Transcript

Riley

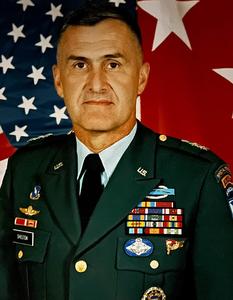

This is the General Hugh Shelton interview as a part of the Clinton Presidential History Project. First I want to thank you for giving us the time to do this.

Shelton

My pleasure.

Riley

This is your story, so anything you want to get on the record you ought to feel free to do, and then I’ll have questions as we go along. We’ve had a conversation off the record about the fundamental ground rules, and the most important is the one about confidentiality.

Shelton

I understand the rules.

Riley

The audience is not me but people down the road who want to understand something about your time as Chair of the Joint Chiefs and before.

A persistent feature of press reports when you became Chair of the Joint Chiefs was that you hadn’t had a lot of political experience. Sometimes press reports like that are not very accurate. Is it accurate in a sense? When you were growing up, did you pay attention to politics? Were you in any way politically active or attentive?

Shelton

I was, but not to the degree that some are. As you know, my advanced degree from Auburn is in political science. But they failed to grasp the assignment I had had in Washington. I was the J-33 for the Chairman. The J-33 is a three-star, the Chief Operating Officer of an organization. I was his principal deputy in operations as a brigadier general. Lieutenant General Tom Kelly, who was the J-3, basically turned to me and said,

I want you to do this stuff for me as a Brigadier.

So I went to the White House. I met in the Old Executive Office Building twice a week. I was the Chairman’s principal deputy on counter-terrorism and drug enforcement.

Riley

This was what time period, General?

Shelton

This was 1987 to ’89. I went over to the White House twice a week, came back, I was briefing all the heavyweights on the Joint Staff in terms of what transpired. I was also preparing papers for the Chairman as he went over to testify before Congress. You couldn’t have a better training ground to be the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs because you got to sit in the tank, the place where the Joint Chiefs meet, a conference room reserved for them. It’s the prerogative of the Chairman who comes in. It’s normally just the Chairman and the principal on an issue that they’re going to face. But I was in there a lot.

So I got to see both how the Joint Chiefs worked under [Barry] Goldwater-[William] Nichols [Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986], which had just come in and was not received very well by the Joint Chiefs. But they had been forced to adapt to it.

I sat in these meetings. I went over to the White House. I prepared papers for Congressional testimony. I was concerned about the Chairman. So I watched CSPAN all the time. I couldn’t have asked for a better job. In going to be the Chairman, I felt as comfortable as if I were getting ready to put on an old worn shoe, because I knew what it entailed. I knew the issues I would face. I knew how important every word you said was when you went over to testify and how that would suddenly be politicized by whichever party didn’t like what you said. It was great.

Riley

How did you end up getting that position?

Shelton

I was one of five brigadier generals, of all services, that they called the DDO, the deputy director of operations. You’re the shift workers. There’s always a general on duty in the Pentagon, and it’s that general. That’s another thing that helped me to know how the place operates.

In those days we recorded every phone conversation that the Chairman (or the SecDef) was involved in, after hours in particular. We were required to monitor the conversations as the DDO. I had my own little office there. The Pentagon operators, who worked for me, were in another room. They were also the guys you used to set up protection against a missile strike against America. We would run operations called

night blues,

designed to train the entire DDO team on how to respond if we detected incoming missiles.Occasionally something would happen. An explosion overseas would light up, and the radar or satellites would pick it up. We would immediately convene a real-world missile conference, as if we were getting ready to be hit. It takes a little while for the over-the-horizon radars to determine it’s not a missile. Five of us did that, and we rotated shift work.

Riley

This was during the [Ronald] Reagan administration?

Shelton

No, it was [George H. W.] Bush. We would monitor these conversations so if the President tells the SecDef,

I want to get this done, and I want to do it in a hurry,

you can get the ball rolling even before the J-3 or the Chairman calls and says we have to do it. You already have taken action. In some cases, if it was a conversation between the SecDef and the J-3, and the SecDef said,I want you to move the carrier battle group out of the Mediterranean into the Persian Gulf,

you’re already putting together the orders that the J-3 will have as soon as he walks in the office, to carry to the SecDef. And you’ve already alerted the carrier to get ready to start moving. It was educational.One of the CINCS—one of the commanders-in-chiefs, as we called them in those days, a combatant commander out in the Pacific—was not doing very well. They were going to fire him. There was a conversation going on between the J-3 and the SecDef, and the SecDef and the President. You’re privy to all that; you see how the system really works.

I sat there as a DDO for a year. I watched this guy, a brigadier general at the time named Craig Boyce, Army, who was a J-33. We didn’t work for him—we worked directly for the J-3—but he was always in our office because we were the 24-hour-a-day op center. If I turned around and looked back to my rear, I had representatives from the CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] and FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation], all of them in this office. All of the different aspects of the Joint Staff had desks in here. It’s a 24-hour-a-day operation, and they worked for us. This was a hub of activity during the off-duty hours. So Craig Boyce would be in that office, and I watched the hours the man worked. All of us sat there thinking, Boy, we don’t ever want that job; it’s a killer. And it was.

One night, after I’d had about a year in the job as DDO—and normally one was kept there for about a year—General [James J.] Lindsay at Special Ops came to the director and asked to take me out of the Joint Staff and let me be the Special Ops liaison in Washington. General Lindsay and I went back a ways. He knew I was a quality guy, so to speak, and he wanted to have me work the Washington area for him. He was down in Tampa, where the Special Ops HQ is. It was turned down.

Later on, a guy came in and asked for me to be Assistant Division Commander of the 82nd Airborne, a job I would dearly have loved to have. That went through the system and was turned down. One has to spend two years on the Joint Staff because that’s what Goldwater-Nichols set as a minimum. So one night BG Craig Boyce, the J33, walked up to my desk, sat down, and said,

I have great news for you. Tomorrow morning the J-3 is going to call you in and tell you you’re going to get my job. He selected you as the man.

He looked at me and said,

What do you think?

I said,It beats a poke in the eye with a sharp stick, but that’s about as much as I can say.

So, sure enough, the next morning, the J-3 called me in and said,You’re the man, I’ve selected you.

I thought, I’d love to have been selected for something else. So I got it.I’ve told people many times, don’t dread going to the Joint Staff, because it’s the greatest educational experience you’ll ever have. If you’re going to go up in rank in the Army and you’re going to become a general—and particularly if you’re going to go up to two, three, four stars—you’ll never find a better training ground than that job.

Riley

You indicated it’s partly because you’re seeing civil-military relations from the White House to the Pentagon.

Shelton

You see the entire thing, the internal workings of the entire joint operation—how the Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, all come together to give you the complementary capabilities you use to fight a war. You’re writing the orders; you’re sending them the tasking to do it.

Riley

Also, there’s a connection with other agencies outside the Pentagon, right?

Shelton

Every agency. I’ll give you an example. Congress allotted $300 million to fight the drug war, the first time in history DoD was going to get involved. They gave the money to DoD and said,

We want you to pull it together because you have a lot of assets in DoD. We know you’re not going to go out and fight the drug war, but you tell these guys what you have, and maybe you can support them.

I was tasked by the J-3 to convene a meeting of all the drug-fighting agencies. We got the FBI the DEA [Drug Enforcement Agency], the customs, the Coast Guard, everybody who has a dog in the fight to fight the drug war, and we brought them into the Pentagon. I’m the guy who had to stand up and brief them: we have $300 million. Here are the assets we can give you, and we want to help you become a cohesive team to fight the drug war. They all sat there looking at me, gritting their teeth. They thought we were going to try to steal their assets. It was a great experience, trying to provide leadership to a group that didn’t necessarily want to be led. They wanted to do their own thing. But we did.

Riley

Were there any surprises in the position, things you found that you didn’t expect to see?

