Transcript

Martin

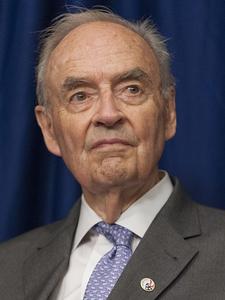

This is Paul Martin from the University of Virginia. We’re here with Senator Harris Wofford to do an oral history of his time both with the Clinton administration and his Senatorial career as well. Let’s identify ourselves to the transcriptionist so she can figure out who is speaking.

Chidester

I’m Jeff Chidester, research director for the Clinton project.

Wofford

I’m Harris Wofford, at my apartment in Foggy Bottom in Washington, D.C.

Steiner

I’m Jessica Steiner, a research assistant for the project.

Martin

Let’s start with your very first interactions with Bill Clinton. You mentioned that it was probably when he was head of the National Governors Association.

Wofford

Memory is very tricky. I could well have encountered Clinton before the Governors Association session in Cleveland in ’87 or ’88, but it was while I was Secretary of Labor and Industry in Pennsylvania, which began when [Robert] Casey won the Governorship in 1986. I’d been full time party chairman for his campaign, and I thought I was going to be the head of the Governor’s Office of Citizen Service, which Casey had promised we would set up after the election, to make Pennsylvania a model state of national service.

In the late ’70s I had initiated and then co-chaired with Jacqueline Wexler the Committee for the Study of National Service. We had produced a report that was generally, in the service world, considered a landmark proposal for large-scale national service. That’s the

green

book we produced with an interesting group of people, including the revered Father Ted Hesburgh, long-time president of Notre Dame and Lyndon Johnson’s Secretary of Labor [Willard] Bill Wirtz. Our report,Youth and the Needs of the Nation

had gotten a lot of attention, and it helped inspire the Democratic Leadership Council to come up with their own proposal, Citizenship and National Service, which they did in the late ’80s. Again, I’m not sure of the date, let’s say ’88. It was published when Senator [Samuel] Nunn was head of the Democratic Leadership Council, then Governor Clinton had been involved in it, and as head of the DLC he carried the torch for it.So when Governor Casey persuaded me to be Secretary of Labor and Industry and formed the Governor’s Office of Citizen Service—which became known as PennServe, based in the Department of Labor with its substantial resources—and Casey was about to go to his first Governors Association meeting, we got the idea that we should get the Governors Association to do a taskforce or a working group on national youth service.

We got Governor [Richard] Celeste of Ohio and Clinton of Arkansas—again, he may have been the Chairman of NGA that year—and Casey to propose this, and it was approved. So I was there to help staff him for the national service part of the Governors meeting. A half dozen or more Governors came to our session and a dozen or so joined it. A number came and gave little speeches. Casey did and then left. Clinton was late, but he came, with gusto. He gave a not short opening talk about his own experience with youth and national service. He had been on the Carnegie Commission’s

A Nation at Risk

report, I believe it was. It may have been a more focused one on middle school students or secondary school students. It was a very significant study, and he had been on the study group and one of the signers of the report, which called for all secondary school or middle school students, as a key part of their curriculum, to engage in service learning, to serve in the community and learn citizenship by doing it.He became convinced that it ought to be required in the school system—not by the federal government, because it doesn’t have the power to dog—but to be encouraged by the federal government. He thought every Governor should move to see that every student—in some form, not in any one prescribed form—should be required to have substantial experience in service in the community, working on problems and thinking about them, and talking about what they learned in their classes. He was very eloquent about that.

He had received our report

Youth and the Needs of the Nation.

From that very first meeting, he talked about how he had read our report and liked it. That was his speech. And he didn’t leave. Every other Governor, including the convener, Casey, stayed briefly after their speech to hear another Governor, and then left and went to their other business. Clinton had to be dragged away about two hours later. He was probing everybody. He was giving his own experiences, his own ideas. It was an extraordinary experience.He listened very well. I think he probably does that when he goes around the world now. Whether it was the Presidency or other things, I don’t think in his later Presidential years he demonstrated this magical ability to listen—to convey that he was more interested in what you had to say or what you thought than in what he was saying. I find now he monologues more than he did then. He was full of enthusiasm and therefore talked a lot, but he really listened.

I can’t believe he has this tremendous hold on and appeal to people around the world, of all ranks, if he doesn’t now have the energy for that kind of listening when he continues his extraordinary role as the best ex-President we’ve ever had.

Martin

When he gave the speech, was your only interaction with him as an audience member?

Wofford

No. It was just around a table, and he knew I was one of the ringleaders. When the Governors left, their staff people stayed. Each of them had a staff person designated for this working group. It’s the way they function on many things. The staff always assumes that’s the way it should be. After the principals go, now we figure out what we ought to do here. I think most of us were expecting that. I’m sure I wanted the Governors to stay. Probably everybody wanted Governors to stay, and he stayed.

Then I would meet him on different occasions on the political rounds. One time was the Democratic Convention in Atlanta in ’88.

Martin

Where he gave his speech.

Wofford

Yes, where he gave the long speech. We arranged for the platform committee (or whatever they did for issue forums), to have an issue forum on the Democratic Leadership Council’s proposal, and our proposal, on national service. We had a panel. I remember Bob Kerrey was on it because, to my amazement, I had thought of him as a sort of national service Democrat, and he came opposed to national service. He was one of the few Democrats who initially voted against Clinton’s national service bill. He changed his mind later. But I saw Clinton there at receptions and conferences, and every time I saw him, he immediately picked up where we were last—gave new ideas, asking what’s up, and is my staff really working and helping you? It wasn’t sporadic; it was as if it was a continuum of a conversation. It was extraordinarily pleasing, seductive, impressive. I’ve had that happen with him on other fronts like race and civil rights. Those we started later, but the first on national services was that kind of encounter.

With the tragedy of John Heinz’s death in the airplane crash in the spring of ’91, I had the opportunity to be appointed Senator for six months until a special election could choose the successor to Heinz for the rest of his term. I ran and I won. I took the gamble of picking [James] Carville and [Paul] Begala as campaign party chair of the Democratic Party. I had been on the selection committee that had selected this relatively unknown James Carville to be Casey’s campaign manager for his ’86 gubernatorial race, and he remained a key advisor of Governor Casey. So he was in the vetting of me for selection for the Senate.

Martin

So you in effect chose one another, or at least had some input.

Wofford

Well, it may have come to that. He was enough of a wild man that it was actually a risky decision from my point of view.

Martin

Can we jump back a little bit? The story you tell about Clinton staying at that Governors Council meeting and asking questions and interacting with different staffers. Most of the Governors came and then left, or did they show up and leave one by one?

Wofford

One by one. They didn’t all come at the beginning, and when they came they made their speeches.

Martin

Did you get any impression from that how other Governors, both Republican and Democratic, saw Clinton?

Wofford

I had the impression that his charm was contagious. I learned later that Casey did not take to him.

Martin

Is that right?

Wofford

From the very beginning. He thought he was a show horse. Casey was not as at ease with people. He was very stiff and somewhat shy. He was very strong in his opinions when he talked, but he wasn’t a

hail fellow

type. And Clinton was the extreme opposite: touchy, holding, looking you in the eye, trying to get the intimacy—of your mind, at least.I asked one of Casey’s top people,

Why did Casey take a bad view of Clinton at that very first meeting?

He said,I think the critical moment was in an elevator. Clinton was either talking to a woman in the elevator or talking about a woman in a way that made Casey think he wasn’t necessarily a very moral man. He didn’t like the way there was a cruising sound to the conversation, and it stuck with him.

Allegedly—this is not first-hand evidence I’m giving you.I was one of his Cabinet members then and a good friend from Covington & Burling law firm days. We were young associates together. I was somewhat older, but we overlapped for two years back in the mid ’50s here in Washington. He came down from Scranton, sort of idealistic, ambitious, not very at ease talking to people, and very upright, a good Catholic boy. He was a star basketball player at Boston College, and he was a very serious Catholic.

