From first general to declarer of wars

Presidents now have the ‘authority to wage war where and how they please’

The following is excerpted from Chapter 6 of The Living Presidency, by Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash, Copyright © 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved

Our commander in chief is a powerhouse. At beck and call are more than a million of the world’s finest warriors, an annual military budget of almost 700 billion dollars, and earth’s most destructive and sophisticated weaponry. Occupants of the Oval Office, from Harry Truman on, have gone on a military acquisition spree, securing for presidents the authority to wage war where and how they please. Meanwhile, Congress, though it retains vestiges of its authority to declare and direct war, is but a faint shadow of its 1789 version and poses little resistance to executive usurpations.

In no other realm have the humbling of Congress and the aggrandizement of the presidency been as comprehensive.

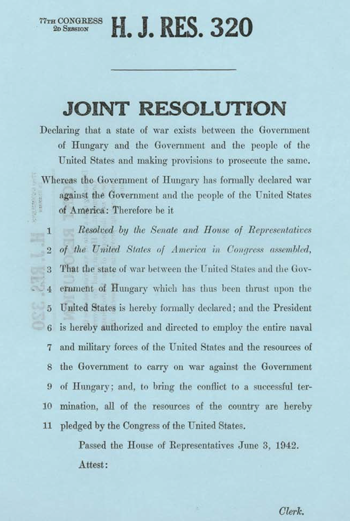

In no other realm have the humbling of Congress and the aggrandizement of the presidency been as comprehensive. Parts of the story are familiar. Others will be a revelation. As a people, we have forgotten what it means to declare war and the scope of congressional power over wars. For instance, many imagine that if Congress has not passed a formal declaration, it has not declared war. Likewise, many assume that commanders in chief simply must enjoy tremendous autonomy over the military or else they would not be genuine commanders. These modern notions of the power to declare war and of the commander in chief would astonish and dismay the Founders.

The Commander-in- Chief Clause has long mystified people. As Justice Robert Jackson noted in Youngstown more than fifty years ago, the clause has “given rise to some of the most persistent controversies in our constitutional history. Of course, [the clause’s words] imply something more than an empty title. But just what authority goes with the name has plagued presidential advisers who would not waive or narrow it by nonassertion yet cannot say where it begins or ends.” Needless to say, we have a major problem if the president’s legal advisers do not know where the commander in chief’s power begins or ends. Jackson’s observation was no ordinary critique. It was, in part, an admission that the clause baffled him. In his former life, Justice Jackson had been Franklin D. Roosevelt’s attorney general. As one might expect, Attorney General Jackson had read the seemingly nebulous clause expansively in order to favor his superior.

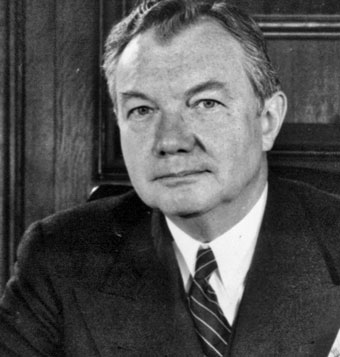

Truman further resolved to do whatever he thought necessary to triumph in his war, including seizing private property thousands of miles from Korean shores.

Justice Jackson made his veiled admission in a case about whether President Harry Truman could seize steel mills. The seizure was supposedly meant to ensure supplies for the Korean War. The president’s lawyers insisted that the commander in chief could do whatever was needed to prevail in that war. But to Jackson, and to several other justices, this was sheer chutzpah. You see, Truman had unilaterally thrust the United States into a terrible land war. Using that constitutionally irregular decision as a shaky foundation, Truman further resolved to do whatever he thought necessary to triumph in his war, including seizing private property thousands of miles from Korean shores. This was a particularly egregious form of legal bootstrapping.

Truman’s unilateralism serves as a microcosm of the modern era. In fact, his actions did much to usher in our current predicament, which is marked by a marginalization of congressional authority and a mushrooming of presidential power. Though Truman lost the steel seizure battle and his war ended in a stalemate, his successors have largely won the battle over the conduct of warfare and the scope of the Commander-in- Chief Clause. In particular, modern presidents assert constitutional authority to wage war, a right to ignore legislative regulation of the military, and autonomy in the conduct of war. While presidents face a more difficult time invading civil liberties during wartime, they have little difficulty invading Congress’s constitutional powers and ignoring Congress’s laws.

Congress is the true sustainer of wars that have aggrandized the presidency.

This vision of unchecked presidential powers to start and wage wars has received a significant boost from the most unlikely of sources: Congress. Since the Korean War, the United States has been in a state of perpetual military readiness because Congress has funded an enormous standing army, along with a massive navy, air force, and marine corps. This permanent and highly potent military apparatus is at the beck and call of every president, ready to wage war at the president’s discretion. While “[w]ar [may be] in fact the true nurse of executive aggrandizement,” as James Madison warned, Congress is the true sustainer of wars that have aggrandized the presidency.

Truman’s theory of war powers represented a sharp break with the Founding. The original Constitution had installed a belt, suspenders, and rope approach, with almost everything in it designed to both empower Congress and enfeeble the unitary executive. First, war could be waged only after Congress sanctioned it by law. The Constitution provides that Congress enjoys the power “[t]o declare war.” This included the power to start a war, for to “declare war” was, among other things, to decide to wage it. Moreover, the allocation of the declare-war power to Congress was universally understood to mean that presidents could not take the nation to war.

Second, under the original scheme, Congress had constitutional carte blanche over the armed forces, with the power to create, disband, and regulate almost every aspect of the military. Congress decided whether to have an army and a navy, the size of both, and here to station those forces. Relatedly, Congress could dictate the proper uses of the army, navy, and state militias, in peace and in war.

Though the president could command the army and navy, those directives had to conform to the standing laws.

Third, the commander in chief was subordinate to Congress. Though the president could command the army and navy, those directives had to conform to the standing laws. If Congress decreed that a militia could be stationed in one location, the president lacked the constitutional authority to deploy it elsewhere. If Congress dictated that the navy could attack only certain enemy ships, those ships were the only lawful targets. Commanders in chief were but the “first [meaning topmost] General and admiral,” as Alexander Hamilton put it. They certainly were not autonomous generalissimos because Congress could command the commander in chief.

Fourth, Congress had complete control over the Treasury and could draw the purse strings closed in order to halt a war or starve a military establishment that imperiled the government or civil liberties. Because many of the Framers thought a standing army posed a greater threat than a permanent navy, the Constitution expressly states that Congress cannot appropriate funds for the army beyond two years.

[Presidents] have managed to all but expunge the Declare War Clause from Article I.

Since Truman, presidents have remodeled the War Constitution. They have managed to all but expunge the Declare War Clause from Article I. Every copy of the Constitution still lists the clause, but it now has little consequence, in much the same way that after the Thirteenth Amendment emancipated millions of slaves, a clause about fugitive slaves no longer had any significance. Presidents have also grafted onto their office a parallel power to declare war. (Don’t bother reading the Constitution to find out whether this is sanctioned—it’s not.) And last, presidents have gradually acquired greater autonomy over the military, including the authority to disobey congressional laws related to the military and its use. In short, when it comes to waging war and control of the military, modern practices have layered such a thick, opaque gloss on the Constitution that one can barely make out its original features.