The turning point: 1968

One of the most eventful years in American history began with the Tet offensive in Vietnam and ended with the election of Richard Nixon

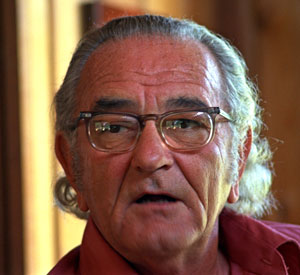

It was February 5, 1968, and Washington Star reporter Jack Horner had an angry President Lyndon Johnson on the phone. Johnson liked Horner and was willing to talk to him without being quoted, but he couldn't contain his frustration with the press.

"On this South Vietnamese thing," Johnson said, his voice rising, "we think we've killed 20,000. We think we've lost 400, . . . [I]t is a major, dramatic victory. And I think, what woulda happened if I'd lost 20,000 and they'd lost 400?"

Three and a half minutes later, the president hung up. The rest of the year wouldn't get any easier.

TET

Johnson was speaking of a massive Communist offensive, which began with the onset of Tet—the Vietnamese new year celebration—during the early morning hours of January 31. North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers and guerilla fighters of the People's Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), known to Americans as the Viet Cong, mounted a series of coordinated attacks in urban centers across the South in an attempt to provoke a "general uprising," permanently destabilizing the Saigon government and demoralizing US forces.

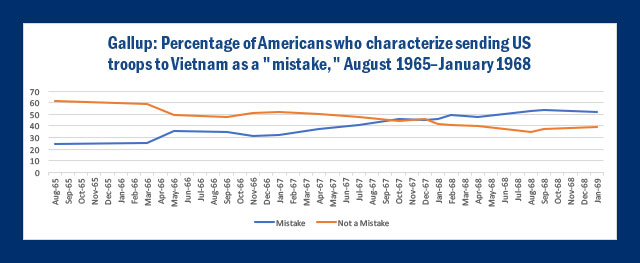

Militarily, the attack failed. It generated chaos but no uprising. The Communist NVA and PLAF took heavy losses. Both American and South Vietnamese troops performed well. But in the United States, Americans were largely shocked. The images on their television screens didn't match the narrative they'd been hearing.

And the questions they were asking were difficult to answer. If the United States was on the verge of winning the war, as government and military officials had told the country in the closing months of 1967, why were its troops beating back guerillas from inside the US embassy compound in Saigon? Why were its soldiers in the fight of their lives at Khe Sanh, a Marine combat base near the demilitarized zone separating North from South Vietnam? Why was there a desperate struggle raging at the ancient city of Hué, an engagement that would last 25 days before the Communists were forced to retreat?

The president's first worry was Khe Sanh. The NVA launched an attack on the Marine base on January 21, in advance of the main Tet actions, largely to draw US forces away from the urban centers. On January 22, Johnson talked with Robert McNamara, his secretary of defense, about the assault—and about coverage in the Washington Post.

On January 31, when the more widespread Tet attacks were well underway, Johnson asked for an evaluation from McNamara, who told the commander in chief that the North Vietnamese were stronger than previously thought; they would be defeated militarily, but they would also gain in the "propaganda" war. The president again expressed concern about how to shape the narrative about the war in an election year.

THE USS PUEBLO

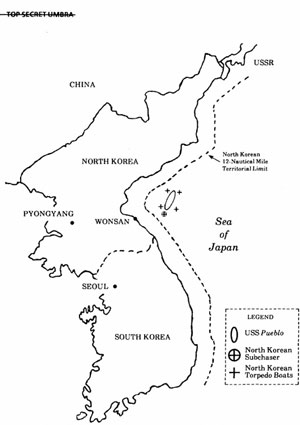

The latest challenge in Vietnam wasn't the only problem on the president's mind. On January 23, and with the attacks on Saigon and other cities yet to begin—the captain and crew of the USS Pueblo were captured by the Communist forces of North Korea. According to US intelligence, the Pueblo had been conducting operations 16 miles from the coast of North Korea in international waters. The North Koreans asserted that the vessel had violated their territory. Wary of the potential for another major conflict, Johnson ordered a military build-up in the area but resisted any direct action. As tensions mounted, he discussed efforts to free the men first with McNamara and then with Arthur Goldberg, the US ambassador to the United Nations. The sailors remained in captivity for 11 months until their release.

"I SHALL NOT SEEK . . . "

The president now faced the question of what to do next in Vietnam. General William Westmoreland, commander of US forces, requested an additional 200,000 men to follow up what he viewed as a successful performance during Tet. But the country, and Johnson, were growing skeptical. With more than half a million men already committed, and the Communists still a potent force, how many more US soldiers would it really take to win the war? Secretary McNamara had already suggested freezing troop levels and instituting a bombing halt, recommendations that put him in conflict with military leaders and the president, and led to his planned departure at the end of February. A task force charged with reviewing Vietnam policy recommended the president approve a little more than one-tenth of Westmoreland's request: 22,000 men. In the end, Johnson approved just 13,500.

Johnson faced economic difficulties as well. He wanted to finance the war without putting spending for his Great Society programs on the chopping block. Nor did he want to increase taxes. But federal borrowing in a growing economy fueled inflation and added to an overall balance-of-payments deficit in the US economy, weakening the dollar. The pressures became a certifiable crisis when the need for gold to back the currency (the US is no longer on the gold standard) ran up against huge worldwide demand for the metal, leading to massive financial losses for the US government.

