me scrambled eggs when I was working on the [Nikita] Khrushchev memoirs, great.

Riley

So you come back from Oxford, and you have occasional associations with Clinton when you come back?

Talbott

We stayed in very close touch. My wife, she wasn’t my wife yet, but she and I went to visit him at Yale Law SchoolI can probably figure out when—so we’re talking, it was probably in ’71, before I finished at Oxford. That’s where we first met Hillary. Hillary and Bill were in a moot court together, and what I can’t for the life of me remember, but one of them certainly will, is whether they were on the same team or opposing each other. It was clear that there were good things going on.

Riley

You had seen him with companions at Oxford, was there anything different about Hillary?

Talbott

Female companions?

Riley

Yes, female.

Talbott

You know, that goes back to the mystery of it all. He didn’t have—I mean, I had a serious girlfriend I was determined to marry who was 6,000, 7,000, 8,000 miles away.

Riley

This was your future wife.

Talbott

My wife. So I was kind of an objective observer.

Riley

Well, God bless you.

Talbott

The anthropology going on around me. Bill was incredibly social, had girls around but I never had the sense that he had a serious girlfriend in Oxford. Now, I’ve read since, I can’t even remember whoSara Maitland is the one that I remember; she was a poet—had to go into a psychiatric hospital for a while, and he was terrific about going out, like with me in the hospital, checking up on her. But no, there was nobody that I would have said, they’re a couple.

Riley

You went to Little Rock at some point?

Talbott

I went to Little Rock?

Riley

Hot Springs?

Talbott

Was it Hope? No, I didn’t go to Hope, I went to Little Rock.

Riley

To Arkansas, I’ll put it that way.

Talbott

Yes, it was when he was either getting ready to run for, or was running for John Paul Hammerschmidt’s House seat, that would date it. There was another guy named Jim Guy Tucker, who was subsequently Governor, who was around. I drove around the state with him and went to see his father’s grave, got to know his mom and Jeff [Dwire], his stepfather at the time, and brother Roger [Clinton].

Riley

Do you have any specific recollections? Was that your first trip to the South?

Talbott

No, but I don’t think I’d ever been in Arkansas. I remember going to Fort Smith with him. He was watching the campaign basically. I’m not sure he had formally declared or was just getting ready for it.

Riley

Did you ever get the sense that he felt awkward going back to Arkansas after having been out in Oxford and Yale. Was the return to Arkansas in any way confining to him?

Talbott

I got the impression of the opposite. [J. William] Fulbright was his mentor and role model. He probably could have imagined being Governor for a while and being a Senator. No, I think—how many terms did he serve, eight?

Riley

Well, they were two-year terms and then I think they changed eventually. So it would have been one term and then he was elected—

Talbott

He was the youngest Governor and then the youngest ex-Governor.

Riley

Exactly. So he had a single term before, and then I think he had been elected to the third term that he didn’t quite fill out, if I remember correctly. So you’re keeping up with him at a distance.

Talbott

But he used to come to Washington a lot with the famous troopers, and he would often stay at our house. My kids were very small at the time. You can figure out the ages, but they used to call him the guy who eats all the ice cream. He’d raid the refrigerator and eat all the ice cream and then go to sleep on the couch, even though we had a bed for him.

Riley

And your associations with him through this time are all personal, or is he tapping you for your expertise on international affairs?

Talbott

I wouldn’t put it—nothing like that formal. He was always interested in Russia. He made his first trip to Russia the year after I made my first trip to Russia. I had come back and said it was a great experience, gave him the names of some people, and he and Mark Lackritz, who was a retired association president here in town, and one other guy, maybe Bill Drozdiak, who was the head of the American Council on Germany. I think Drozdiak was involved. Anyway, they made a trip of their own. You know that some of his opponents tried to make an issue out of it. That was a year after—because I urged him to do it. So he always associated me with Russia. There were always interesting things going on in Russia and so we’d talk about it. But it wasn’t like, help me develop my policy on Russia.

Now, when we got into the campaign in ’91, not ’92 but ’91, and the shit hit the fan in Moscow and there was a coup and all that, Clinton was on the phone to me a number of times.

How do I handle this?