Shelton

Fighting the drug war came as a big surprise because we had never been involved in that. There were things like providing aircraft to the FBI or to the CIA to fly to another country to pick up a terrorist. We had to provide the aircraft so we could then set up a refueling track and fly the individual all the way from that country, wherever it was, back to the U.S. We had to land him in a particular district up in New York where there was a judge who knew how to deal with a terrorist, and do it all under cover, because people in the country we were picking him up from didn’t want anybody to know they were cooperating with the United States to give us this terrorist.

The J-3 called me in and said,

You’re the sole clearing authority for classified information that will be given to the FBI to feed to double agents, or to agents in this country in order to control the flow—

It was a double agent working for the FBI. So I got these highly classified documents. The agent who was trying to get that information wanted us to provide it.The FBI said,

Give us what you can.

I had to go through that classified stuff and sort out what I can give him and what I can’t. I carried it all to the J-3 the first time, and I said,I have this top secret document.

He said,Get out of here; you’re the guy.

I thought, They’re going to hang me out to dry. One day some really top secret stuff is going to pop in the newspaper and they’ll say,Shelton, what did you do?

It was things like that, a comprehensive look at how the entire system worked from things like I mentioned right up through how the President deals with DoD. We’re running an exercise. I’m the center focus for the exercise. It’s a NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] exercise. It’s leading toward nuclear war, and it’s going to force us to react to our plans to reinforce Europe with our troops and to fight the Soviet Union at the time when the Berlin Wall had not come down. We were going to have to fight them.

This exercise is going on, about eight days’ worth. We’re starting to deploy, and suddenly it looks like we’re going to have to use a nuclear weapon because our troops in Europe are getting overrun. All of a sudden I have Margaret Thatcher and Chancellor [Helmut] Kohl and President Bush, all engaged in what was going to be an exercise. The next thing we know, President Bush is coming over and he wants to be updated because he’s getting ready to talk to Margaret Thatcher.

I’m wondering, What’s going on? This is an exercise. Well, they all got engaged, the key leaders of the free world. It turns out it was because of the sensitivity. Some of them knew that the Berlin Wall was getting ready to fall—and it came down a week later. They did not want anything like this to be leaked to the press, particularly if we decided to use a nuclear weapon. We were, in fact, planning to do it, which might lead the Soviet Union at the time to reassess whether they wanted the wall to come down.

Riley

Sure.

Shelton

After it came down a week later, it all became crystal clear why these key guys had gotten involved in this exercise. There was never a dull moment.

Riley

Sure, and it’s pretty clear that the press accounts were overstated in terms of your preparation.

Shelton

Without a doubt. It really made me mad because I was thinking, You just don’t understand what I’ve been put through. It was only a 13-month experience, but it was about a three-year experience rolled into one year. The job was just tremendous.

Riley

You finished that position in what year?

Shelton

I finished up in 1989, and they let me go be an Assistant Division Commander, which is what a brigadier general background needs to do. I got out to the 101st Airborne in July. Then Saddam [Hussein] invaded, and I was on the first airplane of the 101st headed as a line in the sand and to throw Saddam out of Kuwait.

Riley

Right, which you did.

Shelton

Which we did, and stayed there about 11 months. Then we redeployed back to Fort Campbell with the 101st. I had been selected for major general while I was in Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Then I went on to command the 82nd Airborne, 18th Airborne Corps. From there I was selected for four stars and on down to Tampa to take over Special Ops command.

Riley

Just to sequence this with the segment of time I’m trying to cover, where would you have been in 1992?

Shelton

In 1992 I went to command the 82nd Airborne division. I commanded that up until early 1994 or late ’93. The 82nd was a great experience. It doesn’t get any better than that. Then I went to command the 18th Airborne Corps right there at Fort Bragg. I was nominated and selected for the third star. Of course, there you go through the ritual of going before Congress and being grilled, and it gives you a little more insight into how Washington works.

During that time, 1994, I led the Joint Task Force—again, great training for how all the forces come together. You learn a lot in that process. I was commander of the Joint Task Force that invaded Haiti and then I pulled out of there about 45 days later. I went back to 18th Airborne Corps at Bragg. Then in 1996, I was nominated for my fourth star and selected to replace Wayne Downing as the Commander in Chief of the Special Operations Command in Tampa. I served there from early ’96 until I was called by Secretary [William] Cohen and asked if I would like to be the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, or would like to be interviewed for it.

Riley

I’m going to dial back a little bit, because there’s a lot of stuff going on before you get there. I want to ask you first about the incoming administration. President Clinton’s military record—or absence of military record—had created a lot of stir in ’92 in the population at large, and I would guess within the military also. Do you have any specific recollections in ’92 about people looking at that race and thinking, of Clinton in particular, Maybe this is somebody the military would not want to deal with?

Shelton

I don’t remember any of that as part of the Presidential race. I don’t think, to be very candid, that the lack of military experience per se would be something that would cause any—certainly not senior military people—to be overly concerned. We are concerned, for example, when we have elected leaders who can’t relate to what it takes to keep a force trained and ready, how important the quality of the force is.

But we see that in Congress as well. The difference in Congress is it’s one at a time. We’ve watched a steady erosion of military experience in the Congress. It starts to create a concern about how much support you’ll continue to get if they can’t relate to what you have to do and how important it is that you stay trained and ready. Otherwise you go to war unprepared, and it costs hundreds of lives needlessly. But I don’t remember that being a key concern with Clinton.

Riley

How much attention do military people pay to who has the ear of the Presidential candidates? Are you typically following who’s giving advice to the people on military issues, or are you just listening to the words coming out of their mouths?

Shelton

You’re listening to the words that come out of his mouth. You really don’t pay that much attention to who’s behind the scenes, who they’re getting their advice from. I’ve had several Presidential candidates ask me to give them military advice. No one in the military knows that I’m behind the scenes giving advice—I mean for John Edwards. I just turned down an opportunity to be the advisor to [Barack] Obama. I didn’t want to get involved in it. But the military doesn’t pay that much attention. It’s more when individuals start speaking out on particular issues that you form an opinion of them.

Riley

And your sense of Clinton in ’92 was that there was not an elevated level of concern about him on military issues based on the words coming out of his mouth?

Shelton

I don’t recall, and I was a two-star then, 82nd Airborne division, a pretty busy guy. But I did watch CNN, the news, etc. I didn’t have any concern about Clinton becoming the President at that time. It was only after he got in and came out on the gay rights issue that there was a lot of stir and concern throughout the military.

Riley

I’m going to get to that in just a second.

Shelton

I thought you would.

Riley

Did you have a political affiliation?

Shelton

I did not then, and I do not now. Even though I was raised in North Carolina, where they seem to elect Republicans, I was raised in an environment in Speed, North Carolina, where we had only one registered Republican in the entire area. When we’d drive by the house, my mother would say,

That’s where the Republican lives.

So I was strictly Democratic.Riley

I grew up in Alabama, so I understand that environment.

Shelton

That’s the way I was raised. But from the day I was old enough to vote, I’ve always been one who said,

I’m going to vote for the right man and I don’t give a hoot what party he’s affiliated with.

Even though I understand in general what their platforms are, I tend to go with who I think the best leader is going to be.Riley

Do you think that’s true of most of the people you know in the military?

Shelton

I do. Even though the military—and I know some studies done by various universities show that the officer corps is predominantly Republican—I haven’t found anybody in my 28 years in the military who said,

I’m going to vote the Republican ticket

orI’m going to vote the Democratic ticket; I don’t care.

Unlike a lot of Americans who are going to vote strictly party, they don’t. They look at each of the individual candidates and their plusses and minuses and make up their mind which one they think would be the best to lead our armed forces as Commander in Chief.Riley

Take us back and reflect on what it was like to be a senior military official at a time when the Cold War had ended. There was a lot of talk at that time about the

peace dividend

and what that was going to mean. I don’t know that it played a huge role in the ’92 campaign, but that’s the kind of thing you probably would have been worried about based on your own sense of history and your commitment to your institution. Could you talk a little bit about that?Shelton

I don’t think there’s any question that there was quite a bit of concern in the senior military ranks about the

peace dividend.

