Transcript

Martin

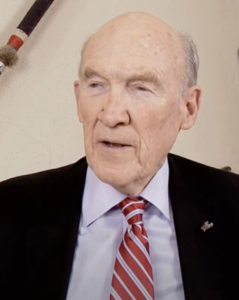

This is Paul Martin; I’m here with Alan Simpson. We’re in Washington, D.C., March 2008. He is here to talk with us about his experiences as a Senator during the Clinton administration. I want to start with the question of the 1992 campaign. Were you actively involved in that campaign?

Simpson

First, I knew Bill Clinton when he would come to Washington with issues that confronted the Governors.

Martin

Okay.

Simpson

He would roar into town—there were a couple of times with his group of Democrat or Republican Governors, at the Governors’ conference—when he’d contact us and say,

Hey, we need this for education,

orWe need that,

and so on. Then, of course, some of my and my wife’s best personal friends were David and Barbara Pryor, so we asked,Who is this guy? Who is this guy Clinton?

Oh boy, they filled us in, because they were intimately aware of Bill and Hillary [Clinton]. Then, of course, Dale Bumpers was a great pal of mine; we loved to trade great stories. He told me a lot about the Clintons, so he was not an unknown to us.Then came the campaign of ’92. Of course, I’d known George [H. W.] Bush since 1962. My father came to the U.S. Senate in ’62 and took over the actual physical office of Prescott Bush, who was George’s father. I met George there as he was bidding his father adieu and I was getting my Dad settled. Later my folks sold their home in Washington to the Bushes, Barbara and George, when he was elected to Congress—I won’t romance along on all that—so I was obviously very active in the campaign for Bush, exceedingly active.

Martin

Were you involved with strategy?

Simpson

That’s not my bag. I’m a legislator. I love to legislate. Plotting, strategizing, philosophizing, those things mean nothing to me. I’m a trigger guy. Give me an issue; let me wrench the emotion, fear, guilt, and racism out of it and get some facts into it and see if we can pass the son-of-a-bitch, whether it’s immigration or veterans’ benefits or Social Security or nuclear high-level waste. Those were my issues, all of them raised or lowered on the standard of emotion, fear, guilt, or racism, so I wasn’t part of the

inner circle

!I campaigned when George would call, or my friend old [James A.] Baker [III], who was often handling George’s campaign. They might say,

Meet us in Billings,

orCome to Florida,

or whatever, and I’d go. George is a very dear friend.I did tell him that I thought it was very important that he stay away from the Cigarette boat (a racing water craft) during the campaign, and the golf course, and Jim Baker told him,

At the Democratic convention, they’re playing music that you and I don’t even know

—Fleetwood Mac or whatever it was. That was a Cadillac car to George and to me. We’re old farts.It was an unfortunate campaign, I thought, to portray George Bush as a man out of touch or lost in the swamp or not paying attention. But so it came to pass. I was active in the campaign, mostly campaign events on the road or meeting him as he got off the plane and wherever we were, introducing him sometimes.

Martin

Do you remember what your sense was about Clinton as an early contender? Was he on the map of folks against whom Bush expected to run, or was he predicted in any way?

Simpson

No. Everybody else had quit. There are still guys wringing their hands in the Democratic Party because they didn’t have the guts to step forward. I won’t name them, but there are at least four or five. They would opine,

I’m not going to run against Bush. My God, he’s the most popular guy we’ve ever had. Why throw myself on the fire?

Clinton did. I don’t think they realized the intensity of how he would gather the troops. But you want to remember always that people don’t vote for; they vote against. I don’t think anyone won an election because people were for them; they voted against the other guy. That may sound insipid, but it is the way it is.My father was a Governor and U.S. Senator. When he was Governor, he was beaten for re-election because he was not in favor of capital punishment, and there were other things that he had done. After the election, Annie [Simpson’s wife] and I were in a Greybull, Wyoming restaurant booth and there were two guys behind us and one said,

Well, we got rid of that son-of-a-bitch Simpson, didn’t we?

The other said,Yeah, and who did we get?

and the first guy said,Who cares?

That’s where Bush was in that election. Then came Ross Perot. We tried to talk him out of it. I called him and said,Why are you doing this, Ross?

[imitating Perot’s speaking style]George lied to me twice. That’s what he did; he lied to me. I then know he did.

I went back to George and said,

He’s not going to get out.

George said,Why not? Well, I guess that’s it.

I said,Why don’t

you

go talk to him?

George said,He lied to me twice.

I never found out what the two lies were that crossed each other, but one of them was when Perot went to Vietnam. George had said now don’t get involved in any prisoner exchange or try to bring anybody back and then Perot did. That embarrassed George. I don’t know the other one.Don’t forget, old Bill Clinton never got more than 50 percent in either election!

Martin

Yes, 43 percent in the first election.

Simpson

What was the second one, 47 percent?

Martin

Something like that. He got more, but he didn’t hit 50 percent.

Simpson

So it was that Perot thing, the Clinton ascendancy, [Albert] Gore [Jr.], the magic, the charisma—just what’s happening today, in this election. They’re tired of the Bushes and they’re tired of the Clintons. There’s something going on like that. I didn’t come here to be partisan; I just see it. There’s a fatigue factor that has to do with no more Bushes or their coterie or any more Clintons. The voting, I think a lot of it, for [Barack] Obama is just, you know, against Hillary.

Martin

We do have a long history of having both fascination with political families and then not liking dynasties or inherited political clout.

Simpson

I didn’t answer your question at all, did I?

Martin

No, but it was a good answer to a different question. [laughing] Let me follow up on a point that you did raise, which was the sense that Ross Perot ran as a personal attack against George Bush, senior, to personally upset Bush’s reelection.

Simpson

I believe that. I don’t know the reasons, because Perot never told me. I had said to George,

Do you want me to call Perot?

I think Bob [Dole] may have done it too. I said,I’ll call him.

I did. I spent about 20 or 30 minutes. I’d met him before. [imitating Perot again]Well, you know, got to do it. Nobody is going to lift the old hood.

He had all those phrases:lift the lid,

what’s under there,

let’s get that engine going again.

He just said to me,No, I’m not going to get out.

I think there was an antipathy there. They were Texans. They’d been in some business activities. I’m sure there were hundreds of opportunities for their relationship to go awry, and it did. Damned if I know what it was. But he surely defeated Bush—27 percent of the people in Maine voted for Perot and Wyoming was second, with 25 percent voting for Perot, and he got 20 percent across the nation. Those are big numbers.Martin

You write in your book that when the election came in 1992 you and most other folks knew that Bush was going to lose.

Simpson

I thought he was going to lose if he continued to look

out of touch,

because he wasn’t out of touch. The worst one was when he was in that grocery store where they took a receipt and put it on this screen and he looked at it and said,Well, that is amazing.

Well, it was amazing, because the guy had torn the receipt in five pieces and then put it on there and it rescrambled it correctly. That’s what he saw, but the media reported it as,Well, there’s dear old George, out of touch, doesn’t know the price of a quart of milk and not even how this new checkout system works.

Martin

Scanner technology.

Simpson

George said,

Al, if you’d seen it, you’d have said, ‘My God, that’s fantastic,’ because he tore the damn thing in five or six pieces and dropped it on there and it actually physically scrambled it into a readable format.

There was a lot of stuff like thatout there

on George.Of course, there was some internal struggle within his organization. [John] Sununu was just saying,

We’ll

finesse

the issue of the economy.

Senator John Chafee and I said,You can’t finesse the economy, for Pete’s sake.

[laughing] Sununu was irritated with that. Then Michael Boskin came in one day to Sununu and said,I’m having a press conference Wednesday.

Sununu said,What about?

He said,I’m resigning.

He said,You can’t do that; you’re the economic guru.

Michael said,Yes, I am. Unless I can see the President, I’m resigning.

Sununu said,Oh well, we’ll take care of that.

He finally got in and he told George,The economy is sluggish right now, but there’s going to be a run of about eight or nine years. It’s going to be a big run, too, and you ought to be telling people that. Don’t tell them everything is good now, because it isn’t. Tell them that what I see in my work with all my people is that there’s this sluggishness now and then—bam.

