Resignation was not the end

Today we assume an official who resigns won't face impeachment or a subsequent trial. That wasn't always the case.

On August 9, 1974, Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency to escape impeachment and almost certain removal from office. Watergate, “our long national nightmare,” in the words of President Gerald Ford, was over. And the impeachment process was finished.

Can Congress impeach and try someone who has resigned?

Today, it is hard to imagine an impeachment continuing after the official has departed office. But in the nineteenth century, it was an open question.

During the first federal impeachment proceedings—for Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase (1804), three federal judges, and President Andrew Johnson (1868)—no one resigned. They stuck it out until the very end, resulting in a Senate acquittal or conviction.

The first official to resign under the cloud of impeachment was Judge Mark H. Delahay. President Abraham Lincoln had appointed Delahay in 1863 to serve on the U.S. District Court in Kansas, but Delahay’s drinking problem became intolerable when he continually presided in court drunk. On February 28, 1873, the House of Representatives impeached him for “personal habits unfitted him for the judicial office . . . and that his sobriety would be the exception and not the rule.” Delahay resigned before the Senate could begin his trial, and the matter ceased.

Belknap’s case is the only one in history in which a Senate trial took place after the official in question had already resigned.

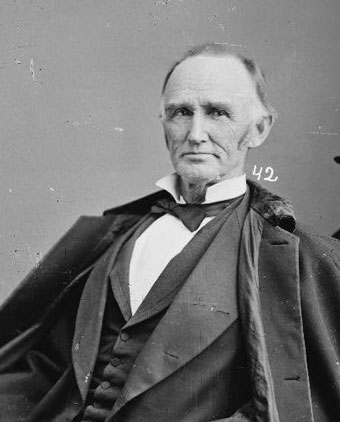

President Ulysses S. Grant faced a much different scenario with his secretary of war, William W. Belknap. Belknap’s case is the only one in history in which a Senate trial took place after the official in question had already resigned.

Belknap’s impeachment saga began in 1870. His second wife, Carrie, enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, and the two of them hosted extravagant parties in D.C. Belknap’s government salary was only $8,000 a year, however, and in order to keep up with expenses, Carrie lobbied her husband to appoint her friend, Caleb Marsh, to run the trading post at Fort Sill in the Oklahoma Territory. Eventually Marsh made a deal with the current occupant of the office, John Evans. Evans would pay Marsh around $12,000/year to keep the post. And since Marsh was using the Belknaps' influence to extort the money, he agreed to give half of it to them.

This scheme continued after Carrie died. Belknap remarried in 1873, and by 1876, he had collected over $20,000 (nearly $480,000 in today’s dollars). In February 1876, however, The New York Herald discovered the arrangement and broke the story.

Rep. Hiester Clymer (D-PA), chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Department of War and an opponent of the president and his Reconstruction policies, began to investigate, and on February 29, Marsh admitted to the deal in sworn testimony during a secret meeting with only Democrats in attendance.

Belknap offered to admit to the bribes, but only if the committee agreed to hide his wife’s involvement.

The following day Belknap offered to admit to the bribes, but only if the committee agreed to hide his wife’s involvement. When the committee refused, he left without testifying. The scandal was quickly turning serious, and on March 2, a member of the committee, Rep. Lyman Bass (R-NY), met with Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow. Bristow then went to talk with Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, who told him to see Grant at the White House immediately.

At the White House, Bristow told the president that he should talk with Bass without explaining why, but as Grant began to leave, a steward told him that Belknap and Secretary of the Interior Zachariah Chandler were waiting for him. Nearly in tears, Belknap told the president that he must resign at once. Grant agreed, and as he tried to leave a second time, Senators Oliver Morton (R-IN) and Lot Morrill (R-VT) urged him not to accept the resignation: The House had just impeached Belknap. (Three of the five articles had passed by unanimous votes.)

Despite Belknap’s resignation, Democrats wanted to proceed: A Senate trial would keep the Republican scandal in front of voters, and House leaders believed that an official should not be able to evade justice simply by resigning. The House elected seven managers and prepared to send the five articles to the Senate. The trial began on April 5, 1876.

For nearly a month, the trial focused on whether Congress had the jurisdiction to try a private citizen, as Belknap now was. The former secretary’s legal team argued that the appropriate venue now was a criminal court, not a Senate trial. They also noted that none of the founders in all the debates on the Constitution had ever referenced the impeachment of private citizens.

In contrast, the House managers (two of whom were Republicans) argued that Belknap had resigned knowing that the House was going to impeach him, that he had committed his crimes while he was secretary of war, and that a trial would prevent him from holding federal office in the future. Both removal AND disqualification, they said, were the point of a trial, and while Belknap had removed himself, he needed to be disqualified.

Belknap’s team countered that since Belknap had already left office, the Senate couldn’t remove him OR vote to disqualify him. One of Belknap’s lawyers, Montgomery Blair, explained: “You cannot pronounce a judgment of removal without disqualifying, and you cannot pronounce a judgement of disqualification without removal, because the judgment which the Constitution requires you to pronounce is a judgment of removal and disqualification—not removal or disqualification.”

On May 15, the Senate voted 37 to 29 to continue with the trial, but the tally did not reach a two-thirds margin necessary for conviction, Belknap held out hope as the trial turned to issues of guilt or innocence. And indeed, when the Senate held its final vote on August 1, the 37 to 25 guilty vote was short of the necessary two-thirds with the votes falling mostly along partisan lines: Democrats voted guilty, while the majority of Republicans voted that the Senate did not have jurisdiction.

Though the trial had continued, the precedent did not. Fifty years later, when Judge George W. English resigned during his Senate trial, the proceedings stopped. The same, of course, held true for Richard Nixon. When Senator Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) and other top Republican congressional leaders came to the White House to meet with Nixon, they knew that if the president resigned, the impeachment process would be over. Congress had finally decided: impeaching a private citizen was going too far.