Proving ground

How the December 1989 invasion of Panama shaped the Bush 41 foreign policy team

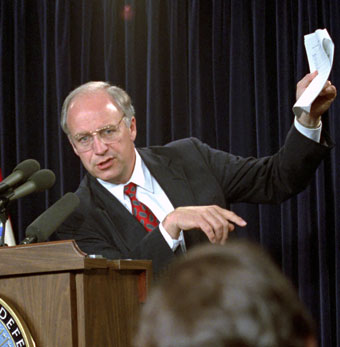

“Panama was a great training experience for us as an administration,” remembers then Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney in the Miller Center's George H. W. Bush Oral History Project. “We had the opportunity to have an objective, have to use force, coordinate with the Congress, deal with the public, all of those things that come with using the force. It was really the first time we’d done it as an administration, and we learned from that.”

“Nobody even remembers the Panama war. You don’t ever hear of it,” says Powell. “But I viewed it as the template of how we should do things.”

THE CONTEXT

Central America had been one of the focal points of the Reagan administration's foreign policy—and the source of its most embarrassing scandal: Iran-Contra, an attempt to circumvent U.S. law in order to support Nicaraguan rebel insurgents using funds secured by secretly selling arms to Iran. By 1987, Congress was holding very public hearings on the matter.

“Central America was front and center during that period of time in ways it hadn’t been before,” recalls Cheney. “I’d been a congressional observer in the first presidential election in El Salvador, when they held those.”

Panama was on the radar, but there wasn't much pressure to take action in Central America: “A significant body of opinion that said the U.S. did too much when we put 50 advisors in El Salvador.”

Throughout 1988, as Vice President Bush made his push for the presidency, the Reagan administration hoped to remove Noriega from power without a confrontation. Powell, Reagan's national security advisor at the time, remembers, “George Shultz and I were trying to ease Noriega out. We weren’t looking for a conflict; it just was time for him to leave.”

Vice President Bush staked out a more aggressive position but was unable to persuade President Reagan to chart a different course.

When Bush became president in January 1989, however, there was no appreciable change in Panama policy. “Send thousands of troops to topple a regime in Central America? It wasn’t an everyday conversation or discussion. There wasn’t anybody who was really arguing that at that point,” recalls Cheney.

In May, however, the administration replaced the commander of the U.S. Southern Command. “[Frederick] Woerner could find an excuse not to do anything in Panama," Cheney says. "We had continuing problems in relationships down there. So after a conversation with Brent [Scowcroft], I called Woerner in and relieved him. Then sent Max Thurman, who was getting ready to retire, who I think was a giant in the Army and had really done some phenomenally good things. I asked Max to go down and take on the assignment.”

Thurman began to prepare for the possibility of action against a background of growing tension and low-level conflict. The United States froze Panamanian assets, protested the harassment of U.S. military personnel, and complained about human rights violations. Noriega failed to respect the results of a May election, denying Guillermo Endara the presidency. American troops stationed in Panama conducted maneuvers, and the United States imposed additional economic sanctions.

THE COUP

On October 1, 1989, Powell became the youngest ever chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Two days later, Noriega thwarted a coup attempt, executing the perpetrators. For Cheney, the incident was evidence that the new administration, experienced as individuals, was not yet an effective team.

We were disorganized, out of place.

"We had gotten word that there was going to be a coup attempt. We scurried around on it. By the time, we weren’t even able to make a decision as an administration as to how we were going to respond to that.

“We were disorganized, out of place. I’m up running around in Gettysburg. General Powell has just been sworn in; he’s the brand-new chairman. I don’t know where the hell Baker was. We didn’t react well to it, and it bothered us a lot.

“One of the real problems you have with any new administration, even one as experienced as ours was—I mean, we weren’t a bunch of amateurs, we’d been around there before—it’s hard. You know, there is no training ground for senior civilian political leaders in an administration.”

The administration wouldn't let another opportunity to act pass by—and they wouldn't have to wait long.

THE “ACTION FORCING EVENT”

On Friday, December 15, the Panamanian General Assembly passed a resolution declaring that a state of war existed between the two nations. Thurman had been in charge for seven months, and a new plan—“Operation Just Cause”—was now in place. Powell remembers what happened next:

“The precipitating event takes place on that Saturday night, and one of our people is killed, some other people are abused, and some females are rudely dealt with, and it all came flooding into the Pentagon. Max and I are talking in the course of the evening, and the next morning, the president wants to see us about it, with recommendations about what to do.”

Powell gathered the chiefs at his home in Virginia and secured their unified commitment to the plan. Then he crossed the river to see Bush and Cheney in the residence at the White House. “The president asks some questions about it, and all the while he’s thinking it through. After he has analyzed it and asked a few questions and gotten the answers back from his diplomatic and political folks, he said, ‘Let's do it.’”

“There were two guys out there who seriously underestimated George Bush,” says Cheney. “One was Noriega and the other was Saddam Hussein.”

The invasion began on December 20, 1989. On January 3, Noriega surrendered to U.S. forces. By January 12, the operation was over.

Less than a year later, another former American ally would present an even more complicated challenge to the administration.

THE AFTERMATH

On August 2, 1990, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, drawing condemnation and diplomatic sanctions from the United States and other members of the United Nations Security Council.

We got to do it in Panama before we had to do it in Kuwait.

As the administration prepared plans to force the Iraqi army out, Cheney and other members of the team could rely on the lessons of Panama.

“It’s like anything else, if you’ve done it, you have a better feeling about how to do it," he says. "About the kinds of information you need, the kinds of decisions you have to make, the relationships among the principals in the operation, how the president likes to operate. . . . We obviously had no idea that a year later we’d be doing Desert Storm.”

For Powell, the action clarified his role and secured his place in the chain of command.

The only orders I could issue are those that the secretary had approved, and we were faithful to this.

“I had no authority to issue an order," Powell says. "The only orders I could issue are those that the secretary had approved, and we were faithful to this. I would not take anything up there that did not begin with the words, ‘The secretary of defense has directed.’ Only then would I sign it, as the releaser of the message, not as the guy authorizing it. The secretary of defense has directed every single operational order. Not administrative stuff, but if it’s sending troops into battle or to get ready for battle, it had to start with ‘The secretary of defense has directed,’ even though Cheney made it clear that he wanted everything to go through me.