Bush v. Gore

The 2000 election was decided by a razor-thin margin in the state of Florida and a landmark Supreme Court decision

This essay was adapted from George W. Bush: Campaigns and elections.

After George W. Bush easily won reelection as governor of Texas in 1998, many national political figures urged him to run for the presidency. On the morning of his second inauguration as governor, Bush told his mother that he was still struggling with the decision. She was not sympathetic, suggesting that her son should simply decide. The church sermon that day described the calling of Moses by God to lead his people from Egypt. During the service, Bush’s mother leaned toward him and said, “He is talking to you.” Bush authorized Karl Rove to begin preparing for a national campaign.

The clarity Bush may have felt was not enjoyed by Gore.

Al Gore was finishing his second term as vice president, the heir apparent to President Bill Clinton when he entered the 2000 campaign. But the clarity Bush may have felt was not enjoyed by Gore. The year 1998 had been fully consumed by a Congressional investigation and impeachment of Clinton over his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky—and subsequent lies about it. Clinton had been acquitted in the Senate by the time Gore announced his candidacy, but the vice president was at pains to distance himself from his boss saying, “With your help, I will take my own values of faith and family to the presidency to build an America that is not only better off but better.” He mentioned Clinton but once in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention. And as the campaign progressed, he kept Clinton largely on the sidelines.

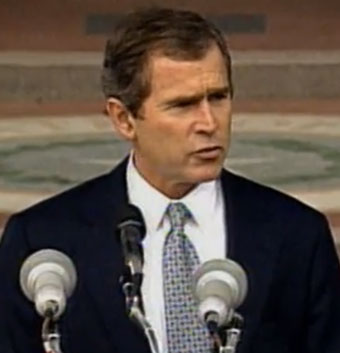

National name recognition, family connections, and fundraising ability made Bush a strong presidential candidate. The 2000 Republican National Convention was held in Philadelphia, where Bush delivered a stirring speech that reflected his reasons for pursuing the presidency: “Our opportunities are too great, our lives too short to waste this moment. So tonight, we vow to our nation…we will seize this moment of American promise. We will use these good times for great goals. …This [Clinton-Gore] administration had its moment. They had their chance. They have not led. We will.”

Moderated by PBS’s veteran anchorman Jim Lehrer, the first debate between Bush and Gore took place in Boston. Bush made a consistent effort to paint Gore as a Washington, D.C., insider who made big promises and showed few results; Gore attempted to portray Bush as a friend of the rich with little experience in governing, especially at the federal level. Neither candidate committed any major gaffes, and both hewed to their prepared scripts. Inexplicably, Gore audibly sighed at several of Bush’s responses. Violating the debate rules, the vice president frequently interrupted his opponent. Gore’s tactics seemed over-eager and unprofessional. The second and third debates went smoothly, without major gaffes from either candidate. Polls suggested that Bush benefitted more from the televised debates, showing that voters felt better about a Bush presidency than a Gore administration.

Not disclosing the DUI on my terms may have been the single costliest political mistake I ever made.

George W. Bush

Governor Bush felt optimistic about his chances before adviser and confidant Karen Hughes approached him five days before the election with news that a reporter had discovered a drunk driving citation Bush had received years ago. Bush had considered disclosing the DUI earlier in his political career but decided against it because, as he claimed, he did not want his daughters to know about his irresponsible behavior. “Not disclosing the DUI on my terms may have been the single costliest political mistake I ever made,” Bush later wrote. Laura called their daughters to inform them of the announcement before they found out from television news. Bush issued a pithy statement: “I was pulled over. I admitted to the policeman that I had been drinking. I paid a fine. And I regret that it happened. But it did. I’ve learned my lesson.”

Bush worried that he might have cost himself the presidency. Karl Rove estimated that approximately three million people, especially evangelical Christians, stayed home or changed their vote following the disclosure. During the five days following the announcement, Bush lost the four-point lead he had held in the polls. He campaigned hard for the last week and entered election day with the race too close to call.

On election night, the major news networks initially called the key battleground states of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Florida for Gore. Florida’s polls had not even closed, and Karl Rove adamantly maintained that the early call was flawed. At about 10 p.m., Eastern time, CNN and CBS rescinded their early call of Florida, and at about 2:15 a.m., the networks revised their call of the race in Florida in favor of Bush. Shortly after the Florida switch, Gore phoned Bush to concede. Gore had about fifteen minutes to address his supporters before Bush would speak to the crowd waiting outside the state capitol in Austin, Texas. The allotted time passed without a concession speech from Gore. Bush’s brother, Governor Jeb Bush of Florida, checked the networks to find that the margin in Florida was narrowing once again. Subsequently, Bush spoke with Gore again via phone, and in a terse conversation, Gore told Bush that he was retracting his concession as the numbers in Florida kept changing.

By 4:30 in the morning, the Bush campaign discovered that Gore had sent a team of lawyers to Florida to oversee a recount of the votes. Bush was advised to send an emissary as well and dispatched Washington powerhouse and former secretary of state, James Baker, a veteran of the Regan and Bush 41 administrations.

After weeks of legal battles and recounts, the Florida Supreme Court ruled 4-3 in favor of Gore’s plea for a selective recount. Bush then appealed to the United States Supreme Court. On December 12, the high court ruled in Bush v. Gore. By a vote of 7-2, they found that Florida’s inconsistent recount process violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution’s 14th amendment. More decisively, by a 5-4 decision, the Court ruled that there was no fair way to recount the votes in Florida in time for the state’s votes to be counted in the Electoral College. The election results would stand. By just a few hundred votes, Bush had won Florida and with it the presidency. He had wanted to share the victory in Austin with his 20,000 supporters waiting on election night, but, as he wrote, he “probably became the first person to learn he had won the presidency while lying in bed with his wife watching TV.”

It's time for me to go.

Al Gore

Gore responded the following evening with a clear concession. “Let there be no doubt, while I strongly disagree with the court's decision, I accept it. I accept the finality of this outcome, which will be ratified next Monday in the Electoral College,” adding “I particularly urge all who stood with us to unite behind our next president,” and ending memorably with “it’s time for me to go.”

The national spectacle of the Florida recounts, with its disputed ballots, “hanging chads,” and determinative Supreme Court ruling, undermined Bush’s wish to start his presidency with a strongly united nation. While he won an Electoral College victory 271 to 266, Gore won 500,000 more popular votes from the American people than the victor. Many considered Bush’s election to be illegitimate, and the Congressional Black Caucus even protested during the official counting of the ballots on the floor of the House of Representatives. It was a less than auspicious start for any new presidency.