Transcript

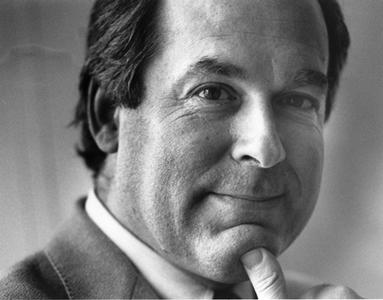

Riley

This is the Eli Segal interview as part of the Clinton Presidential History Project. For the record, the interview is taking place on the 16th floor of the Brigham and Women's Hospital. Thank you very much for letting us come and be with you. We can talk about ground rules some other time. I think the thing to do is to go ahead and start on the interview. I thought I would begin by asking you if you remember the occasion when you first met Bill Clinton.

Segal

Clear as day. It was September, 1969, in Martha's Vineyard at the home of a very good friend of mine named John O'Sullivan. It was a meeting of about 15 of us who had worked together in the Gene McCarthy campaign the year before. We all thought that we were the king of the walk, that each of the 15 of us were only going to discuss which of the 15 of us was going to be President of the United States. We had been real hotshots in '68 and were upset that despite our best efforts the Vietnam War had not been affected at all by our brilliance in the Gene McCarthy for President campaign. We were going to get together and retreat, and figure out what we could do, if anything, to affect the outcome. Every one of us had been in the McCarthy campaign. But one of us, one of our good friends, had spent the year from '68 to '69 in England, specifically in Oxford. His name was Rick Stearns and he had had a roommate who had not been in the McCarthy campaign. He asked if he could bring his roommate to the retreat and we grudgingly said yes. That roommate was Bill Clinton.

He came with his roommate and his roommate completely captivated the group so that within a few hours—you would think that someone would be a little standoffish, a little skittish about meeting 15 new people, all men. It wasn't the days of the feminist revolution just yet. He was invited and he was great. I developed a particularly close relationship with Bill—then "Bill" to me, and "Bill" for many years thereafter. I don't exactly remember why. I remember we spent some of the time water-skiing or attempting to water-ski in the Tisbury Great Pond in Martha's Vineyard. I don't remember us being very good but I do remember us being deeply engaged in one discussion or another that young people think are very important that probably aren't all that important but seemed to really bring us together in '69, which was 37 years ago. We remained close from that point on.

The first thing that I can remember thereafter is in 1970, one of our group who was not at that retreat, named Joe Duffey, announced his candidacy for the Senate in Connecticut and we all plowed into the Duffey campaign. Bill Clinton, while at Yale Law School now, was running one Congressional District. I was, I think, called the general counsel, and had other responsibilities because I was in Washington. No, I couldn't have been the general counsel because I was working for George McGovern by that point, not in the Presidential campaign but in something else called the McGovern Party Reform Commission—which if you don't know about I'll double back on with you at another stage. So I had to keep a little lower profile since I was working for a United States Senator at the time, but I believe I was organizing some of the towns. We had a town committee system in northwestern Connecticut, it happened to be the town of Ralph Nader. And Clinton and I continued to be very good friends all during the '69-'70 campaign.

Riley

Clinton was an Arkansan working in Connecticut. Did that create any dilemmas?

Segal

No, despite the accent, despite—I think he was with a beard at that point, I'm pretty sure he was—because of his charm and his skill. Let's not understate his skill, his persuasive skill. So during the '69-'70 campaign we became even closer. In '72, the next thing I jumped to, I became the deputy campaign manager to George McGovern in his Presidential campaign. The other deputy campaign manager was Rick Stearns and the third was Harold Himmelman. Among the three of us—I don't remember exactly how it was done, I'm pretty sure I was in charge of choosing the state campaign managers and chose Bill to be the campaign manager for us in the state of Texas. The campaign manager with Bill in Texas was Taylor Branch, the now-famous author. My involvement with Bill during the '72 campaign was really limited since geographically his role came under Rick Stearns, who ran the midwestern part of the United States, while I ran the northwestern part of the campaign. Himmelman ran the eastern. I don't remember how we divided it up but since all three of us lost those states, none of us went around bragging about the outcome.

So from '72 we were friendly. From '72 until he ran for President, our relationship was generally I'd write a check whenever he ran for an office, I would certainly advise him to the extent that he would reach out, and because I ran a company I tried hard and I think I succeeded in bringing some business to the state of Arkansas. There was a frame manufacturing company that my company bought some time in that period of '72 to '91. It was a valuable purchase—I'm pretty sure we ultimately bought it, not 100 percent sure but I think we did.

In that period also, while I wasn't directly involved in many campaigns, I managed to lose in a few despite having lots of day-to-day activity. In that time I lost in the Birch Bayh campaign, the Mo [Morris] Udall campaign, the Teddy Kennedy campaign in 1980, the Gary Hart campaign, where I had a very active role. I was the chief of staff and played a very big day-to-day role towards the end of the campaign. When the then-campaign manager ran into quite serious charges, serious management problems, Gary Hart asked me to come up and run that campaign. Then I was the campaign finance chair in Gary's 1988 campaign, which started in 1987. That was the infamous Donna Rice campaign. So I was actively involved in 1987 and '88.

Having run and lost in all those campaigns, in 1991—[interruption by nurse]

Riley

I wanted to ask a question about this period. You had worked for Hart in '87 and '88. Bill Clinton evidently came very close to running himself in 1988 and called a lot of his close friends to Little Rock for what many people perceived to be an announcement. I wonder if you have any recollections of that? Were you called to Little Rock for that meeting?

Segal

Yes, I was, and the timing is important. The Clinton meeting in Arkansas was after Gary Hart had dropped out. He wanted to run that campaign much along the same kind of new ideas, new vision, new politics themes because he so admired Gary. I felt I really needed a rest. I was encouraged by every one of the people—from Sandy [Samuel Berger], my very close friend, to Carl Wagner, to Mickey Kantor, to John Holum, to other names you've heard—to participate, and I was just too tired. We also knew enough about Bill's own problems, if you will, and I just couldn't, after Gary Hart, go through another one. I was the happiest man alive when he chose not to run, happy for him but happy that I had made the decision not to get involved.

It was a time also that Phyllis was very persuasive that this was not the time for my eighth losing Presidential campaign, it was the time for some family activity. Instead of going to Little Rock we went to London, a much better alternative, at least for the Segals. Instead of going to Little Rock and instead of going to work for Mike Dukakis, which I had no interest in doing at all, we moved to London. We had a fabulous year in 1988 and '89.

Riley

Doing business?

Segal

No, no. It was a sabbatical, believe it or not. My mom used to say that I did two things. I did politics and I did business, and if I had been as good in business as I was in politics, I would make the depression of the '30s look like small potatoes. But in business I was pretty good and I had some pretty good successes in a couple of companies. The sabbatical was a purely, 100 percent freebie that we paid for ourselves, and we spent a lot of money. We always said that when we left England, Maggie Thatcher was going to get on the ground at the airport and say, "No, the Segals can't go! They're single-handedly propping up the government here in London." We spent, again, a lot of money, had a great year.

Mora [Segal], our daughter, was with us, which was terrific. Fourteen-year-old girls usually don't want to be away from their buddies but Mora was prepared to do it. She went to school. I taught a course. In fact, it was a course on the history of American politics or American Presidential elections. I remember saying at the first lecture, "You are the dumbest people in the world to be in this class. You're talking to the only guy who has lost seven Presidential campaigns in a row. But maybe you'll be able to make it through it and together we'll learn something interesting."

Riley

Where did you teach this?

Segal

At the university, Imperial College. The year was great. Phyllis took some woodwork and carpentry courses, and a course on the history of art. I took some courses on the history of the city of London and I took another great course, 19th century England. We broke the world's record for going to the theater that year. We went everywhere, it was a great year.