When I was trying to get him to support Clinton for President, he said,

You know, there are rumors about his behavior, sexually—

This is later when I supported Clinton for President. He said,There may be things in his closet, and I’d be a little worried about that.

The Casey-Clinton-Carville triangle became a very significant political factor. There was a skit put on for the Pennsylvania press corps. David Stone, the Governor’s chief of communications who later was my chief of communications on the Senate staff, did a wonderful, wonderful skit in which Casey played Casey. He was at his dinner table with his family and said the blessing and was very stiff. They were very respectful to the father, and then someone called and said,

There’s a message you need to take in the other room.

He opened the door to the other room, and Casey—you never saw him without his coat and tie—took off his coat, and people were dancing around like this, and James Carville, dressed up like a devil, was telling him to come in. Then Casey would get back in the video and go back to the dining room table. The video was suggesting a pact with the devil, that Carville was the devil. By then he was already famous with the Pennsylvania press corps. It was a very successful video.Carville was in on vetting people to be picked for the Senate seat, and I think he was the engineer of the idea of offering it to Lee Iacocca. He supposedly wired it all so that Casey would fly out to Iacocca in Detroit and offer it to him. It was supposedly wired that he would say yes, and it would be a great, shocking thing, because nobody thought that [Richard] Thornburgh—who already was the Republicans’ pick—could be beaten. Thornburgh was almost forced to leave the Attorney Generalship to reclaim this seat. There hadn’t been a Democratic Senator for 29 years, I think—Joe Clark’s reelection in ’62 was the last Democratic Senator until this seat came open. Iacocca, to Casey’s shock—because it had already been leaked to the press that he was doing this—said,

I need 24 hours to think about it.

There were 24 hours when it was the big story all over Pennsylvania that he had offered it. Then Iacocca turned it down.At that point, Casey put me in the running. A lot of people had been pressing for that, including his wife, Ellen [Casey]. He said no; it had to be a rich, young western Pennsylvanian, because he was dead tired of raising money, and he knew nobody would give money to what they thought would be a losing campaign. It had to be somebody who had his own money or could get it, from his point of view. The person had to be young, because if anyone, by chance, could win the seat, they could keep it. And only a western Pennsylvanian could win, he thought—someone from Thornburgh’s own territory to have any chance. Iacocca wasn’t from the west. He was rich, but he wasn’t young, and had been outside Pennsylvania for a long time. So Ellen in bed allegedly was saying,

Now why not Harris?

She had been lobbying for me. I was vetted by the general counsel, his own great lawyer friend, and James Carville, whom I knew.Let me give you one vivid little example of this vetting. It relates to Clinton. Carville asked me,

Did you ever smoke marijuana?

I said,Well, James, I have to tell you honestly, I’ve never smoked cigarettes in my life. I’m embarrassed by my lack of sense of sin about smoking cigarettes, but I never smoked. I did try, but I couldn’t inhale.

I was literally in the middle of a sentence saying,

but I tried harder.

I did try marijuana a few times in the ’60s and ’70s. James stopped me mid-sentence, cackled, said,Wonderful, best answer, just the kind of answer a candidate needs to have. You couldn’t inhale—wonderful, wonderful.

So later when I, along with others, was being vetted for the Vice Presidency in 1992, and I had my session with Clinton—a wonderful session in the hotel here—I said,

You know, I’ve already gotten you in trouble once. I think I’m the source of your answer, ‘I couldn’t inhale.’

He said,No, I just said that.

I said,That sounds so much like James when he said, ‘That’s the answer!’ I have my suspicions he put that in your head.

He said,No, I just never could inhale.

So I still blame myself for Clinton. He got attacked very hard on that.

Martin

He did; that’s a great anecdote. Were you involved or knowledgeable when they were considering Lee Iacocca as a candidate?

Wofford

No, I didn’t know they were considering him. I think I knew the one other person he offered it to first. I’m pretty sure I knew that he had offered it—conceivably it came after Iacocca—to Art Rooney, a popular lawyer who has been the head of the family’s Pittsburgh Steelers. He had little kids. Art was just in Nantucket at this year’s Democratic Senate campaign committee’s big donors’ affair. I said,

Art Rooney here is the one I have to thank for the opportunity to be in the Senate, because he turned it down because of his family, and he just wasn’t sure he was right for politics. But he’s only 55 now, so he may still have his chance.

I liked Clinton a lot, just electrically sort of liked him. Intellectually I found him the most stimulating person with a real vision of the world and domestic politics. We just clicked, and he knew we did. By the time he called to ask me to join his campaign, very early, because of my experience on national service with him, my very close friend Paul Tsongas, who was a Peace Corps volunteer in Ethiopia when I was the director in Ethiopia, had announced. This was my introduction of Paul to Emperor Haile Selassie [showing a picture]. I was sort of Paul’s mentor on questions like where he should go to law school or whether he should run for the Lowell City Council and House. I was very close to him.

I really didn’t think Paul with his manner had any chance of winning. I think I was wrong about that. You’re too young to remember—

Martin

No, I was a Tsongas man in ’92. I supported Tsongas in ’92 before he backed out.

Wofford

Well, I went up and did a fundraiser for him, which is in one of your clippings there. I hadn’t forgotten that. It was a big thing. But he knew. When Paul announced, I said,

I’m very tied to Clinton too now. I just don’t think I can simply be for you—but I want to help you.

He said,Will you come and do a fundraiser?

I said,Certainly,

and I did. It was a big one.So when Clinton called, I said the same thing: I’ll try to help, but I can’t join the campaign while Paul is in. I said I didn’t think he was likely to be in very long. The fact is, I think, if Clinton hadn’t—due to Carville’s guidance, I suspect—had a devastatingly negative Florida primary assault on Tsongas, I think Paul could have gone much further and conceivably been the nominee. He was an anti-media type, laconic and underplayed, but interesting. I think I was wrong to think he couldn’t possibly do it. But he didn’t.

The day after he withdrew, Clinton called and said,

All right, now will you join my campaign? I need you now more than I did then.

He just barely got through New Hampshire. He’d done better than people thought he would, but he had Connecticut coming up, and it was looking bad. It was going to be a hard primary. I said,Yes, I’m on call. I’m with you.

So I got the call right away:

Could you be at Newark airport

—or wherever it was—to go to Connecticut?

For probably two days, I was with him—I was more of a living prop than a speaker. But I did speak briefly. Later I did a lot of talks on my own. But on the circuit through Connecticut he had me with him and introduced me, and I said a few things. He used my campaign both on healthcare—whether it was with the Chamber of Commerce or a Democratic rally—and my victory.Because I was there, probably, he used a lot about national service in his talks. Later national service was a major part of his regular performance. He said he got the biggest applause for his national service proposal:

Serve your way through college.

He made it real middle class: help everybody have an opportunity to go to college by seeing that everyone has an opportunity to serve and accumulate, like the GI Bill, enough money to pay for college.On the bus ride across Connecticut, in the dark, Bruce Lindsey came up to me and said,

He’d like you to join you him for the next hour

or something. Sitting with Clinton up at the front of the bus was an extraordinary hour.We got to comparing our marriages, but he mainly wanted to get anything I had to say about what Robert and John Kennedy and Martin Luther King were like. He had all sorts of curious questions about them, good questions, good sharing of his own feelings about the three of them and about the civil rights issue. That’s what we mostly talked about, not national service. We had talked a lot about national service before I had given him my book, Of Kennedys and Kings—it came out in 1980. So somewhere in those early meetings with him, my wife would have been sure I gave him a copy. During the interim after his election in 1992, one after another of the people who went down to Arkansas—like Bill Moyers, when they were talking to him about being Chief of Staff, and other people who were interviewed down in Arkansas—said Of Kennedys and Kings was on his desk in his Arkansas office.