He knew that one reason he had his chance to knock off Bush was because the Cold War was over, but maybe the Cold War wasn’t going to be over if the commies had come back. So he was real concerned about that. That’s the only real substantive interaction we had then.Riley

Let me pose a question to you.

Talbott

You should know by way of background that my wife was working for Hillary.

Riley

She had gotten to know Hillary really well?

Talbott

In ’71, that trip that we made to—

Riley

No kidding. So they stayed in touch from—

Talbott

Oh, yes. Then Hillary was on the board of the Children’s Defense Fund. Marian Wright Edelman, I think she stayed at our house a couple of times. Since this is history, I’ll just say it, it sticks in my mind. She was so dogged and determined about doing her job right. She was defending, or prosecutingit must have been defendinga woman who had been raped. She was carrying around a plastic bag with something in it of a very intimate nature that somehow she pulled out at one point and said,

We have the evidence here.

Yikes. You get the drift.Riley

Sure.

Talbott

This was taking her homework home to an extent that I found to be memorable.

Riley

I can imagine. What I wanted to ask you was something that we touched on in the first interview and, under the circumstances, I think it bears elaboration on, and that is there is a perception that I think has some grounding in it that Clinton was somebody who did not have foreign policy experience when he became President of the United States, and yet you knew him as somebody who was very cosmopolitan, not very by your standards, but by normal U.S. politician standards, somebody who was cosmopolitan, who had traveled abroad, had lived abroad. Can I get you to think in terms—

Talbott

You’ve got it right. He was the Governor, had been the Governor for a long time of a less-than-cosmopolitan region of the United States, but even as Governor he had made several trips to Asia drumming up business for, I assume, Arkansan agriculture.

Riley

A lot of chicken.

Talbott

Right, what’s the name?

Riley

Tyson’s.

Talbott

Right, big time. Jim Blair was the general counsel of Tyson’s, a great friend of his. His late wife was a Brookings fellow, Linda Blair. But the other thing was, he’d lived in England for two years during the [Harold] Wilson administration. He’d traveled on the Continent, been to Russia. Vietnam was a kind of an education in foreign policy. So I just always thought, give him a break on that.

Now, where it gets trickier is that he ran against a foreign policy President on the grounds that the foreign policy President was spending too damn much time on foreign policy and didn’t know how checkout bar codes worked, and things like that. So he was going to attend to the American economy; it’s the economy, stupid. But to his credit, and I think, frankly, bringing me on to do what I did in Russia was an example of it. He didn’t say I’m going to pay no attention or I’m just going to delegate out foreign policy, and I don’t think there was ever a time when he resisted advice to get personally engaged. Sometimes if we wanted to make a call at 8 o’clock in the morning, not to mention 7 o’clock in the morning, there were other issues. He is not a morning person. He used to call me at 12, 1 o’clock in the morning, and I’d been asleep for four hours and be getting ready to get up around then. But my point is that he was always ready. I think it was Dean Rusk or somebody who once said that foreign policy for an incoming President is a rich, ripe melon they really want to cut into and enjoy. I think Clinton was like that.

Riley

You think he was like that.

Talbott

Yes. He loved it; he loved that stuff. And he was good at it. He was just a natural diplomat. Goes back to the hard power/soft power.

Riley

Right.

Talbott

Getting people together, working deals.

Riley

So his natural inclination when he comes into the White House is not to focus like a laser on the economy?

Talbott

Well, he wanted both. There’s a chapter, which we can give you, Katie and I, from the most recent book, The Great Experiment, called

The Theory of the Case.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

Where I, after the fact, reconstruct what his world view was. So maybe if you could just—

Riley

That would be helpful.

Talbott

We’ll shoot a copy down. In fact, actually the one, Katie, I can’t—[side chatter looking for book?]

Katie

I ordered a hundred more books, so you can take mine.

Riley

Thank you. If I’ve looked at that, it has been a long time. What year was this?

Talbott

Three years ago.

Katie

The revision was just last year.

Riley

But the chapters that you’re flagging were in the original volume?

Talbott

Oh, yes.

Riley

A loose end about Oxford. Just to get your comments. Cliff Jackson was an Arkansan at Oxford at the same time. Did you know Cliff Jackson?