First of all, the military—the last to want to fight a war—was elated that the Berlin Wall came down and that all of a sudden the dreaded Soviet Union was dissolving. We no longer would have to be concerned about our 4102 (or whatever it was) plan to reinforce NATO. So there was a lot of excitement about that. It was a burden off us. We had a lot of systems in place—like the plane of command and control that we kept airborne all the time. It could now land. We didn’t have to keep it up all the time. Things like that. There was excitement.But there was also great concern that we might start disassembling this great armed force that we had built up. We were already starting to come down in numbers. The Army, for example, was scheduled to come from about 795,000 down to somewhere in the 500,000 range. How much further down will we take it? We still have world-wide commitments like Korea and several others, and plans on the shelf. Until someone says,

Don’t worry about that anymore,

you have to have a force capable of responding.Do we suddenly start creating units that are unready because of this

peace dividend,

and how is all of this going to be managed? That was in the minds of the military.Riley

Were you involved in internal discussions about how you were going to manage this potential contraction?

Shelton

Not in the ’92, ’93 timeframe. At that time I was at Fort Bragg commanding the 82nd. My job there was to keep the 82nd trained and ready. The guys who were going to bring us through that era were Colin Powell and then later [John] Shalikashvili, who had become the Chairman. Those were the guys who had to be concerned about that.

Riley

Now, let’s go back to the early period of the administration. One of the first things that happen when they come through the Inauguration in ’93 is the gays in the military flap. I wonder if you could reflect on that time, what your reactions were and what you were picking up from others in response to this controversy.

Shelton

Of course it meant a major change for the U.S. military, even to go to

don’t ask, don’t tell.

There was a lot of concern, a lot of consternation, over a President who suddenly does that with no military experience. We wondered if he really understood what this might mean to unit cohesion and esprit within the unit—in particular, when you get into certain units like the ranger battalions or into the submarine force. What is it going to do to us if this passes? How are we going to manage it? It was a tremendous shock. It created a lot of anti-Clinton feelings throughout the entire force. It was strong.Again, he’s the Commander in Chief, so there’s not much you’re going to do about it. But you can’t believe the guy has betrayed you in that way. That was the feeling. He doesn’t appreciate what he has. We worked so hard after Vietnam to rebuild America’s force into a quality force, and we had one, no question about it, and still do—considerably better than we ever had under the draft. But all of a sudden, this man is going to do us in. This is going to bring us to our knees; that was the feeling.

Riley

It generated a lot of coffee-table conversation?

Shelton

Without a doubt. It originally was just an open door. We’re just going to start accepting gays in the military.

Don’t ask, don’t tell

came later on. But initially the antibodies that were there for starting to bring gays into the military were really strong.Don’t ask, don’t tell

lightened it a little bit, but still there was an anti-Clinton feeling as a result.Riley

Was there a sense that the Pentagon was properly responding to this at the time? Did folks out in the field have confidence that Powell and others would be able to manage this, or was there a fear that because Powell had been held over—

Shelton

No, it was a feeling that we would be well represented in Washington. But again, if the Congress didn’t step up and intervene, then the President could unilaterally declare that we were going to start taking gays in the military. So there was a lot of concern about whether the process was going to react and salvage something out of this for the military.

Riley

Were people contacting their Congressmen about this? Is that something military people feel comfortable doing?

Shelton

I think that during that period—maybe not so much today as it was back then—the answer is no, you normally don’t do that. In the military, to get a Congressional inquiry— A Congressman sends a little note down to Fort Bragg. It normally goes to the Pentagon and comes down. He would like to know about a certain issue. Maybe Private Smith’s mother has called in and said,

My son’s being beaten and flogged three times a day with a bull whip. I need you to stop it, Mr. President or Mr. Congressman.

You get an inquiry. Are you flogging this guy three times a day, and if so why? And you answer that.Well, at the senior levels, you understand it’s all part of a process. But, down at the unit level, it’s a big deal. It’s a black eye that you got a Congressional inquiry. Why did a Congressional come in? So you normally don’t use the Congressmen. Once you get senior in rank, and you understand why this process is the way it is and how this is a good thing. In those days you wouldn’t call your Congressman. We did feel that we’d be well represented. But we also knew that the President had the power, if he wanted to—if Congress didn’t intervene—to make it unilateral.

Riley

Colin Powell had been held over from the previous administration—

Shelton

Just like I was in the Bush administration.

Riley

Exactly. Does that create any anxiety out in the field about the relationship?

Shelton

To the contrary. I think it’s a feeling that you have an experienced guy in there, and you’re not dealing with a neophyte trying to learn his job at the same time the President is. It’s the beauty of our system. He doesn’t get a brand new Joint Chiefs Chairman the day he shows up. He’s going to live with the previous guy. The military is apolitical for good reason. And you have to work hard to keep it that way when you’re the Chairman. At least from my perspective, that’s the way you do it.

We all felt comfortable. Colin Powell was experienced. He would fight for what’s right. We liked the Powell doctrine. He knew the political landscape very well, having been National Security Advisor. So that was very comfortable for the military.

Riley

Had you known Powell from your time working in the Pentagon or earlier?

Shelton

I had. And he had been down to Fort Bragg several times as well while I was in the 82nd, the 18th Airborne Corps.

Riley

Your relationship with him was good?

Shelton

It was good, yes. Colin’s a good friend, and was then. So again, all of us who knew Colin Powell were very comfortable that he was in the position. We knew that he’d do everything he could to control the damage—and we think he did, given the political environment.

Riley

So you were comfortable with the way this all worked out.

Shelton

Yes.

Riley

What about the Secretary of Defense at the time. You have Les Aspin coming in during the first term. That was a controversial appointment. How was that viewed?

Shelton

From my perspective, none of us felt that we were going to be well served by Aspin as a Secretary of Defense, but we didn’t know that much about him in terms of how— You know, people change when they go into certain jobs. While you may get a guy in there who wasn’t very strong on defense when he was a Congressman, suddenly it’s his baby now, and he’s going to do everything he can because it protects America’s national security, or is a key part of it. So you wait and see how the guy is going to react. Of course, he wasn’t there long enough to see very much.

Riley

Had you known Aspin before?

Shelton

No, I had not.

Riley

Were there any other issues we ought to talk about in ’93? I’m trying to track before Haiti, which becomes a very important story. Were there any other appointments at the senior level—Aspin’s deputies and assistant secretaries? Anything that had any particular relevance for you?

Shelton

Not for me. Again, I’m a two-star, 82nd Airborne, later on become the 18th Airborne Corps. My focus there is doing the work in my lane and keeping that force trained and ready to go. A key guy like Aspin gets your attention, and you say,

What’s this going to mean to our force and how is that going to affect DoD?

But below that, you don’t pay any attention to it. He’ll bring in a bunch of political wags to do whatever the bureaucrats do and then be gone. That’s the attitude down at the lower levels.Riley

Let’s take up Haiti. Is this something on your radar for a while before you end up heading down there?

Shelton

Ironically, when I was commanding a brigade in the 82nd— I’m going to carry you back now to 1983 to 1985. I was commander of a brigade. One day I got a call from CG [Coast Guard]. I was what they call the

division ready brigade

in the 82nd Airborne. That was the brigade that would be the first to deploy. We had two hours to start moving toward the holding area, and 18 hours later the first planes would take off. That’s the kind of readiness we lived with. We kept that for six weeks, and then we rotated through two more cycles of different types of missions, and then we’re back as the ready brigade.Riley

Okay.

Shelton

So I was the ready brigade. I got a call,

Get ready. We’re going to jump you into Port-au-Prince, Haiti; there’s a crisis down there.