He said he had read the book, but the criticism of Clinton on this score is that he wants people to like him, he wants to win them over, and therefore he knows how to say what they want to hear. I’m sure there’s an element of that in any kind of courtship: he has the energy or the reason, or just the instinct, that comes into play. But I certainly felt that the things he was talking about and saying were very deeply rooted in him and very much his convictions.

So my experience with him on two issues that were crucial to me—national service and civil rights and race relations in this country—and King and [Mohandas] Gandhi—plus his feeling about the Kennedys—from the time I first talked to him about them to this day, tells me that they are deeply rooted, important political ideas. I know very few political leaders who I feel have as deeply rooted a feeling, other than the Christian right—[Samuel] Brownback, for example—that I’m sure his positions try to bring Jesus into the public domain as a guiding force for him.

There’s criticism that he doesn’t have any clear ideas he sticks with. My own estimate is that those were two deeply rooted things he did believe in, does believe in, strongly. In the first year after he was elected, he said about national service,

AmeriCorps is the transcendent idea of my administration.

Now, that isn’t the way his priorities went in terms of his time or other things any more than the Peace Corps was a priority with President Kennedy. In fact, I think Clinton believed in the two points more than Kennedy did—more than he did in civil rights, certainly when he began, and more than he maybe ever did on the Peace Corps.Those are two big things I think he is really deeply rooted in. He undoubtedly has other very strong convictions. So when [Richard] Morris—is that who it is? I couldn’t stand him—came along and was given credit for triangulation and setting him on a centrist course, I’m very skeptical that he came in as a Svengali and moved Clinton to a more centrist position.

If you read Clinton’s three Georgetown speeches again that launched his Presidential campaign and look at his leadership of the Democratic Leadership Council, my sense is throughout his public life that I knew about,

centrist

is too neutral a term, but the vital center, as [Arthur M.] Schlesinger would call it, is where Clinton always was. My instinct is that he went back and re-established touch with Morris because he wanted to get somebody else around him who wanted to go that route, who recognized you had to go that route. He wanted to balance Harold Ickes, or the other gung-ho men of the left.Martin

You talked about this bus ride and Clinton coming up and sitting with you—

Wofford

I went to sit with him.

Martin

Sorry, I got that backwards. What kinds of questions did he ask about the Kennedys? What was he interested in?

Wofford

He was very interested in the contradiction between the high ideals of John Kennedy—and even more of Martin Luther King—and any contradiction in their personal life.

Martin

Was this after the Gennifer Flowers incident?

Wofford

Yes, he had to defend Gennifer Flowers in New Hampshire, I believe it was, when he went on television.

Martin

So it was public knowledge that he had had some—

Wofford

He didn’t mention Gennifer Flowers.

Martin

That’s fascinating.

Wofford

To jump from Gennifer to Monica [Lewinsky], we celebrated Martin Luther King day a few days after her testimony went public, I believe it was, and before his own testimony. Your timeline will show when it was. It was the hot national issue on a day when he had pledged to go to—I think it was Martin Luther King High School, one of the main high schools here, to paint a classroom. Hundreds of AmeriCorps members were organizing students to do service that day. Every Martin Luther King Day, Clinton helped make it a day on instead of a day off. That had been one of the bills I was responsible for, that I initiated in the Senate, with John Lewis in the House, to get Congress to go on record as making it a day for service and to get a little money for mini-grants for service, which went to the Corporation for National Service later.

Anyway, Clinton was to paint this classroom, and the White House asked that I come down and paint with him. He was late getting there, and stayed too long talking to all the dignitaries assembled in the holding room, and then we went upstairs. The rule was the press was going to be let in for only about five minutes for a short photo op to take pictures while we were painting some time during the morning. There would be no questions. The White House was determined that this was going to be Clinton painting with students on Martin Luther King Day, not a chance to ask him questions about Monica Lewinsky. So we were painting in the classroom—or scraping or whatever we were doing—and they let them in, a crowd of them, 30 of them or whatever, in this classroom. We just continued painting as we were told we were supposed to do.

Sam Donaldson shouted out,

Mr. President, did you have sex with Monica Lewinsky?

Clinton just continued painting. I continued painting.I’m afraid you didn’t hear me, Mr. President. Did you have sex with Monica Lewinsky?

My recollection is that he said it three times like that. Clinton never responded. They finally were ushered out. Nobody else did it, but Sam did. This young black student, a very impressive young guy I’d been talking to for half an hour or more as we painted, turned to me and said,Do they really talk like that to the President of the United States?

Martin

That’s a good story.

Chidester

There’s a lot I’d like to cover for the ’92 campaign and even before, your ’91 campaign. But I’m interested in this time, shortly before you’re appointed to fill Senator Heinz’s seat and then in the month after. It’s around this time that the Democratic Leadership Council and the Progressive Policy Institute, the think tank, are writing a lot about national service, and Governor Clinton is chairman around this time, the early ’90s. Did you have any interactions with him in his role at the DLC in constructing ideas on national service?

Wofford

Yes, the panel we had at the Democratic convention in Atlanta in 1988 I think was when he was chairman of the DLC or before it. Each time we talked after the DLC proposal was published that was very much related to what we talked about. I was a strong supporter of the DLC proposal. I don’t know if you know, but Ted Kennedy was a great foe of it, and so was a good part of the black leadership. Some of the college and university presidents, such as Sheldon Hackney—a good friend of mine at the University of Pennsylvania—also opposed it. He was on the evening news saying this is a proposal that’s very unfair to poor black students. White students are not under any compulsion to do service but under this plan, Hackney said, the poor students who need federal aid have this condition for getting aid, engaging in service. That was the crucial part of the DLC proposal.

For me, the hypocrisy of university presidents saying that, when the work-study program of nearly a billion dollars—a little less than that then—in student aid, was conditioned on taking work-study jobs on campus. When we looked into work-study, we discovered that 95% of the work-study jobs were on campus, and in the ’60s when it was started as an adjunct to the poverty program, it was assumed that most of them would be serving in the community as part of the

war on poverty.

New York City under [John] Lindsay, had 10,000 work-study students, according to the chief of the IBM Foundation who was in charge of Lindsay’s youth corps.He says 10,000 work-study students in greater New York were doing their work-study in all kinds of city social programs. College presidents, partly because their students got somewhat radicalized and caused mayors to tremble about homelessness or whatever projects they were working on, and became critical of city politics and city policies. So a lot of mayors didn’t want these work-study students from the colleges engaged in social work in the cities. But mainly the colleges wanted those jobs for their budget. For them to oppose the idea of service-study and the DLC proposal—which was a version of it—to me was very hypocritical.

But Ted Kennedy was very much opposed to the requirement of service in order to get financial aid. After our national service report had come out in 1979, the New York Times had an editorial that I hadn’t read for a long time until yesterday—a friend gave me a pile of documents here. At the end, the editorial on our proposal for national service gives the best case of the people who were opposing the DLC proposal later; since there are only so many dollars that can go to help poor, young minorities, every one of those dollars, every penny of them, should go to help the minorities. Later Kennedy became a big supporter of AmeriCorps, but this as 1979, 1980. I don’t know whether you know, but there was an avalanche of the liberal left attacking the DLC proposal because it would use rare dollars that would go to all students doing national service, and not just to the poor. My own conviction is that serving alongside each other, poor and rich, black and white and Hispanic youth as part of the education of someone who is poor or starts well behind, is probably a more effective way to really change lives than aid programs targeted just on the poor.

One of my turning-point conversations on a service day was again when I was painting on Martin Luther King Day in a Habitat build with the Philadelphia Youth Service Corps. One young man in the Corps they said had been a gang leader, had dropped out of high school in 10th grade, probably was selling drugs, probably heading to jail. He joined the Philadelphia Youth Service Corps, and he’s now a good leader of that

gang.