Riley

You got your batteries recharged.

Segal

Correct, it was the purpose of the year. Plus Bill Clinton didn't run. Fast-forward to 1991, I had only one candidate in 1991. He wasn't the most "liberal" candidate, which I had always identified myself as, but he was a very close friend who I thought had a pretty good chance of winning.

Riley

Did people in the community of folks that you tended to move in, who I assume were primarily liberals, were they skeptical of Clinton? Did you have a big sales job with that community?

Segal

I think I made it clear right off the bat that under no circumstances would I support anyone other than Clinton. I got a rush from Bob Kerrey. And then Jerry Brown was thinking of running, Tom Harkin was thinking of running. For me it was friendship but also a belief that Clinton had thought through what it meant to be President, and to go down again just to say I was a good liberal was silly. I loved his DLC [Democratic Leadership Council] platform. I had become deeply, deeply committed to changes in the welfare system. I didn't really understand his idea of national service but it sounded like a very nice idea. That's all I knew about it. I believed that as long as the Democrats were mired in the old protectionism, they couldn't possibly win. Unless they had someone who could stand up for free trade and who could stand up for a change in the welfare system, they would lose again.

Riley

In 1991, then-President [George H. W.] Bush's poll numbers were extraordinary. Was there much concern at that point about Democrats not taking on or having your good friend take on a President who—

Segal

I never looked at it that way. George McGovern must have been losing to Ed Muskie, Arnie's candidate. Was Muskie your candidate?

Miller: Are you kidding me!? [laughter] Tony Podesta worked for Muskie. Jim Johnson went to Muskie.

Segal

Alan Baron.

Miller

Alan Baron went to Muskie.

Segal

[John] Lindsay? Who was your candidate?

Miller

I turned Lindsay down because I didn't want to work against my cousin, who was for McGovern. I went to New York. They wanted me to go to Florida for Lindsay.

Segal

We still have these fights. [laughter]

Riley

I can tell.

Segal

No, it never affected me. I chose McCarthy. I chose McGovern. That was because to me politics was not about how you get a job in the White House. And I did Clinton—well, it's a little complicated. Early on I did not do Clinton, not because I didn't love him and want him to be the President, but because I had just bought a company in the middle of '90 and needed to consolidate the company. It was a magazine company called Games. I needed all of my time in '90 and '91. I was approached ten different clever ways, by some combination of Bill Clinton, Sandy, Harold Ickes, maybe Mark Gearan—all names you will know quite well—to run the campaign, and I had the wherewithal to say, "Look, I'll help but I just can't do it, not because he's not going to win. I think he's pretty good. He's got a lot better shot than George McGovern—" whom I didn't support, didn't take on an early opportunity to run his campaign because I just couldn't bear losing again— "but because I'm just not ready."

I volunteered to help. The facts are a little bit murky but I think I've—in anticipation of today, I've worked out what I believe was the case. In October of '91, when he announced his candidacy with a lot of hoopla at the state capitol in Arkansas, it drove Bill Clinton crazy that he had announced his campaign and didn't have a campaign manager. One deal or another came along to me and I finally agreed that what I would do would be to go not to Little Rock but to Washington, and interview 50, 100, 150, whatever number of people it made sense to interview in order to put together a crackerjack team. That was something that appealed to everybody because while [Stanley] Greenberg and [Frank] Greer and [Al] From were fighting for what their own roles were going to be in it—I don't want to say that too cynically because I don't mean it cynically. One of them was a great pollster who wanted to make sure he would do the polling; one was a great advertising guy and he wanted to do the advertising; one was a great strategist—there was no [James] Carville and [Paul] Begala around at that point—From wanted to do the strategy. And they all should. But there was no glue person, kind of what my role was historically in this thing, to bring the pieces together.

So I went to Washington, interestingly to the law offices of Susan Thomases, to the basement of Wilkie Farr & Gallagher, her law firm. An interesting and a small footnote, it was the time of the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings and it was a very tough time because it was clear to me that every African-American female in that firm was going to support Clarence Thomas, except when the partners came along, then they would suddenly be supportive of Anita Hill. So I understood the racial divide then, it was stunning, but that's neither here nor there.

In rapid fire I brought in—I hired one person who happened to be my son's college roommate to assist me with resumes, telephone calls, meetings—and over a very short period of time, I'd define it as a week or two, I hired everyone from David Wilhelm to Dee Dee Myers to, more or less, Rahm Emanuel to Richard Mintz, who became the campaign manager for Hillary Clinton, to Stephanie Solien, who became the political director, and I think one or two more. Clinton said to [George] Stephanopoulos, "You're hired. However, until you meet with Eli Segal, you're not hired." Clear instruction to me. Clear instruction to George. I met George, whom I had never met before, and I could tell this was a real talent. I spent a maximum of a half-hour with him and said, "Okay, you've got the job."

Riley

There was no question at that point with George about his ultimate loyalties to people in the party?

Segal

To Kerrey and to [Richard] Gephardt?

Riley

Right.

Segal

No. I felt, staring George in the face, that he understood this was—that Gephardt must have made the judgment that Gephardt wasn't going to run, that Kerrey couldn't win, that his old relationship with Dukakis was just that, an old, former relationship, and I felt that he understood Clinton the way I did, as offering something new. He said this was his man and I didn't question his loyalty for a second. How I managed the Wilhelm thing—do you like this anecdotal stuff?

Riley

Absolutely.

Segal

The reason I'm going to speed through this is that from a historical perspective the AmeriCorps stuff and the Welfare to Work stuff are, to everybody in the world except me, the more important stuff and I'm going to go with everybody else here. First I called the last boss of Wilhelm, who was Dick Daley. I said, "I want you to talk to me about this guy." Then I called his brother, Bill Daley. Then I called the head of advertising, who had done all the advertising for the Daley campaign, a guy named David Axelrod. I got sterling reviews from all. I may have called Joe Biden, whose campaign—I don't think Wilhelm ran his whole campaign but he had a large role in the campaign—and got another great review. Checking different things out, his personality, how he would deal with stress, what kind of leadership skills he had, et cetera. All top-notch reviews.

Based on that, I called Bill Clinton, who was flying in an airplane to Capitol Hill to a hotel on New Jersey Avenue. I said, "Bill, I've got your campaign manager." He said, "Who?" "I'm not going to tell you. I'm not going to do it that way so you can brood about it and say, 'Maybe yes, maybe no,' I'm bringing him into the room. You're going to shake his hand and he's going to be your man." I don't remember the exact dialogue, I wish I could, but he said, "Eli, if he's good enough for you, it sounds pretty good to me." He hangs up the phone. I learned from Lindsey that Bill then says to Lindsey—he was "Bill" for me until the moment he was elected President, then he slowly became "Mr. President"—so Bill says to Lindsey, "Eli says he's got the campaign manager." And Lindsey says, "Congratulations." [laughter]

You'll want to check on this but I think I've got it right. I walked into Clinton's room, put Wilhelm and Lindsey into a separate room, and I said, "The guy through that door is going to win you the Presidency." Clinton was very good about this. To his great credit he didn't go back and forth, and, "Well, what about—" He said, "Let's go." And I had said to Wilhelm, "If this guy offers you the job, you're going to take it, aren't you? I didn't do all of this and pay with my own credit card to bring you here for you to say no. Take the job." The rest is history there. I don't remember what happened after that other than he was very happy. Both of them were very happy. We announced at a press conference and Wilhelm was aboard.

Well, it wasn't very long after that when Gennifer Flowers hit. First of all, Clinton's polls at that point were very good. They had gone up, they had gone down, gone up and down, but this was a pretty good time in the polling. The Wilhelm announcement didn't hurt, but it's a functionary position and it didn't stay up there for long. Gennifer Flowers hit, all hell breaks loose. Clinton calls several people and asks for help.