The Clinton people will say that it was Clinton’s badge to wear, but that’s what other economists were saying too. But it wasn’t getting across. Then they hit on the beautiful quote in there,

It’s the economy, stupid.

I know old Jimmy [James] Carville fairly well. He and I have done some shticks together. He is fascinating. He’s fun and he’s good and he’s tough. Anyway, that doesn’t have a damn thing to do with anything, except it was a campaign where I knew that if he, George Bush, was seen as not paying attention or missing the boat it would be tough—and then cameread my lips

!Hell,

read my lips

could have been a badge of courage. Certain Congresspersons went out to Andrews Air [Force] Base and put together some real budget reform, two-year budgeting—got rid of things that were hanging like barnacles on the whole economicship

of America (entitlements, Social Security.) Democrats and Republicans alike worked on it. Bush agreed and knew he would be hit hard—but not if we all stuck together. Dole kept coming back after negotiating and telling us. He said,Now we will have to go for this.

The Senate voted 68 to whatever; and it went to the House. All you have to know is who did what to whom. Just look at the roll call vote in the House, as Henry Waxman, Newt Gingrich, [Howard] Berman, Pete Stark, and [Richard] Armey all voted together to kill it. Take a hard look at that roll call vote.Martin

That’s an unusual vote, to have those folks together.

Simpson

And it really pisses some conservative people off when I bring that up. We lost all of the structural budget reform and then

they

came back with a tepid bill, while we lost the two-year budgeting, lost this and lost that. Some good things were done. Bush had said,I’ll do it [reject ‘read my lips’]

only

if we can keep this package and our party together,

so it then became all aboutread my lips,

and that was a disaster.Then many of the [Ronald] Reagan people didn’t help Bush. They were a little irritated at him for various reasons. Reagan himself wasn’t, but some of the Reagan people were there, waiting for their people to get into power again under Bush. They didn’t. In George Bush’s first term, they’d come in to me and say,

I was Ambassador

to so-and-so.I haven’t finished my work. I was doing God’s work, and, Jesus, he’s replaced me.

I’d say,Yes, he probably did. He’s the new President and he doesn’t give a rat’s ass whether you served Reagan for however long you’ve done it.

Those people never got over that.Martin

Did they not come to support Bush in ’92?

Simpson

No, many of them didn’t, because Bush wanted his own people. If you don’t understand that in politics, you’re a pinhead. Other than that—We haven’t gotten to Clinton yet.

Martin

So Clinton started with only 43 percent of the electorate, and there’s a lot of speculation within political science about how that reduced vote affected the entry of his Presidency. Was there a sense on Capitol Hill, or in the Senate, that he’s a minority President and we don’t necessarily have to go along with him?

Simpson

I didn’t sense that at all because of his remarkable—overused word—

charisma.

He had a persona. He’s real. When he came into a room and started to chuckle with you or tell a joke, it was not affected, it was real. He loved people.He came to town—the most interesting little thing with the Clintons—as I say, I didn’t know him well. He knew that I knew him because of Senators Bumpers and Pryor. Imagine, on inauguration day, Dole was up on the front platform, with the 200,000 plus out front; and out the back, I, as assistant leader of

the other faith,

and Ann were taking George and Barbara down the east Capitol steps to their chopper waiting there. Ann and I brought George and Barbara down those back steps and Hillary [Clinton] and Bill got out of the big black limo to go up the steps. In just a few minutes, he would be President of the United States. Fascinating little foursome we were—a trip I shall never forget.So down the stairs with George and Barbara and we gave them a big hug and a kiss; off they went. Here came Clinton and Hillary walking up the back steps. I said,

Congratulations.

He said,Senator Simpson, I know all about you.

I said,What do you know?

He said,Bumpers told me all about you.

I said,What did he say?

He said,You’d tell me a lot of funny stories and then you’d stick it up my ass.

[laughing] Hillary put her hand out and said,Bill, stop it. Ann, I know all about you. Barbara Pryor has told me all about you. She considers you one of her nicest friends. You and Al will be in the White House among the first people—within the first couple of weeks—once we get moved in. I want to get to know you better.

A little more banter took place. I said,I’ll tear Bumpers’ leg off when I see him

and all that chatter that goes with a couple of old pols [politicians]. Then he went out there to sit there on the front platform and he was soon the President of the United States.About two weeks, three weeks later, we were invited to the White House. I don’t remember what it was; it wasn’t a large group, maybe fifty, forty. I watched Hillary as she began to visit with Ann. Hillary never turns her head when she’s talking to someone. She is absolutely riveted. She doesn’t look around like,

Oh, hi there, Tilly; how are you?

—or divert her attention from the person she’s talking to. That’s a gift. You have to have that in politics. There were people around—it was adulation:We want to talk to Hillary.

She must have spent about fifteen or twenty minutes with Ann on mental health issues. Ann was very active with Tipper Gore and Sheila Wellstone and Nancy Domenici. The four of them worked hard on that. Anyway, I thought that was fascinating.Of course, in that first spring—the idyllic spring, when you are the most popular person on earth and the world is your oyster and that’s the way that is, it doesn’t matter who would be President—so we were at an Oriole game. I knew an owner of the Orioles—Eli Jacobs, who was an old friend and Republican fundraiser for me, and he was part owner of the Orioles—and Bill was there. We sat next to each other. He said,

You got any tips, Al? You’ve been around.

I said,Yes, I’ve got a tip for you, a real one. Don’t miss it, because your staff won’t remember it, that’s for sure. Go see Robert Byrd [Majority Leader]. Just go to his office. Don’t ask your crew to tell Byrd to drop by the White House.

You

go to Byrd’s office and pay your respects. That will gather you dividends that you can never imagine.

He said,Hell, I’ve met Byrd, I’ll do that.

Then we bantered around, told some jokes.He loves jokes. We both love ribald jokes, not the kind you can share. He went to see Byrd. I was assistant Republican leader, so I would see Bill from time to time from then on until I was defeated for assistant leader in ’94. I had two years with Bill Clinton and was often in the White House.

Martin

Your story brings up two things that are reported about Clinton during this period, especially the early period, the first of which is that he wasn’t very good on the social aspect of being President, and that the Washington community felt somewhat rejected by him or alienated by him. But your story sounds opposite to that; it sounds like he knew what he was doing socially.

Simpson

Damn well he did. That view would be the myth of the century. This is not name-dropping now, but Kay Graham became a very lovely friend of ours. We were often invited to her home. She would even invite us up to her home on the Cape. We never went, because I didn’t want it reported in the Washington Post, and because it wouldn’t look good in the Casper [Wyoming] Star-Tribune. But Kay would come up to Ann and say,

What is he doing now? What is Alan doing? How the

hell

did he get tangled up in—?

Ann would say,Don’t ask me; I don’t run his life.

Then one day we had a seminar or something at the National Press Club and it was about the media. Kay said,

You bastard, you’re just terrible to us.

I said,Well, somebody has to be. The first amendment belongs to me too.

She was gracious and broad enough a person to accept people of all stripes. They miss her here, not because she had nice parties, but because she took people with diverse views and put them in the same room for drinks and dinner and discussion and questions. You’ve read about her. She was a shy person, but she was marvelous.Anyway, we were invited to a small dinner at Kay’s with Bill Clinton. Hillary was not there. It was early, January or February, after the election—I don’t know why I couldn’t go, but I was assistant leader. I was running the shop and it was a night event—I don’t remember, but Ann went. Of course, Bill had met Ann; he knew Ann, not well, but he knew her. She came home and said,

That man was impressive. He spoke after dinner. Kay introduced him. He was charming and impressive and knew the issues and knew the facts and remembered people’s names. He was good.

That’s the way he is, to this day.Martin

I always thought that that allegation didn’t seem like it fit with his personality or his persona. But he did get hit quite badly by some of the early reports out of that administration, that he alienated Washington society.

Simpson

He may have declined invitations. I don’t know what he did, but he sure as hell didn’t decline anything Kay Graham threw out. I never did either, because I always knew I’d be in a room with some guy I didn’t agree with totally—some

commie bastard.