I said to him,

How did you turn the corner and decide to join this Corps?

He first joshed. He said it was a different kind of gang, might be more interesting, less likely to be killed in the end. We went on painting. Then he finally turned to me and said,I know, there’s a better reason I did it. All my life people were coming to our project to help me—all coming to do good. I got tired of people doing good against me. This is the first time in my life anyone ever asked

me

to do something good.

You know, Marian Wright Edelman, the Children’s Defense Fund Mississippi leader, is so incredibly eloquent against the proposition that if you’re poor and in the ghetto, you’re not able to serve the community and try to change it. It’s not only contrary to her whole religious upbringing in her family, but she educationally thinks that service by young people—and especially those who have been left behind by society—is a key part of the prescription they and we need.

This is a long speech. But Clinton was very heavily criticized by the liberal left for supporting that proposal. I got called by Senator Ted Kennedy to come to his home in Virginia for an evening to figure out what we could do because he supported a domestic Peace Corps, he supported national service, and he didn’t like being in the opposition position. He wanted to come up with some kind of compromise, and he wanted an evening to explore a National Service Act that would have a carrot but no stick. It wouldn’t condition money in service; it would add money. That was the easy answer.

That was the evening we started planning. Shirley Sagawa, who was a very significant person in the Clinton administration, and was number two in the Corporation for National Service when I got there in 1995. Then later she was brought over to the White House to be number two on Hillary’s [Clinton] staff. She was very close to both Hillary and the President. Shirley was Ted Kennedy’s staff person who led the drafting group for the first National Service Act under [George H. W.] Bush, which we did all come together on. But the DLC got really hammered hard. I don’t know if I ever formally joined the DLC, but I was very sympathetic to them, in tune with them on many issues, especially this one. When Clinton proposed it in the campaign, he didn’t propose the condition that was the controversial point of the Democratic Leadership Council proposal. He backed away from that.

But on work-study, he was very strong. In ’93 and ’94 I was pushing very hard on the Senate Labor and Education Committee to move to requiring 50% of work-study over five years to engage in service in the community—it was a plan Ted Kennedy and I agreed upon. He was chairman of the committee. Each year for five years, a 10% requirement of work-study jobs would be added until it reached 50% service-study. We got the 10% through the Senate committee.

Then Congressman [William D.] Ford, the head of the House Education Committee, turned out to be just as much against this as the opponents of the DLC were. He was violently against this. Work-study is to help these kids and not to make them do work in the community. The college and university lobbies campaigned against us. Then in the conference committee, we got through 5%—it has now been increased to 7%. We had Clinton’s strong support for this idea. He came up later with it when we started America’s Promise at the Philadelphia Summit in 1997. It became one of the goals out of the Summit that 50% of work-study should be in service in the community.

Later, when General [Colin] Powell, the chairman of America’s Promise, and I went in to report on the progress—I guess the first year after the Summit, we brought this up to Clinton. He said,

As Harris knows, I think all of work-study ought to be service-study. Why don’t you and I, Colin, send a joint letter to the university presidents asking them to take the lead in doing this?

Colin said,Wonderful, great idea.

We left very enthusiastically. He gave a little speech on why he had been for this for years, and the next thing we knew, the Education Department said,We have the Higher Education Authorization Bill, and the educational lobbies are all against this—

Now the Presidents—like Father [Theodore] Hesburgh of Notre Dame and Tom Ehrlich, who used to be provost at Penn and was formerly president of the University of Indiana and became one of the key board members of the Corporation of National Service—were very much for this. The Washington Monthly had a special major issue in support of this whole approach.

But the Education Department blocked it for basically nine months or a year. Letters were drafted, but we couldn’t get it moving. The next thing they or someone in the White House said, the President of the United States never sends a joint letter with somebody else; that’s against the rules. Then it was agreed there would be two letters. Then word came that Kennedy’s letter couldn’t say 50%; it would call for more service being added to work-study, more jobs in the community, but not any goals set. Then, unknown to me, as the letters were about to go out, the Chief of Staff or somebody from the White House called Powell and said,

We particularly would appreciate your cutting the 50% out of your letter.

So the letters went out to all the presidents.Now, who worked with [David R.] Obey?

Martin

I did.

Wofford

You probably know that Obey had a lot of trouble swallowing AmeriCorps and the Clinton proposal.

Martin

That was before; I worked for him only in 2003, 2004.

Wofford

Okay, well this is 1996 to 2000. I forget when I had my biggest encounter. It must have been the first year, that was when the government had closed down, and one of the things they hadn’t agreed on was national service. Clinton was standing firm on it. They finally caved and gave him money for national service, but they tried to basically cut it through appropriations. I mean through gradually diminishing money, not gradual but big cuts. I went to Obey to try to get him to help us on this. It was actually rather moving. It was sufficiently painful that I didn’t come away feeling any comradely relations with Obey, but I knew where he was coming from. He said,

Harris, you just have to understand.

I don’t know how many years he had been in Congress—20 then, 15.Martin

Since ’68.

Wofford

—since ’68 I’ve been here trying to help those who are most in need in this country, the poorest and the whole range of things that I’ve spilled blood over and sweated over and I believe in. I’m being squeezed and cut by Clinton. They’re cutting down programs that I believe in. You have to understand why I can’t get any enthusiasm for fighting for some new money being given to something that I’m far less convinced is what people need than my programs that I’ve started.

He was very eloquent, very strong. As far as I know he never did—in the hard times anyway. I have no idea where he is now on this issue.

Martin

When I first got there, AmeriCorps was saved for late 2003, early 2004. There was a point where the budget was going to reduce all the money to zero, and then it got put back in, maybe $500 million.

Wofford

Yes. Maybe this year is the first time the House actually put money into AmeriCorps and the corporation in all these years got its money because of the Senate support. An ex-Peace Corps man, Jim Walsh, liked it and supported it, and his dynasty had some good AmeriCorps programs he liked. But each time he said to us—and then he said in a less clear manner to the public:

I’m not going to put any money in for AmeriCorps, because it will be put up against a resolution to transfer the funds to veterans’ health, and nobody wants to vote against veterans’ health. The majority of the people in my caucus don’t like AmeriCorps. If we put money in, it will be voted out on the floor, and it will weaken the position in conference. But I’ll support in conference putting money in

—which he did, every year. But even after Bush called for the increase of AmeriCorps from 50,000 to 75,000, Walsh didn’t think he could put it in. Did you have success on that?Martin

Let’s take a five-minute break.

Martin

Why don’t we start back with the 1991 campaign? I think it would by useful for us to understand better how you came to choose healthcare as one of the top issues; how you and Carville connected, and how the strategy of the campaign started to develop for you in ’91.

Wofford

I don’t know when Carville coined the phrase

It’s the economy, stupid,

which he used in the Clinton Presidential campaign. I can’t remember whether he was using that very line in mine—maybe he was. That was a central idea. The clippings you put together quoting Begala particularly—and maybe Carville, too—about my campaign, saying it was the economic issues. It didn’t take a genius to know that having lost 500,000 manufacturing jobs over the previous 10 years or so, and in parts of Pennsylvania with whole communities down—from coal, most of all, and steel—that the economy was on everyone’s mind.Why healthcare? The economy was a major part of our pitch and our literature and our ads. It wasn’t all healthcare. Many people think the healthcare issue was given undue credit, but I’m not at all sure that’s true either, because it did reach middle-class people and poor people. It reached everybody. The line that was identified with me—

Under the Constitution, if you’re charged with a crime you have a right to a lawyer, so isn’t it even more fundamental that you have a right to a doctor if you’re sick?

—didn’t come from James Carville; it came from the head of the Ophthalmologists of Philadelphia in the very beginning of our campaign. They were giving $5,000 to support me because I was making healthcare an issue.Robert Reinecke, the head, gave me the $5,000 check, their maximum to give. He said,

But far more important than this would be if I give you the copy of the Constitution I carry in my pocket.

