The Bank War

Democratic ideals and technocratic pragmatism clash

A Brief History of American Central Banking and Currency

Today, the issue of whether or not a central bank is of value to the United States is largely settled; since its creation in 1913, the Federal Reserve has set US monetary policy and acted as a bulwark against the normal boom and bust cycle of the American economy. No regulatory body is perfect, but on the whole, the US government and its citizens have agreed that we are better off with a central banking authority. This has not always been the case. In fact, the issues of currency, banking, and monetary regulation defined nearly a century of American politics.

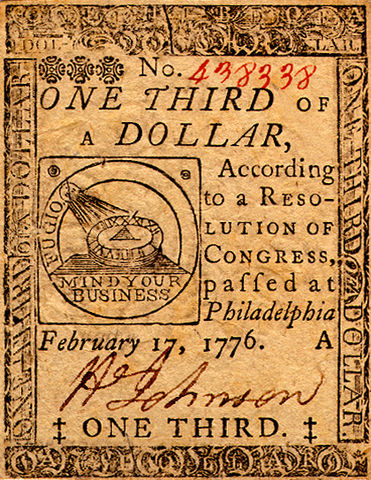

The history of American banking is inseparable from the history of its paper money. The dominant economic theory during the colonial period—mercantilism—was based upon the idea that trade was a zero-sum game; there was a maximum possible amount of trade in the world and a finite amount of hard metal coinage (specie) with which it could be conducted. In practice, this policy meant that specie was constantly flowing out of colonies and into Europe, forcing colonial American governments to begin experimenting with paper money and, in turn, runaway inflation. When the American Revolution began, the Continental Congress faced an even worse shortage of specie and again turned to wildly inflated paper currency. The new American government, limited as it was by the Articles of Confederation, could not levy taxes to pay off the massive debts it had incurred during the war and was left with a disastrous economy. Something had to change.

The new Constitution empowered Congress to levy taxes and, more critically to the issue of central banking, was vague enough to permit the establishment of a national bank. Alexander Hamilton, one of the architects of the Constitution and the first Secretary of the Treasury, was commissioned to draft a plan to improve the nation’s credit and ensure economic growth. He outlined a proposal which, among other controversial ideas, called for the establishment of a central bank. The bank would act as the Treasury Department’s agent, collecting revenues and disbursing payments. Most importantly, it would determine the quantity of paper money in economy and store US specie reserves. Hamilton believed that a such a bank, independent of direct control by the government, would regulate American credit and currency based on expertise rather than political will.

Congress approved the charter for the First Bank of the United States in 1791, and for twenty years the American economy generally prospered. But, by the end of the 1800s, the Federalist Party that supported the Bank had nearly disappeared, and its petition for a recharter was made to an unsympathetic Democratic-Republican Senate. The vote came down to a tie, and Vice President George Clinton broke it against the Bank. By 1811, the First Bank of the United States had sold off its branches and ceased to exist.

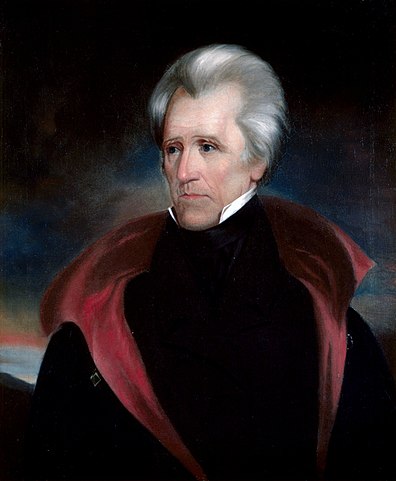

The Bank could not have closed at a worse time. The next year’s War of 1812 bankrupted the US Treasury, and the same state banks that opponents of the Bank had claimed were perfectly capable of managing American finance turned out to be incredibly unreliable. Popular opinion again swung towards support of a central bank, and the Second Bank of the United States was born out of the same Madison administration that had killed the First. The new Bank almost immediately faced serious challenges, including a Supreme Court battle. Only a few years after its opening, the United States experienced its first peacetime economic crash: the Panic of 1819. The Bank responded to the crisis in ways that seemed only to make the depression worse, reigniting public resentment against it. After all, wasn’t the Bank supposed to prevent such crises? The Panic of 1819 and the Bank's lackluster response sowed the seeds of its destruction. Anger towards the Bank was once again on the rise, and one man knew how to use it: Andrew Jackson.

