Transcript

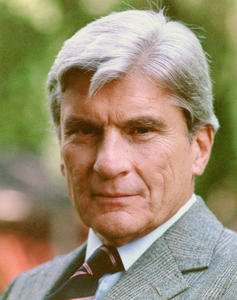

James Sterling Young

What we're trying to do in this project is to get many different perspectives—from friends, from adversaries, from staff—on [Edward] Kennedy. You're one of his old acquaintances and friends.

John W. Warner Jr.

Yes, we go back a ways.

Young

You go way back, so I'd like for you to start out by talking about how you came to know Kennedy. You had known Bobby [Kennedy].

Warner

Let me start this off as follows: The year was 1949. I graduated from Washington and Lee University, which was my father's school. I left there and I went to work as an engineer for a brief time, but then went to the University of Virginia Law School, and his brother was there. You have to picture 1949, that whole post-World War II era—'46, '47, '48, '49. There were colonies of veterans at all your major universities. Of course I lived among them at Washington and Lee. I had had a modest career in the Navy; I did exactly what we were to do at age 17, 18, 19. But it was very much of an atmosphere of veterans, and at the University of Virginia there was a similar situation. There was a village of them; we used to call it Copeley Hill. I don't know if you've ever heard about that. It had little, tiny houses for married ones and so forth.

Anyway, Bobby and Ethel [Skakel Kennedy] bought a house—I scratch my head as to whether I can find it now—and it was a mecca for many reasons, not the least of which was that there was always a refrigerator well stocked with beer, and they played football and things like that. It was through that connection my first year that I first met him. He came down to visit one time. He was somewhat younger, as you know, than Bobby. Then our paths separated; I went off into the Marines and Bobby finished law school. Then I came back and finished my school, thanks to Dean [F. D. G.] Ribble and Hardy Dillard, who really—this time I served in the Marines, over in Korea—put me back together again, not that I was any great heroic wounded veteran; I was just a regular guy who came back. I finished my law school and got a clerkship with a federal circuit judge here in Washington, E. Barrett Prettyman, a wonderful man, and then I went to the U.S. attorney's office.

When I was in the U.S. attorney's office, I got a mysterious call one day from the Attorney General of the United States. Rarely do they ever reach down to talk to an assistant, but anyway, I went to his office. He was a marvelous man. His name was Bill Rogers and he said, "Now look here, John, your name keeps popping up as somebody who we think President [Dwight D.] Eisenhower and Vice President [Richard M.] Nixon are looking for"—this was 1960—"to join us for the campaign of Richard Nixon for President." This all went to my head big-time. I'd been five years prosecuting cases and I was getting ready to move on.

I took the job at the White House, in speechwriting and one thing and another, and eventually became an advance man. That's the individual who precedes the candidate and goes to the villages and towns and cities and states and so forth and sets up the events. Then the candidate comes and he's with you for whatever period of time—maybe it's only a lunch; maybe it's overnight. Then the candidate leaves and you leapfrog and go to another community. I did pretty well at this, and as a result I got some of the major assignments of the campaign that Nixon waged against Jack Kennedy.

To fall back a little, I had married into a family at this time that knew the Kennedys quite well, particularly up at Cape Cod, and I began to meet Jack Kennedy, then a Senator. Later, when he was President, he continued to come to Cape Cod and I was privileged to see him on occasions up there. Ted and I began to get to know each other a little bit with that background.

Amusingly, Bobby Kennedy was his brother's chief advance man, and more than once we met on the field of battle, at political events. He was taking care of the Senator and I was taking care of the Vice President, and we had interesting experiences together, so I saw Ted a little bit in those days. Then our paths parted again because he followed me in law school. I suppose I saw him occasionally, but then we were reunited in 1979, when I came to the Senate and he was there.

Young

Did your paths ever cross when you were Under Secretary or Secretary of the Navy?

Warner

I don't recall that. I just can't pull that out of the ol' bonnet. I testified on Capitol Hill many times. I may have seen him, but we became good friends when we were in the Senate. We both had a love of sailing. He, very nicely, used to invite me to go with him on his sailboat. We sailed a good deal together. Chris Dodd was very much a part of the group that we had. We had some exciting times together, some really exciting sail trips, some of them perilous in a way, bad weather, storms. I remember one time we were on a J-boat, and you can just guess—My golly, a storm came up and started snapping the rigging. Oh, Ted was good.