He didn’t know that Justice [Hugo] Black of the Supreme Court also made a habit of carrying his Constitution in his pocket. When he was talking to somebody, he’d fiddle in his pocket and say,I can’t find my Constitution; can I borrow yours?

They don’t realize it’s a teaching joke: Justice Black said every American should carry the Constitution in his pocket. Dr. Reinecke said,

Every time I talk in my capacity as head of the ophthalmologists, I say, ‘In this Constitution, if you’re charged with a crime you have a right to a lawyer. Isn’t it even more fundamental that if you’re sick you have a right to a doctor?’ You try it, and I think you’ll find that it helps you more than my $5,000.

So I did. Business audiences, Labor audiences, families—black churches—they’d say,

Amen!

It really clicked. My wife had an autoimmune disease that required a lot of anti-inflammatory medicine over ten years before she got acute leukemia. She was literally scared that if I lost the Senate election I would have no job at that point, and we would lose our health insurance.Now, there’s a six-month provision she didn’t know about until somebody corrected her, that you can continue to pay—COBRA [Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act]. We were doing well. With the nomination, I resigned the state government job. We had no backlog of any money. She said,

How could we afford it?

We were obviously upper middle class. You like to think middle class, but I think in those days it was $60,000 and above and you were in the top 5% of the United States. My wife to this day would never imagine that we weren’t middle class. It doesn’t leave the upper class very many seats.I called Carville and said,

We ought to use this in ads.

He said,Senator, you’re so academic and theoretical. That’s a theoretical proposition. I don’t think that would go in an election, talking about the Constitution.

I said,Well, it seems to be working.

I told him once more that I used it and it got the best response of anything I said. Sure enough, to his credit, when we did the ads, one of them said that. We just filmed it in a studio the first time. Then Carville said,We’re going to do it again; we’re going to do it in a doctor’s office.

My friend Carl Marcy was a medical student then, about to go back to Harvard Medical School, and on this Saturday, he was going around with us as a volunteer in the campaign. The doctor who was going to pose with me in the ad didn’t show up and we were all ready for the shoot. Carville or Bob Shrum, or whoever was doing the filming, said to Carl,

You’re a medical student; put on those robes.

So he got all dressed up in doctor’s white, and he’s in the background of the ad where I say it.Carville got all sorts of kudos for that ad. We encountered Dr. Reinecke on various occasions after I was elected, where we honored him for the election. I did it regularly. He became a living prop. He enjoyed it very much; he’s a real good guy. In the Wall Street Journal, Al Hunt did a column that I read one day before going to swim at the YMCA here. He talked about the genius of James Carville, how he had this academic character for a candidate and he finally got a message down that he, Carville, thought up this thing about the Constitution and that was what really enabled Wofford to carry this message, because Carville thought of the idea of connecting it to the Constitution.

He said,

My nightmare was that Harris would start talking about Mahatma Gandhi, get off message, and I finally found a way to explain to him what ‘Stay on the message’ means. I said, ‘Re-read all of [Abraham] Lincoln’s speeches, from his Cooper Union speech to the Second Inaugural, and you’ll see that he stayed on message. It was how to check slavery without losing the union or how to save the union without expanding slavery. He argued and re-argued it, but he stayed on message.’ That finally got through to him.

Well, I’m the one who said to James Carville one day,

You know, you don’t need to press this point about the message other than to keep reminding me, because I re-read all of Lincoln’s speeches recently from the Cooper Union on, and he’s doing just what you like, James: he stayed right on message.

So I said to Al Hunt,You had a lively column, but each of the stories is sort of upside down.

I told him what I just told you. Al apparently called James right away, and that night I got a call from Carville.Senator, I have an abject apology. I got carried away. I know that that doctor gave you those lines, and I know that you told me to read Lincoln, and I just somehow misspoke.

Martin

For those reading the transcript, we should note that Mr. Wofford is giving a good imitation of Carville.

Wofford

Did my best imitation.

Chidester

Can you talk a little bit more about the relationship between you and those two consultants, Begala and Carville? They’ve become such larger-than-life personalities now, but back then they were—They had run Casey’s campaign, but they weren’t national figures.

Wofford

The Casey campaign should have gotten more attention because he had lost twice before, and lots of people thought the third time was going to be Casey striking out at bat. But he didn’t get that much attention. Casey had an inner sense of grievance. Once he said to me—and I know he said it to a number of other people—

If I had not been an Irish, Roman Catholic, anti-abortion Governor, the kind of victory we had—which was a big victory in the state we’re in—would have made me a contender for the Presidency in everyone’s mind. The liberal bias against someone like me in the Democratic Party is deep.

So, now we get to the morning after my victory. I say that morning, but within 24 hours or so Clinton was on the phone to me saying,

Tell me about this fellow Carville. Should I consider him to be campaign manager for me? What do you say?

I said,

He’s wild and he’s brilliant and he’s tough. It was a good gamble for me, and it would probably be a good gamble for you.

He had a lot of trouble already—no, I guess this is earlier. None of the harder stuff had hit him. He said,I’m going to see him.

So for better or worse, I take a little credit for the events around my campaign. We gave Carville to the public scene. They’re a very good team, especially when they’re together. Paul Begala is as sharp, but has a softer edge. No, that isn’t the right word. He’s more collegial. Carville is dominating, and he expects you to be strong enough to push him back if you don’t like it. Paul Begala is easier going, and so they balance each other; they’re a very good team. It’s easier to like Paul almost all the time. James can get carried away with his conviction about something. He’s learned that to get something clear with the public or even talking to anyone, you have to overstate it and dramatize it as much as you can. Not only the way he talks, which I was imitating, but the thrust of his language.

When you’re riding high with him, it’s exciting. When you’re trying to get another thought in edgewise, it’s a little harder. He’s a very passionate person, passionate about a lot of the ideas he supports with his candidate. I think he’s passionately for social justice. The issue that really concerns me the most is his view of the world. I don’t really know James’s thinking—James’s world view. I have a real sense of his idea of America and what he would like it to be. There’s a critical edge to some of what I am saying about James, but I don’t have that feeling about Paul. They’re both very generous and loyal to people in their domain, on their team.

Martin

From the beginning of this campaign, it seems that the campaign goes beyond Pennsylvania. You’re running against a close associate of George Bush, and in many ways—at least according to these articles—this is somewhat of a trial balloon, a referendum for the 1992 election. Can you go more into the themes you developed, how you went about discussing middle-class issues, economic issues, and what role the national party had in joining you in creating these themes?

Wofford

I don’t remember any role of the national party. Do you know the chairman during that time? I haven’t any idea right now.

Martin

It could have been [Ron] Brown.

Wofford

I don’t think so. This is before Clinton. No, it wouldn’t have been Ron Brown.

Martin

It might have been Paul Kirk.

Wofford

Paul Kirk, very possibly. He was, as a young man, by the way, head of the Young College Democrats, which is the group that actually first put out a proposal for a Peace Corps in the 1960 Presidential campaign. They didn’t use the word

Peace Corps,

I think, but it was the same idea, and something like it had been suggested in several books. The College Democrats—perhaps Paul Kirk—drafted a letter over Kennedy’s signature, proposing this. It went out to College Democrats. None of us knew about this letter until after Kennedy had spontaneously proposed the idea in vague terms at the University of Michigan. In any case, what you most want from the national party, at least according to my Senatorial candidate’s view, is money.Who you want engaged with you is somebody like Carville. You’re plotting the campaign. You just do it directly. But the key unit that we were dealing with was the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee. Chuck Robb was the chair, and this was the year before one-third of the Senators were to be elected every two years. I don’t know how many Senators there were on the Democratic side up for election in 1992, 20 or 15, 19 or whatever. The Senate Campaign Committee was out of money. They were just beginning to try to collect some money for the ’92 campaign. Literally, hardly anyone thought I had a chance. My wife and I did, my sons probably did, and Carville and Begala did. There were some true believers, but not many. I was 47 points behind, I think, in the first poll.

