The struggle for civil rights

Following World War II, African Americans demanded equality before the law

The Age of Eisenhower was a time of racial turmoil. During World War II, black Americans played a valiant role both in home-front factories and in battle-tested units on the front lines in the fight against Fascism. In the years after the war, black Americans demanded in return for their sacrifices that they be given equality before the law. Their heroic mobilization around that bold demand would shape American politics for decades.

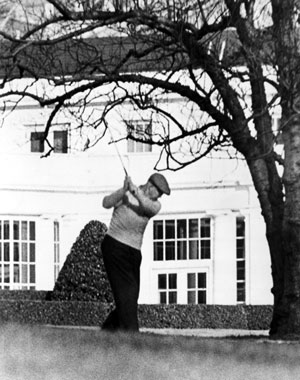

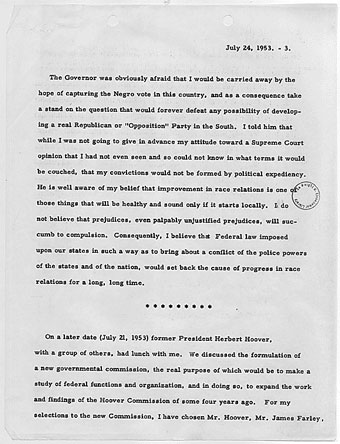

Dwight Eisenhower had little personal experience with or knowledge of black people. Ike grew up in rural Kansas with no black friends or teachers. He spent his career in the segregated U.S. Army; and his favorite place to unwind was Augusta National Golf Club, a bastion of white male privilege in the heart of the Old South.

During the 1952 election campaign, Eisenhower declared his “unalterable support of fairness and equality among all types of American citizens,” but quickly hedged: “I do not believe we can cure all the evils in men’s hearts by law” – a way of saying that the Federal government should not interfere with local customs. Where Federal authority did apply, however, as in Washington, D.C. and on military bases, Ike demanded rapid desegregation. He championed the desegregation of the nation’s capital in 1953 and he also followed through vigorously on Truman’s efforts to desegregate the armed forces.

On August 13 [1953], when he was putting pressure on the armed services to root out the last vestiges of segregation, Eisenhower announced the creation of the Committee on Government Contracts, a body designed to oversee nondiscrimination policies in the allocation of federal contracts. It marked a definite reversal for the president . . .

‘The Age of Eisenhower,’ chapter 9

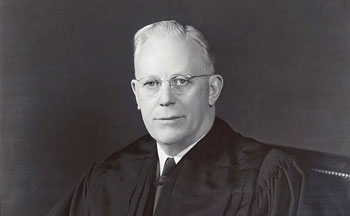

Even more significant, Eisenhower appointed Gov. Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on September 30, 1953. Earl Warren was a three-time winner of the California governorship and a former state attorney general. He had been the GOP vice-presidential candidate in 1948 and had a reputation as a moderate and a man of integrity. Warren had challenged Ike for the GOP presidential nomination in 1952, but this former political rivalry did not hurt his standing with Eisenhower who, after the general election, told Warren that he hoped to appoint him to the first vacancy on the Supreme Court.

The decision proved fateful, for the Court had just taken up Brown v Board of Education of Topeka. The plaintiffs wanted the Court to overturn the 1896 decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, that allowed states to segregate public facilities by race, provided that states made available equal facilities to black people. Attorney General Herbert Brownell and Earl Warren himself concluded that the “separate but equal” doctrine had perpetuated inequality among races and was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Thurgood Marshall, the chief counsel for the NAACP, masterfully made this argument before the Supreme Court and on May 17, 1954, the Court gave its unanimous opinion: Jim Crow must be banned from public schools.

The decision opened up many years of tension and conflict across the nation, as all-white schools grappled with the new legal demand to integrate. Some schools complied readily; many in the South refused, even closing public schools altogether to avoid “race mixing.” In March 1956, Southern members of Congress published “the Southern Manifesto,” which denounced the Supreme Court’s decision an abuse of power, described the Court as having destroyed in a stroke “the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races,” denounced “outside agitators” who wanted to bring “revolutionary changes,” and pledged to halt the implementation of school desegregation. The document was signed by 82 Representatives and 19 Senators—about one-fifth of the entire Congress. Opposition to equality for black Americans ran wide and deep.

On civil rights, it seemed, he planned to speak loudly and carry a small stick.

‘The Age of Eisenhower,’ chapter 9

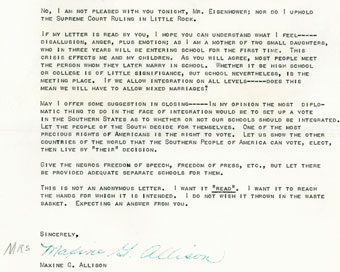

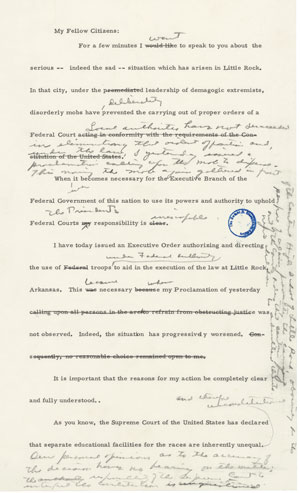

Eisenhower never wished to become a crusader on behalf of civil rights. The issue made him uncomfortable, and he often expressed his opinion privately that black activists wanted too much change, too quickly. But the president also refused to allow local school boards and state politicians to defy the rulings of the Supreme Court. When the school board in Little Rock, Arkansas, aided and abetted by segregationist Governor Orvall Faubus and the Arkansas National Guard, sought to bar black students from attending school in September 1957, Eisenhower moved decisively. He ordered units of the 101st Airborne to take command of the school and allow black students to enter the school building unmolested by angry mobs. He also federalized the Arkansas National Guard, thus placing those troops under his command. In an address to the nation on September 24, he expressed “sadness” for the decision to send troops to the city, but said “the President’s authority is inescapable.” Unless he carried out the orders of federal courts, “anarchy would result.”

Eisenhower avoided the moral questions at hand. He did not champion the need for equality and fairness in America, nor did he embrace the Brown decision. He went out of his way to praise the great majority of Southerners who “are of good will, united in their efforts to preserve and respect the law.”

Some contemporaries, and many later scholars, felt that Eisenhower should have done more to elevate the Little Rock issue to a moral plane, and express his solidarity with the moral cause of justice and equality for all. But Ike had a narrow view of the matter. His duty as president was to uphold federal court orders, no more and no less. In typical fashion, he found a middle way through a terribly difficult problem that would bedevil later presidents for many decades.