I ran back. The plan on Haiti was about three pages long. It had Port-au-Prince airfield on it, and that was about it. That was all the plan I had. So we scramble, we start getting ready, and we start drawing up plans to jump into Haiti. We’re getting ready to get up to the N+2 room at the 82nd Airborne, which is where we get the briefing from the division staff. Now everything is starting to roll. All our equipment is rigged for heavy drop and to be ready to be parachuted. The troops are getting ready. Just as all that’s starting to take place, I get the call,It’s off. Stand down.

I didn’t know what generated that, but I knew we weren’t prepared to go to Haiti. We didn’t have a good plan.So, all of a sudden in 1992, I found myself back in the 82nd as the Commander. I looked at the plans, and the plan for Haiti was a little bit thicker. That had generated some interest at division headquarters. So we now had about a six- or seven-page plan. But it was still not very good. So we worked on that some as part of how we continue to improve our plans. We got it up to probably about ten or twelve pages, but again, it was not a great plan. It was something we didn’t envision, because Haiti is just a pain.

Riley

What are you consulting? You say you’re working up plans. Are people making field visits down there to reconnoiter?

Shelton

You talk to people who’ve been down there. You have some Special Ops guys who’ve rotated through down there to do various things. You talk to them. You do a lot of research on the Internet about what kinds of forces they have. You look at aerial photos of the place and put that in the folder. You request aerial imagery from satellites of the Port-au-Prince airfield, and that goes in the folder. You continue to refine the plan. It’s not much of a real plan, because you really don’t know what the mission would be. What did we go to Haiti for?

Riley

Do you have corollary plans for every spot on the map?

Shelton

Lots of places. It’s normally generated when you have a crisis there. You jump through it and form a plan. Then, if you don’t carry it out, you just stand down. Grenada is a good example. That had taken place three days after I joined the 82nd in 1983. Fortunately, I was the support brigade then, and I pushed out the rest of the division.

But at any rate, I go up to be the Corps Commander in 1993. I asked to see the plan on Haiti. It’s the plan we worked in the 82nd. I called in my plans officer, a guy named Bert [William B.] Garrett, a Major at the time, and I said,

I want to take this plan on Haiti and flesh it out. I want to develop a really good plan. Let’s not assume we’ll have to do it by ourselves, because we could probably get some Marines if we asked for them. We could probably get all the support from the Air Force. So let’s really look at how we would go into Haiti right now, given what we know about the force that’s there.

Riley

Are you moved to do this just as a routine course of action, or are you following events in Haiti and thinking things are beginning to heat up a little bit down there?

Shelton

There had been a couple of spikes in Haiti, and that got my attention. What if they called me one day and said,

Jump the 82nd in down there

orGo to Haiti.

That piqued my attention. So I told the planner,Let’s develop a plan.

I gave him the guidance:Use a joint force, and let’s get something going.

About a week later, he came back down and it was a pretty decent plan. It was looking pretty good. We spent three or four hours on it. I said,

Let’s use some Special Ops.

I know what they’re capable of. I’d been very familiar with Special Ops; they were right there at Fort Bragg. So we integrated them into the plan. Then we put it back on the shelf.Then we had the incident in Haiti where the Navy ship was turned around. I bring the plan down. Let’s look at this again. I take another look at it. Shortly after that, I got a call from Admiral Paul David Miller up at ACOM [Atlantic Command]:

Come up here, we want to talk about Haiti.

So I took my plans, I took Bert Garrett, I got on a C-12 aircraft, and I flew to Norfolk. They looked at the plan. We started talking about it. I said,

We have a plan, let us show you what we have.

We laid this out for them. They took the plan and said,Let’s look at this, and we’ll get back.

Basically, over the next several weeks, that plan we had developed turned into what became known as the ACOM plan to go into Haiti.Miller called me up and said,

If we ever do this, you’ll be the joint task force commander. It looks like you have a good plan here, and we’ll just issue this back to you and say ‘Go do it.’

I said,I assume, then, that you’ll provide the resources that this plan takes: Marines, Navy, Coast Guard—to set up a Coast Guard bridge so the Army aircraft flying over land could be rescued if they happened to go down in the water en route.

He said,Oh, yes. You just continue to refine the plan.

At this time, we started turning the burner up because there had been a lot of activity in Haiti and we noticed that. So we really turned it up. Then one day I got a call from Miller saying,

This is getting really serious; you’d better do rehearsals or whatever you need to do to make this happen.

He had a meeting up in Norfolk and brought in what were going to be the component commanders. I had the Marine three-star; I had a Navy three-star. The Navy representative was Admiral Jay Johnson, later to become the CNO [Chief of Naval Operations] and who was there when I was the Chairman. We brought in an individual from the Coast Guard, a Captain who came in for that particular meeting. So we had Army, Navy, Air—we brought in a three-star from the Air Force whom I happen to know very well, a guy named Jim Record. I had worked with him when I was in the J-33. He had been the Ops officer down in Tampa with CENTCOM [Central Command] who was doing all the Persian Gulf operations, which we were doing throughout my tenure. So I had another familiar face there, a guy I really loved. Two of these guys were great.Shortly after that, we ran a joint task force exercise. It wasn’t a Haiti scenario; it was another scenario, but Bill Keyes, the Marine, was the Joint Task Force commander. It was at Camp Lejeune. I was going to have to come in with an Army task force and replace Keyes as the Marines pulled out. I would take over the operation. The continuity would be Admiral Jay Johnson, who would be the three-star Navy working for Keyes who would stay and work for me.

We ran this exercise, and during the exercise I had a chance, of course, to get to know Bill Keyes a lot better. I got to know Jay Johnson really well. We did that exercise. It really worked well. Jay Johnson and Bill Keyes and I worked a little bit of Haiti off to the side. We all got in a room and went over this thing. Then I got back to Fort Bragg. The exercise had gone really well, and Miller called me and said,

Come up here; this is really getting hot. I’m going to bring in the other commanders you’ve asked for in this.

So we had a big meeting in Norfolk. We went through the basics of the plan. I got great support from all the component commanders. I’d given the Marines their own amphibious operating area up north at Camp Haitian. I had Air Force involved in the lift as well as flying air cover for me. I had Special Ops involved. I also asked for two aircraft carriers to put Army troops and Special Ops on. Everything went well until Admiral Miller started trying—I think for political reasons within the Navy—to force me to use some Navy air, because they were going to take the aircraft off both carriers. Navy was not feeling good about aircraft carriers being used with Army.

So I said no. I didn’t need them. My biggest concern in Haiti was, first, fratricide. The second one was safety, just in general. The third was the enemy. So I didn’t need any more air in this area. It was too small an area, and I had the Air Force. I just didn’t need Naval air.

Admiral Miller said,

What do you guys think about this?

talking to the other guys in the room, to my fellow three-stars. I’ll never forget it. Bill Keyes said,You just heard the Task Force commander tell you he doesn’t need your God-damn Navy air in there, so why don’t you just not push it?

Bill Keyes hammered it. I tell you, he nailed it. Jay Johnson said,I agree.

So I didn’t have to take the Navy air.We went through this, and I said,

Guys, I want to run an exercise at Fort Bragg. I have a big one coming up in about a week to ten days, and I’d like to turn that into a rehearsal of this plan. We’ll do it in remote locations so no one sees it all come together. But every piece of it will be part of our Haiti scenario, and we’ll exercise it.

They all agreed.A few days later we had a big rehearsal down at Fort Bragg. It was the Haiti plan. We used a room that we had set aside, a Special Ops room, top-secret data, etc. We built a model of Haiti about 15 feet by 15 feet, a to-scale model. Up on the walls around this room was the execution matrix for how we would do this. It was done by force: Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, Special Ops, Coast Guard.