Riley

You're in Boston at the time.

Segal

I'm now back in Boston. I'm back running my companies. I thought I had finished my work, which was to put the team together. I wasn't running the team but I put the team together. Clinton reached out to Carville, Begala, and Mickey Kantor to play not insignificant roles in New Hampshire, and I think Mark Gearan, although he had a less important role, as I remember it, than the first three. And he reached out to me to go to Little Rock and assess how all this pressure was affecting the team, how they were doing, and what we should do about it.

Riley

So rather than calling you to New Hampshire to deal with the pressure in the bubble there, your role was—

Segal

Correct. To go to Little Rock. I went and it was clear that there were problems. Wilhelm was good but it was clear that what David does best, and he'd be the first to admit it, is politics. He knows ward politics, union politics. He knows, long before you make a move, what you're going to do. He's a master at it. But he's not good at organizational growth and I may have missed it a little bit but I think in politics below the national level it's harder to see. We may have missed it a little bit. He may have, in the interest of making sure all the work he had done— making sure that Congressman X and Congressman Y were there even though they didn't like Clinton's emerging position on issue Z—all of that is where he put his time. And he had loyalty from the staff but there was no sense of coalescence and no real movement in the staff to deal with this kind of unexpected pressure.

I went back to Clinton and said that I believed what I have just told you was the case, but I also said, "I believe David Wilhelm would view it as an extraordinary relief if somebody came down and really gave him a hand, removed the money decisions, the personnel decisions, all of the kind of structural decisions, and decisions that I would call travel decisions, that go into a modern campaign. If David would accept me, I would take that on." That's when the anecdote in the book, which I'll double back on, happened. I don't know if you remember that anecdote in the book, Clinton's own book, in which Clinton said to me, "Eli, I need you to go back there." And I said, "Bill, why me? I've lost seven times in a row." And Clinton responded by saying, "Because I'm desperate." I responded by effectively saying, "Okay, I'll do it," but what I meant to say to him and I think I probably did say this, "The one thing I'll promise you, Bill, is I'll do better for you than you did for me," because at that point, in the state of Texas, he had gotten us 29 percent and we had gotten 32 percent, which he disputes to this day. So he said, "Okay, you go and see if you can do better than I did in Texas." And we had a funny laugh.

So Wilhelm, I read him right. He very much wanted me to do this. Within days, not weeks, it became clear that I was the campaign manager. I recommended to David that we not change titles, that we had enough uncertainty in the campaign for me to become the campaign manager and for him to become the political director. I didn't need it as long as he made it clear to the staff how decisions were made, how people were hired, how decisions were made about airport one versus airport two, airplane one versus airplane two, which is the guts of the campaign. People think it's the grand strategies that determine the outcome, which they do in many cases, but—at some point I'll give you my theory of campaigns. I won't do it today.

Riley

Okay. I'll call you back on that.

Segal

By some time in February I had moved to Little Rock and began running the campaign.

Riley

Phyllis, did you go?

Mrs. Segal

No, I didn't move to Little Rock with Eli. We had responsibilities at home, including our daughter who was completing her high school senior year. We were selling our house in Wayland because our daughter was going off to college. And in addition to my work at that point as a mediator, we were building a home to move to because we were moving out of the home where our kids had gone to school. So I was involved in both my work and a major construction project, with which we merrily continued. Eli had been in so many losing campaigns that we figured he would do this, then he'd come back and we'd move.

Segal

Phyllis' advice, when I said, "Look, Phyllis, Bill has asked me to move to Little Rock. We've got this great house which we just bought—" just bought, not thinking about buying— "Clinton is never going to win, it's impossible. We've got Gennifer Flowers, we have the draft, we have marijuana, we have—" I don't know, I had two or three others lined up— "He's a certain loser, but my friend is in desperate shape." I still remember it. We were walking on Dartmouth Street.

Mrs. Segal

And trying to figure it out. And we said this is what Eli needs to do and we could manage. Both his business could manage him taking a break from that, and I could manage the move we were in the midst of.

Segal

And we said, "Okay, we'll do it again because this will probably last a month or so, and we'll be back and we'll go about our lives." P.S. 10 months later, the night of the inaugural, was the night we closed on this house.

Mrs. Segal

And every step along the way in that construction, Eli and I would check in with each other. We didn't want to jinx how well Bill Clinton was doing by calling off the construction and the acquisition because it was all going so well. So we just continued on those double paths and built a house we never lived in.

Segal

So from February until November I worked in Little Rock. I did virtually no traveling. I had, largely by my choice, virtually no day-to-day contact with candidate Clinton because I think—and this is going to be a little bit of my theory of politics—you really know a candidate by his ideas, not by the people he hires. Not by his communications, not by his skills as a politician, but by his ideas. It's overlooked. People think you learn a politician by some of those other things. I felt we had very strong people around Bill Clinton, on the airplane, uptight. I thought they were crazy and I tell this to them but as Hillary always used to say, she would take the A people. I would always take the B people. She would take the A people driving him nuts all the time, giving him more good ideas, whereas I would focus on the B people who would build good teams. She was right, I was wrong.

So during that campaign we had a very unusual campaign structure and we will never know if the traditional campaign structure would have helped him or hurt him. Our campaign structure essentially had four people on the top of it. It had on the top of it me as the campaign manager, Wilhelm as the political director, Carville as the strategist, and Stephanopoulos as the communications person. That was it. You can talk all you want about Stan, who was in and out of the campaign 12 times, and Greer. These are all my close, close friends, we had daily problems with the advertising agencies. You can talk about Mickey, who had very hard times with all the people in this campaign. The only people who came to work every day, who were sure of their roles, who knew what they were doing and had Clinton's abiding confidence, were the four I gave you.

Riley

Had Mickey wanted a more traditional campaign structure?

Segal

Yes. He wanted a more traditional campaign structure in which he was the campaign chairman. He couldn't have it because he had lost the confidence of the senior people in the campaign and the senior people in the Democratic Party, for whatever the reason, and that is well outside of our timeframe today. It became impossible for him to operate when he did not have the respect of his theoretical colleagues. It was a very hard time. The political campaign was the hardest time for me because here I was making decisions involving millions and tens of millions of dollars every day without really talking much to the candidate, without clearing anything with the chairman, and just doing it. I did it because I knew how to do it, I had done it in the past, and I knew there was no one in that campaign who could do it as well. But it was hard. It was a rough deal.

I'm going to stop here, except to say that that's as opposed to the next eight years, which were the eight best years of my professional life with easy access to the candidate, working on two of his four key issues. By the end of the campaign, welfare reform, AmeriCorps, economics—"It's the economy, stupid"—and healthcare were what he was running on. Now I had very little to do with economics and healthcare, I'll say, but welfare reform for the second term and national services first were two of his greatest triumphs, and he would say right now that being in the middle of that was really terrific.

Mrs. Segal

Back in the campaign, before you leave that, what you haven't described—and it may be that you're choosing not to—is the glue role of stopping people from killing each other. This is a historical record where there's an opportunity to describe that, without getting worked up about it though.

Segal

Well, the problem is it gets too personal. I have no idea what these guys already know, so I'm going to guess they know very little.

Mrs. Segal

Let me just stop and ask Russell, while you're relaxing, if he could describe to you the ground rules and then you could decide whether or not to move on to that. I think this is a good time for that.

Riley

Absolutely. What we routinely do, and we'll follow the same pattern here, is the words belong to you. We make a transcription of the recording. It will take several weeks for us to do that. The transcript is then returned to you, or to Phyllis if you choose, to review. At that point, if you want to edit the transcript or to place any stipulations concerning release, then you're allowed to do that. The reason that we created these ground rules is to encourage people to speak candidly on the tape with the understanding that if there are some things that are personal or sensitive, then that doesn't have to appear for whatever time that you feel comfortable with. If it's 20 or 30 years then we can do it that way.

