The Diem coup in Vietnam

What did the U.S. know about the November 1, 1963, assassination of South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem?

The U.S. government saw South Vietnam's autocratic ruler, Ngo Dinh Diem, as a bulwark against Communism. But Diem was far from an ideal partner: Suspicious of anyone but his immediate family, he often frustrated American policy makers. But his success dealing with internal threats gave many hope that he would prove to be a reliable ally, so the United States invested time and money in supporting his regime.

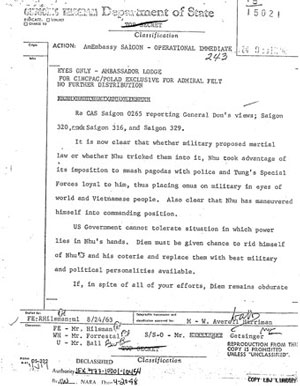

By 1963, however, the Kennedy administration faced a dilemma. After government forces cracked down on Buddhist monks that spring, Kennedy pressed Diem for reforms. Instead, Diem imposed martial law, and special forces directed by his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, launched raids against Buddhist pagodas. When rumors of a possible coup began to spread in August, many in the administration wondered whether the United States should acquiesce, or indeed support the plotters. Others dissented, seeing the regime, with all its faults, as the best path to success against the southern Vietnamese Communists—derisively labeled the Viet Cong—who were supported and directed by the North Vietnamese. Inside South Vietnam, those seeking to overthrow the regime contacted US officials to ensure continued American support.

In this August 26, 1963, conversation, the president discusses Diem and Nhu with senior national security officials.

Energy for the coup fizzled in late August, and the Kennedy administration resigned itself to working with Diem, pressuring him to make a series of political, economic, military, and social reforms that were designed to improve the counterinsurgency effort. But by late October, President Kennedy was again grappling with the possibility of a coup and what the United States should do about it. His advisors were divided. At a late afternoon meeting on October 29, Kennedy heard several opinions, clearly summarized in a memorandum of the conversation.

Secretary of State Dean Rusk suggested, "We should caution the generals that they must have the situation in hand before they launch a coup."

"Secretary McNamara," recorded the memo, "asked who of our officials in Saigon are in charge of the coup planning."

Attorney General Robert Kennedy expressed his doubts about breaking with Diem:

Averell Harriman, undersecretary of state for political affairs, "said it was clear that in Vietnam there was less and less enthusiasm for Diem. We cannot predict that the rebel generals can overthrow the Diem government, but Diem cannot carry the country to victory over the Viet Cong. With the passage of time, our objectives in Vietnam will become more and more difficult to achieve with Diem in control."

On November 1, those evaluations became moot as a group of Vietnamese army officers, led by General Duong Van Minh, assassinated Diem and Nhu. On the morning of November 2, McGeorge Bundy read reports of the coup to the president.

On November 4, Kennedy recorded his thoughts on the Diem coup into a Dictabelt (complete with punctuation).

[This recording has been edited to remove an impromptu visit from the president's children, John Jr. and Caroline.]

Eighteen days later, the US president himself would be felled by an assassin's bullet on the streets of Dallas.