It started off at something like H-hour being the time we would initiate first contact in Haiti. We backed it up, H minus 36. What’s going on 36 hours before we do it? And we came all the way around to H plus 4 days. I had a couple of guys dressed up in referee uniforms, carrying big sticks. I had all the 21 flag officers, admirals and generals—in one room, who were going to be the commanding forces. My staff and I orchestrated this thing.

We said okay, H minus 36. Army, what are you doing at that time? I had the Army guy tell me what he’s going to be doing. Okay, Navy, what are you going to be doing at this time? The Navy admiral spoke to that—all the way around the room until H plus 4. We started at 8:00 in the morning and finished about 4:00 that afternoon. Everybody then understood what the other elements were doing at the same time they’re doing it and how we were going to synchronize this entire operation.

Riley

You’re pleased with the results?

Shelton

I’m very pleased with that. Now, about 3-4 days later, the exercise kicks off, and we actually run it by this matrix. The difference was that the Marines are running theirs at some other location. Air Force is doing it in two locations; one of them is Fort Bragg. Army is doing their thing at Fort Bragg. They’re dropping all the heavy equipment, dropping the paratroopers, just as if it’s Port-au-Prince airfield. All of it was being synchronized from our war room at Fort Bragg. We made sure everybody was doing everything they said. They reported in when they completed it. I was very pleased with how that went. I felt confident that we had a good plan; this thing would work.

About two or three days after that exercise, we made some minor tweaks, revised it. I flew back up to ACOM and briefed Admiral Miller on how everything went and how we stand. I got back to my office, and he called and said,

I want to change something. I want to put the Marines into Port-au-Prince instead of up at Camp Haitian.

I said,Why would you want to do that?

He said,I just think that’s a better fit, a better place to put them.

Now, in the plan, the Special Ops were going into Port-au-Prince because they were very small, discreet targets, and they’re ideally suited to take them. I had put the Marines up at Camp Haitian, because I could get in an amphibious operating area which allowed them to use their aircraft, their ships, and the Marines, and not have to go through the coordination required when you start mixing forces.

Riley

Okay.

Shelton

Port-au-Prince was jammed chock-a-block full with Army 82nd Airborne dropping in and Special Ops taking very specific targets. It didn’t work. I got on a plane and flew to ACOM at Norfolk, and I had a one-on-one with Admiral Miller. I said,

This can’t happen; I’m not in favor of what you’re proposing. Let me show you why.

I showed him how, by doing that, the Marines coming into Port-au-Prince would be running perpendicular to the flow of operations: Special Ops coming in out of Guantanamo and 82nd coming in out of Fort Bragg. All the air flow is going west to east, and now he’s proposing Marines coming in basically from south to north. I said,

This is a disaster.

He looked me dead in the eye and said,Are you telling me you’re not going to do it? If I want to do this, I have to get a new Joint Task Force commander?

I looked at him and said,

Admiral, that’s exactly what I’m telling you. This is a lousy fix to the plan. It will result in loss of life. That’s my concern. It doesn’t make sense. I’ve talked to Bill Keyes, the Marine task force commander, and he’s not in favor of doing this either. This is a bad thing.

The real driving factor there in my opinion was publicity for the Marine Corps. All the 400 media that had already started assembling in Port-au-Prince were going to be in Port-au-Prince; nobody was going to be at Camp Haitian. I had never even considered where the media would be, other than not having their hotel targeted, making sure we stayed away from the hotel where they were staying. And we knew where that was.By the way, we had undercover guys on the ground down there already. We were getting pretty good reports coming out in terms of what the Haitian military did at night, what their activities were during the daytime. That allowed us to be very precise in who we would have to kill if we were going to do the invasion, and where we could probably be in their place of business before they got to work the next morning. All that had been worked in.

So Admiral Miller said,

Okay, do it the way you planned.

Riley

So the pressure coming from Admiral Miller is inner-service rather than political pressure.

Shelton

Right, no political pressure. Two things happened after that. He called me up and said,

Now that the Marines are not going to participate, I need you to use the 82nd.

My original plan had been to secure the Camp Haitian area with two battalions of 82nd jumping in, primarily for speed: take it right now and be done with it. Then bring the Marine forces in, leave the 82nd, they re-deploy, the Marines now own that AOA [Amphibious Objective Area]. That was part of our plan.Riley

Okay.

Shelton

I had decided later that the Marines would be better, just go ahead and take it. They could do an amphibious assault. They could get their force recon on the ground and basically do a great job at that. So I revised the plan. Suddenly Miller said,

Put the 82nd back in.

He didn’t want to keep the Marines floating around in a ready status that long. They were doing other things, exercises and whatever. We didn’t know when we would have to execute this plan. So rather than keep them bobbing around out in the ocean, waiting for the plan to develop, he wanted us to go ahead and use the 82nd because we could fly them right in.Got it, we can do that. I didn’t like it as well, but it would work. Now we have all that in place, I’m feeling very comfortable with the plan. I then go to Harvard for two weeks. All this is cooking. My plan is active. But I had been scheduled to go to the national security course at Harvard.

Riley

[laughing] Forgive me, that just—

Shelton

Yes, right in the middle, what a great deception, right? The guy who’s going to lead the invasion is up in Harvard right now, so the Haitians don’t have to worry about that. It was good deception. I carried my secure phone with me, and I’d plug in. At noon time I’d run back to the place I was staying and call back in, and at night I was back on the phone going over the plans and tweaking things. Finally I got back. Two weeks went by. This plan was still perking.

Riley

You finished your course.

Shelton

I finished the course. I had driven up to Cambridge. I drove back down 95 and went back to Fort Fisher, South Carolina, where my family had gone. We had planned a vacation for three or four days. I got in there Saturday morning. My Chief of Staff called me and said,

Boss, this thing is really cooking right now. I wasn’t going to bother you, but I think it’s probably time you came back.

I said,

Okay, I’m on my way.

So I loaded the family up, and we went back to Fort Bragg. I got a call then from Admiral Miller on Sunday or Monday, telling me that President Clinton wanted to hear about the plan. He was coming to Norfolk, but he’d like to teleconference me so no one sees me come to Norfolk. So we set up a teleconference in the secure facility at Fort Bragg.President Clinton came in, and it was kind of funny. Admiral Miller briefed him at ACOM, and I was watching by telephone. The Forces Command component commander was going to be Denny Reimer. He asked him how things looked from his perspective and got a head nod; everything was going well. He went to the Marines and asked them. He went to the Navy and asked them. Then he said,

Well, Mr. President, that concludes our briefing.

I’m sitting there thinking, You have to be kidding. I’m the Joint Task Force Commander, and you’re not going to even ask me? I don’t know whether somebody handed him a note. He said,

Oh, my God, I forgot. I need to ask the Joint Task Force Commander, Hugh Shelton, sitting at Fort Bragg.

So I came on and basically just gave a little thumbnail: I think we’re up and ready to go whenever you’re ready. We need 18 hours’ notice; that’s the flow for Fort Bragg to be ready to go and the Marines to respond, get their stuff in position. President Clinton asked me three questions, one of which was,

Are you using any Reserves or National Guard in this plan?

I responded,Yes, we have some Marines that are National Reserve, Army that will be a part of it. Those guys are already here at Fort Bragg training; it won’t be a big deal. They’re already on their active duty cycle. We have some reserve aircraft, part of our Special Ops force, that will be involved. They work out of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

He said,

What are your greatest concerns in this operation? What’s the highest risk thing you think you’ll encounter?

I said,Number one is fratricide of our own troops because of the close proximity; we’ve gone to great extremes. I have a lot of aircraft that are going to be operating in a very small area, so safety is a great concern. And the third thing would be the enemy.

He laughed and said,

Well, it’s good that the enemy is the third priority.

I said,From a safety and fratricide concern, they really are third.

He asked me one or two other questions. That was my first encounter with the President other than the aircraft crash that happened at Fort Bragg on the day they had all those admirals and generals assembled. Two Air Force planes ran together. You may be familiar with this.Riley

I don’t remember that.