[laughing] It would give a new level of understanding with that person. I didn’t have to agree with their lifestyle or their philosophy. That meant nothing to me, and still doesn’t. That’s how I get in a lot of trouble.Martin

What about the beginning? Let’s go to after the transition, after the inauguration. Can you give us a sense of how Clinton was being viewed, by both the Senate more broadly, but also by your Republican colleagues, or the leadership of the Republicans in the Senate? Clinton had a lot of stumbles, and many of them had to do with his interactions with the Senate. My sense is that if there were going to be any concern about this new President, it would be more from the Senate than from the House.

Simpson

I think the Republicans finally could see that this guy was real and he was formidable. Any time you get that view in the minority party, they try to figure a way to shackle the racehorse. There were guys in our caucus who suddenly started to say,

We have the President’s budget, and there’s stuff in here about playgrounds.

I can remember that they would pick out something filled with emotion, fear, guilt, or racism that doesn’t mean a rat’s ass in the whole scope of human endeavor, but it’s a trigger point. They were beginning to dig those out on Clinton in order to embarrass him. That always went on. It went on when Bush came; it’s a common thing.But he had that wonderful guy who had been David Pryor’s AA [administrative assistant] and went then to Bill, Bruce [Lindsey]. He would have fallen on his sword for Bill Clinton. He would have died for him. He was always out of the media. I used to see him. I’d say,

How you doing, pal?

He never lost his balance or anything, but he was an amazing gyroscope. He’d feed all that

stuff

out to Pryor and Bumpers, who were always ready to help on the floor. He couldn’t have had any better allies, although at one time they were sometimes adversaries, since all three of them were Governors.Oddly enough, when Bumpers retired, he asked me to emcee his retirement dinner and the two main guests were Clinton and Pryor. Imagine that evening. You ought to get a recording of that one, because it was a hell of a lot of fun. Clinton said to me,

God! I can’t thank Al enough for screwing me.

[laughing] Anyway we had a lot of fun. Bumpers and Pryor told stories about Bill when they were all young politicos in Arkansas. But anyway, they were always there on the floor to fiercely help him.When my father died, my brother and I were sitting in our kitchen in Cody. It was ’95. The phone rang at 12:00 midnight, Wyoming time—2:00 here (D.C.) It was Clinton.

Hey, Al, very sorry about your dad.

I said,Brother Pete [Simpson] is here.

He’d met Pete. He told Pete,How are you? Sorry about your dad,

and he talked. He loves to talk. I said,It’s 2 o’clock in the morning out there.

He said,I know, but I was just thinking of you.

Then he said,

I hope I will always have a friend in this business as close as you were to George Bush.

I said,You do; you have Vernon [Jordan], Bumpers, and David Pryor.

He didn’t say that they weren’t there, but he was—I don’t know what he was saying. It was very pleasing to me. I said,Well, you do have them.

Certainly Vernon who became, and is, a very dear friend, and Pryor and Bumpers—I love them. So he wasn’t drawing a distinction; he was expressing the need saying: I have to have people like you or I can’t make it. They hadn’t been able to be proved by fire yet. They were. Especially Vernon and Dave and Dale.I remember Dale got in trouble once emceeing a banquet for Hillary and Bill. I won’t go into that one!

Martin

Your stories suggest that Clinton clearly reached out to you.

Simpson

Well, I was assistant Republican leader. He liked Dole, but Dole is just a special guy. I would go over any hill for him into full fire—as his lieutenant, and I was in the Army too. He was the captain and I was the first lieutenant, and that’s the way we ran it. I never wanted to run for his job, but Dole loved the politics—Dole is not a social animal and eager to go into Kay Graham’s home and sit around all night at some function. That wasn’t Bob Dole. He’d like to get on the phone to find out if there was a primary election in the 13th district of Timbuktu. That was what he loved; that was the way he worked.

Dole is not in any way, and I say this carefully—there is no real profanity in the life of Bob Dole. I cursed for him! I took that role upon myself, because Bob is real—He’s moral; he’s shy, in a way. He is filled with good humor—sometimes misread, but always who he is—but not a guy who’d say,

Hey, I have a new one for you.

That was never part of Bob. I always stayed away from that with him. I’d stand right next to him and he’d say,Oh my God, Simpson’s got another one; go tell them, Al.

So I would.I guess that once the earthy humor started between Bill and me, he knew I wasn’t out to screw him, and if I was, I was coming straight ahead like a freight train with the headlight on. I remember one White House session in which he said,

I can pledge this early on, we’re going to do something with Social Security and the entitlements.

God, it was a beautiful talk, in the Cabinet Room, around the table.What about you, Al? What are you thinking?

I said,Look, you don’t have a prayer as long as you can’t muzzle the goddamned AARP [American Association of Retired Persons] and the Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, and others, those hysterical monsters will cremate any kind of reform you’re doing, so you’d better get them in here first. If you can get them in here—and they may not come, but get them in—and you’ll find out what you’re facing.

He said,I’ll do that.

He did and then he found out where the crematorium was erected. These bastards are the most selfish of people. They don’t care about their grandchildren. Their legislative agenda is that thick, two inches. It’s all about more money for seniors—no means testing, no affluence testing. Monsters.

I would tell him those things. I would say,

Good talk, but you’ll never get anywhere.

Or something would come up with education. I’d say,You’d better get the NEA [National Education Association] in the room; or they’ll eat your lunch like cookies. They’ve torn through more Presidents than you.

Or sometimes I’d just say,I’ll tell you what they’re plotting on you.

He’d say,They’re not going to get away with that.

I’d say,Well, maybe they won’t, but they’re going to try.

Martin

Do you have a sense that he had much of a relationship with other Republican Senators at this period?

Simpson

I don’t know. I think that he and Dole had one—Dole was the leader.

Martin

He had a reportedly brusque relationship with even people in charge, [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan, for example. Not a great relationship there.

Simpson

Well, Moynihan was tough to know. I got to know him well. I’m not lauding myself. I liked Moynihan; I loved his wit. He could quote poetry and so could I. He was an amazing intellect and yet could get things across—I mean, when you’re from Hell’s Kitchen in New York City, and you’re raised there in the slums, and come up as an erudite, intelligent, brilliant man—that intimidated a lot of people. I was very intimidated by it at first. We had a couple of visits one late night session where we laughed our asses off and recited

The Cremation of Sam McGee

and Shakespeare and a little bit of Longfellow.I think Bill was a little awed by Washington. He suddenly realized he was the President of the United States and Who are these people? He knew one thing: his greatest skill was to get to know people and get them to go his way.

Martin

I’m thinking about some of the characters who were Senators at this period. They were older than Clinton, some of them much older than Clinton. How much did that age difference affect his ability to connect with Senators?

Simpson

I never equated it to an age factor. We’d go to the White House, and he had people at the White House quite often. Of course, again, I was assistant leader, so sometimes Dole couldn’t go and I’d go. [Mark] Hatfield was still there; Russell Long went out in the late ’80s; [Charles] Mac Mathias [Jr.]—He liked Mathias. He and Mathias had a good relationship, but Mathias was, as Strom [Thurmond] said [imitating Thurmond’s Southern drawl],

Gotta watch Mathias.

I said,Who?

He said,Mah-thaw-ahs.

I said,Who are you speaking of?

He said,He’s very liberal, Alan, very liberal. Got to watch him like a hawk.

But Strom liked Mathias. There was Lowell Weicker. We had a modest and robust number of moderates who were heavy—like [John] Chafee—on environmental issues. Bill knew that Jesse Helms wasn’t going to lock his arms around him, but even with Jesse you have to try. You’d ask Jesse what his thoughts were about Bill.I guess he’s okay.

But there were guys in our caucus who were always just out to screw Bill—in the latter part, while I was assistant leader, it became absolutely tedious, because they would be talking all during the caucus about how to craft a piece of legislation that would blow up under Bill Clinton’s nose.

When he gets this, he’ll have to veto it,

orHe’ll have to do this.