I got extraordinary royal treatment in the Senate after my appointment when I arrived. Half a dozen or more Senators got up and gave little paeans of praise to me. That kind of reception was very flattering. I suppose they were all Democrats, but it’s in the Congressional Record, and I think it made an impression in Pennsylvania that I was treated that way when I arrived.

But Chuck Robb said to the Senators on the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee something like,

I will not approve any money for Harris, however much we may like him, unless every one of the Senators coming up next year agrees that we should go into debt or use the very little we have for him in a probably losing race when there are vital races coming up one year from now.

George Mitchell, Tom Daschle, and Alan Cranston went to every one of those 19 or so Senators—Daschle, I think, was one of them—and talked to them. So in the committee meeting that I wasn’t privy to (it was a closed meeting of those Senators), Daschle began by saying,

I think we have to support Harris with a generous dose.

I think they gave us $500,000, beginning with a quarter of a million and more to come if we showed any gains in the polls. That was combined with Labor’s almost unanimous enthusiastic support—based in part on the conditions of the country, but also my work for four years as Labor and Industry Secretary.The absolutely crucial ability to get on television and otherwise get on the air came from my fellow Senators. Just like that story about the doctor giving the line about the Constitution and healthcare, a lot of the things were on the run, spontaneous as is probably the case in most Presidential campaigns. I certainly know how much more spontaneity and less planning was in the 1960 Kennedy campaign than people think about the Kennedy machine.

But in our campaign, that was certainly true. People who tried to find out how to crack the atom, produce the atomic bomb, had to try different ways to get at it. When we began, nobody knew quite what the way to win was. The press treated me as

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,

a political innocent, an outsider going in. The outsider, the innocent Mr. Smith type, Jimmy Stewart type, was repeatedly in press and other treatments of me. It initially drove my wife crazy. She was a great campaigner, and she thought, You can’t be that dishonest. You’re a fish back in water.When she knew me at 17, I had organized the Student Federalists nationally and had spent a good part of the summer of ’43, my seventeenth summer, in Washington, D.C., lobbying the Senate for the B2H2 bill—the Ball-Burton-Hatch-Hill Bill—two Democrats, two Republicans—to pledge that the United States Senate would support American entry into a world organization with power to keep the peace after the war.

In 1937, at age 11, I was convinced that packing the Supreme Court was a bad thing, and I have a scrapbook with messages from Senators who wrote me,

Master Harris Wofford, thank you for your support of my effort to keep [Franklin D.] Roosevelt from packing the Supreme Court.

In ’36, at age 10, in a Republican family, I had decided I was for Franklin Roosevelt. It was not a Roosevelt-hating family. We always listened to the fireside chats, and I remember listening to his Inaugural Address:We have nothing to fear but fear itself.

I was in politics at age seven. From 1948 on, Clare [Wofford] and I had been at every Democratic convention. In 1944, when I was in the Army Air Corps in World War II, I couldn’t go, but Clare was there. We were always on the floor in some capacity.So she thought this was a complete bamboozle of the public. I was a fish back in water and people should know that I am an experienced political type, etc. James said,

Clare, the best thing we have going is that they think he’s Mr. Smith going to Washington. Don’t you spoil that image.

Then Thornburgh made the great mistake when he left Washington, as Attorney General, to think he was coming back to Pennsylvania for a coronation—that’s the way Republicans treated it. The Cabinet met on the White House lawn and sent him off. I think they had a band, but that may be an exaggeration. They gave him this royal send-off. I think there was a helicopter. But in any case, the press covered this. He landed in Philadelphia, coming back to take the crown.They didn’t actually nominate him until September. This was early summer, I think, or mid-summer. He let them raise money for the pre-primary and during the primary, and then we got into a little trouble because we did the same thing, even though we’d had the convention earlier. But Thornburgh went out in front of the cameras, and almost his opening words—very shortly into his announcement—were something like,

I have walked the corridors of power in Washington, I know the corridors of power in Washington. I can be your representative because I know those corridors of power.

James Carville immediately got me on the phone. He said,

We’ve got him, we’ve got him. You have to go on the air and take him on, right now. In the next ten minutes you have to go out and say, ‘Well, there’s the issue. He wants to go back and walk the corridors of power that he knows so well, and I want to go down and sweep them clean.’

So we hooked him to Washington that first day.On the other hand, after the Gulf War, Bush the First, was what? 70% popular? Carville’s number-one rule, from beginning to end of our campaign, was never criticize President Bush because he’s too popular. You don’t get anywhere doing it. Deal with the Republican administration and the Republicans and their policies and Congress’ policies, particularly in the Senate and Thornburgh’s policies on S&L [savings and loan], but don’t you touch George Bush.

I got carried away about a week before the election in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, I think. It was a labor rally, and I was beginning to feel this incredible surge everywhere I went, an electrical enthusiasm. There were 500—a lot of ex-coal miners and others—cheering. It made me feel like football stars must feel when they win a game in high school.

When I went down the aisle, and one coal miner, I think it was, said to me,

Harris, when you win next Tuesday, it’s going to mark the first day of the end of the Bush administration.

I got up, and the first words I said were,What’s your name?

He gave me his name—Joe Smith, we’ll just say. I said,Joe Smith, right there as we came in said to me and I say to you now that our victory next Tuesday is going to mark the first day of the end of the Bush administration.

They went wild. And the AP [Associated Press] was covering it. It was on the wire within ten minutes:Wofford makes his election a test of the Bush administration.

Within minutes, I had both sons, my wife, James Carville, probably Bob Shrum, all calling to our car saying,

You’ve done it; you’ve blown it; you can’t ever do it; you may have lost the election by saying that when it was just going our way. Don’t ever do anything like that again.

So I didn’t do it again until victory night when I said,As I said last Tuesday in Uniontown, this victory marks the first day of the end of the Bush administration.

By then Carville was happy to claim that we had brought about the first day of the end of the Bush administration.Martin

You mentioned something that struck me as indicative of that campaign: a pioneering of this rapid response to the opposition. It corresponds, I think, to a certain degree, with changes in technology. Email was very new at this point, and fax machines were becoming more and more useful. How did your campaign embrace these technologies? Was that a Carville intention? How did that work?

Wofford

Over my 80 years now, that trend has been so dramatic when you think of it, but I can’t say I was thinking of a technological revolution then. The example of getting on the air right away: as you know, I was in the thick of the Kennedy campaign, and we had a lot of that going on then right away, on radio, less on television. AP was getting its wires out right away.

As for the rapid response, in that sense, Carville—and Begala—were probably far ahead, and I give a lot of credit to Bob Shrum in our campaign. He’s had a lot of defeats, but he ought to get credit for playing a very significant role in our messaging on that campaign. All of them were probably more in tune to the value of the rapid response than I was. It may be that we were more of a sharp example of it than the public knew about before. I suspect Carville’s other earlier campaigns had done it and usually the Republicans have been ahead on things like this—on the negative side, anyway.

But certainly, trying to get on the offensive right away rather than stay on the defensive was our rule, and

corridors of power

was taking the offensive. It was Thornburgh’s offensive, but bang, we were on the offensive once we hit the line,He’s from the corridors of power, and that’s what’s wrong with Washington, too many people like that.

The negative of that was that three years later, we didn’t succeed in the first big debate with [Rick] Santorum. We were each asked to say what our campaign was about. He had the opening gambit. My wife and I had argued with the campaign planning groups, with Carville and Mandy Grunwald, that I ought to be turned loose on national service because I played a major role in getting the national service bill through in 1993—and helped shape the earlier one in 1990 before I was a Senator, the Martin Luther King Day of Service bill. And we had failed on national healthcare. She said,

He’s been championing this for 30 years, and he’s more red-hot on this than anything else. You don’t have anything else that’s a big achievement you can talk about and go all-out for.