Segal

Well, let me ask Phyllis and Arnie. Is there anything gained by my getting into all the Betsey Wright and Susan Thomases and Mickey Kantor stuff? Anything to be gained at all? It's now 13 years later.

Mrs. Segal

Can you talk about that in terms of your role more generically and the flavor of what was going on?

Segal

My instinct—Arnie shook his head no and my instinct is similar. I know Russell would love it.

Riley

Maybe I could phrase the question so you can see whether you feel there is some historical value in it.

Mrs. Segal

Eli, you could think about it and then we can go back to it. While Eli's thinking about it, go ahead and phrase the question. Eli, you don't answer it and that will help.

Riley

Of course. From the historical perspective, I think people who are not in campaigns often don't have an understanding of what the dynamic inside a campaign looks like and it would be very easy, even for close students of politics, to look at this from the outside and say, "Oh, this was a successful campaign, it must have been relatively smooth running." But unless you get in and start looking at the parts, you don't see where the friction is and where it's necessary to put oil in the joints to make sure that that friction doesn't overwhelm the good ideas.

As you've said, one of your theories of politics is that ideas ultimately matter and yet there have been a lot of—as you well know, you've worked on a lot of very good campaigns that had fabulous ideas that did not succeed. So I suppose we're not so much interested in the conflict or the dirt for its own sake, but rather to help us understand how people committed to the same vision and committed to the same person can have different conceptions of how to best go about achieving what they want and yet their own personalities sometimes tend to get in the way.

Mrs. Segal

And how a campaign is successful amidst that, keeping together, as distinct from letting it fracture the whole process.

Riley

Absolutely. And I think I could also tell you, from the content of the other interviews that we've gotten—and I won't belabor the point—there are two things that I will say about this. One is that you should know that you have great admirers among the people who worked in this campaign. I was reviewing some of the confidential transcripts on my way here today, which is something that we routinely do, and there are many people who were important in that campaign who said, "You know, the guy that you don't know about, that you haven't seen, that you don't hear from because he doesn't get out and there's nobody out there telling it for him, is Eli Segal. He was—" you used the term glue— "the glue that held everything together." The second thing is that of course we know that there were problems. Mickey had problems. He had been assigned to do the transition stuff and then ultimately that didn't—

Segal

He was assigned to do the transition step by me. The reason was to get him out of the mainstream of the campaign. It was what I thought a—I certainly won't call it brilliant—it was an elegant mechanism for giving him face and no role. That was it. No matter what you hear from anybody, that was Bill Clinton and Eli Segal, and no one else.

Riley

The only other piece of conflict that I remember—

Mrs. Segal

You'll plant this in his head but he's not going to respond. He's going to think about it.

Riley

There was a comment in a press account after New York that you and Rahm had gotten into a pushing match over something related to Clinton's schedule. If you examine the record closely, you get these little bits and pieces of things but not the overall picture. So let's shut the recording off now.

February 9, 2006

Riley

This is the second of our sessions with Eli Segal. To begin with, there were some odds and ends left over from yesterday that you said that you might like to address and maybe we should get started there.

Segal

I have two things that I think can bring my comments about the campaign to an end, subject to your needing more clarification. The first was when I knew the campaign was over, that we had won. It was surprisingly early. It was just after the Republican convention, within days. You might remember they had an awful convention. It was a convention dominated by the far right, by [Patrick] Buchanan, by [Marion "Pat"] Robertson, by Marilyn Quayle, even by the Vice President. They went way beyond the culture wars to attack Clinton, Democrats, Hillary.

The reason I knew the campaign was over then was not so much their words, which were stunning to me, but in the course of the next five days—this must have been in August—each day I got a phone call, direct and indirect, from a prominent Republican leader, announcing that they wanted me to know that they were going to make a six-figure gift, which was still legal at the time, to the Democratic National Committee. The call was always from somebody to let it be known to whomever was the highest-up person in the Clinton campaign that the campaign was over. I remember some of the names, not all of them. They included people like Augie Busch, the beer tycoon; Ernest Gallo, the wine man; Thomas Watson; Dwayne Andreas; and one or two others. One a day, it was like clockwork.

So when I was encouraged in those days by one of the many power centers in the Clinton administration to change political directors, I was appalled and absolutely refused, recognizing that one proposed political director might be superior to David Wilhelm. My basic position was, "We're winning. We are going to win. You don't rock the boat when you're going to win. We're going to see this out. The answer is no." It was a very important moment, both for the team—and Little Rock was aware of all of what was going on here—and for me, both before and after the campaign. But it was very important to establish that principle, if you will, that when you're ahead that's it. That was one very important moment.

The other moment I wanted to mention just in brief, as we got closer to the end, the excitement was palpable, that this is—we've got it. As we got closer to Election Day, I was asked not so much to organize but to speak for the team on election night when my friend Bill, no longer my friend Bill, was invited to our big election night party. And the person who was asked to chair it was me. It could have been many, many other people. First of all, it was a wonderful night. It was a night where everybody, both the campaign staff and the hundreds and hundreds of major supporters, came into town. I still remember my speech. I said, "You see all these people out here, Bill—I'm sorry, for the first time 'Mr. President,' and I know it's the last time I'm ever calling you Bill. These people all think they're having fun tonight because they won, but they don't know what it's like to win until you've lost seven times in a row." The crowd goes crazy. It was a really great moment. President Clinton, also having quite a substantial losing record, I think he won with Jimmy Carter, enjoying the moment as much as everybody else, going crazy.

The next morning on a much more select basis, the two or three hundred really important major players in the campaign—staff, funders, and politicians—gathered in the Excelsior Hotel and the person asked to make the keynote speech the next morning again, to introduce the President, was me. I remember that was a good speech, too. But I guess I wanted to say that it was an honor to—having been eight months ago in an apartment in Boston trying to decide whether I was going to go to Little Rock at all, whether I was going to buy a new house—to be in that position. We won and I was very happy.

Mrs. Segal

I want to just ask a question, whether anyone else you've spoken to has described either of those events. I was sleeping that morning so I can't describe it firsthand but from what I'm told, the Excelsior speech that Eli gave was amazing, that the standing ovation that he got was unlike anything that had been seen before. So I would hope, for the historical record, somebody who was there could comment on it.

Riley

I don't remember. It may very well be that in 65 interviews somebody has, but it plants a seed for me in subsequent interviews to be sure—

Segal

Well, certainly Sam Brown and Alison Teal were there. All the big funders were there. It's just a detail.

Riley

But an important detail.

Mrs. Segal

An important one and I was so sad to have missed it. That's why I want to see the history described. I was so tired I crashed.

Riley

I was going to ask you one question that may seem tangential here. A lot of people come to know about that campaign because of the movie that was done, The War Room, which was an unusual decision to take in the first place.

Segal

I was completely opposed to it.

Riley

Can you explain why?

Segal

First, when I got there the decision to do the movie had already been made. I always believed that it would become the Carville-Stephanopoulos movie. It would come out after the election. It would not do the one thing we were all in Little Rock to do together, which was win an election for Bill Clinton. And while I am today very friendly with James Carville, I have a little difference of opinions with George. I saw no reason to be elevating the star appeal of these two fellows, to be taking away one minute, much less probably hundreds and my guess is thousands of minutes, of valuable campaign time to be wasting our time talking about Brazil and all the other crazy places we wound up talking about in that film. So I just thought it was a huge waste of campaign resources. I wouldn't have wanted to be the person who funded that movie.