It would waste a half hour of every caucus. Finally, I said,I just want to tell you something. Give it up. You’re not going to trick Clinton. In fact, you remind me of the damn roadrunner in that old cartoon. You make a bomb and you roll the bomb down to the White House and old Clinton will pick it up with the fuse burning and roll the son-of-a-bitch right back and it will blow up under your face

—like with that red-headed guy with the whiskers.Martin

Wile E. Coyote.

Simpson

You’ll have black powder all over you,

I said.That’s what Clinton will do to you. Give it up. If he doesn’t do it, his people will do it. They have all of you figured out; we’re wasting our time.

I don’t know if that ever got back to him; it doesn’t matter. But that pissed some of our crew off, and they’d say,It’s our duty to screw him.

I’d tell them,The country has to run; you came here as legislators, not as bomb throwers.

Martin

Is it fair to say that there was conflict within the caucus between people who think of themselves as primarily legislators and people who are more political?

Simpson

Oh yes, sure. Here’s the definition of politics.

I’ll give you tickets to any game,

I told my students at Harvard,if you can tell me anybody who said this but me; start searching.

I don’t know where or when it came to me, but here it is, it’s very short:In politics there are no right answers, only a continuing flow of compromises among groups resulting in a changing, cloudy, and ambiguous series of public decisions—where appetite and ambition compete openly with knowledge and wisdom.

There’s no more to it. If you can think of any other definition, forget it. Changing, cloudy, and ambiguous—appetite and ambition—knowledge and wisdom, that’s all it is. You have the show horses and the workhorses. The guys who, if they see a TV camera light, are like a giant moth, they go to it just to babble into the vapors, versus some guy who doesn’t give a shit about that and is ready to do another hearing so he can get together enough amendments to get a bill passed.Martin

At this time you were able to put together a pretty strongly united Republican Party within the Senate.

Simpson

Yes.

Martin

You had 42 or 43 people sign on to a series of

Dear Colleague

letters to Dole, basically saying that they were going to back whatever he did, at least on the economic policy front. How did you get everybody together on something as big as economic policy?Simpson

That’s very easy. They wanted to be back in the majority. In the caucus you could say,

You sons of bitches, you want to be back? You want to get back in the big room over there? You could be in the Mansfield Room for lunch instead of over here.

[laughing]You want to have more staff again with more money? Want to be the chairman? Then there’s only one way, one way

only

: stick together. If you don’t stick together, we’ll never get back in the majority.

It’s a very simple pitch. Works just as well with Democrats as it does with Republicans; it’s calledI want to get back in the majority.

The only way to do that is to stick together like adhesive. There’s no mystery. It wouldn’t matter who the President was, either. It wouldn’t matter what was going on, either.Martin

Somebody I interviewed earlier said that budgets are partisan documents, so it would be very rare to have a bipartisan budget come through. In ’93, ’94, and ’95, most of those budgets came down to party-line votes for both the House and the Senate. Is that a fair assessment of those documents?

Simpson

I believe that all throughout the times I remember a budget would be prepared—and the chairman, whoever it was, of the other party would say,

Well, nice try, but it’s D.O.A. [dead on arrival].

What’s new? That’s the first retort. Great idea; we know they worked hard on it up there, but it’s dead over here! Why? It’s all fiction. All budgets are fiction, total fiction. There isn’t really anything in a budget—they project growth and percentage of CPI [Consumer Price Index], and real growth and on and on and on. It’s just babble; it’s bullshit. Of course it is now completely out of the realm of human grasp, the talk of trillions. Nobody knows what a trillion is.Martin

So when Clinton put together his economic policies, both the stimulus package that fell apart in April ’93 and the budget reconciliation that went back to conference in August of ’93, the Democrats voted basically for it, with the exception of David Boren and a few other Democrats, and the Republicans collectively voted against it. There’s a logic, though, that says, Why not give Clinton what he wants, because if it doesn’t work, it’s his fault, and if it works, we went along with it. Folks don’t make that calculation?

Simpson

No, because you can pick anything out of the budget. As I say, I remember there was something about playgrounds or something about tax districts that was absolutely stupefying. It was a trigger for us.

Oh man,

I said.Clinton’s for this?

One was inner-city lighted basketball courts.Martin

Midnight basketball

? That was definitely one of the triggers.Simpson

You’re kidding. You remember it? Because that’s exactly what it was.

Martin

I don’t know the details of it. I just remember that it was one of the big triggers that people would talk about.

Simpson

What a terrible thing for Clinton to do, he and his minions! But you see, that’s the absurdity of it all. It was just time to stick it to Clinton, because he was getting his way too much. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a college president or whatever, if you get your way too much, you’re in peril.

Martin

What about the folks who were—presumably if they were in politics then, they probably would be closer to the average voter for Democrats than Republicans, like John Chafee? Why did they stay with the Republican Party versus—There was lots of legislation that Clinton was pushing through in this early period. People assumed he’d be able to peel off [David] Durenberger or [Robert] Packwood or Chafee or a few of the folks on the more moderate-to-liberal side of the Republican Party, but through this period they stuck with the Republican Party.

Simpson

Why not? They were in a caucus where ten other guys would get up and say,

You son-of-a-bitch, you stick with us this time or, by God, we’ll be in the minority forever! Unless you get off your ass and just give us this one vote.

Now Dole would never do it that way, but the hard-liners, they’d say,Don’t you want to be chairman again? You love wandering in the swamp around here? That’s all you need to do; it doesn’t have a damn thing to do with anything.

Chafee, Mathias, Packwood, Weicker, and all of them would occasionally go their own way, but they had to be careful, not because they were not people of great character, but because who likes to have someone chewing on your legs all day long. So when they would stray, instead of having a caucus vote about punishing them, others would say,Oh hell, they have to go do that every once in a while.

And they would. Dole knew that; I knew that.Martin

What could the caucus do to punish them, other than give them a hard time?

Simpson

Well, the best thing would be to go out on the floor and say,

We’re very disappointed in our colleagues,

thus starting the schism that would destroy unity—not ever giving you the ability to get back into the majority.Martin

It wouldn’t be denying a chairmanship or a committee or something that extreme?

Simpson

There was only one real hard charger, I recall. I’ll tell you who it was. Rick Santorum came into the Senate. He was a firebrand. I couldn’t handle him. I said,

Don’t mess with me.

I was pro-choice and he was on me about baby killing and fetus murder and everything else. I said,I don’t need to listen to that shit from you.

So then came so-called partial-birth abortion. That’s a doctor’s issue—a medical issue—it doesn’t have anything to do with the political arena. It is a procedure that medical people perform, not politicians. I said,Leave it to the docs.

God almighty; that would get you in trouble.Anyway, Mark Hatfield would not vote for the balanced budget amendment. He said,

It’s a fiction.

Of course he was right, but, by God, we were all committed to the balanced budget amendment because that was what you had to do. I’m not being cynical. I voted for it, but thinking maybe it was the hope of hopes, but Mark wouldn’t. He said,I’ve been an appropriator. You guys will be the guys who will come in to us and break the budget. Every one of you guys will be right in there at the trough and talking about a balanced budget; that’s bullshit and you know it and I know it. So as your chairman—

He chaired the appropriations committee while dear John Stennis was in extremis, had lost his leg. Mark Hatfield, with great grace and humanity, managed the committee for John Stennis. Stennis trusted him implicitly and I think so did Clinton. I’m sure that that was during that time. Anyway, Hatfield wouldn’t go along. He said,No. That’s a fiction and you guys will be the first guys to break it.

Santorum went to the Senate floor and said it was disgraceful that a member of our party wouldn’t give us this controlling vote. It missed by one vote. I’ll tell you, Santorum never gained any more traction all through his time in the Senate. Remember, his last great one was that he said that homosexuals might also

do animals.

This guy was—well, he got eaten by rats in his final election. I’ve worked very closely with the gay-lesbian community; we’re all human beings, for the gods’ sake.Martin

In that early part of the Clinton administration, where he was not able to peel off some of the moderate-to-lefty Republicans of the period, you were explaining it was a desire to get back into the majority. How does that tension sit with folks who think more about legislation? At what point do you take a political vote versus thinking, This is a piece of policy that I actually care about?