The General and The Banker

With the Panic of 1819, Jackson was quick to blame the Bank, and he was not alone. The Bank’s failed response to the panic sparked a major reshuffling in leadership and propelled a younger board member, Nicholas Biddle, to the presidency of the Bank. Though he would quickly restore order to the Bank and bring stability to American finance, he also would also be the Bank’s last president and the man who would lead it into its fatal confrontation with Jackson.

“Old Hickory,” now a war hero and natural populist, hoped to leverage his popularity for a bid for the presidency in 1824. Despite winning the largest percent of the popular vote in the general election, Jackson lost when the vote went to the House of Representatives, in part due to rival candidate and perpetual nemesis Henry Clay throwing his support behind John Quincy Adams. Jackson and his supporters slammed the House vote as a “corrupt bargain,” a product of closed-door deals between corrupt politicians and the elites who owned them to deny the people the president they wanted. The Bank of the United States, not to be left out, was blamed for bankrolling Jackson's opposition. (Ironically, Biddle himself had voted for Jackson).

The bitterness that followed the election of 1824 closed the so-called “Era of Good Feelings” that had defined American politics in the years after the War of 1812. Having outlasted the Federalists, the Democratic Republicans enjoyed total domination of American politics for more than a decade, but this political consensus was lost in the growing rift between Jackson’s populist brand and the old party establishment. By the election of 1828, the party had begun to split between the Jacksonian Democrats and the Anti-Jacksonian National Republicans, but it was not yet a clean break. Jackson won the 1828 election with 56 percent of the popular vote and a solid electoral majority. As a gesture of reconciliation to the splintering Republicans, Jackson invited many Republican-leaning politicians into his cabinet, and they acted as a bulwark against his plans to dismantle the Bank. Chief among these Bank-friendly voices was Jackson’s own vice president, John C. Calhoun, who had championed the Bank's rebirth in the Senate only a decade before.

Unfortunately for the Bank, this uneasy truce between Democratic factions could not last. Jackson quickly tired of his contrarian cabinet and turned instead to his friends, a group known as the “kitchen cabinet.”

Of course, Jackson did have legitimate concerns about the Bank—congressmen openly received generous loans and stipends from the Bank, a practice Jackson detested as blatant corruption. Furthermore, he believed that the Bank entrenched economic power and policy among the northern elite, who neither knew nor cared about the economic needs of common Americans. Nonetheless, Biddle never gave up trying to bring Jackson around, scheduling meeting after unsuccessful meeting with the president. Fortunately for the survival of the Bank, Jackson rarely had time during his first four years to think about the Bank, as he was too busy dealing with the endless crises within his White House. Most important for the Bank was the Eaton affair, a personal spat between members of the cabinet that ultimately consumed nearly two years of the administration. Jackson dealt with the problem by dismissing those members of the cabinet who disagreed with him, including many advocates for the Bank, and replacing them with men whose primary loyalties were to Jackson himself. The nullification crisis gave Jackson the pretext he needed to replace his vice president and advocate for the Bank, John Calhoun, with Martin Van Buren.

Van Buren was personally neutral on the Bank issue; he both recognized its value and agreed that it had problems. However, what was most important to Van Buren was his political future, and it was inexorably tied to Jackson’s success and popularity, Bank or no Bank. If the Bank were to become the central issue of the 1832 presidential campaign, there would be no doubt as to which side Van Buren would support.

The Battle for Recharter

As the election approached, Biddle found himself and the Bank in an increasingly perilous position. The Bank’s charter was due to expire in 1836, but Biddle could submit a petition for recharter before that date if he believed it more likely to pass. Jackson warned Biddle that he would veto any bill to recharter the Bank that came across his desk before the election, fearing that the issue would cost him votes, but Biddle believed that the electoral pressures of the election were the only leverage he had to force Jackson to sign a recharter.