Riley

I'll ask you one more question about the campaign and then we should move on. You said yesterday that you had a kind of theory of politics. I'm wondering, from your perspective, if there were any broad lessons from the way that campaign was run or organized that are instructive for people who study campaigns from the outside.

Segal

I'm not sure I could do it on the fly like this, but I believe the fact is Bill Clinton brought a lot of new things to that campaign, but what he brought along mostly was not the war room. If we look hard, we'd find war rooms in earlier, in future campaigns. You're amassing information. What else are campaigns about? Amassing information that you're going to use against your opponent. But the idea of a Democrat talking about budget cuts, talking about middle-class tax cuts, talking about welfare reform—bold. Talking about universal healthcare. I'm going to say that there were others who talked about that before him, too, but he put that on the central burner. A Presidential campaign talking about national service, a brand new idea. The idea that Democrats, traditionally the party identified with rights, not with responsibilities, would be in the lead in talking about the need for citizens to give back. Brand new. And while you had to read about Gennifer Flowers, deep down the American people understood that he was talking about something new. It was remarkable.

Riley

During the transition period, we know the position that you ultimately took. Did you give thought to where you might like to go in the administration, or did your conversations with other senior people, including the President-elect, include discussion of your taking other positions in the administration?

Segal

My core feeling, as hard as it is to believe, is I always viewed my job as getting him elected President, and I had every intention of moving back to Boston.

Riley

You had a new house, right?

Segal

In a city we loved. And did we have a new grandchild already?

Mrs. Segal

Not yet. No one was married at the time. Jon [Segal] and Pam [Lehmberg] were living in our new house.

Segal

It was 1997.

Mrs. Segal

And they were married in '98.

Segal

Right. But we had sick parents. I loved Boston and I wanted to go back. I remember speculation in either Business Week or U.S. News that I was a possible candidate for Chief of Staff, and I said, "Somebody put that article in there who is not a friend of mine." It was a very hard couple of weeks. While at that point I would have probably welcomed an opportunity to work inside the White House, having worked inside a Clinton campaign, it was not a high priority. I knew what it would be like for my marriage, for my friendships, for my personal well-being. So I could never define a job that worked—and those who became the leaders during the transition, I'm talking about Warren Christopher and Vernon Jordan, couldn't understand this, and Bill Clinton couldn't understand this since I didn't spend that much time with the President-elect during the transition, but it's the truth.

During the months of November and December, as the jobs were being divvied up, everyone thought I was very unhappy that there was no job for me. I had a far more ambivalent attitude. I didn't want to be humiliated, which was a very popular word during the December-January period, and humiliated was an easy thing to be during that time. On the other hand, I never relished the idea of a job for which I didn't think I was qualified. The idea of being Director of Legislative Affairs, I had never worked in Washington—well, I had but many, many years earlier. Director of Political Affairs, same. So I was truly uncomfortable with the debate about me and, frankly, the debate about others.

Then out of the blue, two people in this room right now actually came up with an idea that was quite—first, bizarre and second, brilliant, and probably in that order. Arnie Miller and Phyllis Segal reminded me that I used to come back to them when I was on the campaign trail, the few times I went out on the bus, early, right after Bill Clinton came out of New York City with that fresh glow of idealism and youth, and I said to them, "You can't believe what it's like when Bill Clinton talks about what he calls national service. With all the great applause lines, 'It's the economy, stupid,' it's whenever he spoke about national service that it really got the crowds. You looked around and there were moments when you thought you understood why. You had people in the crowds who had served in the Peace Corps, others who had served in the Civilian Conservation Corps, others who had served under the GI Bill, and he was talking to them. It's not a usual way of putting an audience together." And I don't remember which one of them said, "Eli, you're an entrepreneur, this might be interesting." I said, "Nah, he's going to pick some social service geek who knows nothing about social policy and bury it. It's a nice applause line. It's not for me."

I cannot remember exactly how it went from an idea that they were driving me crazy on at the end of December, beginning of January, to something that someone—

Mrs. Segal

It was a meeting—you and I were staying at the Four Seasons Hotel and we discussed this the night before. You were going to have a breakfast meeting with Vernon Jordan. I don't remember the content of the meeting but you went to that meeting intending to discuss this.

Riley: So just to be clear, it was something that you had sort of proposed as a possibility through a kind of informal network.

Mrs. Segal

It was an idea that Arnie and I developed with Eli, and Eli proposed directly to—I believe it was Vernon Jordan. It wasn't filtered. It went direct to Vernon.

Segal

You have to understand a word about my friend, Arnie Miller. He wasn't just an ideas guy coming to me about another crazy notion, Arnie was Assistant to the President for Hiring, and I think there's a better title than that, for personnel in the Carter administration. He has since helped to build the largest hiring agency for non-profits in the United States.

It went to Clinton. The President embraced it immediately. He called me up the same day and suggested it. It was his idea. He said, "Wouldn't this be great? I've always been worried that this idea was going to get lost in the shuffle. Would you do it?" I said I'd think about it. I made some phone calls to those who were in the very small—we're talking maybe a half-dozen, dozen, maybe a couple dozen people—who were involved in the nascent national service world, and it sounded like my kind of thing. It was a start-up. We didn't do much biography yesterday, but I had been in a lot of start-ups in my life successfully. It was in the field of social change, where I had some experience, and it was something important to Bill Clinton. After a day or two of thinking about it, I said, "This is pretty good."

On January 15, five days before he took office, with still much uncertainty about who was going to do what in the chaotic pre-inaugural of Bill Clinton, the President organized a big press conference. It's the irony of that press conference that of all the hundreds of very important appointments he needed to make, the entire White House staff with the exception of the Chief of Staff, he named me and Wilhelm to our respective positions. I spoke before national audiences at a CNN [Cable News Network] event. It happened the day of my 50th birthday. We have the remarks somewhere.

Mrs. Segal

I have the C-SPAN [Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network] tape.

Segal

I would say from that day until Bill Clinton left office were by far the eight best years of my life professionally.

[BREAK]

Mrs. Segal

I would just say that the other thing that was perfect about the national service mix, in addition to Eli's history as an entrepreneur, is that throughout Eli's life he's been a pied piper to young people. I think that the whole experience of leading the creation of national service with young people—and all you have to do is go to the website that we've created for Eli where many people who worked with him are telling the stories about what it was like—confirms that pied piper magnetism to young people.

Riley

The website address is?

Mrs. Segal

It's Caring Bridge, www.caringbridge.org, and the entrance is Eli Segal, "elisegal" as one word. You'll see a lot of the people you interviewed giving remarks. In fact, Sylvia Mathews talks about some of the things she said during her interview that brought back memories of Eli.

Riley

Well, yesterday when I mentioned people emphasizing the role that you had during the campaign, Sylvia's interview was certainly one that prominently featured. So given the fact that she's already mentioned that, I'm not divulging something out-of-school here.

Mrs. Segal

Do you feel okay to go on?

Segal

We have two big things to do yet. We have AmeriCorps and Welfare Reform, and a limited number of minutes.

Riley

Let me pose one question that might help expedite things. There is a book written by a guy named Steven Waldman called The Bill.

Segal

If you've gone through that book you know at least a good deal about the legislative history of AmeriCorps.

Riley

In your judgment that's a reputable book.

Segal

It's 80, 85, 90 percent accurate. I can't tell you where it's not accurate right now but it's a pretty fair reading of the history.

Mrs. Segal

In terms of verifying the history, there are probably two people who worked closely alongside of Eli who could make whatever corrections, and they are Jack Lew and Shirley Sagawa. Am I right in saying that?

Segal

Maybe you've interviewed Lew.

Riley

Jack we've interviewed before and Shirley we have not but I think under the circumstances, Shirley ought to very much be on our list.