Simpson

You’d have to ask those people. Ask the people who were involved in that; I can’t answer that. Just say there was always a great striving for unity so you could get back into the majority so you could do your agenda. One colleague said, when Reagan got elected—all of a sudden not all believed that Reagan would be the next President—and suddenly I’m the chairman of Veterans Affairs, and chair of the immigration sub-committee and chair of the nuclear regulation sub-committee, and this colleague said,

It’s like a football game. You carry the ball 98 yards, and then it falls out of your hands. Many Democrat hearts were broken.

[laughs] That’s the way you feel, that you came all the way down the field and then some son of a bitch came in and took your chairmanship and your staff. So the great urge is always to get back, not only so you can accumulate power but so you can work your issues, which no longer are the issues of the new chairman. There’s really not a lot of mystery to it.Martin

So for you, personally, you couldn’t do what you wanted to do on, say, something like immigration unless you were in the majority.

Simpson

I could, because I didn’t mind going to my pal and either chairman or ranking member Ted Kennedy and saying,

Look, why don’t we have a hearing on fraudulent marriage? That’s the fake of the ages, Ted.

He said,Yes, it is. Have a hearing, have your hearing.

I’d go to dear friend Jennings Randolph, who was the Democrat chairman of Environment and Public Works. I’d say,

Jennings, I want a hearing on predator control. Folks think we’re a bunch of coyote-killing sons of bitches in Wyoming and I’d like to tell them that coyotes are a bunch of sheep-killing bastards and there’s a difference here.

Jennings said,Run with it.

But that was because of trust and friendship. If that disappears—I always felt I could get my agenda up because I had a relationship with the other whips over my time: Alan Cranston and Wendell Ford. My three ranking members when I was chair of their committees were Alan Cranston, Gary Hart, and Ted Kennedy. I told them,

Look, you guys run for President; I won’t embarrass you, but don’t use this committee for your quest.

Shit, that’s easy to understand. You don’t need to be a wizard in politics or be [Niccolo] Machiavellian.Martin

That seems like a pretty fair deal.

Simpson

Yes, and they were all that way. They never used the committee for their quest. Ted would say we had to have a hearing on Ethiopia and the starving going on there and so on and I’d say,

Great, bring it up. I’ll have a hearing. You can do whatever you wish.

Martin

Did that change in ’94?

Simpson

I’ll tell you what happened, in my mind, with the Senate. The venom came from the House. I don’t care what party would control a legislative body for 40 years, but I’ll tell you, if it happened, whether Republicans in Wyoming or the Democrats wherever, it’s a cancer. These House Republicans were so pissed off, so frustrated. A Republican would put in an amendment and a majority staff guy would look at it and say,

I think our chairman will like that. We’ll take it and put his name on it and you’ll just have to do a different press release. So you go tell the folks back home how you screwed that up.

Shit, boy, nobody is going to take that for very long, so that person would leave. This was before they lost or gained the majority; they would leave and run for the Senate and bring the venom with them, saying that all Democrats are horses’ asses and that all Republicans are dumb shits. They’d bring it all with them, into this marvelous deliberative body. The venom came from the House.Martin

They would sit over there and stew, and then be elected to the Senate?

Simpson

Yes, and I could name them, from both sides of the aisle. They came from the crucible of partisanship into a deliberative body that hadn’t been infected by that for a long time. My dad was one of 33 Republican Senators—33?—and [Barry] Goldwater and [Everett] Dirksen and [Russell] Long and [John] Stennis—and they got along. They had dinner parties together and got along. Of course, you don’t have much power when you’re 33 out of a hundred!

Martin

Sure.

Simpson

But it’s tough to watch. Especially these days, [Orrin] Hatch and [Patrick] Leahy don’t talk together like they used to; I don’t know what happened to them. Anyway, enough of that.

Martin

At some point Clinton needed the Republican party to pass NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement]. This was his first major piece of policy where—at least in the House—it passed pretty much with the Republican Party’s vote and the Democrats let it go through with procedural votes, but very few supported the actual policy. Could you talk a little bit about how one turned a corner and went from, in August, the Republicans and the Democrats lining up to back and support Clinton on his economic policy, and then by September it all shifted for NAFTA. Would you still see that sort of shifting coalition today?

Simpson

You’re talking about a failure and then a success and the shifting of what to what?

Martin

The Republicans in the Senate at that period were 100 percent against Clinton on economic policy and then turned around and backed him on NAFTA. Is it just that the policies were different, so people liked the one policy, but didn’t like the other policy?

Simpson

No, it’s called getting smart—

Bruce Lindsey, that was his name. Do you know that name?

Martin

Yes. He’s on the board.

Simpson

Amazing guy. He was quietly a Gibraltar in the midst of the waves of crap that washed up on the shore. [laughing]

It was easy. By then the President and Bruce would say,

Aha, who do the Republicans respect over there in the Senate?

Guess who he gave the big task to? Lloyd Bentsen. Bill said,Now, Lloyd, I want you to get over there and work,

and Lloyd said,I’m going to appoint some deputies among the Republicans too.

I was one of Lloyd Bentsen’s deputies to get NAFTA passed. Without trade in Wyoming, we’d choke on our own product; there are only 500,000 of us. We’re the largest coal producer in the United States, oil, gas, petroleum, trona, MTBE [methyl tert-butyl ether]. If we didn’t export, we’d be the giant constipated lump in the middle of America. I was all for it.Lloyd would get us together.

Okay Simpson, who do you talk to today?

I’d say,I’ll talk to—

He had [Richard] Lugar and me and a lot of other thoughtful Republicans working the issue.Martin

It was a truly bipartisan operation?

Simpson

Totally, and that’s how he did that.

Martin

But Bentsen would have been leading an economic policy that failed—It passed in the end, but it didn’t get much Republican support.

Simpson

But they loved him and they respected him; they respected Lloyd Bentsen as a person, an old fighter pilot, a guy who admitted his mistakes. Remember, he had a fundraiser and found out that all these $10,000 guys were coming in to see him about the next day. The media said,

What do you have to say about that, Senator?

Lloyd said,When I make a mistake, it’s a doozy.

That was his remark and that was the end of it, instead of covering his ass. People and politicians loved that transparency and directness about him, so he was very popular. But he had people aligned with him from the beginning. There was Bentsen and then there was—I can’t remember; maybe it was Packwood. We had this small group of Republicans and meetings where we would say,Who have you seen this week? Where are they on this?

I don’t know what the final vote was. What was it?Martin

I don’t have it in my notes, but it passed. It was unpopular with the Democratic base.

Simpson

Well, they weren’t going to take on Lloyd Bentsen, who was a Vice Presidential candidate of his party in 1988. Any time one of the Senators would come back who had run for President of the United States—colleagues who had thrown themselves on the line—we respected those people; it didn’t matter what party. If you had the guts to run, because we didn’t—you were beaten and you came back and you went to work. He was an icon. I looked on him as a tremendous Senator and a great friend.

Martin

And he was a powerful voice within the Clinton administration on economic policy.

Simpson

That’s what killed him. He traveled all over the world with those heavy notebooks on his lap—not enough exercise—and he had an embolism in his heart, and then had a stroke. He was indefatigable; but he was in a plane all the time.

Martin

It’s hard on the body, that’s for sure. Can we push on to health care? We haven’t talked about health care and that’s the most significant policy fight, probably, of 1994. There were a number of policies floating around; Chafee had a policy. At some point there was some thought that Dole might have a significant policy; he’d been active on health care in the past. What was your sense about what went wrong there and why you didn’t see health care become legislation?

Simpson

You’re talking about Hillary’s?

Martin

Yes.

Simpson

That was the reason; history is clear on that one. It was too ambitious; it was too arcane. People didn’t understand it.

Martin

I want to follow up with another question about health care in ’94. You had mentioned that most of the problem was the process, that the Health Care Task Force was the problem.

Simpson

That was brutal.