Shelton

It occurred in 1993. An F-16 and a C-130 were coming in to land. The aircraft controller made a mistake, and they collided. The two F-16 pilots bailed out. Their plane came careening down into Pope Air Force Base, hit— These two guys parachute out and land there, right in front of their headquarters where their Commander is having a meeting. He saw two parachuters land outside, and about the same time he saw a fireball down at the end.

The F-16 hit a parked C-141. A fireball ensued and went down between two buildings. Back behind those buildings I had 125 paratroopers preparing for an airborne operation. I had 123 casualties there, many of them burned severely, and 19 died. Four of them had amputations immediately. All survivors were hospitalized, about 100.

President Clinton flew down the next day. I think it’s important that I relay this. I’m interrupting the Haiti—but President Clinton flew down. I received the call that night that he was going to come in. He had a nationally televised conference from the Oval Office, but I was told that he was going to be coming down and would arrive at 10 o’clock that evening to visit the hospital. When you’re going to have a Presidential visit, you have to jump through it. There’s transportation to be thought of. My job at J-33 had prepared me, because I knew what an entourage he traveled with and the support requirements. So we jumped through it.

We got every general officer sedan and van on post and had designated drivers. We laid on military police escorts. About 8:30 or 9 o’clock, I got a call:

He’s not coming tonight.

So I said,Stand down, the President’s not coming.

The next morning at 10 o’clock I was getting ready to go upstairs to present the Audie Murphy award to seven Fort Bragg soldiers, noncommissioned officers. Only a very select group of people ever get selected to join the Audie Murphy Club—top notch, noncommissioned officers or sergeants. It’s very important to them. They had their families there.So I told my secretary, Marie Allen,

Okay, tell the Chief, same plan we had last night, get it started. I’m going upstairs and present these awards.

So I went up, spent about an hour, and came down at 11 o’clock. I said,Marie, what’s going on?

She said,The Chief has everything lined up.

I said,Okay, I’ll leave and go to the airport.

They said,We just got the call; he’ll be in the blocks at Pope Air Force Base

—meaning he’ll stop—at 12:00 sharp.

I said,

Okay, I’ll be standing there at 12:00 sharp.

I walked down to talk to Brigadier General Frank Akers, the Chief. I said,Frank, everything set?

He said,It is. The band’s laid on; we’ll have an honor guard for him with flags. The Secret Service, the Fort Bragg office, has gotten involved. They checked our plan and they love it because it’s taking a big load off them, so everything seems to be in accordance.

I said okay.So about 20 minutes to 12:00, I started on the 10-minute ride over to Pope to be standing there when he arrived. He had landed. We immediately put him in the van. The Army Chief of Staff had flown down either with him or in a separate plane. We had vans laid on for the media that would be with him. So all that was set. We went straight to the hospital. President Clinton that day talked to every single troop in the hospital, visited every bed. I was amazed.

Then he got ready to leave. As we got to the hospital exit, I said,

Mr. President, there are three other troops on the top floor. They are severely burned, and they’re not going to live.

The doctors had said they had zero chance of living, which is why we had not tried to fly them to San Antonio, where we had sent some of our severely burned, but not so severely we were afraid they would die. Those nine had gone to the University of North Carolina Burn Center. The three guys upstairs were just on life support.President Clinton said,

I really want to visit with them; let’s go up where they are.

So the hospital commander and I went upstairs to the top floor. He had to change clothes three times, but he went into each module where they were, stood beside the bed, kind of put his hand on the bed. It looked like he was praying, standing next to them. He went to all three rooms. Then we went downstairs.As we were going down the stairs, Harold Timboe, a colonel at that time, later on commander at Walter Reed as a major general, said,

Mr. President, thank you for visiting with these people. I think it’s important that you see what George Washington had to say about the Commander in Chief.

This surprised me, but it was an excerpt where George Washington had said,The greatest attribute of a commander is that he takes the time to visit with the sick and the infirm, wounded—

He said,I think that George Washington and you had a lot in common.

Riley

How about that.

Shelton

It was pretty good. So we went downstairs. The Chief, General [Gordon] Sullivan, President Clinton, and I got back in the van and started back to the airport. But before we did that, as we went out, a lot of the family members who had gotten word that the President was there had gathered outside. So he spent a good 30 minutes walking around, shaking hands and thanking them. He got back in the van. As we were going over, I pointed out the [Zack] Fisher House, a house built by the Fisher Foundation—there are now about 75 of them around the country. It’s about a half a million dollar project to build one, like a Ronald McDonald House where family members can stay when they have people in the hospital, at much reduced rates, beautiful homes, well appointed and everything.

So he said,

Who is this guy?

So I explained to him that Zack Fisher was a guy up in New York. I went through the entire thing about Zack and his wife. He said,I’m going to make a note to call him when I get back and thank him.

We got back to the airport and President Clinton got out. The honor guards lined up again. I walked him up to the edge of Air Force One and said,Mr. President, I can’t tell you how much this means to the troops. Thanks for spending the time today.

He looked at me and said,I should have come last night, but my handlers convinced me that because I had that national press conference last night any press that showed up down here would be interested only in what I said last night and it would take the focus off my visit with the troops. I relented and said okay. But I woke up this morning about 2 o’clock and said, ‘I should have gone to Fort Bragg; that was the right thing to do.’ So I waited until people would be in downstairs, and I called down and said, ‘Get the plane ready, I’m going to Fort Bragg.’

Immediately they gave me a litany of reasons why I couldn’t go: ‘You have a state visit here; you have an interview with this guy; you have this schedule.’ I said to them, ‘Look, I’m the President of the United States. Read my lips: I’m going to Fort Bragg. Get the plane ready.’ So after I went downstairs, they said they had it ready and everything was set and we would take off around 11:00 and land at 12:00. I just knew it was the right thing to do.

I thanked him again for coming and said,

It really was the right thing to do.

He got back on the plane. I already had respect for him because I knew he was a brilliant guy from my previous interview with him on the Haiti operation.I had a lot of respect for the former Commander of Fort Bragg, General Gary Luck, who had gone to Korea. Ironically, when he got wind that the President was going to fly down the day before, he called me up and said,

Listen, the President has been to Korea. We had him for dinner at the house. Leah [Luck] and I really like Bill and Hillary Clinton. Just keep in mind he’s a politician; you’re going to like him, but remember, what you see is not what you get.

So my antennae were up. I kept saying,

What’s not sincere about this guy?

But that was a good insight into the man. I saw there was great feeling and compassion, and he didn’t bring any press in the hospital with him. He didn’t allow them to come in. Nobody knew he went up to visit those three guys who were going to die. That said to me, there’s more to him than just glitter. There really are some sincere feelings for our men and women in uniform.Riley

Sure. The sense of empathy that he has for people is something we hear over and over again, as genuine.

Shelton

It definitely is genuine. He left there that day and went back. It was just a short while after that that we got the orders, after I had been called back from vacation. The wheels started rolling, and we implemented the plan.

Riley

Your teleconference occurred after the visit?

Shelton

Yes, after the hospital.

Riley

In the teleconference, the first question he had was about Reserve and National Guardsmen. Did that strike you as an odd question? Would that be a typical question you would get in that kind of environment?

Shelton

It would have been except for the fact that something had occurred previously in his administration, about the use of the Reserve and National Guard. I’ve forgotten what raised the issue.

Riley

It wasn’t clear to me.

Shelton

That was why I didn’t think it was odd. I hadn’t thought a lot about it, but I did know what part of Reserves we were using. But because of that previous publicity about the Guard and Reserve, it didn’t strike me as odd.

Riley

He had been a Governor, and I didn’t know if that was just a natural question to come to his mind.

Shelton

It might have been otherwise, but it was that other issue somewhere along the line.

Riley

You’ve gotten us to that teleconference. Having dealt with him in the teleconference, your sense was that he was on top of things?