Mrs. Segal

They'll be able to point out where The Bill is missing the facts so Eli doesn't have to go through the linear—

Riley

Absolutely. That wouldn't be a good use of our time. I understand you've got a couple of good stories that are supplements to how you managed to get this bill through. There are two pieces of the AmeriCorps story. One is getting it on the books and the second one is the actual implementation. If you've got enough energy to tell us—

Segal

I'll tell you one really good story and that may trigger more. Congress was very split, then as now, with Democrats in the majority. I think it was 53-47. We had worked very hard. I had really worked the House side, which had a big Democratic majority, and we were going to win on the House side, it was clear. I had done something that had not been done by any of my colleagues in the Clinton administration, working the House side by going door-to-door to House Congressmen who had never seen a Democrat before, asking for their vote and getting a lot of them. I got a lot of commitments under the general leadership of one Republican named Chris Shays and another Democrat named Dave McCurdy from Oklahoma, who were very helpful in saying, "Go to this one, go to that one, this one's lined up," et cetera. They just wanted to see that I was real, that I didn't have horns, that AmeriCorps was not about creating a new Democratic cadre of young people but was about helping our country in a time of great social need.

The House—there's a lot of tricky stuff, but the Waldman book gets it very well—was essentially a done deal. The Senate was going to be the battle, and to get it through the battle involved first the support of Nancy Kassebaum, who would go only so far. She would not do enough to move her caucus in the direction that we needed to claim a victory and so we came up with an alternative strategy, which was initially just to get one more vote but then became something more than that. The Senate Majority Leader was Bob Dole. His wife was the president of the American Red Cross, one of the traditional homes of volunteerism in our country. I was very brazen in those days. I've since gotten older and probably even more brazen. I said, "The only way we're going to get the Republicans is if we get Elizabeth Dole." They said, "What, are you crazy? How are you going to get Elizabeth Dole?" I got her on the telephone and I said, "Mrs. Dole, may I come over and see you?" She said, "Of course. No one calls me up from your side. I'd love to see you."

I'll never forget that lunch, which was across the street from my office. She was dressed to the nines, the way she always is, and her team similarly was dressed—I don't want to say the 1950s, that would be a slap—it was very traditional. And all of the people who were waiting and waitressing were also from another era. We sat down to have lunch and I said, "Mrs. Dole, I'm Eli Segal. I'm not here to talk to you about the usual Clinton initiatives that split America. Things that Bill Clinton believes in are right, many that your husband believes in are right. I'm here about something that we all should agree on, the idea of mobilizing the power of young people to give something back to their communities." "Great. I love it, Mr. Segal. How could I be helpful?" I said, "Well, I'm the Assistant to the President for—" there was no name to it then— "the National Service. We're going to get young people, when the levees break, to clean them up. We're not asking what their party is. They're going to clean them up. They're going to be a great ally for you. They're going to be a great vehicle for you and other great organizations like you to fix America in a time of need."

She probed me hard about how it would work and I explained to her what the legislation would do. She said, "That's really, really good." I said, "But it's not going to work, Mrs. Dole, unless you're going to support it." So we went back and forth in that usual way that you start jockeying over support, not support. Finally I said, "You know we need your help." She said, "Well, you've got my help, Mr. Segal." I said, "No, Mrs. Dole—" I think it was very formal. I'm not sure about this, she may have started calling me Eli, but I stuck to Mrs. Dole— "We're not going to get it without you, and the only way we're going to get it with you is if we get a written statement from you that this is something you believe in." "Well, I can't really do it." I didn't mention her husband's name, I didn't say a thing. "We can't possibly get this done without you." And she said, "Well, at least give me the night to think about it." And I said okay.

The following afternoon, late in the afternoon, I called her up and said, "Mrs. Dole, this is the moment. We're moving forward. Can I have your support?" She said yes. Needless to say, we ran over there in a rush, writing the statement as we were walking. I think it must have been raining out. It was one of those classic moments in politics. You're never really quite sure what's coming down. Now you must understand I did this without the knowledge of anyone in the White House because they would have had 50 different spins on why you can't do this. I was just going to do this, which is the entrepreneur, I guess. I got her to sign the piece of paper, and then of course I immediately picked up the phone and called—I don't think it was Johnny Apple, I could get you the name of the reporter—but it was certainly on the front page of the New York Times the next day.

The next morning at 7 o'clock, maybe earlier, I get a phone call from the President of the United States, "Eli, what did you do here? I got Bob Dole on the phone saying, 'Who is this guy Segal? I never heard of Segal in your administration.' All I know is Dole's hopping mad and wants to see you immediately." I explained to Clinton what had happened and I think Clinton was laughing, I don't remember those details. But I went down to the Senate Minority Leader's office and I walked into the office. They ushered me right in. It was the fastest trip in. Usually they sit you, they serve you coffee, they do this, they do that. "Hey, Segal—" that's the first line out of his mouth, not anything other—I did then and to this day, I think he's a great guy. "Hey, Segal, they say you know how to count votes but you've got it wrong here. You've got the wrong Dole." [laughter]

This led to a day or two of really extraordinary vote counting back and forth, by which point I did have the White House engaged. Dole had eight different ways, maybe ten, to save himself, not humiliate his wife, and to give Clinton the win. The White House probably would have taken what he had proposed a few days earlier, but realizing that we had him on the run now, wasn't going to take it any more. It was about the amount of money that would be authorized for the program. We now were going to be bullish and were going to insist on our own, maybe a little too cocky, but in fact that's the way we went. I finally said to him and his chief aide, named Sheila Burke, "We can't do it, we just can't. I've pushed this far." She pulled some tricks that, frankly, if it hadn't been for Jack Lew sitting next to me, could have been terrible. What do I know? I'm from Boston. I'm a businessman. Who knows the difference between appropriated and authorized? I had no idea, but he was by my side. It was great and we were able to get a really, really good provision—which didn't mean it became the law of the land. That leads to the other legislative story.

Mrs. Segal

There are at least one or two other legislative stories but let me just interrupt. [requests break for oxygen]

[BREAK]

Segal

We were still not sure of victory. I can do this quickly because I think it's in the Waldman book, how we finally won with the help of a very brave [Lincoln] Chafee of Rhode Island breaking the filibuster and then a group of them caving in after that. We succeeded. I really can fast-forward because it is all in that book.

Mrs. Segal

Do you want to tell the [John D.] Rockefeller baseball story and then the Teddy Kennedy story?

Riley

I'd love to hear the baseball story. We saw Fenway when we were driving in yesterday and my only regret was we didn't do the interview at some point during baseball season.

Segal

I don't have it exactly right and I don't know if Waldman's got it, but the essence of it is that there were two Democrats who were reluctant to support what Bill Clinton was beginning to call AmeriCorps. It hadn't officially been named yet. One was Bob Kerrey, who I think ultimately may not have voted for the legislation, and the second was Bob Byrd, who was just opposed to one more spending package.

I went to see Jay Rockefeller, a fellow Senator from West Virginia. We didn't always get along but we did a little vote swapping. I walked into Rockefeller's room, in which I'd never been, and said, "Jay, we need Bob Byrd's vote." He said, "He's very hard to get." I said, "But I'm told you can do it," my usual line. Then we started chitchatting about things. I looked around his room and I could see that baseball was a very important part of his life. I said, "Jay, I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I'm going to let you off the hook easy. You ask me any baseball trivia question you want, whatever. If I get it right, you've got to ask him. If I get it wrong, you're off the hook."