Martin

One of the things that doesn’t make a lot of sense is that it stayed on the top of the agenda for as long as it did and didn’t seem to go anywhere. It was brought up in September or so of ’93 and they were working on it off and on all the way up until September of ’94, right before the election. There were different proposals coming out. The House had trouble passing it through its committees. [George] Mitchell had an attempt to save it in August. Chafee’s proposals didn’t really go very far. It’s not clear to outsiders why it both went on for as long as it did and why it didn’t work.

Simpson

We even had a bipartisan Senate group: [John] Breaux, [William S.] Cohen, [Nancy] Kassebaum, and others and I would drop by with the other Democrats and Republicans. We met every week. We talked about single payers and double payers and all participants and all

stake holders.

I’ll tell you frankly, nobody understands what the hell to do with it, because they don’t understand it. You can talk about it all day long and we would try to learn. Good teachers were [Alain] Enthoven and [Paul Ellwood]—we would have seminars with them. They would describe how well it worked in theweed and pest control district

and how it could work in the federal government. Somebody then would always ask those questions that are so persistent and arcane that you really can’t answer them. And the fog closes in.Then someone would say,

What do we do to craft that?

The only reason there isn’t revolt in the health care world is because, of the 43 million who are uninsured, they’re not uncared for. As long as they can go to an emergency room and cost us double what it would cost if we had a health care plan, they’re not up in arms, and nobody else is either. So here you now have Obama and [Hillary] Clinton and [John] McCain all talking about health care, but it’s like reading an Egyptian newspaper; nobody really knows what it is, except you have to say,You’re going to get taken care of. You can’t afford it; we’re going to take care of you.

It will cost trillions.But Hillary, you know, she suffered with that original initiative, because people didn’t like that intrusion. Then of course, on our side, I’ll never forget, Arlen Specter had a chart. It was an amazing chart, as big as this window. It said,

Here’s what Hillary’s plan does and here’s how many things would go on it to make it work: layer on layer on layer.

Whether it was right or not, it was a classic piece of an extraordinary overlay of bureaucracy.Martin

A chart that was probably 8 feet by 8 feet?

Simpson

Oh yes, and it had hundreds of little things, assistant this or that and what about the guy with big toe disease and all the rest of it. It was amazing.

Martin

One of the things that people don’t understand, or are unclear about, is that one could attack a policy for being complicated for political reasons, or one could attack a policy for being complicated for legislative reasons, that it would be bad policy. Do you have a sense at this time whether folks in the Senate were attacking this policy genuinely on policy grounds or was it

Let’s hit Clinton

?Simpson

I think it was policy grounds, although it was felt that she shouldn’t be doing this. She was the First Lady of America. She would have sessions with the Senators. She would say,

I’m coming up to talk about my health care plan.

That was rather unheard of. We would sit and ask her questions and, boy, she knew the answers. She had staff with her. I think there was an element that felt this was not the role of the First Lady, and furthermore, she seemed rather stubborn, authoritative, and dogmatic in the presentation of it.One day when I was visiting with her I said,

I have an idea.

Carol Moseley Braun was standing there also, the two of them. Carol was a great ally of Hillary’s. I said,I think that anyone who goes to a doctor, for a doctor’s visit, should pay $5 in cash. Let them realize that they’re in the greatest country on earth and that for five bucks, which is less than a movie ticket or a pack of cigarettes, they can get the amazing care that they’re going to get.

They both said—and it surprised me—That’s quite an idea.

I said,It would raise X billion over the years and it would make everybody know that you’re in a country where, for five bucks you get the best.

Realize now there are thousands of people who go to a doctor just to have the doctor touch them and hold their hand, because nobody else does; they have no one; no one gives a shit about them. They go to the doctor and the doctor says,

Now my dear,

to an 80-year-old lady,I think if you’ll do this . . .

Well, thank you so,

she says. That’s like a life injection. That’s maybe maudlin or emotional, but it’s true.The three of us agreed it was a good idea—but once we floated that, the show horse neighed and said,

You mean to tell me that the poorest people in America would have to put up five bucks?

I said,They buy cigarettes and go to movies for more than that.

The response was,Oh Jesus, you barbaric bastard!

Finally Carol Moseley Braun said,Alan, I can’t play with that one anymore.

I said,Well, you’re from a tough constituency. I don’t blame you.

But anyway, it’s ghastly.Martin

How receptive were they to the proposals that were coming from Chafee and what is called the Main Street group?

Simpson

I think they listened; everybody listened, but when you lose people from the Senate like John Heinz [III] and Bob Packwood or Jacob Javits, who could explain complex things, you’re doomed. Javits could get up without a note and describe necessary changes in ERISA [Employee Retirement Income Security Act] and the rest of us would just sit there and say,

Hey, good idea, Jack,

because he really knew the issue. Heinz and Packwood, who were both gone from us then, were the only ones who had previously spoken with clarity on what to do. You had other people who knew the terms, or you knew they knew the terms, but you didn’t know the outcome of the terms in the many plans.Martin

There were people there who had been working on health care for a long time, but they didn’t have the same credibility that Javits would have had on technical things?

Simpson

I don’t even remember. No one ever had the acumen of Javits, no one. But Heinz and Packwood knew the issue—other people knew the issue, and their staffs knew the issue, but it was always

maybe this would work.

It takes six to eight years to do a major piece of legislation, because then everybody in America has had their say, but in this situation—I don’t know. I wasn’t involved. I went to the meetings because I was assistant leader, but it wasn’t for any health care expertise I had. My expertise, whatever it was, was in immigration, nuclear high-level waste, veterans’ issues, Social Security, and legislating. I could play in there all day with half a brain, without staff telling me everything. But health care? Don’t ask me. I’m not good in that game; I was lost in it.Martin

Let me push on this a little bit. Almost every issue that the Senate is going to face is going to be technical enough that only a certain portion are going to understand it completely.

Simpson

That’s right.

Martin

I’m trying to get a sense—Was it not just that Javits knew what he was talking about, but that people trusted him?

Simpson

That’s right.

Martin

Do we not have enough of those folks?

Simpson

There’s very little trust now. Trust is a fleeting thing in the U.S. Congress. They’re afraid someone is going to go have a press conference after they’ve talked privately to you. I can’t tell you how many times we’ve sat in a closed meeting to discuss how to do this or that and have said,

Can you please hold any comment on this, so that we can work it through the rest of the troops for their views?

And that night on the evening news would be one of the sons of bitches who was in the room who got some nice coverage out of that confidential matter. His or her staff would be very thrilled that they were on national television that night blabbing a sensitive part that if you could have worked it just a little longer through the system you could have gotten there, but you couldn’t because some of the emotion, fear, guilt, or racism would slap you in the face. I can’t tell you how many times Dole and I would say, figuratively,Now, will you just shut up? We’re not trying to screw America; we’re trying to work with a sensitive issue and that if you come out with it, without a full knowledge of what we’re working around, it isn’t going to work.

That’s what happens with that stuff.Health care—Clinton and Obama, what are they talking about? Can you tell me?

Martin

No.

Simpson

You can’t. And the American people listen—he says that she has everybody paying and she says no, only so many people. Nobody is paying any attention, except that the people want coverage. That’s not a partisan statement. I’m just watching them talk about that singular issue of the campaign, and I don’t know anything more than when it started, except they each have a catch phrase, each of them, that the other one doesn’t agree with. McCain also has his phrase.

Martin

Let’s move past health care. We come to the ’94 election. The Republicans took the House. You picked up a seat or two in the Senate.

Simpson

Right.

Martin

You became the majority in both. Then you lost the whip position to Trent Lott. Can you talk a little bit about the politics that led up to that conflict between you and Lott for the whip position?

Simpson

I was just a big lug fast asleep. [laughing] There’s no mystery to it at all. I had already said to all my colleagues,

Look, I don’t want to be the leader.

I did it once for 15 weeks, when Bob Dole ran for President. I was the leader—Martin

Back in ’88.

Simpson

Yes. I said then,

All I want is for you guys to stick together.

