Electing the president: The people's power

A true national vote is an obvious reform but would be hard to achieve

The 2024 presidential election will mark the 200th anniversary of both a first and a last in the ongoing development of how Americans elect their chief executive. These anniversaries help illustrate our unusual presidential election system in which participatory democracy has been grafted onto institutions that were not necessarily designed to be small-d democratic.

Our unusual presidential election system grafts participatory democracy onto institutions that were not necessarily designed to be small-d democratic.

The 1824 election is the first election for which it is possible to tabulate a national popular vote for president, although not from every state. Before 1824, presidential electors were generally chosen by state legislatures.1 Over the course of the past two centuries, the franchise has been expanded, although battles remain about whether certain people should be excluded (e.g., convicted felons) and how easy it is to register and cast one’s vote. But the national popular vote does not actually matter in selecting the president—only the Electoral College does.

The 1824 election was the “last” where no candidate won the necessary majority of electoral votes to become president, forcing the House of Representatives to select the president. The House went with John Quincy Adams even though Andrew Jackson had won pluralities of both the electoral and popular votes. The House of Representatives endures as a backstop to select the president if no one wins an Electoral College majority; in this constitutional provision, each state (as opposed to each member) gets a single vote. It is hoped that 1824 will remain the last time this process is ever used, as confusion and crisis are likely if this obscure relic from a nondemocratic time must ever be used again.

The Democratic Party can trace its roots to Jackson, who came back to defeat Adams in 1828, and Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren; the Republican Party came later, in the 1850s.

The selection of the two major-party presidential nominees was, from the antebellum period through the 1960s, an insider-dominated affair. These conventions, packed with delegates selected by or loyal to party leaders, hashed out nominations.

The selection of the two major-party presidential nominees was, from the antebellum period through the 1960s, an insider-dominated affair.

Primaries emerged during the Progressive Era but did not come to dominate the delegate selection process until the 1970s, following Democratic Party changes prompted by the disastrous 1968 Democratic National Convention, when Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s nomination was never much in doubt despite winning only 2 percent of the vote in that year’s primaries. Republicans followed the Democrats’ changes, and the share of convention delegates selected in primaries rapidly increased. In 1968, both parties selected just a little more than one-third of their delegates in primaries; by 1976, that total was up to around 70 percent in both parties (with the Democratic total a little higher than the Republican total).2

The total would oscillate over time, but in 2016, the most recent competitive GOP nominating contest, 38 of the 50 states held primaries; in 2020, the most recent competitive Democratic nominating contest, 46 of the 50 did. 3 This evolution has also essentially eliminated the power of unbound or unpledged party leaders to participate as delegates, meaning that the delegates are almost all bound or pledged to state-level results. The Democrats created so-called superdelegates in advance of the 1984 election in order to provide roughly 15–20 percent of the delegate slots to party leaders who could vote as they pleased independent of the primary or caucus results. However, the party removed their power to vote on a competitive first-ballot convention vote in advance of the 2020 nominating contest (superdelegates would wield real power only if the convention went to a second ballot, which has not happened in either party since 1952). Republicans still have a handful of such “free agent” delegates in a few states, but they amount to only 3 percent of the total number of 2024’s delegates.4 Just like with the emergence of mass democracy being grafted onto the old Electoral College, so too has mass democracy been grafted onto the old party nominating conventions.

But just as Americans were gaining a greater ability to pick presidential nominees at the ballot box, their effective power in determining presidential general election winners would fade.

But just as Americans were gaining a greater ability to pick presidential nominees at the ballot box, their effective power in determining presidential general election winners would fade.

