The Clinton impeachment and its fallout

America was captivated by the story, especially as it played out in televised hearings, often with graphic detail

In January 1998, news broke that President Clinton had engaged in an affair with a White House intern, Monica Lewinsky. This story was political dynamite, not just because it was a sex scandal, but also because it had dire legal implications. Kenneth Starr's vast investigations into the Whitewater land transaction had stalled, with several prospective witnesses being uncooperative. Starr thought the White House was involved in efforts to buy silence. When a disgruntled White House employee, Linda Tripp, approached Starr's investigators with evidence of the President's hidden relationship with Lewinsky, Starr believed he saw the pattern being repeated once again: Lewinsky was protecting Clinton because she was being bought off with promises of employment. Thus Starr expanded the investigations to include not just the President's financial affairs but also his sexual behavior. Starr's investigators questioned Clinton under oath about his relationship with Lewinsky. This testimony—and subsequent efforts by the White House to deal with Lewinsky-related evidence, which bore some signs of tampering—formed the basis for Starr's subsequent charge of illegal conduct by Clinton and were thus at the core of Clinton's impeachment. Starr was convinced that Clinton had lied in trying to cover up the affair, and that he had instructed others to obstruct justice by lying on his behalf. To many observers, impeachment or resignation seemed to be the only resolution.

The next seven months found the American public consumed by the Lewinsky affair, following every nuance of the investigation by Starr and debating the merits of the case. Nothing like this had so captured the attention of the American public since Watergate and Nixon's resignation from office. Startling revelations came out, including taped interviews in which Lewinsky described details of the affair as well as a dress that contained samples of the President's DNA. On August 17, 1998, following his testimony before a federal grand jury on the matter, Clinton acknowledged in a televised address to the nation his "inappropriate" conduct with Lewinsky and admitted that he had misled the nation and embarrassed his family. But he did not admit to having lied, having instructed anyone else to lie, or orchestrating a cover-up involving anyone else.

Starr then sent his report to the House of Representatives alleging that there were grounds for impeaching Clinton for lying under oath, obstruction of justice, abuse of powers, and other offenses. After a vitriolic series of televised House hearings and the release of thousands of documents—many in graphic detail—the House Judiciary Committee, on a strictly partisan vote, recommended that an impeachment inquiry commence. The House adopted two articles of impeachment, charging the President with perjury in his grand jury testimony and obstructing justice in his dealings with various potential witnesses.

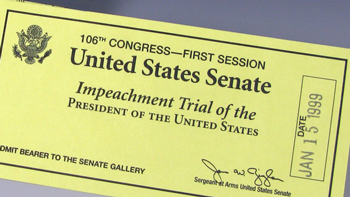

The Senate, charged under the Constitution with judging the evidence, opened its trial in mid-January 1999. It became immediately clear that the Senate would not produce a two-thirds majority vote to convict Clinton and remove him from office. Those voting against impeachment argued that the President's actions constituted "low" and tawdry actions involving private matters, not "high crimes and misdemeanors" amounting to offenses against the state. Those voting against Clinton argued that even in private matters, a President who commits perjury and obstructs justice is subverting the rule of law, and that subversion becomes a "high crime." Clinton was acquitted on both counts on February 12, 1999. On the first, 45 Republican senators voted to convict while 45 Democrats and 10 Republicans voted for acquittal. On the second article of obstruction of justice, 50 Republicans voted for conviction while 45 Democrats and 5 Republicans voted for acquittal. Thus, the second President to have been impeached in U.S. history (Andrew Johnson was the first) remained in office, acquitted and with two years left in his second term.

Impeachment Fallout

In the process of pursuing an impeachment of the president, the Republicans had seriously overplayed their hand. An indication of what lay ahead came when the party actually lost five seats in the House while gaining no Senate seats in the November 1998 elections conducted just prior to the impeachment vote. Traditionally, the opposition party registers significant gains in the off-year elections of a President's second term, and so the Republican loss was virtually unprecedented.

As the impeachment process unfolded, Clinton's ratings in public opinion polls were at an all-time high, hovering at close to 70 percent. Most Americans gave Clinton low marks for character and honesty. But, they gave him high marks for performance and wanted him censured and condemned for his conduct, but not impeached and removed. Many viewed key Republican attackers as mean-spirited extremists willing to use a personal scandal for partisan goals. In the end, voters were happy with Clinton's handling of the White House, the economy, and most matters of public life. Hillary Clinton's public opinion poll ratings actually exceeded the President's, in large measure because of her dignified demeanor during those trying personal times, thus lifting her popularity to among the highest ever for a First Lady.