"Joining the Revolution"

The uneasy collaboration between Lyndon Johnson and the civil rights movement

Adapted from Chapter Four of Rivalry and Reform, by Sidney M. Milkis and Daniel J. Tichenor

As early as 1965, it became clear that President Lyndon Johnson’s effort to become a leader of the civil rights movement suffered from his attempt to manage all the other responsibilities that the modern presidency pulls in its train. Johnson’s decision to expand America’s involvement in Vietnam, in particular, stemmed in part from his firm belief that nothing could be accomplished unless certain received commitments were steadfastly affirmed. However, this view unwittingly confirmed the view of civil rights activists that the presidency ultimately could not be trusted to further their cause or to embody their moral vision.

In the end, the Great Society revealed both the untapped potential for cooperation between the modern presidency and social movements and the inherent tensions between “high office” and insurgency that made such collaboration so difficult. Johnson’s announcement on March 31, 1968, that he would not seek or accept the nomination of his party for another term as president marked a failure to align himself and the powers of the modern executive with the carriers of a new politics, not only civil rights activists, but also consumer, environmental, and women’s rights advocates. The tasks of the modern presidency—the domestic and international responsibilities that constrained the “steward of the public welfare”—necessarily limited the extent to which Johnson could become a trusted leader of the social movements that arose during the 1960s. By 1968, Johnson, the self-fashioned agent of a political transformation as fundamental as any in history, had become a hated symbol of the status quo, forced into retirement lest he contribute further to the destruction of the liberal consensus. As he privately told Humphrey in the spring of 1968, “I could not be the rallying force to unite the country and meet the problems confronted by the nation . . . in the face of a contentious campaign and the negative attitudes towards [me] of the youth, Negroes, and academics.”

Despite his estrangement from the civil rights movement, Johnson’s approval ratings among black Americans remained consistently high throughout his presidency, signaling an important partisan realignment. In effect, civil rights and other key social organizations rivaled (and eventually supplanted) labor as the core constituency of the Democratic Party, accelerating the transformation of regional voting patterns advanced by the 1964 election. Indeed, the reforms achieved during Johnson’s presidency secured an important role for civil rights activists in a transformed Democratic Party. So much was made clear by the delegate fights that took place at the 1968 Democratic convention.

These battles were a sequel to the struggle over the seating of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) at the 1964 convention, when as part of the compromise that resolved that controversy, Johnson supported a reform that would give the national party power to reject state delegations that carried on discriminatory practices. When the regular Mississippi Democratic Party failed to “comply either with the spirit or letter” of the 1964 convention’s call prohibiting racial discrimination, an insurgent coalition calling itself the Loyal Democrats of Mississippi (LDM) challenged the regular state organization’s legitimacy before the credentials committee of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The LDM, composed of twenty-two whites and twenty-two African Americans, included many members of the 1964 insurgency, including Fannie Lou Hamer, who returned four years later with the support of labor unions, teachers, and the NAACP, which began putting public pressure on the DNC to uphold “the national party mandate of 1964” prior to the start of the convention. Just as the MFDP’s claim was infused with moral passion by Hamer, so the LDM’s appeal was elevated by one of its key spokesmen, Charles Evers, brother of the slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers. The regular Democratic Party in Mississippi, he argued at the credentials committee’s hearings, “has defied the national party itself. This group not only keeps Negroes out of it but it also keeps open minded whites out.”

The regular Mississippi Democrats, supported by southern delegations as well as DNC chairman John Bailey, sought to save their seats in another eleventh-hour compromise. Like Johnson in 1964, Bailey’s support for the deal resulted from the warnings of other southern delegations that they would abandon the Democratic ticket if Mississippi regulars were not seated. But there would be no compromise this time. Fortified by the antidiscrimination rule that Johnson sanctioned in 1964, the credentials committee voted overwhelmingly (85–9) to seat the biracial LDM. It was a verdict supported by the top two contenders for the party nomination: Humphrey, who had played a key role in resolving the MFDP controversy, and Senator Eugene McCarthy, the formidable antiwar candidate. Hamer, an official delegate at last, received a standing ovation from the convention as she took her seat.