Young

He was good?

Warner

Oh, he was calm at those moments when the sea was rough. The rougher the sea got, the calmer he got. He was good and he had a love for this. My wife at that time had a beautiful home at Cape Cod, ten to twelve miles from where the Kennedy compound was. We used to go there for dinner occasionally, so I saw him in that framework, but it really was in the Senate, where we were in that cauldron together, that we were philosophical adversaries.

I'm basically a conservative. He's proud that he would be on the liberal side of things. We canceled out numerous votes, but we worked together. He was on the Armed Services Committee and eventually I became chairman of that committee.

Young

I think he went on the Armed Services Committee in 1983.

Warner

Maybe it was.

Young

He started out a hawk on Vietnam and turned against it.

Warner

Well, Vietnam—I was in the Pentagon for five years, in the Department of the Navy; I was Under Secretary and then Secretary. I probably saw him in the context of testifying, but I've always testified before either Armed Services or Foreign Relations, and I don't think he was on—

Young

He wasn't on either one. He moved there in '83—that was when he first appeared as a participant—and you had already been on the Armed Services Committee.

Warner

Yes. I went on the Armed Services Committee right out of the box, in '79. I had the good fortune of having some seniority, for a technical reason, which put me ahead of my class, and I very quickly moved into the position of ranking member, which is in the minority. I served as ranking under mostly Sam Nunn, and then subsequently under Carl Levin, a very dear friend of mine. Of the 30 years I was on that committee, for just slightly over half I was either the ranking member or the chairman. I was the chairman three times, and ranking three times.

Oh, he used to tickle me to death, because the aircraft carriers are made in Virginia; that's the only place they can be made. He would always give this speech, every year, about how [impersonates Kennedy] "John Warner, now the ranking member"—or the chairman—"is going to get another aircraft carrier, billions of dollars, billions of dollars, and what did Massachusetts get? Well, Massachusetts didn't get much more than a Navy band." [laughs]

Another time I encountered him was very interesting. When I was Secretary of the Navy—In those days a service Secretary had a lot of authority. They've since trimmed these guys back to where they're quite different—the Secretary of Defense wanted to reduce the number of bases in the United States, because we were still operating in the Vietnam period, with a base structure that was a holdover from World War II, when we had 16 million in uniform. Now, this was '69. I was there '69 to '74. We had to lower that structure, so I made the decision we'd close the Boston Naval Shipyard. Well, that's the home of the USS Constitution, [laughs] which had fought the Barbary pirates, and there was all the other history and everything else connected with that shipyard. It produced one hell of a row in Congress. I also proposed closing the Newport destroyer base, up in Rhode Island.

We had a hearing in the Caucus Room. The Chief of Naval Operations and I were put in the dock up there for two days running, while Kennedy and [John] Pastore and all of the New England Senators just ripped us to pieces about how we had no sense of history, that these ports had served the original colonies. "What in the world are you guys thinking about?" Well, I was thinking about (A) saving money, and that (B) it was so cold up there that operating schedules were difficult in the winter, when I had ports in Florida open 365 days a year. Ted came up there, he and Pastore, who was a very colorful Senator. He was a short fellow and he had a high-pitched voice, but man, could that tongue lash. I have pictures up there with Ted and all that.

We went through that episode together when I was Secretary of the Navy, so I'm glad you brought that up. It carried over with him, "How many millions is that carrier? One, two? Let me—" He would pick up the sheets. "Oh no, this one is $1 million more expensive than the other millions, and I got a Navy band." Oh yes, he did a little work on the dock up there. But all in good spirit.

He was chairman of the Seapower Subcommittee and I was the ranking member, so we rocked back and forth through those years. I added it up the other day. I served with 262 Senators in my 30 years, and I'd have to tell you, as I look back—I love the phrase the "Big Ten" in football—he'd be one of the "Big Ten" that I've known, not only because of my really deep respect for him, almost very loving affection for him as a human being, but as a Senator himself. He's a titan.

Young

He grew into that, didn't he?