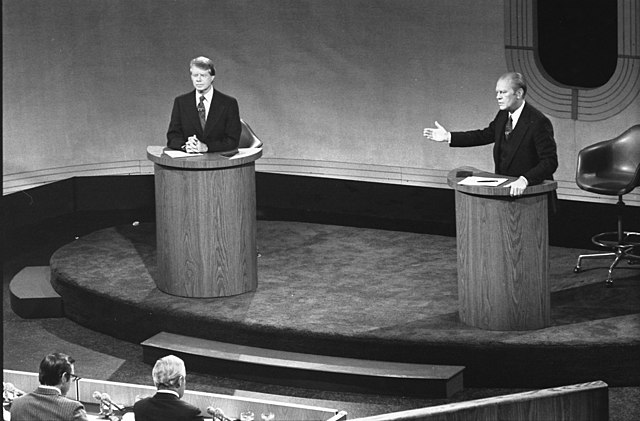

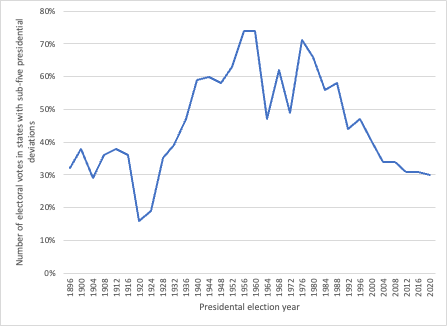

The 1976 election between Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford represented a recent high watermark in the number of electoral votes cast by states that voted reasonably close to the national popular vote. That year, states with about 70 percent of the total electoral votes voted within four points either way of the national two-party vote for president, which was 51 percent to 49 percent for Carter. That encompasses the range of states that voted for Carter with 55 percent of the vote to those that gave him only 47 percent of the vote, which we are defining here as competitive. So not only was the election close, but many individual states broadly reflected the national vote, meaning that a large number of voters lived in states that were competitive.

That competitive share has dwindled over the past half-century to the point at which, in 2020, only about 30 percent of the electoral votes came from states defined here as competitive, meaning that 70 percent of them came from places where the presidential outcome was not realistically in doubt. The historical trajectory from 1896 to 2020 is shown in figure 1.

The past half-century of presidential elections has seen a couple of arguably contradictory trends: an expansion of the voters’ ability to pick presidential nominees via primaries but also a contraction of their power to influence the general election, given the concentration of electoral power in just a portion of the nation’s states.

The past half-century of presidential elections has seen . . . an expansion of the voters’ ability to pick presidential nominees via primaries but also a contraction of their power to influence the general election, given the concentration of electoral power in just a portion of the nation’s states.

It is easy to blame the expansion of the voters’ power in primaries for the effective contraction of their power in general elections, but there is at least one key confounding factor. The close presidential races in years like 1960 and 1976, when many states and the national electorate were close and competitive, also reflected a time when the parties themselves were more ideologically mixed than they are today, with a strong conservative southern wing of the Democratic Party still present and a more moderate wing of the GOP in certain parts of the country.

The modern ideological sorting of the parties contributes to a sorted electorate in many states. It is not obvious that changing the way nominees are selected—perhaps by the parties reempowering elites in their nomination process—would lead to more broadly competitive national elections, although it would restore a “vetting” function to party elites in choosing nominees. However, it is easy to see strong opposition, particularly among the antiestablishment-dominated modern Republican Party, to turning back the clock on the democratization of presidential nominations.

The more obvious reform—so obvious and yet so hard to achieve—would be to do away with the Electoral College altogether and replace it with a true national vote for president. Just as other federal elected officials, House and Senate members, are elected by a single district, so too should the president, whose district is essentially the entire country. Formally adopting such a system would involve amending the Constitution, which would require a level of bipartisan buy-in that currently does not exist.

The more obvious reform—so obvious and yet so hard to achieve—would be to do away with the Electoral College altogether and replace it with a true national vote for president.

An end run around the Electoral College—an interstate compact that would bind 270 electoral votes’ worth of states to allocate its electors to the national popular vote winner, no matter how those states had actually voted—has made some progress over the years, winning support from 205 electoral votes’ worth of states.5 However, the signatories to the effort are entirely from Democratic states. Moreover, it is unclear whether the effort could get to 270 and, if it did, whether the compact would actually work in practice, particularly if a signatory state was controlled by a different party than the one that initially signed onto the effort or that won the state in the presidential election in question.

If the national popular vote compact ever did activate, it would be a familiar innovation—a majoritarian work-around grafted onto an ancient institution, the Electoral College, created at a time when mass democracy was not being practiced.

Endnotes

Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 207–8.

John S. Wooley, “Percentage of Democratic Party Convention Delegates Selected in Democratic Primaries,” American Presidency Project (n.d.), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/percentage-of-democratic-party-convention-delegates-selected-in-democratic-primaries; “Percentage of Republican Presidential Convention Delegates Selected in Primary Elections,” American Presidency Project (n.d.), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/data/percentage-of-republican-presidential-convention-delegates-selected-in-primary.

I calculated using “Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections,” https://uselectionatlas.org/.

“Presidential Primaries 2024: Republican Hard and Soft Count Delegate Summary,” The Green Papers, updated Aug. 29, 2023, https://www.thegreenpapers.com/P24/R-HS.phtml.

“Status of National Popular Vote Bill in Each State,” National Popular Vote (n.d.), https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/state-status.