Talbott

He claims so, and I guess I did. But when he reared his ugly head, which was in ’91, ’92?

Riley

Yes, it would have been right around, at some point as the campaign was unfolding.

Talbott

I remember Clinton saying,

What do you remember about him and blah, blah, blah?

I just didn’t have a recollection then of him other than yes, there was a guy like that but I just didn’t pay any attention to him.Riley

Didn’t pay any attention to him.

Talbott

I was no help, except on the draft issue. I was a firsthand witness.

Riley

You mentioned Bob Reich before.

Talbott

Yes.

Riley

What can you tell us about his relationship with Clinton and the evolution of it, because it—

Talbott

I think you should get it from Bob, and he has of course written a whole book on it.

Riley

Locked in the Cabinet.

Talbott

Out of the closet. No, that’s not right. [laughter]

Riley

Now you are telling us something.

Talbott

It saddens me, and I blame both of them, and a little more Bob. Bob and I are still very close friends. He just was disillusioned with Clinton. I think particularly on, is it Social Security? Yes, I think it was Social Security. Bob is a dyed-in-the-wool liberal and Bill’s triangulation and all that was ideologically unpalatable to Bob. It was much more that. But they were just wonderful friends and hilarious as a couple, if I could put it that way. Bill was 6 feet 2 inches and Bob is 4 feet 10 inches, or something like that. I don’t think he’s even five feet.

Riley

He’s not.

Talbott

Both are great talkers.

Riley

You were surprised that the relationship would founder over politics?

Talbott

No, I think it foundered over policy. Not to be pedantic, but Bob just wasn’t comfortable with the decisions that Bill was making.

Riley

Sure.

Talbott

But Bill, he could get mighty angry. I can remember being in—Brooke [?], who was doing Hillary at the time, had me up to Clinton’s suite in whatever hotel the Clinton party was in at the ’92 convention in New York. We were there with various retainers, passing around drinks and doing things like that. One thing about Clinton is he virtually never drank. Bill Bradley came on the screen and he was still a candidate—he wasn’t a candidate still at that point? Was Bill Bradley—I can’t remember, for the nomination.

Riley

Which year?

Talbott

In ’92.

Riley

I don’t think so. Only in a very remote way.

Talbott

Well, Clinton, you could see a hardness come over Clinton’s face because he regarded him as a rival. Yet he had the nomination sewed up at that point. I didn’t quite understand that, but boy, he was the most—I’ve got to be careful. He had a competitive streak in him that would come out in situations like that. This is a bit of a contradiction but I think it is a resolvable one. I can remember once, it may have been Thanksgiving of ’92. One reason that Christopher—well, see, Christopher decided to make me Deputy Secretary of State. A lot of people assume that Clinton told Christopher to put me in; not at all. Christopher had to sell the idea to Clinton, and to Hillary, who wasn’t initially very enthusiastic about it. She had pushed Cliff Wharton and she was pissed off about the Bobby Inman thing.

One reason Christopher wanted me to be his deputy is because he was having some crisis and tried to reach me over the Thanksgiving weekend and I was out at Camp David. He hadn’t been invited to Camp David, at least not for a while. He said Strobe is loyal and I want him as my deputy because it will be a way of compensating for my own lack of access. How did I get into that? Bowling.

We had the kids with us and we were down in the bowling alley at Camp David. A couple of the bears, as they were called

The Bears,

the [Hugh and Tony] Rodham boys, brotherswere there. Talk about informal. Clinton got so serious about proper bowling form and how to do it right and got so angry at somebody. It may have been me, I forget, but how to do it right. It had to do with scoring. We had teams and whoever it was, whether it was me or somebody else, had a gutter ball and as a result he was going to lose, right? Because his partner—and he was furious. So he had that streak about him.But he also had this forgiving quality, I think very dramatically evident politically with Newt Gingrich. You know Newt Gingrich came into him shortly after the Monica thing and said,

We’re going to run your ass out of town.

This is on the record. Clinton said,No you’re not, but before we see whether you’re right or not, let’s still do some stuff.