Warner

I did too. I came having had no real experience in politics, only as Secretary of the Navy, and everybody thought I bordered on idiocy. The old political structure of my state said, "Boy, you have to start in Congress," or "You have to go to the General Assembly"—as they say in Virginia, you have to "come up through the chairs." Well, I tend to be somewhat of an impetuous character and I don't take no for an answer. I assaulted the walls and barely got through, by four-tenths of one percent in my first election, but then I worked very diligently, as you pointed out about my colleague Ted Kennedy, and slowly threw off some mantles that I had. All of us come to these jobs with a certain amount of scar tissue.

Young

And you develop some when you get there.

Warner

You develop some along the way. I then ended up with a pretty good career.

Young

I'm interested in how Ted moved, during the [Ronald] Reagan years, into arms control—or he started that even earlier—and from arms control into the Armed Services Committee, which was a new interest for him, because most of his thrust had been in civil rights, domestic issues, labor issues.

Warner

He was in the Army for a while—

Young

Yes, 1952.

Warner

And he adored his brothers. Of course the two older ones had distinguished naval careers. I can't quickly put together Bobby's, but Bobby at some point belonged to the military.

Young

I don't think he was in combat, but he was in the Navy, an officer. Jack, of course, was.

Warner

Jack was an officer; he was in PT [patrol torpedo] boats. And the brother [Joseph P. Kennedy Jr.] was a naval aviator.

Young

That's right, and Ted became an enlisted man.

Warner

Yes. Well, that's all right, so was I. I was an enlisted man, and then got my commission.

It took me almost two years of campaigning in my state to get into a posture where I went into what was basically a convention, although it was a primary—It was a mixture of convention and primary—and I lost it. There were four of us in it—Linwood Holton was one of them—Linwood, Dick Obenshain, Nathan Miller, and myself. For a good 14 months we traveled the state, the four of us, debating in the old-fashioned way, on the soapboxes. We didn't hurl a lot of negatives at each other. We didn't have enough money to buy TV; TV hadn't gotten into politics back that far. It was good old-fashioned politics.

It went into a convention with 10,000 people. It was a Guinness world record. It was the largest number of voting delegates ever assembled for a political event in the history of the country, and I lost on the last ballot. I came from fourth to second; Holton dropped out and pitched much of his strength to me, a footnote of history. Then the fellow who won the nomination—it's so tragic—was killed campaigning, in an airplane crash. I then had ten weeks to put together a campaign, and here I am.

We all come to this office—not only we, the candidates, but also our families and our friends, who unite and sacrifice tremendously to enable us to get here—and the one thing that bonds us all is that we feel that everybody's gone through pretty much the same struggle. There's an underlying friendship among us.

Young

Especially among the people who weren't the "old bulls" in the Senate. They were going out, weren't they, when you came?

Warner

They were going out. I probably represent the last of it. I was fortunate to have the seniority to move into a leadership position of the Armed Services Committee very quickly. I think I was the first chairman among my classmates.

But the old bulls were wonderful human beings. Each one was different, but I remember John Stennis was the chairman of the Armed Services Committee when Ted joined, about '83. Oh, what a magnificent—He came from Mississippi, the old school, very straightforward, honest, soft-spoken. He had lovely stories he would share with me. He took a particular fondness toward me. He told me one time, "Now look here, Senator, there will be many times in which you are called on to speak and you've had no opportunity to prepare, you know very little about the audience, but above all do not have a moment's apprehension. Stride into that room, grab the rostrum, and look at them for a minute. They'll look at you, because there are only 100 of us who represent 300 million people. Then start talking, and eventually you will think of something to say." Those were the teachings.

We had a system, when I came, of big brothers, or sisters if the case may be. We only had one woman in the Senate and she came in with me, Nancy Kassebaum. But Johnny Heinz of Pennsylvania—a wonderful friend and a good friend of Ted's, lost in an air accident—was my big brother. He helped me develop and took me under his wing, and Stennis took me under his wing. Ted would be the first to tell you [Henry] Scoop Jackson took us under his wing. They were giants, and old Barry Goldwater, my God! Ted loved Barry and Barry loved Ted. Those two guys would get into a verbal wrestling match on the floor; it was fierce the way they went at it together.