Shelton

My impression of him—and it remained true throughout my association with President Clinton—is that he’s a quick study. He may not have served in the military, but he grasps things very quickly, has a razor-sharp mind. He can separate the wheat from the chaff. He sees what the big issues are, the important issues, and he’ll home right in on them. I saw that the first time in the teleconference, but every other deal I had with him, even after becoming Chairman, was the same. I didn’t have to worry about how complicated or complex it might be; he could pick it up.

Riley

So let’s pick it back up from the story after the teleconference.

Shelton

At that point we went back to my headquarters, to what I’d say is a very high state of alert. I told all my component commanders,

It looks like this thing is going to go, no question about it. I don’t know the time right now, but the President has gotten involved in it.

I went off to my course, and while I was there, things started to go to hell in a hand basket in Haiti, so to speak. By the way, one part of the vignette at Harvard was on negotiating. It was about an eight-hour exercise and it was hands on. We had class, and then we followed up with a hands-on exercise.

Riley

That’s the [John F.] Kennedy school?

Shelton

It’s part of the Kennedy School. I was sitting there thinking, What in the hell am I ever going to use this for? I don’t negotiate. Maybe I can use this when I buy a car the next time. It really was well done.

So I got back to Fort Bragg. Now things were really heating up. I got the call from the Chief:

Come back to Fort Bragg from vacation.

I got back, and sure enough, the next day I got the call from Admiral Miller: it’s a go. We’re looking at going at this particular time. They’re working right now on getting a negotiating team to go in. [Jimmy] Carter and [Samuel] Nunn and Powell are going to go in and try to talk him out of it. But they’re going in on this date, and you’re going to get ready to start flowing the same day. They’re either going to acquiesce, or just as soon as we get them out of there, you’re going in.Riley

Is that how the diplomatic and political information is coming to you? I guess you’re watching CNN and getting information there, but are there any other back channels—?

Shelton

I’m getting everything the intel community has on what’s going on down in Haiti right now. I’m also getting reports from people on the ground in Haiti, the undercover guys, in terms of what’s going on down there and in terms of activity levels, which is zero. The Haitians are being Haitians; they’re laid back, and nothing is really changing. There’s no sense of increased activity on their part, no high state of readiness of their military or their police force. I’m very comfortable with the flow in terms of what we’re getting.

We’ve done some other things. There’s now a submarine offshore that’s picking up a lot of intel and feeding it back to us. I’m feeling good, and things are working well, so now it’s just a matter of when we go. Now I get the word that ACOM is getting ready to send me a deployment order, and it’s going to have a specific time and date on it. That’s what will start the real flow. That comes to us at Fort Bragg. We immediately send out our own op order to our components and say,

Here’s the plan, and here’s the date and time. This is H-hour; we now have it established.

So, when we establish that H-hour—the time the paratroopers will come out of the planes—now the matrix kicks in. Everybody’s going to start following what’s on the matrix and reporting in. We set up at that time a Joint Task Force headquarters in some buildings over in the old area of Fort Bragg. We had already done this months ahead of time and had phone lines put in and everything. So we activated our Joint Task Force headquarters, and a liaison from each of our forces starts flowing into Fort Bragg. We get a full headquarters set up on the ground.

We had an air ops center established. General Jim Record and his crew came into Fort Bragg and started setting up the air operations center, about 600-people strong, a big operation. We were doing all this so that we had a reduced headquarters footprint, and we were basically working out of Fort Bragg with a forward element. That’s where everything flows. All of my intel assets, which is very big, doesn’t have to go aboard the [USS] Mt. Whitney. It can stay right there at Fort Bragg.

When I got the word we were going to go, the first thing I wanted to make sure I had was a capability to use our land-line system in addition to our satellite communications. So I called Jay Johnson, and one night under the cover of darkness, we flew an Army humvee vehicle that has MSE [mobile subscriber equipment]—our switchboard, our server, our router-type system—in the back. We flew it to Jacksonville, Florida. The Chief, a commo team, and I loaded this thing on the USS Mt. Whitney, and a couple of smart enlisted guys from the Navy and a couple of brilliant communications guys from the Army figured out how to hard-wire this MSE system into the ship. Now down in the war center, you can pick up the telephone and talk to anybody on the MSE network. Necessity is the mother of invention. So now there’s an Army system on the Mt. Whitney. We didn’t lash it down at that time; we carried it back with us. Then, when we got the order to go, one of the first things to deploy was that system down to the Mt. Whitney.

Then things start flowing. We were monitoring all that right at Fort Bragg. Let me back up. Two days before we were going, I got a call from the Army that they wanted to send down about 300 members of the media for me to brief. They wanted me to go into all the top secret detail about how this plan would unfold. My first words were,

You have to be kidding.

They said,No, you need to be very honest with them, lay it out. They’ve all been sworn to secrecy, they all know the rules, they all will act responsibly.

I said,

Really?

They sent them down. I thought my career was probably being terminated as we stood there and briefed them in great detail about how this plan would unfold. Then we took them and embedded them throughout the force. I had different people marrying up with different elements. All my people were told,Protect them; put them in the force. Don’t expose them unnecessarily to hardships or danger.

And they went in.About that same time I got a call from the Chief of Staff of the Army saying the Washington Post would like to have Bradley Graham go with me. I said,

You have to be kidding.

They said,No, they want him to live with you for the operation.

The funny thing was, up at Harvard, I’d been in a seminar for two weeks with Bradley Graham, and I’d gotten to know him well. I liked him. He and I had become friends. So I said

Okay, send him down.

They sent him down. So Bradley Graham, the Chief of Staff, and I, 24 hours out, flew to Guantanamo Bay, where we had sailed the Mt. Whitney. It was sitting there, and we boarded. Then we set sail and headed down into Port-au-Prince. It was about 12-18 hours out, but that thing takes some sailing time.Riley

You said earlier that you knew the hotel where the media would be staying, but that wasn’t in anticipation that you were going to have these 300 people embedded with you. So you have 300 more people to account for.

Shelton

That was the media that was already there. Now these 300 people are going to be embedded, and they’re going in.

Riley

How complicated is it to do something like that?

Shelton

Not hard. The biggest thing is transportation and getting them out to marry them up with the various forces and making sure they can accommodate them. All that had been worked out very easily by the task force.

Riley

You’re getting this from sources—if you wanted to raise an objection at that point, it wouldn’t—

Shelton

The plan had all been approved in Washington; we were going to do it. It was coming out of the office of the Secretary of Defense.

Riley

Got you.

Shelton

So we put them in. It will create complications later, because part of our force is going to fly with the UH-60s that night, stop on a little remote island, refuel. (That had all been laid on. We had flown that stuff in with C-130s, using what we called bladder birds. U-130s are just filled with bladders, and we run refueling out of them into the helicopters.) This is jumping ahead a little bit, but when I turned the helicopter force around to go back, because I wasn’t going to need them, it left a guy—I’ve forgotten who it was now, but it was one of the prominent newscasters, somebody like Sam Donaldson, stuck out there. He’s saying,

I want to come home. How the hell do I get there?

Now this is a flap, how do I get this guy down here? You just deal with it.At any rate, we sail into the claw of Port-au-Prince, about 50 miles off land, and it’s about this time that Carter and Nunn and Colin are down there negotiating. We’re following that live on CNN on the ship.

Riley

But you don’t have any independent communications with those three?

Shelton

Not with them. My communications are back to ACOM and to Shalikashvili.

Riley

Okay, and those three guys are presumably communicating directly to the White House.

Shelton

Shali is standing in the Oval Office in the White House. He’s walking out occasionally, I guess, into the Cabinet Room or into Betty’s [Currie] office outside to make a phone call. I’m talking to him. I’m on my time schedule now. This stuff is flowing. The Fort Bragg paratroopers are loaded, and the first planes have taken off; they’re en route.

He says,

I need an hour. Can I have another hour?