There were also political considerations looming in an election year. As the country and Congress continued to question the war, Senator Eugene McCarthy (D-MN) agreed to mount an intra-party challenge to Johnson as an anti-war candidate. In the March 12 New Hampshire primary, McCarthy received a shocking 42 percent of the vote to LBJ's 50 percent. Senator Robert Kennedy (D-NY), a frequent Johnson antagonist, then entered the race, making it abundantly clear that the president would not enjoy an incumbent's traditionally smooth road to the Democratic nomination, let alone another landslide victory in the general election November.

After assessing these three factors—recent military success, growing public skepticism, and a fraught political environment—Johnson made a decision, which he announced to the nation in a prime-time speech on March 31. He would unilaterally scale back bombing of North Vietnam. He would continue to seek peace in Southeast Asia. But he would not seek another term as president, announcing his decision as follows:

"I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office—the presidency of your country.

"Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president."

A palpably relieved president discussed the surprise announcement with the Republican governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller.

MLK AND RFK: VIOLENCE AT HOME

Any relief Americans might have felt at the president's announcement disappeared four days later. Escaped felon James Earl Ray assassinated one of the nation's most revered figures, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a man with whom Johnson had shared many hours both in person and on the phone since early in his presidency. Anger, protest, and violence erupted in cities across the United States following the death of the civil rights icon.

King assassination phone calls

After calling King's widow, Coretta Scott King (no recording exists of the call), Johnson talked to Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen about the tragedy and the potential for unrest—and violence.

That fear became a reality in several cities, including the nation's capital and Chicago. On April 6 Johnson talked to Senator John Stennis (D-MS) about unrest in Washington.

Later that day, the president heard from Chicago mayor Richard Daley, who requested federal help and at least 3,000 troops to quell the violence. Following his call with Daley, Johnson discussed the process for sending in troops with Ramsey Clark, the attorney general. On April 8, he got an update on events in the District from aide Cyrus Vance, who had dealt with riots in Detroit in 1967.

Two months later, another American leader was gone. Robert Kennedy's quest for the presidency had been gaining strength, and the candidate was celebrating victory in the California primary when he was shot by Sirhan Sirhan at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. RFK died the following day, and the president found himself calling the Kennedy family to offer condolences for the second time in his presidency. Here is his call to Senator Edward Kennedy.

CHICAGO AND CHENNAULT

Johnson's desire to focus his time largely on peace in Vietnam and avoid election-year politics was thwarted over the course of the summer. His vice president, Hubert Humphrey, who had failed to contest any one of the 14 Democratic primaries, secured the nomination amidst anti-war protests and police violence at the party convention in Chicago. Johnson discussed the unrest with the city's mayor, Richard Daley, on August 29.

Meanwhile, Humphrey's opponent, Richard Nixon, recognized that developments in the war might still affect the election, right down to the final days of the campaign. Nixon and his advisors knew that any progress toward peace talks would help his opponent, and they tried to convince the South Vietnamese government to stay away from the conference table through Anna Chennault, a fundraiser for the Republican Party who had long been active in US-Asian affairs.

Johnson discovered these contacts between Nixon aides and Saigon officials just as he had finally convinced Hanoi to attend peace talks, and he was furious. In fact, he was on the verge of announcing the development and a complete bombing halt—the end of "Rolling Thunder"—to the nation on October 31, when he discussed the "Chennault Affair" with Senator Richard Russell (D-GA).

Chennault Affair phone calls

1. Lyndon Johnson and Richard Russell, 30 October 1968:

"We have found that our friend, the Republican nominee, our California friend, has been playing on the outskirts with our enemies and our friends both, our allies and the others."

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

2. Lyndon Johnson and Everett Dirksen, 31 October 1968:

"The net of it, and it's despicable, and if it were made public I think it would rock the nation, but the net of it was that if they just hold out a little bit longer, that he's a lot more sympathetic and he can kind of—they can do better business with him than they can with their present president."

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

3. Lyndon Johnson and James Rowe, 1 November 1968:

"This is the most explosive thing you've ever touched in your life."

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

4. Lyndon Johnson and Everett Dirksen, 2 November 1968

"And they oughtn’t to be doing this. This is treason."

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

5. Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, 3 November 1968

"I just wanted you to know that I feel very, very strongly about this, and any rumblings around about [scoffing] somebody trying to sabotage the Saigon's government's attitude there certainly have no—absolutely no credibility as far as I'm concerned."

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

6. Lyndon Johnson, Clark Clifford, Jim Jones, Walt Rostow, and Dean Rusk, 4 November 1968

"Well, Mr. President, I have a very definite view on this, for what it's worth. I do not believe that any president can make any use of interceptions or telephone taps in any way that would involve politics. The moment we cross over that divide, we're in a different kind of society."

Listen to the entire conversation and read an annotated transcript.

JOHNSON DEPARTS

On November 5, 1968, Richard Nixon was elected to become the 37th president of the United States. Although he won 32 states and 301 electoral votes, his margin over Hubert Humphrey in the popular vote was razor-thin: 43.4 percent to 42.7 percent, with third-party candidate George Wallace taking the states of the deep south and 13.5 percent of the popular vote.

Johnson worked to repair his legacy in Vietnam until the day he left office. With Nixon's assent, the South Vietnamese government finally agreed to join peace talks, but no progress was made before the January 20, 1969, inauguration. Vietnam was Nixon's challenge now.

Johnson returned to his Texas ranch, the war and the presidency behind him. He even grew his hair out in the style of the protestors who had frustrated him so deeply near the end of his tenure in office. He watched as Nixon, still embroiled in Vietnam but in the midst of reducing the US commitment there, won a second term in a landslide reminiscent of Johnson's own 1964 triumph. Two days after Nixon took the oath of office for a second time, on January 22, 1973, the man known as LBJ, architect of massive social programs, massive civil rights advances, and a massive war, was dead of a massive heart attack. He was 64 years old.