Young

People don't understand that well, do they?

Warner

No.

Young

I'm hoping that one of the things we could get out of this oral history is a picture of what is so invisible to most people who watch and listen. It's always people fighting. They can't understand how two guys—

Warner

It's different today, and I would recommend you find another Senator, one who is right there in your backyard, Lowell Weicker [Jr.]. Lowell Weicker is living in Charlottesville now. Give him my warmest regards when you see him. Search him out because he and Ted would go at it ferociously. He'll give you a perspective on Ted that's worthwhile. Lowell is an extremely bright man. He was defeated because he was so liberal, and then he became Governor of Connecticut. He's a marvelous man, but he'll give you a perspective on Ted Kennedy. He never got to be an old bull, because he had a fairly short career, but the old bulls really took you under their wings.

Young

There's Jim Eastland.

Warner

Oh, Jim Eastland, I remember him well.

Young

I love these stories because they tell a lot, and Ted has stories about Jim Eastland.

Warner

Jim would see you at 5:00; that's when he wanted to see other Senators. When you came, there was a drink waiting for you. If you didn't drink it, there wasn't going to be any meeting. Of course he had, in his pocket, all the federal judges; he was chairman of the Judiciary. Many a time I went in there and limped out on one leg, but I got my judge. [laughs]

There's another thing about the Senate that's changed. In that environment, the Senators had their families with them. It was very much of a family affair, and I'd be less—Ted would agree with this—The wives were a marvelous bridge after hours, to reunite the warriors bleeding from the collisions on the floor earlier that day.

Why is it gone? Because of the enormity of the amount of money a Senator must raise now to get reelected, or to help his colleagues get reelected. The focus of the Senate has drifted into these enormous, expensive campaigns, all across the state. For example, my first campaign, which was somewhat of an abnormality because I only had ten weeks, cost me less than $1 million. For the last big campaign in Virginia, which was in '06, both candidates were in excess of $25 million. Now, to raise $25 million in the small increments under the laws is a lot of work, a lot of expenditure. A Senator often feels, I have to go home every weekend. Should I bring my wife and children here, knowing that they'll be here by themselves on the weekends? These families have to go through these difficult family decisions.

In those days, when I first came to the Senate, 85 to close to 90 percent of the Senators had their families here. Today, I think it's 50 percent or less, and that has contributed, unfortunately, to what is perceived as, and in some respects is true, the erosion of bipartisanship. If I may say with a degree of immodesty, one of my hallmarks is I always was very bipartisan. First, I thought national security was a bipartisan subject. It shouldn't be invaded by partisan political considerations. We have to do what's best for the nation, irrespective of the political fallout, and I always had that strongly as a chairman. Now I'm straying a little bit from your subject—

Young

No, no, this is all very good. Did Ted have that same feeling? He has such a reputation as a—

Warner

The warmth of his personality was much respected and enjoyed across the aisle. He was bipartisan because of the strength of his personality and the warmth of that personality, and the joie de vivre that he had. Was he a person who sat in the back room trying to figure out every piece of legislation? I'd have to reflect on that because a lot of his work was in health. He was on the Judiciary Committee for a while. He was actually the chairman for a while, but his first love was education and health. I was on the committee for a while—Education and Health—but you'll have to ask somebody else on that. It was the strength of his personality that attracted men and women to him from the other side of the aisle.

Young

On his initiatives, he usually had allies across the aisle.

Warner

Oh, yes. Oh, yes.

Young

When I first talked with him about doing this project, he said, "Now, Jim, I've worked through a lot of alliances, and I want you to be sure to cover that in your history, and talk to some of them. You know, of course, Orrin Hatch and the others, but it goes beyond that." Did he ever make an ally of you on a particular issue?

Warner

Oh, yes, a number of times. We worked on arms control. He was a little more liberal than I was. I just brought this out; it's a picture of me when I was Secretary of the Navy. I did a special executive agreement with the Soviet Union; it took me two years to negotiate it. I'd come back to Congress and report to the Congress on what I was doing, because they were all suspicious that we were selling out to the Soviets. I met him in the context of that work. You mentioned his interest in arms control.