James said,

Clare, you just don’t understand. National service is nice, and—unless they’re just against it—most people think it sounds fine. But it’s out on the periphery, and no one can bring it from the periphery into the center of a political campaign. It’s not going to affect anybody’s vote.

He just demolished Clare. She didn’t change her mind, but we didn’t do it. She was particularly arguing for a strong ad on this, an offensive ad.So we go onto the first debate a little later, and Santorum’s lot is to go first. He begins by saying something like,

The issue of this campaign is what has Harris achieved there. He certainly didn’t get what he promised to go down and do, which was universal healthcare, national health insurance. What he did get is AmeriCorps and national service, and that’s a 1960s idea for hippie kids to hold hands around the campfire singing ‘Kumbaya’ at taxpayers’ expense.

I noticed the E.J. Dionne article you gave me quotes Santorum saying,I don’t think I used the word ‘hippie.’

He made an issue of national service, ridiculing it. He was on the offensive. We hadn’t staked our ground and identified with it. He nailed me on it.You might be brighter than I was as to how you answer that and how you get on the offensive again when you face a good strong opening offense. I’ve heard both Carville and Begala say,

We just couldn’t figure out at the time how to go against the strong current.

On that or other issues.We did have a technological breakthrough that almost worked. We were neck and neck the last couple of weeks of October. Teresa Heinz had said that if she thought there was a chance that Santorum could win, she would publicly support me and break with the party, but it was very painful for her to do at that time. But she decided she would. Independently, she got the University of Pittsburgh to call a convocation, invite people from the community and give this speech on what’s wrong with American politics and what’s right with it—her husband, what he stood for, bringing people together in the common good. Not demonizing, not an extremist. Then she ended by saying something like,

That’s why it’s so heartbreaking to find my party nominating a candidate to take John Heinz’s place who represents so much of what is wrong in our politics and is the direct antithesis of John Heinz.

By then it was so late that it was very hard to buy enough time—she didn’t let us put an ad on for another week, until she was sure that we were really in trouble. Then we put the ad on, but we couldn’t get the mass audience we wanted. I don’t know how much effect it would have had, but it was too late. But we had a victory because the campaign had assigned a wonderful young woman who gave us a breakthrough—and the night before the election, when we thought we had turned the corner and we thought the signs were good, we gave her credit for what looked like victory.

She had followed Santorum around with a tape recorder—maybe videotape, I don’t know—and had been taping him. At Temple University she slipped into a class where he was asked,

What’s the problem with Social Security, and what would you do?

He said—more or less, I’m remembering—The problem with Social Security is that people are living too long. When the Act was passed, it was assumed that by 65 most people would be dead. But now they’re living to 70 and 80 and 90 years old. The Social Security system has to reflect the change, so we have to raise the age to 70—and I’d go further if I could—before they could draw on it.

We got that on an ad right away—

I’d go further if I could.

That was about two weeks before the election. We put that out everywhere, and we did pull ahead. So by election weekend, we thought that ad had really saved the day. That weekend there was a surge, all over New Jersey, New York—perhaps a national surge. There was nothing we could attribute it to in Pennsylvania. But if you believed the polls, if they were right before, they said that there was this surge of three, four, five points, and we lost by two points, 80-some thousand out of 3.8 million, something like that. But that was technological. I don’t know how long those tapes have been going, probably back at least to Kennedy’s time.Martin

The ability to turn things around that quickly was probably novel. You book-ended very nicely your two campaigns. So much of your Senate service is tracking parallel to Clinton’s initial run, his victory, the debate on healthcare, and your fate and Clinton’s fate seemed intimately tied together. We were hoping to capture quite a bit of those two stories running parallel.

Wofford

I read a number of the articles you gave me—I think I read them all at the time. It’s making me remember how some astute people in my own ranks, chief of communications David Stone and my older son (or both sons), wanted me to break much more sharply with Hillary’s plan when it was clear that it was going down, to break away much sooner and more clear-cut than I did. They were critical of my loyalty to Bill and Hillary during the Senate period, before the reelection campaign. It was not something I could readily do. I couldn’t do it.

We made one effort to come up with a constructive initiative that might help turn the corner. My wife suggested that we get Pat Moynihan—who had done a lot of damage to Hillary’s plan despite all the good things he did and said in his life—great, good things—by more or less saying that Hillary’s healthcare plan was dead on arrival. The White House in its arrogance—somebody there—dismissed Moynihan in contemptuous form. They said,

What he said doesn’t make any difference,

or something like that. It was very offensive to him.Martin

The quote was that they were

going to roll him.

Wofford

Yes, something like that. Is that what they said?

Martin

Something like that.

Wofford

She thought Pat would probably like to have a constructive opportunity on healthcare, and we got Bob Kerrey, who pegged his Presidential campaign on healthcare, to have a dinner with us. We had a good friend, Tom Hughes, who was an Oxford friend of Pat Moynihan and head of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace then, one of my closest friends of over 50 years, at the dinner too. It was a very merry dinner in Moynihan fashion: Kerrey and Hughes were very witty. And then we got serious on healthcare.

Pat Moynihan said,

Harris, you have to understand that Clinton’s first administration is going to be a catastrophe, but we will teach him how to govern. In his second administration, he may get it right.

Martin

Is this ’92, ’93?

Wofford

This was the winter of ’93-’94.

Martin

That’s very early.

Wofford

Remember that the healthcare plan was introduced by Hillary to the Congress in extraordinary all-day (maybe day-and-a-half) sessions of the Senate and the House. She and Ira Magaziner (and maybe somebody else), presented it and then for hours answered questions. I was sitting in the midst of Republican Senators, who were dazzled by it. They said,

She’s really got it.

The plan was supported by 70% of the people in the first months of polling, and Clinton’s popularity was way up.I don’t know when the

Harry and Louise

ads started, and I don’t know when Arlen Specter started with his Rube Goldberg chart of how complicated this healthcare plan was. For the Democratic answer, we had a far more complicated chart of the present healthcare system. That was on the defensive. But day after day Arlen would go out there with his chart. I have a copy of it, and afterwards I asked him to inscribe one for me. I had it framed. It did huge damage to the plan. It was brilliant, and Arlen just kept going back to the floor with it.And those

Harry and Louise

ads. The state troopers came into the picture, with the story of the woman who complained she went up to the hotel room. The state troopers were giving these remarks, testimony or allegations to the press, and it hit the front pages of papers. Maybe the Paula Jones case was still bubbling along, and Whitewater. By May—six months after the Hillary plan was presented—the Lexis count of newspaper articles showed something like 28,000 articles on sex and Whitewater, or maybe they separated them. One was sex, one was Whitewater, and one was healthcare. Healthcare was down about 17,000. The other two were way up.Clinton’s popularity in the six months had gone from 70% down to 38% or something like that, and the healthcare plan had gone down to 40-some percent. It was kind of the perfect storm of alleged misbehavior by Bill Clinton or the Clintons on Whitewater, which turned out to be nothing, in my opinion—and more her portrait than what I thought that in the end was the opinion of the investigator. It was in that context that the healthcare plan began to look very touch-and-go. We were beginning to be pessimistic about what could emerge—not that we were committed to her plan getting through as it was, but even getting any good, significant leap forward or big first step.

So we had that dinner to consider how to help get that first step. Then Pat Moynihan said,

Harris, this isn’t the time for us to try to come up with a joint plan.

Now, looking back I don’t think he would want to be in a joint plan; he wanted to save the day in a different way or a bigger way than with me and Bob Kerrey. But Pat said,Come spring, there will come a time for a compromise, and you can count on me and we can count on Bob Dole. Bob is a patriot and he wants to make progress on healthcare for everybody. We will come up with a plan, and the sailing will be good.

