LBJ 'questioned the withdrawal'

The president didn't see bringing troops home as constructive, especially as he intensified the war effort

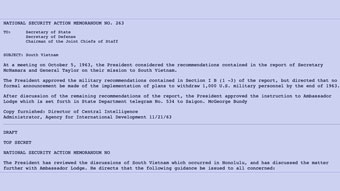

After President Kennedy's assassination, the new president maintained the old president’s policy, despite private misgivings. Media coverage of President Lyndon Johnson’s November 24, 1963, meeting with national security officials reaffirmed the continuity LBJ was desperate to project; as reported in the New York Times, the October 2, 1963, statement on the 1,000-man troop withdrawal “remains in force.”

Johnson was desperate to project continuity, making a statement that the 1,000-man troop withdrawal 'remains in force'

True, that statement was merely aspirational, while its formulation in National Security Action Memoranda (NSAM) 263 was more concrete, directing the Pentagon to withdraw 1,000 servicemen before the year was out. And that is precisely what happened. Consistent with both the October statement and NSAM 263, the initial increment of those 1,000 troops did indeed leave Vietnam.

Speaking prior to their departure on December 3, Military Assistance Command of Vietnam Chief Gen. Paul Harkins indicated that the withdrawal of the first 300 soldiers would be followed over the next few weeks by the remaining 700. Harkins hailed their removal as a triumph—a testament to the ability of U.S. and South Vietnamese troops, to the effectiveness of the advisory relationship, and to the training of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces, which had “progressed to the point where the withdrawal of some U.S. forces is possible.”

The public image of the troops' withdrawal could sustain the appearance of progress, Bundy argued, even if the administration had decided to escalate the war

Johnson was less enthusiastic. Speaking with National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy and Director of Central Intelligence John McCone, LBJ “questioned the withdrawal” of the 1,000 servicemen, as McCone put it. The president “could not see that this was a constructive move in view of the decision to intensify the effort.” Bundy nevertheless was “defending the action.” The public image of the troops' withdrawal could sustain the appearance of progress, he argued, even if the administration had decided to escalate the war.

But appearances were deceiving. Since many of those soldiers returned as part of a “normal turnover cycle," as the Pentagon Papers phrased it, and since additional deployments to Vietnam had been approved during the fall, the United States never did lower the absolute number of advisory troops serving in Vietnam. The 1,000-man withdrawal, as implemented by the Johnson administration, became “an accounting exercise” as troops continued to move in and out of Vietnam as part of the normal sequence of force rotation. In truth, it was hardly envisioned as anything more robust, as both Kennedy and McNamara anticipated it might well become an exercise in creative bookkeeping.

The 1,000-man withdrawal became 'an accounting exercise.' Kennedy and McNamara anticipated it might well become an exercise in creative bookkeeping

The defense secretary did warn against the creation of military units merely for the purpose of withdrawing them, but his position stemmed from a desire to avoid charges of cynicism and opportunism, not from any ironclad interest in preserving a specific balance of logistics to advisory troops. At root, the 1,000-man withdrawal was little more than a symbolic act, as all involved recognized it would be.

Excerpted from THE KENNEDY WITHDRAWAL: CAMELOT AND THE AMERICAN COMMITMENT TO VIETNAM, by Marc J. Selverstone, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2022 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.