Young

Right. I was particularly struck by that, and he talked to me about it, but I haven't heard about it from anybody else. I'd like to hear about it from you, if you recall. This was on the Senate Observers Group.

Warner

Yes, we were partners together.

Young

You went to Geneva. Max Kampelman.

Warner

Oh, Max was the Ambassador, a wonderful man. Are you going to talk to him?

Young

Should I?

Warner

Oh, yes. He has a bit of age on him, but the last time I saw him, which was within a year, he seemed to be quite lucid. He can give you more about that. That was the Senate Observers Group, an ad hoc thing.

Young

Did it amount to much?

Warner

Yes, it really did. We had the ones like myself, from the conservative perspective, and Ted, from the more liberal perspective. It gave us a chance to travel. Senate travel is really quite a valuable thing. It's disparaged a lot. It's true that on trips you'll go a watering hole, Paris or Madrid or something, but ordinarily you're doing a lot of work out there. My last eight years in the Senate were going back and forth to Iraq and Afghanistan constantly, and I lost out on many trips to other areas of the world. No, Ted was right about that Observers Group.

Young

That was a bipartisan commission.

Warner

Yes, and it was an ad hoc thing that was put together. The other is the Gang of Fourteen. He was not on that, but that's where we got some judgeships. He was not a member of it, but it was another example of where we had nontraditional groupings of Senators together working.

Young

When it came to the [Robert] Bork nomination, where he came out right away, the minute the nomination was announced—For some people on the outside—I don't know about on the inside—that fixed Ted Kennedy as somebody who polarized, as an attack dog, and as a real left-winger.

Warner

That was because Bork was pretty much on the opposite side of the spectrum from his philosophical base.

Young

That's right. You eventually voted against.

Warner

I was one of 15 Republicans.

Young

Yes. How do you see Ted's performance on the Bork nomination, and what do you think people should—

Warner

It was a very substantive debate over quite a period of time. I say substantive because many Senators participated. Almost every member of the Senate got into a debate scenario. This business of going to the floor and reading a speech is not a debate to me. There's less and less of it today than there was my first 20 years in the Senate where, without benefit of but maybe a few notes, you just go at it on the floor, without benefit of a lot of written text. That was very prevalent during that Bork debate, and he was the leader. He dug in; there was no doubt about that. When you think of 14, 15 Senators from the Republicans going over, that's a large number against their own party's nominee, so there had to be a good deal of persuasiveness in that debate, coming from the leadership of the likes of Ted Kennedy.

Young

He's known to do a lot of homework and a lot of preparation.

Warner

Few people realize that, but this man is a prodigious, prodigious individual when it comes to preparation and homework. I've been with him on airplanes where he was writing and rewriting and scratching stuff out. On the floor of the Senate, if he ever found that one of his speeches wasn't perfect—boy, he's worked everything over.

Young

His staff really—

Warner

But he's always attracted a first-class staff. That was one of the benefits of a very extraordinary family, and an extraordinary chapter of American history, from father on down, and there were many people attracted. I remember the '60 campaign, the excitement and the fervor engendered by this Senator who came up and tackled the Vice President of the United States. It was very interesting, a great political campaign.

It's not only homework, but he is a hard worker. He tries to do as much as he can with his friends—not based on friendship, but he respects the other Senators and he'll do little things for them. He has a big heart.

Young

He has the personal touch.

Warner

Yes. His heart is as big as his derriere, and that has some magnitude to it. [laughs]

Young

Especially in recent years, yes.

Warner

No, back when I knew him.

Young

He was already getting—growing out.

Warner

But that's a big heart. Maybe it's a bad metaphor, but anyway.

Young

He said to me once that in school he had to work twice as hard—

Warner

Yes, well, I did too.

Young

Because everybody else seemed to get it.

Warner

I don't think either of us prided ourselves on great intellectual genius. I certainly don't pride myself. I had to scrap my way along.

Young: Didn't he lend you his father's cane once?

Warner

Yes!

Young

How did that come about?

Warner

I can't remember. I had an operation about three years ago and an infection set in to my groin. One leg was in pretty bad shape for around six months, and that could have been one incident. Then, I came off of a horse one time; I used to ride a lot of horses. There were two periods in the Senate where I had to use a cane. And he did; it was very thoughtful of him. I remember that. I remember walking around showing everybody this cane. It came down through generations. You've been in his office, haven't you?