That was the end of that effort.Come spring, several times I said to Pat,

Don’t you think the time has come?

Finally, rather bleakly, he said,Harris, the time has passed. Bob tells me that they’ve tasted blood in the Republican caucus, and they’re going to drive a stake into this plan. He said he couldn’t get his caucus even to support his healthcare bill if we agreed that the Dole bill should pass.

Our counterpoint, mine and some other Senators’—was to start pressing for a children’s healthcare proposal, to try to get universal coverage for children. They passed the children’s health insurance program [CHIP] in the next Congress. Carville and others think that if that program had been passed that spring, I would probably readily have had those extra votes to win in Pennsylvania in 1994. It would have been a kind of victory, a very significant step.

Martin

You and Tom Daschle had introduced a bill for national healthcare. Was that plan, or that bill, embraced or ignored by Hillary Clinton’s group?

Wofford

Can you date when that plan was? It was before Clinton became President, wasn’t it?

Martin

April of ’92.

Wofford

The Clintons developed their own, somewhat different, approach in the Presidential campaign. They didn’t pick it up as the Daschle-Wofford plan; that wasn’t their business. Their business was what does Clinton want to do? So I don’t think our plan had any impact. I don’t know who was around Clinton on healthcare at that point. I was increasingly focused on our new pitch that we used while I was a Senator and leading up to the 1994 election. What we want is healthcare for all Americans that’s the equivalent of the healthcare that Congress has arranged for itself. This points to an employer-based plan. The government for its employees puts in 75 or 80%, and you then can choose from the whole range of private health insurance. If it’s more expensive, you pay a little more. If it’s less expensive, the government covers a higher proportion of it.

I also had a little victory in the Senate, on the issue of free medical care for Senators. For some reason I had some medical moment that I needed to go to the attending physician, and I learned that the attending physician attends members of Congress and their families and the staff and tourists who are there and get sick in Congress. Senators get free medicine. Admiral whatever his name was, who went up to the multibillion-dollar man—a fascinating admiral, who had been Haile Selassie’s doctor in Ethiopia before we went over there in ’62, a wonderful guy. I had had this good treatment down there. Then I said,

This is wrong. We have this wonderful healthcare plan, and now we also get everything free. Why shouldn’t we pay for this extra service?

It was demagogic in a sense. So I put this bill in, but I made the mistake of not talking to this admiral in charge. It think he’s called the Capitol Attending Physician, but it’s always an admiral.So I went down and said,

I should have talked to you before I put this bill in.

And he said,I understand exactly your principle, Senator, but you have to understand, if yours should pass, I’m going to ask for relief from this job. The reason I like this job is I don’t have to deal with billing. I don’t have to deal with paperwork. I’m not trying to save or to cut costs; I’m just trying to give the best medical treatment. It’s the ideal medical practice, and you’re destroying it for me if it gets passed.

I said,

Would it be that hard to have a little HMO [health maintenance organization]—

which I’d been learning more about—just for these services and get an independent appraisal of what the average value is and charge that? You wouldn’t have any paperwork; somebody else charges the annual fee. Couldn’t we have a very simple one?

He said,

That’s a brilliant idea. I’d love it. That would be fine.

So that’s what we worked out. The bill passed. It was adopted. They estimated, I think, $600 a year, something like that. The House did the same thing soon afterwards. They weren’t very pleased that I had done this, but they figured they had to do the same thing. They had a study as to what the value was, and I think it came out $300 or something like that. It was the same service, but they—Martin

They’re working men over there.

Wofford

They’re working people. So he stayed. But that became my model:

the state employees healthcare plan

—I had that in Pennsylvania in Governor Casey’s cabinet. So this was my own public pitch to people. We did a variety of town meetings and circuits on healthcare. Hillary came to one of the big conferences we arranged. We had a little slogan, a bumper sticker, something likethe same healthcare for you that Congress has for itself.

The Daschle–Wofford plan was a version—not single-payer, but a single-system—that was not employer-based. It was public premiums. I’d forgotten about it until I read the clipping, because it didn’t go anywhere after that.The next thing that happened is Clinton is elected, and then he picks Hillary to run his healthcare task force—which I was intrigued with, and in favor of when he did it. It’s one of those things—she planned a massive set of task forces—that if it had succeeded would be a footnote in history on how you really can get a common problem dealt with by having a lot of outstanding people working on it night and day. I think we had two members of my staff assigned to the Hillary task force, but they were among many other people.

They were off to the races, but under huge pressure. Hillary was always respectful and friendly. If I wanted to volunteer an idea, she was happy, and she was delighted with the staff or persons we had on her taskforce. There were different taskforces where you could have different staff members, and we were very much in the group that was involved.

But I had to fight to get an appointment with the President or Hillary with ideas on the healthcare plan. I’m saying this with an understanding of the pressures she was under from all sides, all the constituencies. She knew I was on her side.

Let me add a parenthesis. The former president of Georgetown before the current president, a priest—unlike the first civilian president they have there now—knew Clinton well at Georgetown, I believe as a student. Clinton’s class met for a reunion while he was President, one of their big reunions. The Georgetown president said to me,

I don’t know anybody, anyone I’ve ever known, who has as many friends who think they’re close personal friends as Bill Clinton. And it goes back to his kindergarten with [Thomas] Mack McLarty, and a second person in Clinton’s first grade or second or kindergarten who’d been with him, in high school. And that was true at Georgetown.

And I know it’s true of his class at Yale Law School.Gregory Craig—you probably will have him for interviews—was Clinton’s private lawyer, brought in to play a major role in the impeachment hearings. He made a big impact on television. Greg for some years was Ted Kennedy’s foreign policy advisor, and he’s a leading partner at Williams and Connolly. He was head of the Harvard student body at the time Clinton was protesting the war in England. Greg was organizing the student body letter to [Lyndon Baines] Johnson against the war—a wonderful guy.

Greg says that most of the people he knew in their law school class considered Bill Clinton the best representative of their generation—although I’m sure there were many people in that class who didn’t. And the same at Oxford. And the same as he went from one place to another.

Jay [John D. IV] Rockefeller came up to me on the floor of the Senate and said,

Harris, I have to tell you—because I know how much you like Bill Clinton, and how close you are to him, and I am, too—I think I love him more than anybody in this Senate. But he never calls me in. I don’t get invited over to the White House. I don’t see him.

I said,I don’t either, Jay.

Jay is a former organizer of the Peace Corps and went to West Virginia with VISTA [Volunteers in Service to America].I said,

You have to realize the other side. So many people he likes feel close to him—think of the pressure he must feel. All these people want to hear from him.

I have two areas of real respect for Clinton in terms of the amazing way he handles the pressures. One is just what the Presidency is like, or what it’s like being a Presidential candidate. Then, once you’re elected, the awe that goes with it—not just of people for the Presidency, but the issues. Of course, from Kennedy on, nuclear war was part of the awe, the power, the burden you have and how much time you have to spend on foreign policy. It’s more than people realize as things blow up here and there, as we know right now.

Then there’s this additional factor of Clinton’s list of close personal

Friends of Bill.

It’s quite unusual to have that on such a scale. In retrospect, I wish I’d had some bull sessions with the President—not just with me, but a few other people beyond Hillary’s taskforce, on healthcare. I have nothing but admiration for my own encounters with Ira Magaziner, but he was in such high gear that I never had any feeling that he thought he needed any advice from me.Martin

That’s one of the criticisms of Clinton’s healthcare program. They didn’t consult the Senate or the House enough; they tried to do a program on their own.

Wofford

I agree.

Martin

Your comment about not getting invited over, and Senator Rockefeller’s concurrence with that, also seems like it’s one of the recurring patterns of Clinton, especially in the early years: not paying enough attention to the Senate.

Wofford