Watergate and the decline of constitutional restraint

The scandal left the presidency caught in the crosshairs of growing partisan conflict

Excerpted from What Happened to the Vital Center? by Sidney Milkis and Nicholas Jacobs (Oxford, 2022)

Richard Nixon’s embellishment of the executive administration provided an opportune moment for collectively-minded members of Congress to recommit themselves to the hard but necessary work of institutional maintenance. Faced with a hostile president who sought to enact change primarily through unilateral power, Congressional Democrats attempted to reinvigorate the system of checks and balances by altering chamber procedures and reorganizing the committee structure. To be sure, much of the incentive for legislative reorganization, which strengthened the legislative and oversight capacity of subcommittees, was the result of the lingering animosity liberal members felt toward seniority norms for ceding too much power to Southern members of the Democratic caucus, who year-after-year returned to office from their safe districts.

Democrats, nevertheless, also set their sights on the “imperial” presidency in several consequential ways. First, as the White House reorganized the Budget Bureau into the modern day Office of Management and Budget, Congress reorganized so as to more efficiently divide the workload and oversight functions of its several standing committees. Significantly, the decision to devolve more power to subcommittees also came with Congressionally-authorized spending increases for committee staff and research services.114 With the war in Vietnam dragging on, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution in 1973, which required presidents to notify and seek approval from the Congress in order to commit troops to combat. Finally, in response to Nixon's decision to impound, or not spend, Congressionally-appropriated funds for several liberal programs, Congress passed the 1974 Budget and Impoundment Control Act. This presidency-curbing legislation not only stripped the president of a self-declared prerogative to restrict spending (upheld one year later by the Supreme Court), it also strengthened Congress's role in preparing a budget and evaluating policy alternatives by establishing standing budgetary committees and the Congressional Budget Office.

Democrats, nevertheless, also set their sights on the “imperial” presidency in several consequential ways. First, as the White House reorganized the Budget Bureau into the modern day Office of Management and Budget, Congress reorganized so as to more efficiently divide the workload and oversight functions of its several standing committees. Significantly, the decision to devolve more power to subcommittees also came with Congressionally-authorized spending increases for committee staff and research services.114 With the war in Vietnam dragging on, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution in 1973, which required presidents to notify and seek approval from the Congress in order to commit troops to combat. Finally, in response to Nixon's decision to impound, or not spend, Congressionally-appropriated funds for several liberal programs, Congress passed the 1974 Budget and Impoundment Control Act. This presidency-curbing legislation not only stripped the president of a self-declared prerogative to restrict spending (upheld one year later by the Supreme Court), it also strengthened Congress's role in preparing a budget and evaluating policy alternatives by establishing standing budgetary committees and the Congressional Budget Office.

These three reforms equipped Congress during the 1970s and 1980s to challenge the modern president’s preeminence in legislative affairs. As R. Shep Melick has written,

Using subcommittee resources, members initiated new programs and revised old ones, challenging the president for the title of “Chief Legislature.” No longer would Congress respond to calls for action by passing vague legislation telling the executive to do something. Now Congress was writing detailed statutes, which not infrequently deviated from the president’s program. Subcommittees were also using oversight hearings to make sure that administrators paid heed not just to the letter of legislation, but to its spirit as well.

However, this assault on the modern presidency did not really restore checks and balances; rather, it revamped the Madisonian system for partisan confrontation. When new Democratic members—the "Watergate Babies"—entered Congress in 1975, they used the new rules to challenge the party's leadership and strengthen the caucus's commitment to the causes and policies of post-New Deal liberalism. The imperial presidency had hardly become imperiled, as some critics of the Democratic Congress claimed; but it was caught in the crosshairs of growing partisan confrontation.

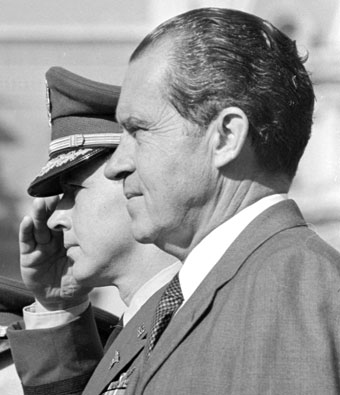

Republicans defended Nixon and his aggressive use of the administrative presidency to further conservative objectives.

Republicans responded by redoubling their commitment to executive-centered partisanship. They defended Nixon and his aggressive use of the administrative presidency to further conservative objectives. When the president's office took its electioneering and partisan mobilization strategy too far—ordering the break-in of the Democratic National Committee's offices at the Watergate Complex—Republicans did not challenge the premises of the prerogatives that had accrued to the modern executive office. In a now familiar refrain, Gerald Ford, when serving in the House, denounced Rep. Wright Patman's (D-TX) Committee to investigate Watergate as a "political witch hunt."

President Nixon addresses Watergate in his 1974 State of the Union

As newspaper reports dug deeper, Senator Robert Dole picked up on the White House's frequent attacks on the media and claimed that the entire Republican Party had been "the victim of a barrage of unfounded and unsubstantial allegations by George McGovern and his partner in mud-slinging the Washington Post." A majority of Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee voted against recommending the several articles of impeachment to the full House, citing insufficient evidence. Only when the White House tapes proved otherwise did Nixon’s partisan allies jump ship.

The Iran Contra Affair nevertheless placed Republicans in a similar predicament of having to defend an administration that willfully violated Congressional law.

Watergate was not an isolated event. Just over 12 years later, news broke that the Reagan White House had knowingly funneled money to support the anti-communist Contras, thus violating the Boland Amendment which proscribed such aid. While less narrowly political in nature than the robbery ordered by the White House-run Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), the Iran Contra Affair nevertheless placed Republicans in a similar predicament of having to defend an administration that willfully violated Congressional law. In the middle of the Reagan presidency, Theodore Lowi offered a prescient analysis of the dilemmas of modern presidential governance that would routinely lead Republicans to denigrate constitutional restraint in a partisan defense of a constitutional office: an institution firmly attached to a party that staked all hopes of future victory on the legacy of a single man with an impossible job. "Deceit is inherent in the present structure," Lowi argued. "Since more is demanded than can ever be delivered . . . deceit will always be used to save the president as well as to defend the fundamental interests of the state."

Deceit is inherent in the present structure.

Theodore Lowi