Young

Oh, yes.

Warner

You've seen the Time magazine, that silent message as you come in and you just look at that historical Time cover.

Young

And it's the cane he's using now.

Warner

Isn't that interesting?

Young

His grandfather's, then his father's, cane, from when his father got sick.

Warner

You know Claiborne Pell, another one of those northeastern rascals. He wore his father's belt, but the trouble was, his father was probably 42 or 43 inches around and Claiborne maybe had a 32. As a result, he'd have this thing that dangled down there all the time. We used to—You ask Ted about Claiborne Pell. He wore some of his father's things. [laughs] Oh God, funny! Funny, funny, funny.

Young

The Senate had characters.

Warner

It really had characters, but they were marvelous characters. I miss it dearly, but the Senate I fell in love with, and fortunately was a part of, is no longer there. Things move on in life. These men are driven now to go home every weekend or out across America to raise this money. It has eroded those types of relationships.

Young

I'm quite struck by the fact that Kennedy managed—of course, he didn't have the fundraising problems, I guess, that others who had competitive seats did. He's survived the change and it hasn't—He can run circles around me.

Warner

No kidding, up until this recent—He was so energetic. I knew his previous wife, but the current wife is a pillar of strength.

Young

Vicki [Reggie Kennedy].

Warner

She really is. I've been privileged to be with them socially on a number of occasions. She's doesn't trade at all on the Kennedy name; she's her own individual and a tower of strength for him.

Another hallmark is that he writes the most beautiful letters to his colleagues. We were both knighted recently—I don't know whether you know about that little chapter—and he wrote me a beautiful letter, and I think I wrote him back a nice letter. Then I had a little bout with the old pump here [touches chest] six months or a year or so ago, and he wrote me the sweetest letter and calls all the time. He's very dutiful about a colleague when a colleague has those brief interludes of loss of family or health or whatever. He's one of the first to come.

Young

That's another thing I hear a lot about, how he cares for others.

Warner

Oh, yes.

Young

And it's not just colleagues.

Warner

No.

Young

It seems to be a general character of his, like with the [Brian] Hart family and other people in Massachusetts. He really does put a lot into that.

Warner

No question. He has a wealth of friends. I'm privileged—I was invited to work on this library that we're trying to put up for him. The outpouring of people who have come in to work on that. It's the building that's going next to his brother's library, and it's going to have a replica of the Senate floor.

Young

It's going to be the [Edward M. Kennedy] Institute for the United States Senate.

Warner

There's only one problem with that. I don't know whether I'll have a chance to share it, because I'm now embargoed against having any relationship with my former colleagues. It's the roughest law. If you meet them a little bit socially, they'll—

Anyway, he's going to re-create that Senate chamber and bring in, say for a weekend, a group of youngsters to debate. Nobody has calculated: If you have 100 youngsters, 100 "Senators," the amount of time each is going to have to debate is not exactly going to work out for a weekend. Somebody has to run that calculus, because the great debates in the Senate usually take place when there are about two or a maximum of three on each side, going at it on the floor. They'll go at it for an hour or two and others will come in and watch, maybe seek recognition and ask a question.

Young

They'll have to get the numbers down.

Warner

I haven't figured it out. It's a great idea to re-create the Senate chamber, and to make it available for the kids, but assuming the kids are only there for 48 hours, to get 100 of them to debate, you're going to run the clock out.

Young

I think it's a good idea—

Warner

Oh, I do too.

Young

But how do you pull it off? He's pushed harder to get that done now that he's gotten sick.

Warner

Well, I hope he's coming out of this. When did you last see him?

Young

About ten months ago.

Warner

Ten months ago?

Young

In fact, I've had an interview scheduled. I've had 23 sessions with him, two or three hours each.

Warner

You are going into this beautifully.

Young

He is very dedicated to this project.

Warner

Oh, yes, he wants it.

Young

He wanted to be the first one to be interviewed—

Warner

Of course.

Young

So as soon as the project was announced, I'd go up either to his house here or to the Cape.

Warner

Oh, yes. He loves the Cape.

