Reconsidering Jimmy Carter's legacy

Although Americans did not reelect him, he's long been rated as one of the nation's most admired figures

Jimmy Carter won only 41 percent of the popular vote in his losing bid for reelection to the presidency in 1980. But in the ensuing years, he was routinely rated among America’s most admired figures, finishing in the top 10 of Gallup’s rankings 29 times. (Only Billy Graham and Ronald Reagan fared better.) How is it that a man so thoroughly dismissed when he last faced the voters can be thought of today as one of our greatest American leaders?

The conventional answer is that Carter led an exemplary postpresidential life. He made the admirable decision after leaving the White House that, rather than cashing in on his status as a former president, he would continue his public service in other ways.

With characteristic determination, he immersed himself in solving neglected global health problems. In 2015, remarking on one particularly nasty parasite, he claimed that he wanted “the last Guinea worm to die before I do.” Today that pest is nearly eradicated from the planet.

In 2015, remarking on one particularly nasty parasite, he claimed that he wanted “the last Guinea worm to die before I do.” Today that pest is nearly eradicated from the planet.

That “nearly” may explain Carter’s perseverance during a protracted period of hospice care at the very end of his life. Few people could be better prepared to meet St. Peter than a longtime Sunday school teacher who spent his spare time building houses for the poor. So perhaps Carter’s famous competitive streak kept him clinging to life, in hopes of outlasting a foe he spent decades battling.

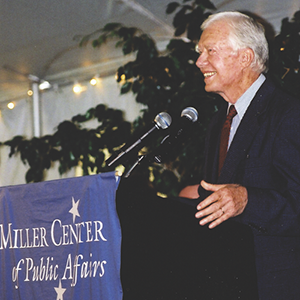

But there is another explanation for Carter’s revived standing at work here, too. Over time, his presidency has looked better than it did when he left the Oval Office. And, not coincidentally, the Miller Center played a prominent role in this reassessment.

“Each presidency nowadays gets studied in two rounds,” observed Professor James Sterling Young, who for decades was the director of the Center’s Program on the Presidency and the creator of the Presidential Oral History Program. The initial evaluation of each president is heavily reliant on contemporaneous journalistic accounts. And this first rough draft of history “tends to become the accepted portrait,” Young observed in 1988.

That initial image of President Carter was decidedly unflattering. To be sure, voters were aware of the most prominent of Carter’s successes: the Camp David Accords, which remain the measuring stick for diplomatic achievement; a record of advancing a more inclusive judiciary; and significant accomplishments on the environment and the expansion of national parks. But these wins were overwhelmed by catastrophic economic news. Gas prices doubled on Carter’s watch. And both inflation and unemployment skyrocketed, leading his opponents to promote a newly invented “misery index,” which rose to the highest levels on record during Carter’s years.

His foreign policy was equally troubled. The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, leading Carter to withdraw U.S. participation from the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. And he suffered the humiliation of hostages being taken from the American embassy in Iran, initiating a nightly ABC News report headlined “America Held Hostage: Day X.” Journalist Ted Koppel gave Americans an empirical reminder each day of the president’s mounting failure, reversed by the hostage takers only at the moment Carter turned the office over to Reagan in January 1981.

This was the Jimmy Carter who first entered the pantheon of former presidents—consigned to the wing populated by the Herbert Hoovers and Martin Van Burens of our collective memory.

This was the Jimmy Carter who first entered the pantheon of former presidents—consigned to the wing populated by the Herbert Hoovers and Martin Van Burens of our collective memory.

But, as Young noted, there is a second round of study. When further evidence about the inner life of an administration becomes available, normally through the long-delayed release of a president’s papers, reassessments become possible, even inevitable. And this is where the Miller Center has been central to Carter’s reevaluation.

Young was not content to await the opening of the presidential documents to begin thinking about Carter’s place in history. He believed in the promise of another resource: in-depth interviews with the people who serve with a president, to create a candid record of their recollections to inform later generations about what life within a given White House was like.

He was also mindful of the great value of the Center’s first excursion into oral history: a confidential group interview with Ford administration alumni (including a very young Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld) recorded just months after they had left the White House in April 1977.

Young wandered the halls of the Old Executive Office Building in the final weeks of Carter’s term, persuading a critical mass of people to agree to participate in such a project. Less than a month after Carter left Washington, a team of people who worked in his Office of Public Liaison under Anne Wexler quietly reassembled in Charlottesville to reflect privately, into a tape recorder, on their ups and downs. Carter himself would host a team of senior scholars less than two years later, in Plains, Georgia, to answer questions for a full day on his own firsthand experiences as president.

The Jimmy Carter Presidential Oral History Project played a meaningful role in creating a second, and more nuanced, portrait of Jimmy Carter and his White House. The caricatures of Carter that sometimes dominated the press accounts—a president obsessed with scheduling the White House tennis courts or under attack by a “killer rabbit” (look it up!)—gave way in these interviews to a serious-minded, honor-driven leader committed to the public good but who had little tolerance for arguments about what was politically viable. By 1990, scholarly reviewers for the journal Polity could assert that the Miller Center’s work had “contributed to the rehabilitation of a president who had been all but left for dead after the election of 1980.”

