How to recage the executive lion

‘The British system provides helpful examples of how to handcuff a grasping executive’

The following is excerpted from the introduction to The Living Presidency, by Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash, Copyright © 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved

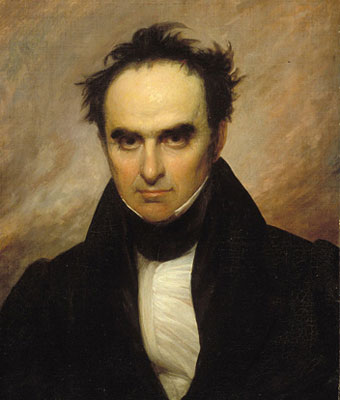

During Andrew Jackson’s presidency, statesmen like Henry Clay and John Calhoun condemned what they saw as Old Hickory’s overreaches. Although many of their criticisms were ill-conceived, we can learn a thing or two from the likes of such giants. One cutting critic, Daniel Webster, insisted that in the “contest for liberty, executive power has been regarded as a lion which must be caged. So far from being . . . considered the natural protector of popular right, it has been dreaded, uniformly, . . . as the great source of its danger.” In his view, only “watchfulness of executive power” could safeguard our liberties.

On his last point, “Godlike Daniel,” as he was known in his time, was right. We must not lose hope; rather, we must be vigilant and fight back. Those in favor of the limited presidency of the Founding must be counter-revolutionaries and struggle against the self-serving, creative energies of our presidents and their allies.

We can learn from the past, including our British American past. Our current predicament is best conceived of as replicating, in certain ways, the British constitution of old. The British constitution of the eighteenth century lacked our canonical text and was instead conceived of as the sum of disparate parts—laws, practices, and conventions. While certain features of the constitution might remain fixed for long periods, others fluctuated in the face of politics and changed circumstances. Nothing was permanent. Under that fluid system, there were periods when monarchs grasped for power and sought to upset the status quo. Sometimes they were successful, and other times they failed. The overall trend, though, was that the monarchy weakened and the legislature assumed the executive functions, so that now the Parliament practically has the entire legislative authority, and a portion of Parliament—the ministers—are the real executive. The reigning monarch of the United Kingdom is all pomp, circumstance, and tabloid fodder, with no real appetite to exercise whatever remaining powers rest formally in her hands.

We too have a British-style constitution, where new practices and understandings may supersede everything that is old.

Although the US Constitution was supposed to be fixed, and each of the three branches were to be legally bound to it, the reality is that we too have a British-style constitution, where new practices and understandings may supersede everything that is old. Though our Constitution’s text has been relatively fixed, much of the unamended text has been reinterpreted and reimagined to yield wholly new meanings that would have been unfamiliar, even alien, to the Constitution’s Founders. Because we do not see many formal changes to the Constitution, many of us suppose that we are ruled by the original version, albeit with some important amendments. But even if most of the provisions in the Constitution were never formally amended, many of their meanings have changed in ways that have effectively amended the original document.

If a British-style unwritten and flexible Constitution has largely supplanted the Founders’ written and fixed Constitution, the British system provides helpful examples of how to handcuff a grasping executive. At various points in English and British history, institutions have pressed for reforms and fought to preserve and extend them through sheer doggedness. The Parliament, the courts, and others have labored to box in executive authority. Celebrated charters of liberty—the Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights, the English Bill of Rights, and the Act of Settlement—have curbed the Crown’s propensity to usurp legislative authority, impose its will on the judiciary, and invade individual liberty.

American history is likewise littered with examples of Congress pushing back against executive overreach. Consider limitations on the president’s power to fire officers. Whatever one thinks of their constitutionality (I am dubious), federal laws limiting the executive’s power to remove federal officers (“for cause” laws) are ubiquitous and represent sustained efforts to curb presidential authority. These laws have been successful, for modern presidents respect these limitations and almost never even try to remove such officers.

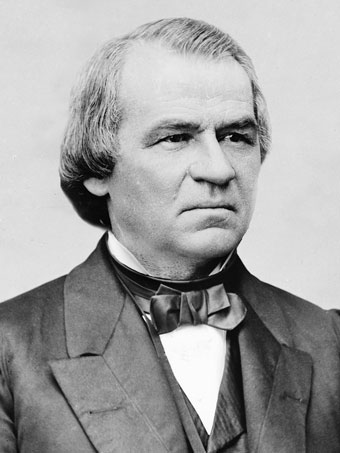

During Reconstruction, Congress sought to restrain President Andrew Johnson’s authority over the military bureaucracy. Because legislators perceived him as too soft toward the South, they passed laws to weaken the presidency. For instance, Congress barred the president from directly ordering subordinate military officers; instead all his orders had to be routed through the general of the army, Ulysses Grant. This was clearly designed to weaken the president’s ability to direct the military and supervise military reconstruction of the South. Again, whether constitutional or not, such laws represented a counterreaction. Furthermore, after the House impeached Johnson and the Senate came within a hair’s breadth of convicting him, Congress found that he was more docile and agreeable. The draining and harrowing experience had curtailed Johnson’s appetite for confrontation.

With the bombing of Cambodia, the firing of Archibald Cox, the destruction of Oval Office tapes, and the Watergate burglary still fresh memories, Congress moved to rein in the executive.

A third instance of congressional pushback can be found in the Nixon and Ford years, when Congress enacted a slew of reforms. With the bombing of Cambodia, the firing of Archibald Cox, the destruction of Oval Office tapes, and the Watergate burglary still fresh memories, Congress moved to rein in the executive. It passed the 1973 War Powers Resolution to curtail presidential war-making. In 1974, Congress by law required the president to notify certain legislators of covert action. That same year, it also approved the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act to limit executive refusals to expend appropriated funds. It passed the 1978 Ethics in Government Act, with its creation of independent prosecutors to investigate and prosecute high ranking executive officials. For a moment at least, Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s “imperial presidency” seemed to have abdicated. Or as Gerald Ford put it in 1980, the presidency had become “imperiled” instead of imperial.