The action taken in the Mississippi case was, according to many civil rights activists, a “monumental victory” in the fight against the lingering effects of Jim Crow. As the Chicago Daily Defender editorialized, the Mississippi activists’ challenge to the regular state delegation rested not just on their adherence to the 1964 mandate but was also a “determinative test of the depth to which the national Democratic Party [was] willing to commit itself on the question of racial integration in the rank and file.” The Democrats had given a clear demonstration that their national party had a basic belief in racial equality and that, if an existing state party was not willing to abide by that belief, the convention was prepared to grant official status to a new state party that would live by it. Before the end of the Chicago meeting, the convention gave one more demonstration of this maxim. Pushed by the McCarthy supporters, the convention provided for the sharing of the Georgia vote by rival groups led by Atlanta state representative Julian Bond and the segregationist forces of Governor Lester Maddox, although most of the “regulars” rejected the settlement and walked out—another sign of the ongoing transformation of partisanship instigated by the civil rights revolutions of the 1960s.

The Democratic National Convention’s seating of two integrated southern delegations appeared to vindicate the politically oriented and nonviolent approach that characterized the initial alliance between the White House and civil rights leaders. Yet the triumph of the insurgents in Mississippi and Georgia was part of a larger national offensive against the regular party organizations and the modern executive office. Fueled by the radicalization of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, this assault fractured the Democratic Party and gave rise to a new form of politics that channeled many of the ideas but not the tactics of the black power movement. As one African American delegate from Maryland expressed this strategy in the wake of the clashes between police and antiwar demonstrators at the Democratic gathering in Chicago, civil rights activists had to bore from within. “People are no longer willing to turn the other cheek as they did with Dr. King. The only way to avoid violent confrontations with the existing structure is to take our battles to the main-line. We must speak out through the electorate and elect those who, once in office, will confirm our rights.” John Lewis’s election to Congress in 1986 best revealed that this aspiration to join the disruptive potential of social movements and the mainstream electoral politics was not a chimera.

In the clip below President Johnson discusses the violence at the 1968 Democratic National Convention with Chicago Mayor William Daley

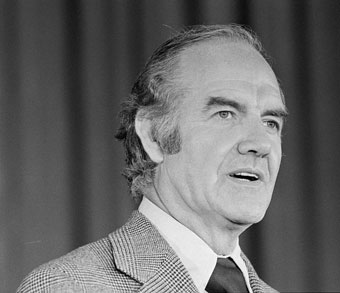

The antiwar movement, which was so closely aligned with the civil rights insurgency, also played a critical part in this transformation of politics. In a mark of its influence, Johnson saw the mantle of reform leadership pass to the likes of Eugene McCarthy, whose pioneering grassroots organization drove the president from the field in 1968, and George McGovern, the Democratic nominee for president in 1972. The “McGovern Democrats” who took control of the Democratic Party after the fractious 1968 presidential contest followed the progressive tradition of scorning party organizations—of desiring a direct relationship between presidential candidates and grassroots activists. In this respect, the expansion of presidential primaries and other changes in the nomination process initiated by the McGovern-Fraser reforms were the logical extension of the modern presidency and movement politics. But reformers rejected the concept of popular presidential leadership that prevailed during the Progressive and New Deal Eras.146 Viewing the president as the agent rather than the steward of the public welfare, new politics liberals embraced the general ideas current in the late 1960s that presidential politics and governance should be directed by social movements. This ideal represented a critical starting point for the joining of presidential leadership, social activism, and partisanship, which was further advanced by the collaboration between Ronald Reagan and the new Christian Right and came into full view during the presidencies of Barack Obama and Donald Trump.

Assuming the leadership of an embattled Democratic Party, McGovern’s insurgent presidential campaign was an electoral disaster. Nevertheless, unlike the ignominious retreat from post– Civil War reforms, the legislation conceived by the ephemeral alliance between Johnson and the civil rights movement led to the construction of a national administrative apparatus that had an enduring effect on American politics and governance.