So he had this funny combination. He could be very tightlipped and change complexion and just go for something, but then it could also blow over real fast.Riley

Did you ever see this in the foreign policy arena? Were there people who he dealt with—

Talbott

Foreign leaders?

Riley

in the global arena who set his teeth on edge or where he felt that he was being boxed in in a bad way because people didn’t understand his realities?

Talbott

Not that comes to mind. It’s a very good question. Not really. He has—this is a comparison where [Barack] Obama comes off way second best.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

Clinton has an extraordinarily wide bandwidth with regard to his ability to relate to, understand, other people. He can get along with and do business with people who are very different from him, kind of read them, figure out what makes them tick. It is this empathetic quality.

Riley

And this is true. It worked in the same way in the foreign policy arena, you’re suggesting?

Talbott

Absolutely. In fact, I think more so there because he didn’t haveI’m just trying to think. I’m thinking of [indecipherable], for example. I saw him with him a couple of times. That was a relationship that got off to a very bad start, as you may recall, but they were doing fine before too long. I mean, he liked some more than others, but I don’t remember him ever having—I gather Obama does have this—I don’t want to have to deal with that son of a bitch. I never felt that—with Clinton, it comes with the territory. Well, that’s the leader of that country so I’ll have to deal with it.

Riley

Were there instances where his empathies misdirected him or miscued him in the foreign policy arena?

Talbott

Yes, I’m sure there were. But I don’t think I’m so protective of him that if there were such that really mattered, I would be suppressing it.

Riley

Does [Yasser] Arafat come to mind?

Talbott

See, that’s not—first of all, I was in deep shit with the hard-line, right-wing Jewish community. They tried to block my confirmation. [Benjamin] Netanyahu lobbied against me. I was kept way the hell out—

Riley

That was rooted in what, Strobe?

Talbott

Columns I’d written for Time whacking Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon.

Riley

So you’re basically walled off from the Middle East.

Talbott

Totally, and delighted to be. I only went to Israel once and it was to talk to Shimon Peres about Russia. I had nothing to do with the Middle East. I can’t comment on that. But Martin [?], my colleague here, and Dennis Ross, I’ve talked to lots about that. I think Arafat drove him crazy, of course, at Camp David because he wouldn’t take the goddamn deal. But that’s different from what you’re asking about. You’re asking whether this quality of empathy led him to mess up in some fashion.

Riley

Exactly.

Talbott

I would say no.

Riley

Nothing in post-Soviet Russia or eastern Europe?

Talbott

No, the relationship that really mattered was the Yeltsin relationship.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

It was exactly the opposite. Clinton got Yeltsin to do stuff that was politically radioactive for Yeltsin to do. He got him to do it because Yeltsin trusted him. Bill, my friend Bill, won’t see it my way but he’s not going to screw me. I know exactly what you’re asking and if I could think of an example of it, just trying to think on the Far East, the Balkans, it really didn’t come up. No.

Riley

Nothing in Europe?

Talbott

His most important relationship with Europe was probably with Helmut Kohl, and birds of a feather, pigging out at whatever that Italian restaurant in Georgetown is, and doing a lot of good stuff. [Jacques] Chirac, he didn’t like Chirac very much. Chirac was very condescending towards him. But that wasn’t a big deal.

Riley

So his natural empathies were actually—

Talbott

Yes, I think he got along great with Tony Blair. There was no Italian Prime Minister long enough to matter during that period.

Riley

His relationship with Blair was a little different though, right, because Blair was, I wouldn’t say junior to him, but Blair comes in later—

Talbott

And kind of clintonesque too.

Riley

Right.

Talbott

He regarded Blair as a protégé. Anyway, I’ll think on these questions but I honestly don’t—and his critics, I mean, I’m sure there are people who will say, I don’t know what they would say, because he overempathized, he therefore got us into this, that, or the other trouble, no.

Riley

All right. What about terrorism as an issue? It now takes on a much greater historical importance during the eight-year term.

Talbott

Let me give you—because I know our time is limited. I’ll give you my own compressed answer, but there is an awful lot on the record. Sandy, as we know, was very diligent about trying to compile a record of everything, and that record exists and it is a public document. You ought to get hold of that. I think maybe Larry Rawson or Jeremy Rosner, but Sandy is the guy to go to and just get the big, thick thing that goes tickety, tickety, tick. Here’s how I remember it.