I looked at my time line and said,Shali, I can give you one hour, but if you push me past one hour, I can’t guarantee that I can stop the force. If I lose communications with them, they’re going.

He says,Okay, one hour, I’ll be back.

I’m watching CNN. They’re showing live, and I’m saying,

You better get your ass back on that plane and get out of there. What’s happening here?

The negotiations continue. Thirty minutes drop down. I talk to Shali again,How are you coming?

He says,They think they’ve got a deal. Just hold on; give me the other 30 minutes.

I say,

You’ve got it.

It was pretty tight. I was really very concerned because now I have the Navy Seals already loaded in their boats, engines running. They need to be released in about the next 30 minutes in order to keep the matrix going. Then I get a phone call of a sudden from Shali; I think I have about 10 minutes to go. He says,Okay, they have a deal. Turn it around. I’ll tell you what your mission is in just a minute.

I turn to Frank Akers and say,

Put the word out.

We had a code word for that.Put the word out and make everybody acknowledge receipt.

They do. Then Shali tells me,Okay, you still have to go in tomorrow, but go in in a spirit of coordination and cooperation.

I said,What does that mean in military terms?

He said,Coordination and cooperation. Get a hold of [Raoul] Cedras when you get in there, set the rules, and just do what you have to.

The 82nd had been the primary; General David Meade, the Commander of the 10th Mountain Division, was the backup. Fortunately, I had the foresight to put him on the Mt. Whitney with me, just in case something like this happened. His troops, 10th Mountain Division, were on the [Dwight D.] Eisenhower—the aircraft carrier we used other than the America—and ready to go in.

I said,

Okay, Frank, Dave—I called the J-3, Dan McNeil—let’s go back here in the conference room.

Bradley Graham trailed along. I walked in and said,Okay, here’s what we have to do. Dave, tomorrow, we’re going to put your people in by helicopter. I’m going to go ahead and put the Marines into Camp Haitian as we planned. You’re going to go into Port-au-Prince, and you’re going to go to the same sites the 82nd had identified as targets. You make a plan to do that. Again, your role there is to just watch what the Haitians are doing. Make sure your troops understand: no shooting, only in self defense. You go to the same targets and keep us informed about what’s going on there. I’ll land early on, same time you do, at Port-au-Prince. I’ll go directly to Cedras’ office and establish the ground rules.

Here’s what I’m going to tell him: ‘As established and agreed to by you—’ this is where negotiating comes in— ‘here’s the way it’s going to work. I’m here in a spirit of cooperation and coordination, and the way it works, General Cedras, is I will coordinate with you as long as you cooperate. You basically are going to do what I tell you, and if you don’t, this will become a hostile environment very quickly, and your people are going to die in mass numbers. Do you understand?’

He will understand; he did.I said,

Those are the ground rules, okay? Only shoot in self defense. As soon as I’ve had my meeting with Cedras, I’ll get back to you and tell you what to anticipate.

That was it.Dave Meade took off to go back. We’d already done some vignettes as part of the training for the 10th Mountain division about how to go into an area and monitor and supervise as well as fight. The troops today in the Army are very smart, very articulate. They can pick up on it in a hurry, and they did. So that was the end.

I went back, and my Chief of Staff, Frank Akers, was sitting there. I turned to Frank—Bradley Graham was still observing all this—and said,

Well, Frank, it’s been a great career. I’m now the bag man. When this thing goes south on us, they have me to blame, and I accept that. That’s what I signed up for. But I’ve been handed ten pounds of shit in a five pound bag (if you’ll pardon my French). This is what we have.

I really thought that was the end of my career. I never anticipated I’d be able to pull this thing off and have it as relatively bloodless as it turned out to be.The next day I landed. There were about 450 media there on the airfield, in a mob. Later on, Bradley Graham told me he was embarrassed by his cohorts from the media as I landed with my protection crew, a group of Navy Seals, well trained in how to take care of people. The Seals basically shoved them aside and made an alleyway for me to get through as they were trying to cram mikes in my face and get a shot. It was rough.

We finally got into Port-au-Prince airport, where I met with General Jerry Bates, an Army two-star who had gone in with Powell and that crew. He stayed behind to brief me on what had come out in the meeting, which was good planning. Ambassador Bill Swing, a North Carolinian, was there. I just had time to shake hands with him and tell him and Bates what I planned to do after they briefed me, and we went straight—

Riley

What did they tell you, basically, about what—?

Shelton

Basically that Cedras and [Michel-Joseph] François, the police chief, and [Emile] Jonassaint had agreed that they would allow the U.S. forces to come in, and over a period of time, they would agree that President [Jean-Bertrand] Aristide could come back, that time still to be determined. My forces would be there in the spirit of cooperation and coordination, just to make sure that the Haitian people were not treated poorly in the interim before Aristide could be brought back.

So we did that. I went in and met with General Cedras and laid out for him what I just explained were my conditions of cooperation and coordination.

Riley

You had been briefed previously, I guess, on Cedras himself?

Shelton

Oh, yes.

Riley

So you knew what to expect.

Shelton

I knew backgrounds on all the key people. I knew the guy standing on the Port-au-Prince airfield to defend it. I knew his rank, his name, his background. I left out that part. As I landed at the Port-au-Prince airfield, the Commander of the airfield, a Haitian, came to meet me, saluted, stuck out his hand. As we walked away from him, I carried with me my plans officer, Bert [William B.] Garrett—along with my lawyer, by the way—as I went in. Garrett said to me,

General, that Colonel doesn’t know right now that he’s the luckiest man in the world.

One of the predetermined targets that we weren’t going to ask questions about—we were just going to kill them as we went in—was a particular building. There was about a 25-man security force for the airfield that stayed in that building on that airfield, and there an Air Force C-130, a Special Ops bird with a 105 Howitzer that’s deadly accurate, was going to explode. That building was going to be blown to smithereens and all of them inside would die. We wanted no resistance for those paratroopers coming in.We also were going to hand Special Ops over to take over the palace. There was a very well-maintained and active crew with one of the air defense guns that sat in front of the palace. They kept two guys on that who normally were asleep during the night; one slept on the ground, one slept on the gun, but they were not active. We were going to take out that gun. Those were the two targets that were going to be hit first and simultaneously.

Riley

Okay, so we got you to Cedras. Was he what you expected when you met him?

Shelton

Yes, he was. He looked every bit military, very slim, a very fit-looking guy. He was, I could tell, somewhat nervous about this meeting. We met, we had pleasantries. I introduced myself. I was very stern. There’s no smiling with the guy. I wanted him to know I was 100% business. We sat across the table from one another. He had all of his thugs, all of his assistants, lined up beside him there. I carried with me a native Haitian, whose parents had lived right there near Cedras’ headquarters, [Major] Tony Ladouceur. He spoke fluent Haitian as a native, of course. He was my translator. Cedras understood some English. He told me that right up front. Very little. He preferred to speak in his native language.

Riley

Sure.

Shelton

I outlined the rules with Cedras, and he looked at me. There was a moment of a very stern stare between the two of us. He had just heard what I said, and he reached down—he took very meticulous notes, and he had very fine hand-printing—and he started writing. He looked back up at me and said,

Okay.

I knew I had him. The negotiating was over. The course had worked. Set the needle all the way to the right. If the guy wants to negotiate, then you’ve got some wiggle room to come back a little bit, to maybe move more towards the center. It’s just like buying a car: bid a thousand dollars below what you think he’ll sell it for.At any rate, it worked. I warned him at the time,

I have well-trained and well-armed troops here, and we’re anticipating you’re going to get the word out.

He said okay. I said,Whether or not you carry it out will be evident from the manners I observe from your troops. I’m anticipating that this word will get out to them very quickly.

He said,It will.

So I left General Cedras and got the word out to my commanders:

Here’s what we agreed to and here are the conditions, but I want you to stay armed and ready. Wear your protective vests, wear your helmets, keep your weapons at the ready throughout this period. I want them to know we’re 100% business.