Well, they did. It drove old Robert Byrd crazy sometimes. We had one issue where he pulled the trigger on us for eight different cloture votes. They failed each time, and then called for a live quorum. The Sergeant-at-Arms went into Lowell Weicker’s office and said,Senator Weicker, the majority leader has asked for your personal physical attendance.

Weicker was 6′ 7″, and weighed 240, and he said laconically,Get your ass out of here.

The Sergeant said,Yes, sir.

That was the end of that. They carried Packwood in with a broken leg, remember? The press loved the picture of him.Martin

No.

Simpson

This is how it used to work as regards comity. This is not romance. I was the temporary leader and I knew I could never match Byrd with regard to procedural activity, because he was a wizard, but I knew that if I could stall him one more time, he would drop the issue. I think it was something about campaign reform.

Martin

Could have been.

Simpson

I went to Kennedy. I said,

Okay, Ted, I know you have a parliamentarian on your staff. You pay him out of your own pocket. I want you to give me that son of a bitch. [

laughing

] Would you loan him to me so I can get out of this box?

He said yes. This parliamentarianstaffer

came over, and said,Yes, sir, Senator, you could do this. You can quote from section 34D and predecessor so-and-so and all the research,

and so on. He just babbled, but I went to the floor and said,Mr. President, under rule 34D and the precedent of the language found in the 1913 volume of the U.S. Senate—

Well, the guys just stared. The parliamentarian—the leader picks his own parliamentarian, you really do, although they’re supposed to be unbiased, and they are, and very good. I said,Do I have a correct interpretation of that?

And he said,Yes, it’s true and the Senator is correct.

Byrd looked up like, Where did this guy come from?Then Robert Byrd came to me. He said,

Alan, let’s just end this. But I want you to give me another day or two, perhaps going all night. I don’t want to be embarrassed.

I said,I wouldn’t embarrass you in any way.

He withdrew his fangs from my leg and he did it with grace, without losing face. Anyway, I never wanted to be leader.Somebody came up to me one day a couple of years before the last whip race and said,

Do you know that Lott is after your job?

I said,Really? That’s a surprise to me,

so I sat down with old Lott one day after a vote. I said,Are you interested in this whip job?

Oh,

he said,no, for heaven’s sake, you’re the best whip we’ve ever had.

I was sitting there big, dumb, and happy. I said,I just wanted to check on it, I had heard that.

What he was waiting for was that next election. I was out in California, giving a talk or something. My chief of staff called and said,

Trent Lott is in this race.

I said,Good grief.

I got on the phone, starting to call everybody and they were saying,I’ll get back to you.

Olympia Snowe told me that when she was in the House with him, he said,You know I’m moving over to the Senate, and if I ever run for anything over there, will you help me?

She said yes. He did that with every person of his party who either came when he did or came afterward, so he had all those new guys. That was enough to tip the balance. It worked.The minute the vote where he was the victor was announced, I grabbed him by the arm and said,

You and I are going out to talk to the media right now. I’m not going to wait a day, we’re not going to cook crap.

I went out and I said,Here is the new assistant leader of our party.

I then went to the television studio with him and that was it. Already the table setting at lunch was for me and Ann to be sitting there in front as assistant leader. I said to the gathering,I’ll be sitting at the back, this is where you [Trent Lott] and Trish [Patricia Lott] will be now!

That’s the kind of transition to have—you don’t want to cry. You want to get the lump out of your throat as quickly as you can because—really I was stunned; I thought I had three votes to spare. That’s the way it works.That was how he began his trajectory. I saw him last night. He’s a good friend. Every time I’d come to Washington after that, I’d go in to say hello to him. Then it was devastating to him when he got shot up about the Thurmond comment.

Martin

When I was preparing and reading through old CQs [Congressional Quarterly] and National Journals, I didn’t understand why he challenged you, in part because it seemed as though the main job as whip was to get people together for votes and you had done that, especially in the last couple of years. It didn’t seem like there was a lot of justification to challenge the sitting whip.

Simpson

There really was, in his mind. I was not conservative enough. My main defect was that I was pro-choice.

Martin

Wouldn’t that have been Dole’s job, to set more of the tone of the legislation being brought up?

Simpson

Yes, but it didn’t matter about Dole; it was me and my philosophy. I was not conservative enough for the new era. I was older, getting to be 65; pro-choice;

liberal.

Simpson is a liberal. Maybe we should replace him with someone more conservative and younger. It was a case of the same things that turn voters on in any society. It was very effective.Martin

I didn’t realize that Olympia Snowe was one of the folks who voted for him. She’s not conservative.

Simpson

No, but she is a woman of great authenticity and honor. She told me,

I never knew it would be you, but I promised him that if he ever ran for a leadership position in the Senate, I would support him, and he said, ‘Here’s the time.’

Martin

That vote was by one vote in the end, 23-24.

Simpson

Something like that.

Martin

How does that affect a caucus when a vote is that clearly split?

Simpson

It doesn’t affect it at all if the loser just grabs hold of the winner, goes out, pays homage, and says,

I’m going to support this person to the best of my ability.

That’s what I said and that’s what I did.Martin

Your action made it all fine. But had you not done that, would it have signaled a rift?

Simpson

It might have been a little different if I’d gone off and pouted and said,

Who are the three bastards who screwed me? I’m going to find their names, so I can have a good talk with them!

Martin

It sounds, to some degree, like the story of when Kennedy lost in the late ’60s; he was whip at that time and lost to Byrd.

Simpson

He lost to Byrd by one vote. Chris Dodd, the day I was beaten, was also beaten by one vote for assistant leader of the Democrats. We’d served together in the Senate; we both now were out of the leadership. We said,

God, our fathers—who both served together in the Senate—would be proud of us today; we both got our asses shot out of the saddle by one vote.

Martin

How did the strategy of confronting Clinton change after 1994? You had a new leader—Dole was still the majority leader, but you had a new whip. I don’t remember who the number three was at that point. Lott was supposed to signify, to some degree, more contentious politics.

Simpson

Yes, but then after I was beaten, I began to sort it out really fast that I’d had the best of all worlds. George [H. W.] Bush had been President for four years and we were very close and were throwing snowballs off the White House roof one night. Those things you’d never see again; dinners of just the four of us, Barbara and George, or Dick and Lynne Cheney, so you think, Six years!? I can’t do six more years of this. Right after that, I began to think; that sowed the seeds of I’ll get out. I’ll never have another President that I know and care for so much; it doesn’t matter what party.

I really don’t know much about what went on after that, because I was out of the whip’s office, now just one of the loyal soldiers, like a

short-timer

in the Army, as we used to call it. As to what they were doing to Clinton’s policies and so on, I remember few votes. If you brought something up, I could tell you, but I was not in the inner circle of what to do. I’m sure Trent was. He was ready to go; he was loaded for bear.Martin

Can you talk a little bit about Dole’s relationship with Newt Gingrich, on policy? It doesn’t need to be personal.

Simpson

I can only tell you mine. Here we were, both assistant Republican leaders, so I said,

Let’s meet together.

He liked that idea. He might have suggested it.Let’s get together once a week.

I said,Great, I’ll come to your office first.

I went over there. There were three books on the table. He said,I read those this weekend. I’d like for you to take a look at them and then we can talk about some of the themes, some of the aspects of that that we might adopt for ourselves.

I said,You read all three of those?

He said,Yes, I did.

I said,

I haven’t gotten past page 142 of

Lonesome Dove

; what am I supposed to do with these?

He stared at me. I said,I’ll give it a little try, though.

I got into it. It was just arcane bullshit to me; it meant nothing. The next week he came over to my office. He said,I have another couple of books.

I said,What am I supposed to do with these, Newt?

He said,Please read them and then we’ll talk about them.

I said,

Why talk about books? Let’s talk about what the hell is going on in here. You’re the most creative, brilliant guy.

I’ll tell you he is, still is. Finally, after several of those visits, he could see that he was playing with Joe Palooka and he said,Then what did you do this weekend, if you didn’t read the books?

I said,I went to see the new [James McNeill] Whistler collection at the Freer Gallery, and we went to see the new collection at the National Portrait Gallery, spent a lovely afternoon at the National Museum of American Art, went over to the Library of Congress, looked at some of the ancient books, went to the Folger Shakespeare library, down in the vault. I know a lot of Shakespeare, love Shakespeare.