It goes all the way back to the blind sheik and the first World Trade Center thing. It was a big deal and it got to be a lot bigger deal. I forget the order in which they happened, but the African embassy bombings and the Cole. I was, and this may be publicly available, I was interviewed at great length because you don’t have subpoena power. They did, by the 911 Commission. I think that’s a publicly available document.

Riley

I think so too.

Talbott

So you might just get that and attach it to the record.

Riley

Will do.

Talbott

But the point of it was, I did not do terrorism except insofar as it was on the agenda of my dialog with the Pakistanis. That’s really the only time—and there I was more concerned about nukes. But what I remember vividly from that whole time is that notionally half the meetings I went to at the White House—none of the meetings I went to at the White House were on terrorism per se, I don’t think, with the possible exception of after the African bombings. But at at least half of the meetings, terrorism came up. So it was a constant issue.

George Tenet, I must have heard him brief us on what we knew about Osama [bin Laden] and what we were trying to do. I was on the fringes of the—oh, yes, I was more than on the fringes of the decision to try to take Osama bin Laden out with some cruise missiles right after the African bombing. So the notion that we were somehow asleep at the switch, we didn’t hit the right switches at the right time, but it was a huge deal. But Sandy is a much better source on that because he was living it and breathing it.

Riley

I’m about out of time. Let me ask you this sort of global question. Thinking back, are there two or three instances where in your experience with President Clinton he really took a pivotal decision that clearly has the markings of being a pivotal decision? History helps turn in a particular area. I’m thinking more in terms of specific instances rather than an overall or general approach. Maybe you’ve addressed this in your book and I’ve just missed it.

Talbott

Yes.

Riley

I’m interested in what those critical decisions are, from your perspective, and maybe what they help illuminate about Bill Clinton’s turn of mind.

Talbott

I think we’ve already touched on them in a way. I think the decision to use force to reverse a military coup and restore democracy in Haiti was a very important decision, and the accompanying diplomacy, which Madeleine [Albright] deserves a huge amount of credit for, of getting the UN [United Nations] to go along with that was a big deal. I think the decision to work with Russia insofar as that was possible during the run-up to and then the wind down from the Kosovo War was very big. Enlarging NATO. At a lower tier, taking APEC [Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation] up to the leaders’ level was important in terms of he had a notion of global architecture, that wasn’t the phrase he used for it.

I guess you can’t quite put the Middle East on the list because it failed, but I do think that his determination to bring as much of the post-Soviet world as possible into the political west was big.

Riley

This occurs over your—

Talbott

Just to finish the thought, but a key element there goes to personality and personal chemistry.

Riley

Okay.

Talbott

Having Boris Yeltsin as the President of Russia during that time is one of these minor miracles of history because you can imagine a lot of people having been the leader of Russia. I think, by the way, [Ronald] Reagan and [Mikhail] Gorbachev you could say the same; Bush 41 and Gorbachev. But those were—that was sort of a trifecta. Those three American Presidents having those two Soviet/Russian counterparts was very important.

Riley

The personal chemistry you’re saying is—

Talbott

Critical.

Riley

It’s critical there.

Talbott

There’s a lot of PolySci [political science] shit about it’s systems and it’s governments that interact, and people sort of add at the margins. It’s just not true.

Riley

That’s a wonderful gem to close on. One of my senior colleagues who is a political scientist says political scientists don’t know what to do with people, and it’s true, I think, by and large. One of the things we discover during our interviews is that people do matter.

Talbott

Yes, I had a courtesy appointment in the Yale political science department and I kept saying it certainly is an interesting theory, but golly it doesn’t bear any resemblance to what I’ve seen. But you don’t understand what you’ve seen. What is your discipline?

Riley

I was trained in the government department at the University of Virginia as a political scientist, but the department has forever avoided the designation political science department. It calls itself Department of Government.

Talbott

I want to say two things then we’re free. One is, if you want to follow up at some point I’m happy to do it. Katie will kill me for making the offer but it stands. Second, I’ve been a professional question-asker all my life, I got paid for it for some of my life, and you’re terrific at it. I really admire it.