Championing this view was Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, Jackson’s opponent in the election. Clay’s support for the Bank of the United States was almost entirely predicated on the success of his presidential campaign. This forced Biddle into a difficult position. Clay and his allies were the only powerful supporters the Bank had left; if Biddle rejected their advice and delayed the recharter, he risked losing the only support he had left in Congress. What Biddle did not know was that Clay’s support for the Bank recharter was secretly based on the belief that Jackson would veto it. This would kill the Bank, the exact outcome Biddle was trying to avoid, but Clay hoped it would arouse public sentiment against Jackson and cost him the election. Clay and his supporters assured Biddle that Congress would have such an overwhelming majority of support for the bill that Jackson would not dare veto it.

Biddle submitted his bid to recharter the Bank of the United States to Congress on January 6, 1832, with concessions he hoped would placate the president and his supporters. Jackson was furious, seeing Biddle’s political gamble as proof that the Bank’s influence was being misused to influence American politics. There would be no compromise; from this point forward, destroying the Bank became Jackson’s single minded goal.

Despite his opposition, the Senate successfully passed the recharter bill with a vote of 28 to 20 and then the House passed it by 107 to 85. Even in the face of Jackson’s crusade against the Bank, a broad base of support remained among northern and mid-Atlantic congressmen. However, Jackson loyalists were so vocal in their opposition to the Bank that even Biddle expected Jackson to veto the bill. Nevertheless, he and Clay were still optimistic that the majority of the American public supported the Bank. If he dared to veto the recharter, the people would vote him out of office, and Clay would resurrect it. Clay even remarked that “Should Jackson veto it, I will veto him,” but neither were truly prepared for the counterattack Jackson had in mind.