This is where my memory fades a little because this is 12 years ago. I think his first question was, "Who was the organist at Ebbets Field?" I said, "Everyone knows that was Gladys Gooding." He had a chuckle about it and then he said, "Everyone knows that in 1950, the Giants effectively won the pennant by getting Eddie Stankey and Al Dark from the Braves, but no one knows whom the Braves got in return. If you can tell me who the Braves got from the Giants, you win." Who could remember a piece of trivia like this? This is a trade that had happened probably—let's see, this was 1993 and that event happened in 1948 or '49. Without hesitating a second, I said, "Everyone knows it was Willard Marshall and Sid Gordon." [laughter]

It blew him away. It created a friendship, although I don't think he remembers that that's where our friendship comes from as well as I do. I was right and he delivered Bobby Byrd. Now whether that was a direct one-on-one I'll never know, but it was Rockefeller doing what he said he was going to do, and my using the last bit of skill I had. I knew baseball and politics pretty well.

Riley

That's a wonderful story and it's the kind of piece of history that would just be lost unless we had a chance to record it, so thanks for letting us get it.

February 10, 2006

Riley

This is the third of our interviews with Eli Segal. Mora says there are a couple of things left over from AmeriCorps yesterday that you wanted to tell us about.

Segal

I want to tell you one story about Bill Clinton, one about Ted Kennedy, and two about me on the road. This is a great anecdote that I don't think is in Waldman's book. It was shortly after the 1994 revolution. The Republicans were in full assault on everything related to the Clinton agenda, one of which was AmeriCorps. I'll never forget the moment when Newt Gingrich said to Bill Clinton, "AmeriCorps, that's history. It's out of here." Now Bill Clinton, who frequently is accused of being spineless, responded to this direct challenge to AmeriCorps by first, making me an honorary member of the Cabinet the night of the State of the Union in '95, and second, putting four young AmeriCorps members, the first year of the program, into the balcony with the First Lady, all wearing their AmeriCorps outfits. That was his response to Newt Gingrich, a bold commitment to the continuation of the program. Did you know that story?

Riley

No, I did not.

Segal

From that point until '98 we always knew that AmeriCorps was safe, that no matter what appropriations bills were sent up to the House, it wasn't going to be eliminated. And he was true to his word. Every time it looked as though there was going to be a veto, whether Clinton was going to be moving in order to get through his HUD [Housing and Urban Development] bill or his Veterans Affairs bill—the reason I mention it to you is it was a very big charge to be added to the Cabinet that night and it must have been for personal reasons, apart from our personal story. I remember chitchatting on the floor of the House with Bill Cohen and Arlen Specter, who were kidding and teasing around with me but understood they were wasting their time.

The second is another story you probably don't know. I mention this story out of all the stories because Ted Kennedy is so much a part of the Miller Center with his own oral history. All during the legislative battle back in 1993 there was a funny routine. Every night the phone would start ringing around 11 o'clock and the person on the other end would ask, "Did we call this person? Did we call that person? Did we take care of this business? What are my marching orders for tomorrow?" And the questions were coming from Teddy Kennedy. I don't know any other United States Senators—who are inclined to be prima donnas—to roll up their sleeves and essentially work for Eli Segal. It was Teddy Kennedy calling those nights. There were other great moments during that time, but I mention this for you to get maybe a slightly different perspective on the Senior Senator from Massachusetts, who has been, from that period until now, my ideal of a good public servant. So those are my AmeriCorps stories while in Washington.

There are two stories I must tell you about things I saw. I'm going to assume you know the numbers in AmeriCorps, that it's grown from a tiny program—

Riley

Yes, sure.

Segal

Bill Clinton is proud of saying how it's now ten times the size of the Peace Corps, as he should be. But my last two stories are not about Washington. They're not about Bill Clinton and Ted Kennedy. They're about how AmeriCorps changes America. You know, we all have this inchoate sense, on my side of the aisle, that AmeriCorps must be good, but I saw it. In October of 1994, we had just passed the legislation and I was trying to build public support for it and I was asked to take a trip to Philadelphia. Late in the afternoon, maybe 4 o'clock on an October day, I'm strolling down the streets of North Philly with around eight or ten members of the press corps from Philly, local and others. Big crowd. But my press secretary said, "Okay, the event is over, that's it."

I keep on walking and a man comes up and taps me and he said, "Mr. Segal, you don't know me. My name is Mr. Ryan—" African-American— "You don't know me but I'm now a ward committeeman here in town. I've been active here in the Democratic Party a long time. Sixty years ago I was a member of the Civilian Conservation Corps and from that moment until today the idea of giving something back has been at my core." I said, "Mr. Ryan, come with me." We walked about half a block to a place where an AmeriCorps program called YouthBuild was operating—it's a rather unusual AmeriCorps program, largely black and Hispanic—there were five young people, black and Hispanic, three men and two women. As Mr. Ryan walks into the house, I walk up the stairs. They don't know me from anywhere, I'm just another white liberal. They're banging away—that's what YouthBuild does, they build houses.

I had said no more than ten words and I reached this point, I said, "This is Mr. Ryan and 60 years ago he was doing the exact same work as you are doing now." With that, unrehearsed, Mr. Ryan reaches into his pocket and pulls out his wallet. He holds his wallet up to show his Civilian Conservation Corps card to these young people and he begins speaking about what the Civilian Conservation Corps meant to him, where he went, what kind of citizen it made him, where he was going in his life until then, and where it was going to take him now because he had joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. It was a very compelling moment. You knew that the five young people's lives had been changed more fundamentally than could be described by any words that could come out of my mouth. He finishes his little speech, which was terrific, and the kids, who had probably never been outside of Philadelphia, I'm sure they never had been, ages 17 to 19, you just knew that that mesmerized look was because of the dynamic of different kinds of people working together for common change.

Mr. Ryan came back in my life a few other times. When we had a couple of farewell parties for me, the First Lady once brought him down to Washington for kind of a little reunion. It was very nice. But that moment for me was what AmeriCorps was about. If we had time I could tell you stories like that until tomorrow.

Mrs. Segal

[suggests resting break for oxygen]

Segal

I'll tell you one more story. This was a story about an AmeriCorps program in McAllen, Texas, probably the poorest city in the United States, on the Mexican-American border, where most Americans don't have toilet bowls. Very poor. I was there for another one of the rituals of AmeriCorps, swearing the young people into AmeriCorps. It was a great group, also a little bit different in that it was composed solely of honor students in high school, all Hispanic because that's all that lived in McAllen, Texas. It's quite a nice little ceremony that we do and as we're doing it, the kids are responding with great enthusiasm to my words. As I finish, I look around at the faces—not of the kids but of their parents, dressed in their finest uniforms for this visitor. Not a dry eye in the crowd, everyone in tears.

Scratching my head, I said. "Why this kind of emotional breakdown?" I had no idea so I started asking questions. I said, "How many of you would have gone to college without AmeriCorps?" Not a hand went up. "How many of you are going to college because of AmeriCorps?" Every single hand shot up. Good kids who were denied what all of us took for granted but for the passage of AmeriCorps legislation. I actually kept up with a few of the kids for years thereafter, not in the last few, and they explained this to me. We forget AmeriCorps, we think, Oh, $4,700, what does that get you when you want to go to Harvard? But $4,700 pays for a full four-year, fully loaded college education at McAllen South Texas Community College, or University of Texas-Pan American, whatever the college was right there, you get a full ride. I remember thinking, You know what, this is pretty good stuff. So those were just two of the many stories I could tell you about what AmeriCorps does.

I'm going to take a break now for five minutes.

[BREAK]

Riley

Eli, were there occasions when you convinced President Clinton to participate in some of these AmeriCorps events?

Segal

I'm not sure whether I convinced him but he did participate on several occasions, both AmeriCorps events and—one of his great prides was CityYear, which is the largest AmeriCorps program in the United States. He was never quite the same, I never saw him in other events—well, I take that back. He was a great performer so he always rose to the occasion, but he loved the young people and he loved their stories of transformation. I actually helped organize one event involving a discussion of how they went to crack houses and then ended a crack house. So, yes, I was involved. I said, "You're never going to get this, Mr. President, from behind the desk," and he understood that.

