The Tonkin Gulf Resolution

August 7, 1964: The passage of the Tonkin Gulf resolution was a pivotal moment in the escalation of the Vietnam War

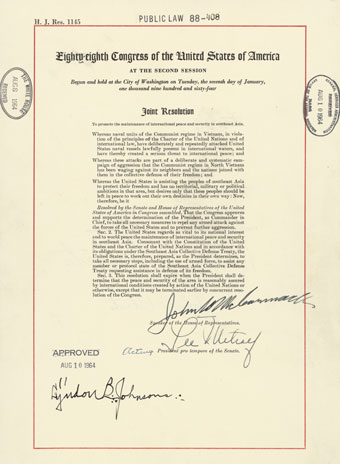

In August 1964, Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf resolution—or Southeast Asia Resolution, as it is officially known—the congressional decree that gave President Lyndon Johnson a broad mandate to wage war in Vietnam. Its passage was a pivotal moment in the war and arguably the tipping point for the disaster that followed. The resolution, passed by Congress on August 7, 1964, and signed into law on August 10, capped a series of events that remain controversial.

On August 4, two American destroyers, the USS Maddox and C. Turner Joy, reported being attacked by North Vietnamese military units in the Gulf of Tonkin, off the coast of central and North Vietnam. (The Maddox had reported similar action on August 2.) Characterizing the attacks as “unprovoked,” President Johnson ordered retaliatory strikes against North Vietnam and asked Congress to sanction any further action he might take to deter Communist aggression in Southeast Asia. Believing the administration’s account of these events, legislators acted swiftly, giving Johnson a virtual “blank check” to use US military force in Vietnam.

As frustratingly incomplete and often contradictory reports flowed into Washington, several high-ranking military and civilian officials became suspicious of the August 4 incident and began to question whether the attack was real or imagined. By the time that Johnson signed the Tonkin Gulf resolution on August 10, several senior officials—and probably the president himself—had concluded that the attack of August 4 had likely not occurred.

August 3, 1964

As news of the August 2 attack by a North Vietnamese PT boat on the Maddox reached Washington, administration officials publicly characterized the incident as unprovoked aggression. Privately, however, President Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara conceded that US covert operations in the Gulf of Tonkin had probably provoked the North Vietnamese.

Facing pressure on the right for a large-scale military response and from the left for disengagement, and not wanting to be forced down either path, Johnson used key bits of information to influence the political debate. To the most vocal critics on the right calling for a forceful retaliation, Johnson and his senior advisors quietly sent word that US covert operations in the region had probably provoked the North Vietnamese attacks. In public, however, the administration vehemently denied such claims and went to considerable lengths to discredit them, maintaining the official line that the attacks were unprovoked.

[transcript here.]

August 4, 1964

As real-time information flowed in to the Pentagon from the Maddox and Turner Joy, the story became more and more confused.

Admiral US Grant "Oley" Sharp, commander in chief, US Pacific Command, fed reports to Washington as soon as he received them. In this phone call, Sharp briefed Air Force Lt. General David Burchinal of the Joint Chiefs of Staff on the latest information he was receiving. This call was recorded at the National Military Command Center (NMCC) at the Pentagon. It is one of several related NMCC recordings released by the LBJ Library in June 2002.

[Chart originally prepared for The United States Navy and the Vietnam Conflict, Volume II: From Military Assistance to Combat 1959-1965, published in 1986 by the Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington D.C. (USA), page 423.]

August 6, 1964

Having spent the morning testifying to congressional committees, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara updated President Johnson about the mood on Capitol Hill regarding the Tonkin Gulf resolution. Despite a few dissenting voices on both sides of the aisle, McNamara reported that congressional support for the measure was strong.

[transcript here]

Election-year politics complicated the administration's response. While criticism from the likes of Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater was expected, Johnson was forced to contend with a renegade voice much closer to the White House.

President Johnson, McNamara, and Secretary of State Dean Rusk were all trying to convince Congress and the American public that the North Vietnamese attacks were unprovoked, but Hubert Humphrey, Johnson's presumed running mate in the upcoming election, broke with the administration line and revealed the classified, covert role that the United States had been playing to support South Vietnamese sabotage raids against North Vietnam in the Tonkin Gulf.

[transcript here]

They need not have worried. The following day, August 7, the Tonkin Gulf resolution passed Congress; Johnson signed it on August 10. The stage was now set for the "wider war" Johnson had said he would not seek.

Nearly six years later, on June 24, 1970, long after Johnson's presidency had become another casualty of the Vietnam War, the US Senate rescinded the Tonkin Gulf resolution. "The vote may have marked a turning point in the increasingly acerbic bickering in the Senate over the war," said the New York Times the following day. The Nixon administration was unperturbed, saying it was not relying on the resolution to authorize its policies in Vietnam.

*Adapted from a Miller Center article written by David Coleman and Marc Selverstone.