‘I did not get off the car’

In 1854, a Black woman championed the end to segregated public transportation in New York City. A future president helped her.

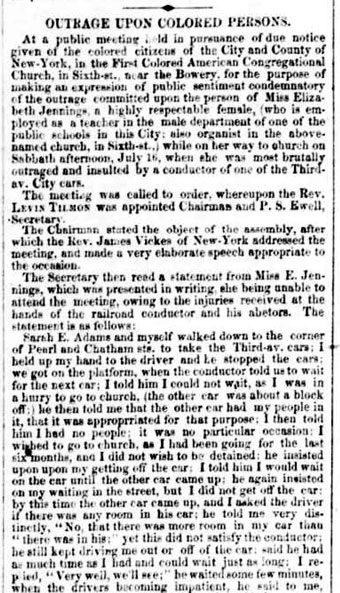

Elizabeth Jennings’s first-person account appeared in the anti-slavery newspaper The New York Daily Tribune on June 19, 1854. Three days before, this 24-year-old schoolteacher on her way to church had boarded the Third Avenue Railroad at the corner of Pearl and Chatham streets in New York City. The conductor told her to wait for the next car, because it would be accepting Black riders.

Jennings, an African American encountering segregation in the country’s largest city, refused. What ensued was a physical and legal battle in which another 24-year-old, Chester A. Arthur, would play an important role.

At first, Jennings argued with the conductor. “I then told him ‘I have no people . . . I wished to go to church,” she wrote in the Tribune account.

He refused to move the streetcar and said he “had as much time as I had and could wait just as long.” She replied, “Very well. We’ll see.”

Finally, the conductor appeared to relent, saying she could ride the car but would have to disembark if any white passengers objected. This was not good enough for Jennings, who demanded she not be subjected to either his authority or the whims of white citizens: “I…told him I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York…and that he was a good-for-nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons on their way to church.”

I then told him ‘I have no people . . . I wished to go to church.’

The conductor grabbed Jennings and tried to force her off. She grabbed a window, then the conductor’s coat. The conductor enlisted the help of the streetcar driver, who fastened the horses and helped drag the young woman to “the bottom of the platform, so that my feet hung one way and my head the other, nearly on the ground. I screamed murder with all my voice.”

Still, Jennings returned to the car, and the conductor ordered the driver to proceed to the police station, where an officer helped remove Jennings as he “tauntingly told me to get redress if I could.”

With the help of a future president, she could.

Chester Arthur, son of an abolitionist preacher and a new partner in the law firm of Culver, Parker & Arthur, had passed the bar only two months before. His firm was already involved in the case of Lemmon v. People of New York, trying to free seven enslaved Americans who had been placed in jail as their owner attempted to ship them from Virginia to Texas. It was unsurprising, then, that the tight-knit African American community of New York hired the future president and his firm to work for them on behalf of Jennings.

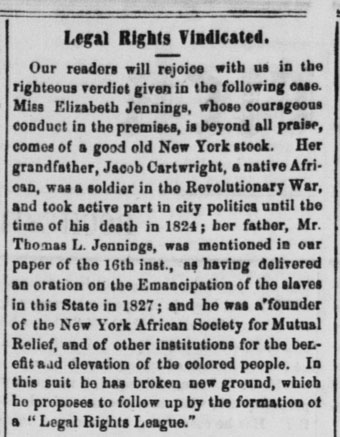

Jennings’s account received widespread publicity among African American New Yorkers and their supporters. Her father, Thomas L. Jennings, was a prominent tailor and community leader who helped found the famous Abyssinian Baptist Church. Her grandfather Jacob Cartwright was, as Frederick Douglass’ Paper noted, “a native African, a soldier in the Revolutionary war, and took active part in city politics until the time of his death.” Though slavery in the state had ended in 1827, Black citizens were determined to advance their rights, and to end slavery elsewhere. The Jennings family was at the forefront of the effort.

Related: “Biography of Thomas Jennings, First African American Patent Holder” from ThoughtCo

Arthur was soon in front of New York State Judge William Rockwell in a Brooklyn Court. Rockwell instructed the all-white, all-male jury that “under the law, colored persons, if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the right to ride the streetcars” and “could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence.”

On March 2, 1855, Douglass’ Paper reported the verdict: Jennings would be awarded $250 (less than the $500 for which she had asked). And when other New York streetcar companies failed to immediately integrate, Thomas Jennings’ founded the Legal Rights Association to challenge them. By the end of 1861 the entire system had been desegregated.

Arthur went on to win the Lemmon case in front of the New York State Supreme Court in 1860, but the victory came in the shadow of the Dred Scott decision and looming Civil War. During the war, Arthur rose to the rank of brigadier general and began to cultivate political connections that would leave him as James Garfield’s vice president. When Garfield was assassinated, Arthur became the 21st president of the United States.

Love of the beautiful will be instilled in these youthful minds.

Elizabeth Jennings continued to teach, married Charles Graham, and bore a son named Thomas, who died when he was one. Following the death of her husband, she founded New York City’s first kindergarten for Black children. “Love of the beautiful,” said a contemporary account of the school, “will be instilled in these youthful minds.” Elizabeth Jennings Graham died in 1901, 15 years after Chester Arthur.