There was a cute story about that Mr. Ryan. Shortly after that day with Mr. Ryan and a few nights before the election of '94, I had dinner with Bill Clinton. I told him the story about Mr. Ryan and YouthBuild and, as is his fashion, the tears start coming down his face. He said, "Did you get that on film?" [laughter] It was classic Bill Clinton. He was deeply engaged in the program from the beginning to the end in every way, shape and form; the drafting of the legislation, he was all over the drafting. Some of the key decisions were his, not mine. Anyone who should ever suggest that this wasn't his legislation or his program is being historically inaccurate by 180 degrees.

Riley

Eli, you began to phase your activity out there?

Segal

In 1995, towards the end, it became clear to me that AmeriCorps had become effectively an albatross around his neck because it was so identified with him and because I was such a symbol of him and his Presidential candidacy. I went to him and I said, "Mr. President, there are other things I can do for you but I can't do this for you any longer. I recommend—" and the record will be clear on this— "that you choose someone, a prestigious Senator, ideally above the fray, to run this program. It's up, it's off the ground. The program is solid. It should be run by someone else."

He asked if I had any ideas and I said I did. I said I thought Harris Wofford, the soon-to-be—no, already now the former Senator, so this had to be after November of '95 when we had this talk. I would say it was—I'm going to guess now—December '95 or early in '96. "There will be other things for me to do," I said to the President and he agreed completely. He and I and Erskine Bowles, who had become Chief of Staff, made it so that Harris became the second CEO [Chief Executive Officer] of AmeriCorps.

Riley

And at that point you began doing some other things for the President?

Segal

No. In fact, for a few months I chose to take a little break. I did some assignments, did some traveling for him, but I got involved with a group of people, a fellow who had started a private equity business and became a member of the group. During the first part of '96 my life was spent learning and understanding the private equity world a little bit, but I was restless. I didn't want to do that. It was while I was in Washington. So by the early spring, I went to the White House and actually resigned as Assistant to the President for National Service. I had already resigned earlier as the head of AmeriCorps, with the understanding that I was ready, willing and able, as the campaign was getting closer, to become engaged.

As a matter of law, having played the role I did in the '92 campaign, I couldn't be involved in the day-to-day operations of the whole thing. It must have been, however, in the late spring that I got another one of those famous Bill Clinton phone calls, "Hello, Eli—" [imitating Clinton's Southern pronunciation of Eli] I always knew those calls meant trouble— "Eli—" And the President says, "I'm worried, as I always have been, that these guys are going to label me the ultra-liberal, tax-and-spend Democrat. Let's do what you did for me in '92 when you were managing the Presidential campaign. Let's create something that insulates me from the charge that I'm a tax-and-spend liberal." It must have been in March, maybe April. Clinton, you remember, had a walk-in nomination. Dole had to fight a little bit but it wasn't too hard. So I came up with, the campaign came up with the idea of creating Business Executives for Clinton-Gore.

The original idea was just to trot out the names of a lot of CEOs and major companies, but the President thought that was a mistake because it was limited. He called me to the White House—I don't think we met in the White House, we met somewhere else—and he said, "It's not enough to get people to silently raise their hand and say they support me. Let's come up with some more imaginative ideas." One of the ideas that someone came up with, I can't say it was me, was to have everybody who was going to endorse him not simply endorse him for reelection but make a commitment on their own that they were going to do something for their country, too. The idea that we came up with is that every businessperson who wanted to endorse him had to commit to hire a welfare recipient. That was it, a simple idea.

From launch until the big event we had in Stamford, Connecticut, we got about 350 prominent CEOs. They took the pledge at a very funny, raucous event in Stamford, Connecticut. It was raucous because no one really knew what they were doing there, and getting them all to commit to hire a former welfare recipient—but they did. They understood why they were there and the message was out. Shortly before the legislation hit the President's desk on welfare reform, he had gotten the business community or at least part of it to commit to welfare reform.

Riley

Eli, did the President ask you or did you consult with the President about the wisdom of signing the welfare reform bill? There were a lot of people in your natural constituencies who thought that that was a terrible idea.

Segal

I was one of the many who, when asked, told him I thought it was a bad idea. With the benefit of hindsight, I definitely believe he was right and I was wrong, and I would tell all my friends from the DLC and other constituency groups maybe right of center in the Democratic Party that this was what we needed. And the reason I can say it with such conviction is what happened afterwards with the creation of the Welfare to Work Partnership.

So we're now marching through '96. I had this little project that wasn't so little that created Business Executives for Clinton-Gore. The election was held, a great victory for the President. We weren't sure what we were going to do. Phyllis had a prominent role in the federal government. I had no job, not that I needed a job, I really didn't know how I might fit in. I got a call—I'm now talking right after the election. It's December of '96 and I get a phone call from the President's secretary, my very good friend Betty Currie, the President wants to see me. Please come to the Cabinet Room at a certain time.

When I went to the Cabinet Room, it was Bill Clinton at his mesmerizing best. He had, sitting in the room, five or six Cabinet Secretaries and five or six CEOs of the largest companies in America: United Airlines, Sprint, Monsanto, UPS [United Parcel Service], and two others. He goes around the room and he asks each one of the companies what they are doing on welfare reform, what they are doing about hiring. He makes this incredible plea that he and our government did their part, whether you like the legislation or not. We signed the legislation that time-limited welfare so no one could stay on the rolls for more than five years, day in and day out. Our government had done its part, the private sector had to do its part, and he really laid down the gauntlet.

The meeting comes to an end and Bill Clinton and everyone looks around, great meeting. No one knows what happens next so everyone starts shuffling out. He comes over and taps me on the shoulder and says, "Eli, will you come into the Oval Office for a minute?" I said to myself, "This is not going to be good." He says to me, "You know, Eli, you are really good at organizing things like this. Can you help me get the business community behind this?" So we're in the Oval Office now and I throw out an idea or two to him. He said, "No, no, you don't understand. I want you to take responsibility for this." And I said, "I really can't do it, Mr. President. I have children in Boston, Phyllis and I have just finally decided that while Washington was a great experience, it's not where we want to be for the next four years, and we thought we were going to go home." That was the end of the conversation. The next morning I get a phone call from Erskine Bowles, "Oh, the President is so happy you said yes." [laughter] True story.

The part I wanted you to know, there's a book I wrote with Shirley [Sagawa] called Common Interest, Common Good, which will give you a little of this, but I will tell you a little bit about the origins of Welfare to Work. The bottom line, the Welfare to Work Partnership was a huge, huge success. We went from nothing to over a thousand companies that didn't simply pledge to hire people but in fact hired 1,100,000 people in the course of a year, all of which is documented—who they hired, what kinds of quality jobs they had. What happened is—it's the reason I became such an advocate of welfare reform—it became clear that rather than the welfare queen, the stereotype that we had all grown up with, the people who hated the welfare rolls the most were those who were on the rolls. It wasn't nice people like Bill Clinton or Newt Gingrich, it was the people who suffered every day.

In any case, I went back to the President and we had a series of important discussions about how we might launch something like this, and did we want to do it inside the government. I was stunned that you didn't know, that welfare wasn't part of your research, and that's because we decided not to do it inside the government. It was too polarizing. We thought of doing it in the Commerce Department, for example. I told him that I thought the best place to do this was outside of government, something he called for that the business community responded to. He liked the idea. It was a few days before the State of the Union and I said, "The only way we're going to get this done right and big is for you to announce its formation in the State of the Union. Would you do it?" So he was back and forth about what goes into the State of the Union. It didn't take him long to say yes.