Jackson's Veto

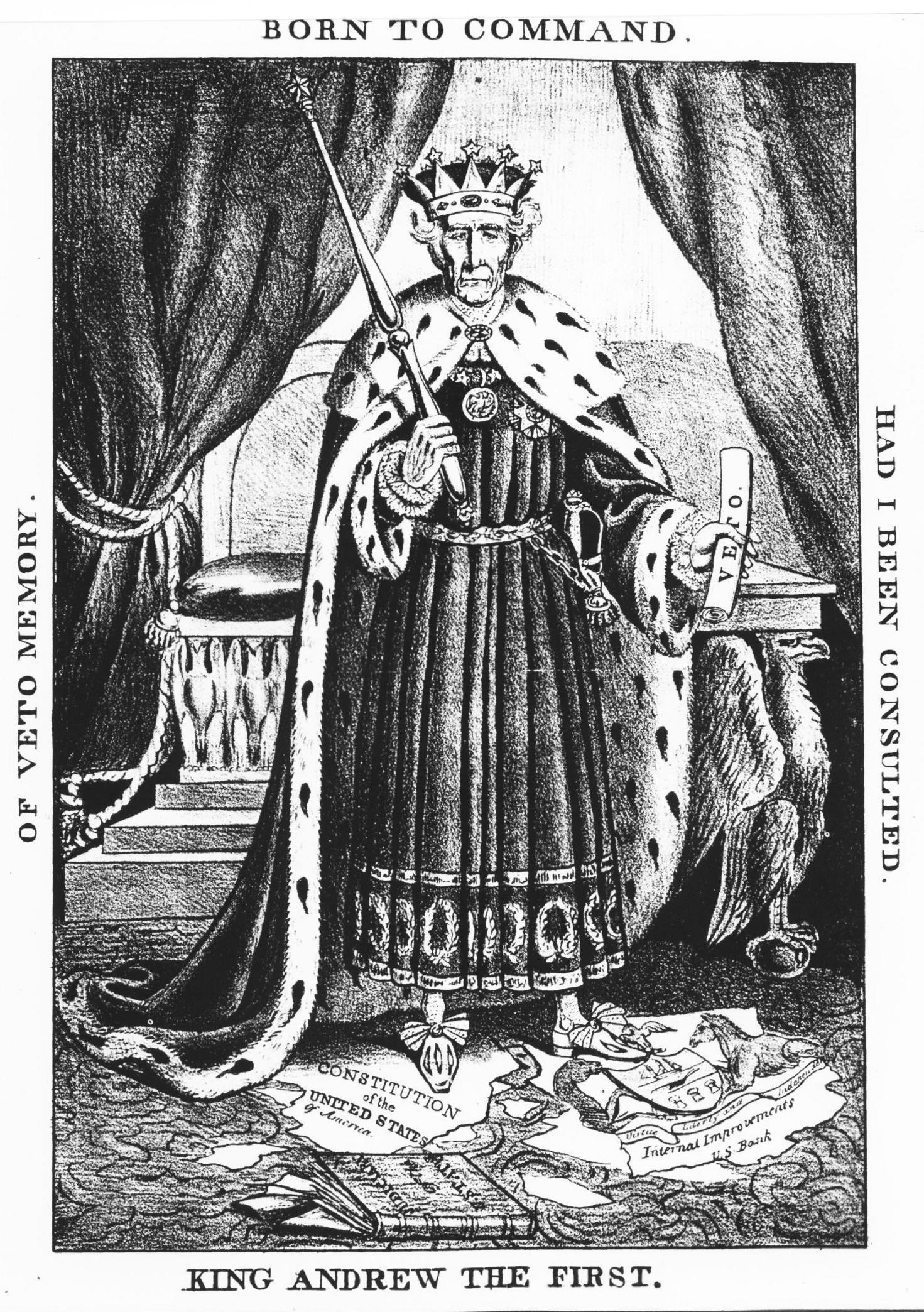

Jackson submitted a breathtaking veto message to Congress that stunned everyone who read it and redefined American politics. Previous presidents would only veto a bill they believed to be unconstitutional. Jackson’s veto deemed the Bank unconstitutional out of hand (flagrantly ignoring Supreme Court precedent), but he also cited political, social, and economic reasons for the veto, establishing the idea that a president could veto a bill they disagreed with even if it was constitutional.

Jackson also outlined a radically expanded vision of executive power, arguing that the Executive had explicit legislative powers and judicial powers. Finally, Jackson closed the veto with an appeal to ideals of economic equality and meritocracy in government, championing the rights of the common man and explicitly calling for his supporters to overthrow the politically elite, embodied in the Bank. The veto was perfect political propaganda—Democratic papers took the president’s message and spread it across the country, where readers seized upon it as a rallying cry for Jackson's reelection. The Bank’s survival hinged on Jackson losing in 1832.

1832 Election and Aftermath

Thanks in large part to Jackson’s veto, the Bank became the primary issue of the campaign, which put Clay at a disadvantage. The veto had squarely established Jackson in the minds of voters as the champion of the people, and despite Clay’s reputation as an orator, none of his speeches or writings “stuck” in the same way that Jackson’s did. Clay and his supporters painted Jackson as a dictator, unconstitutionally overstepping his power and destabilizing the nation’s economy, while Jackson and his supporters doubled down against the Bank, accusing it of bankrolling the Republican opposition.

In the end, Jackson won with 54 percent of the popular vote compared to Clay’s 38 percent, a victory which at last doomed the Bank. Jackson had taken the risk of making the Bank issue a litmus test in the Democratic Party, forcing voters to choose between him or the Bank, and he had clearly won. The consequences of this were unmistakable: the single-party dominance of the Democratic Republicans was over. Jackson’s vendetta against the Bank crystallized the opposition against him into a new party: the Whigs.

The economic consequences of the Bank’s dissolution were severe as well. The process of removing the federal government’s deposits from the Bank was disastrous, and competition between the “pet” state banks who took on the responsibilities of the dying Bank reignited the problems of exchange rates and inflation that had plagued American money before the Bank’s reestablishment. The last stockholder meeting for the Bank of the United States took place on February 19, 1836, and was quickly followed by the most severe economic depression in American history: the Panic of 1837. The Jacksonian standard of unregulated monetary policy would drag the American economy down for decades until at last, after countless preventable recessions, the Federal Reserve was established in 1913.