We were like two trains passing in the night on different tracks, so we didn’t meet anymore.Yet he also worked with the Library of Congress and helped set up that new high-tech system over there. Amazing what he and [James] Billington had cooking over there. Brilliant, brilliant man, but his was not my style of leadership. He was a leader. He pushed Clinton to the wall. But I don’t think Dole ever spent much time with him.

Martin

The policy that they pushed wasn’t picked up in the Senate.

Simpson

What?

Martin

The Contract with America wasn’t picked up by the Senate.

Simpson

They were always frustrated, just as they are now. Here they controlled both bodies and the House was usually pissed off at the Senate. That’s the way it works.

Martin

They’re destined to always be pissed off at the Senate.

Simpson

In fact, you could copy it all right now. The House Republicans would say then,

That damned Dole

.

The Democrats now in the House are now saying,That damned Reid.

Martin

It seems almost structural, that those fights are going to be endless. When you think back about this period, what do you think of as the defining moments of those first two years of Clinton’s administration, the big things that we should pay attention to?

Simpson

The defining moments of his first two years?

Martin

Yes, ’93, ’94, before Gingrich took over the House.

Simpson

Getting to know him and seeing his style. Don’t forget what he went through. Not the issue of his wife—the toughest issue. I don’t know. To me it was seen during our going to the White House. I remember one time particularly. Remember Somalia? That was a terrible thing; they dragged our dead soldier down the street.

Bill got us all down there and we were having a bipartisan meeting, probably twelve of us from the House and Senate, Republicans, Democrats. He got going on Somalia and what he was going to tell the American public. He said,

Here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to share it with you, just bounce it off you.

So he did; it took him about 25 minutes to do that, which was not uncharacteristic. [laughing] He finished up. He went around the room and said,Simpson, you look like you didn’t quite believe all that.

I said,

I’ll tell you, Mr. President, it was a wonderful presentation, but if the guy on the barstool in Buffalo, Wyoming, can’t understand it in about seven to ten minutes, it isn’t going to go anywhere and nobody is going to understand it.

He said with humor,Thanks, I’m glad I invited you over here today. Thanks, Al.

There was some laughter and stuff. About four days later, he gave a hell of a talk on television about Somalia in about seven to ten minutes. Then he saw me a week or two later and said,You think the guy on the barstool in Buffalo picked that up?

I said,You aren’t kidding.

That’s the way he was. He listened to people.I’m in his book. He called me in Cody.

Al, this is Bill Clinton.

This was, what, three years ago? Yes. He said,I have a quote in here, and I want to be sure this is what you said.

It was something aboutright-wing conservatives.

I said,No, I used the words ‘right-wing extremists.’ Get that right. It was ‘right-wing extremists’ who were going to cause you pain, and the media, because you were wounded.

Anyway, it’s in the book.He went on talking,

Now, do you know why Hillary carried upstate New York?

He had some theories about women tennis players whose husbands were staying in New York while they were running off with the tennis pro. There was much more. You could have recorded it; it was sensible and it was a riot. We were joking and laughing. Then Ann came in. The speakerphone was on. I said,It’s Bill Clinton.

Ann said,Hi, Bill.

He said,Ann, how are you?

He’s a charmer.Forget all the other stuff, and I do forget it, that’s why I enjoy these other people of the

other faith.

I guess it’s because of my own life. Every turkey in my cage was released. I was on federal probation for shooting mailboxes. I was a goddamned monster. I slugged a cop and got thrown in jail when I was at the University of Wyoming, was often drunk for a couple of years—at least other people thought I was—so any of these flaws of the human condition don’t affect my relationships with others.I grew up with irrigators. You know what an irrigator is? They’re out in the field with boots on and a shovel, turning the water in the ditches. We never knew who they were.

Where are you from?

The East.

From where?

East coast.

What did you do before you got to irrigating?

Worked.

They may have killed somebody and were on the lam, yet they taught me how to play cribbage, quote Shakespeare—Enough of that. That’s personal aggrandizement.But he really is one of the most popular former Presidents—and Bush. He and Bush hit it off together on their tsunami trip. I talked to George before they left. I said,

Get to know him, I think you’re going to like him.

George said,I never disliked him.

I saw Bill then later going somewhere, not sure where—and I said,I hope you’ll enjoy your trip with Bush—he’s a great guy.

When they came back, I didn’t see Clinton for a long time, but I saw Bush. I said,How was it?

He said,Well, he’s an amazing man, was very deferential to me. He treated me like a father figure—and I guess I am! There was only one big bed on the jet and he’d say, ‘You take eight hours and sleep.’ I said, ‘We’ll split it; you take four.’ ‘No, no, no.’

He said,I enjoyed him very much. He’s thoughtful and kind. Only one thing, Al. He talks a lot.

[laughing] I said,Oh, we all know that.

But Bill’s conversation with me that day in Cody was thirty or forty minutes. He just reviewed so many things in a kind of stream of consciousness.Anyway, the thing that really is interesting is that this current campaign has hurt him, which is unfortunate, because he really was and is one of the most popular men in America, but now this little thing in South Carolina about Jesse Jackson, that little shot hurt. He was pissed; you could tell he was pissed, when you know him like I do—saying about Obama,

It’s a fairy tale, this guy is telling a fairy tale.

That hurt him a bit, but he’ll work through all that.Martin

People will forget about that, I think.

Simpson

I don’t know if I answered your question!

Martin

Let me ask you one last question and then we’ll call it a day. Did you get a sense that he came into the Presidency in ’93 and that he learned a lot about the Senate, or do you think he already understood the Senate when he got there?

Simpson

No, no, he never understood the Senate when he got there, because he’d never been a legislator. When you come into the Senate as a Governor or professor or teacher, you’re in deep crap. I’ve watched Governors come there. When they come, they’re used to getting things done, seeing people do what they ask them to do. You’re the Governor; a state trooper is driving you around to the meetings, the speeches, to concerts and to your office.

Here you’re driving your own car or else paying somebody out of your own pocket to do it. I think all Governors that I watched come here were stunned.

By God, nobody does anything for you!

Dan Evans, he didn’t like it. He just took one term. The only one I think who handled it pretty well was Dale Bumpers, but he was a man of the red earth anyway, a great friend. But they can’t see the clear results of their actions. If they’ve never been a legislator, they look upon a legislative body as a bunch of goddamn, know-nothing clods. My dad was also a Governor and he’d say,My God, I hope the legislature leaves town soon because of the pettiness that goes on during the session,

even among those in his own party.So Bill had no idea of the arcane workings of the U.S. Senate, except he learned fast. He learned to use the Senators. He learned to use the savvy and experience of Pryor and Bumpers and Lloyd Bentsen and other people of his party—and learned to know and involve others of us who were not of his party. I don’t know who else, of the Republicans, but he worked with Chafee and Durenberger and many of us. You’d know better, you’re doing the history!

Martin

We can call it a day.

Simpson

No, this is something more about Bill Clinton. I was out of the Senate and teaching at Harvard. A vacancy opened up for the Ambassador to the Vatican. Mike Sullivan was the former Democrat Governor of Wyoming—he and Clinton were Governors together; and Hillary and Jane Sullivan are great friends, a nice friendship. When Clinton was first running, he was in tough straits in New Hampshire—hanging by his left nut—and he called Mike and said,

I need your help. I need a friend like you to come to New Hampshire.

Mike said,I’ll do it.

Clinton was not popular in Wyoming—I can tell you that! Mike, in the dead of the night, went to New Hampshire, met Clinton, and campaigned with him. Maybe Jane went, I don’t know. These are dear friends of ours, Jane and Mike.Then Mike later ran for the U.S. Senate against Craig Thomas. Mike at that time had a 66 percent approval rating in Wyoming as Governor. That’s big. The opposition pulled up pictures of Mike Sullivan and Bill Clinton campaigning. Big pictures. And the ads read:

Is this the guy you want to go back to Washington, just to see his old pal Bill Clinton?