There were two main components to this revised understanding of Carter. The first was a full recognition of the extraordinarily difficult governing circumstances of his time. Carter was elected to the presidency largely because he was a newcomer to the national scene at a moment when the country was exhausted by scandal and political turmoil.

Carter was elected to the presidency largely because he was a newcomer to the national scene at a moment when the country was exhausted by scandal and political turmoil.

In a secret cable back to London in 1977, British Ambassador Peter Jay described the national mood as “recuperative.” He wrote, “It would be hard to exaggerate the blows to American self-confidence suffered over the dozen years between [John] Kennedy’s assassination and Nixon’s resignation. The pillars of American self-esteem—morality, invincibility, stability, and growth—were all shaken profoundly by the successive shocks of Kennedy’s death, the race riots, the generation gap, the deaths of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the Vietnam failure, the energy crisis, the supposed amorality of [Henry] Kissinger’s foreign policy and the steady rise of Soviet power. The election of Jimmy Carter, the clean pragmatist with a moral purpose, expressed as clearly as anything the yearning of the American people for a fresh start.”

But newness never lasts. And a corollary of that “fresh start” was a constitutional reset: After a decade of executive excess, Americans were weary of the presidency. A class of particularly independent legislators was sent to Congress in 1975—the so-called “Watergate babies”—and so even the president’s own party was resistant to taking direction from a Democratic chief executive. What’s more, every journalist on the White House beat wanted to be the next Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein to bring down a president.

Carter’s institutional problems, however, were compounded by a second factor: his own operating style. Jimmy Carter was—for better and for worse—a president who eschewed conventional politics. Indeed, he was not a politician in the classic sense of that term, with its focus on kissing babies, airy rhetoric, and the oily give-and-take of bartering for votes. His indifference to politics-as-usual helped Carter get elected in the first place. But it made for endless trouble once he got into the Oval Office.

Carter lived for substance. He holed up for almost two weeks, nonstop, with Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin at Camp David in 1978 to negotiate the minute details of a peace plan for the Middle East. Yet nobody abhorred political small talk more. When congressional liaison Frank Moore made arrangements for the president to woo a powerful Kentucky senator by having him greet a constituent who had painted a portrait of Carter using the distinctive medium of peanut butter, the president bristled: “Well, I gave you the time, and I see you’re going to waste it.”

A common thread in the oral histories was that the quickest way to get on Carter’s bad side was to present arguments about the political consequences of the choices before him. His job as he saw it was to enact the right policy, and voters would reward him accordingly.

A common thread in the oral histories was that the quickest way to get on Carter’s bad side was to present arguments about the political consequences of the choices before him. His job as he saw it was to enact the right policy, and voters would reward him accordingly.

The best manifestation of Carter’s style in operation was the Panama Canal treaties in 1977–78. Carter organized an extraordinary lobbying campaign on the merits of the initiative, including a highly successful effort with state politicians and interest groups to win congressional support for a policy with almost no native constituency. It was a tour-de-force of public pressure. By the account in Jonathan Alter’s book His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life, the return of control to the Panamanians avoided a major Central American war. But it also sparked high controversy domestically among those who saw it as a “giveaway.” This provided Governor Ronald Reagan, who at that moment was perilously close to has-been status, precisely the kind of hot-button issue he needed to energize a conservative base against Carter.

The presidency can be a brutal place, and it surely was for Carter. He found himself owning a host of intractable problems at a time when the institution was enfeebled. And the best policy fixes available to him did not respect the electoral calendar. When, for example, Carter appointed Paul Volcker to chair the Federal Reserve in 1979, he knew two things: (1) that Volcker could only be successful in bringing down inflation by imposing excruciatingly high interest rates and (2) that the benefits of that pain wouldn’t be experienced until after the next election. He named Volcker anyway.

Piled on top of these troubles was the hostage crisis, which Carter ruefully helped set in motion by conceding, reluctantly, to allow the ailing Shah of Iran into the United States for medical care. In his oral history, Carter likened this experience to the relentless specter of personal bankruptcy that haunted him once earlier in life.

“No matter what happened,” Carter recounted, “if it was a beautiful day or if my older son made all A’s on his report card or if Rosalynn was especially nice to me or something, underneath it was gnawing away because I owed $12,000 and didn’t know how I was going to pay it. . . . It was a gnawing away at your guts no matter what. . . . Well, that’s the way the hostage thing was for me for 14 months. No matter what else happened, it was always there.”

Jimmy Carter erred. But he did not flinch.

When an April 1980 rescue mission crashed in the Iranian desert, Carter surely knew that his chances for reelection had cratered too. But he quickly went on nationwide television to take full blame for the failure. “It was my decision to attempt the rescue operation,” Carter said. “It was my decision to cancel it when problems developed in the placement of our rescue team for a future rescue operation. The responsibility is fully my own.”

Jimmy Carter erred. But he did not flinch.