Young

I don't get seasick, fortunately.

Warner

The last time I went up and saw him at the Cape was about two years ago. My wife and I, and my son and my son's wife, were invited to go sailing with him. First we came out of the dock and he suddenly decided he was going to race a member of the Kennedy family; I've forgotten who it was, but we almost had a collision at sea, racing those ships. He was bracing the ship over, into the wind. We got by that and then we started a nice sail toward Martha's Vineyard or Nantucket, wherever we were headed. Off to the right came a ferry and Ted said, "We're going to be all right; we'll get through." Between his course, wild winds, and one thing and another, the next thing we knew the ferry was blowing the whistle wildly, and Ted was just merrily sailing along, with the ferry in reverse, and he said, "Sailing vessels should have the right of way to these ferries." My wife and I were—but he was calm. We just sailed by and the ferry went right on behind us. Oh, he's good.

Young

Is he reckless?

Warner

No, no, no.

Young

He knew what he was doing?

Warner

He knew what he was doing. He knew the speed of his ship and he could calculate, even though the fellow was blowing the whistle, one thing and another. He's not reckless, at least not when I was with him.

Oh, this is a wonderful interview. It brings back such happy memories for me. What else can I add? I haven't covered very much.

Young

Do you want to talk a little about playing tennis with him?

Warner

Oh, God! [laughs] He is funny on that tennis court. He is a fierce competitor and hits the ball—If he hits it right, it's like a cannonball coming across. We liked doubles with girls; it's a lot of fun to play with the ladies. I played many nights with him. Oh, my gracious, I remember one time we were up sailing off the Connecticut shoreline. We went to visit his sister, who has a house up there.

Young

Jean [Kennedy Smith]?

Warner

Yes.

Young

Jean moved to Long Island. Eunice [Kennedy Shriver] has a place up there.

Warner

Well, one of them. We overnighted and played tennis; it was so dark we couldn't find the balls, and he didn't want to give up, even at that. I think if he'd had a way to get out and play with a flashlight, he would have done it. We had such a wonderful time.

That was the time we got into a storm, just Ted, myself, and Chris Dodd. We got into a pretty fierce storm and he very wisely said, "We're going to berth this thing at the first dock we see." We spied this dock and pulled in, berthing the sailboat, and we suddenly realized it was Benno Schmidt's; he was the president of Yale. Ted said, "Oh, that's fine. Benno, he'll take good care of us." We went up, and the house was all locked up. By this time, we'd run out of adequate fuel for ourselves—You know what I mean?—so we had to skillfully figure out how to get into Benno's house and get into his liquor cabinet, [laughs] which we managed to do. I remember Ted saying, "Now, don't you guys talk about this. I'll call Benno up myself and explain what happened: we had a bad storm and we were all cold and wet and everything." But I was thinking, Oh, yes, yes. I met Benno later and he said, "Yes, I hear you guys broke into my house." [laughs] Of all the houses to break into, it was the president of Yale's house. I could tell you all kinds of stories like that.

Young

In the '80s, after he broke up with Joan [Bennett Kennedy], he still had the house in McLean. This was before Vicki.

Warner

Oh, God! Oh, the birthday parties!

Young

The birthday parties, talk about that.

Warner

They were the best parties, I tell you. We all had to come in costumes, and the girls would have to wear tutus, very respectfully dressed, but the little tutu skirts, or I guess they could have worn another thing. Oh, do I remember those parties! They were great. They never got out of hand, but everybody was so into the party. We had the grandest times together.

I'll never forget one of the parties. I'm full of mischief and Chris Dodd was there, and Chris was—I think he was courting his current wife—trying to be on his best behavior. Some other guy and I concocted that we'd bring a crate of live chickens, [laughs] and turn them out in the middle of the party, to cause a little confusion. Well, somebody spied the crate of chickens before we had a chance to release them. This was 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning, at the tail end of the party. OK, so we weren't going to release them; what were we going to do with the chickens now? Well, this other fellow had more mischief in him than did I. He said, "We're going to teach Dodd a lesson. We're going to let the chickens out in his car." We found Dodd's car and put about six live chickens in it, and they spent the bulk of the party in Dodd's—Dodd came out in the morning to get in his car. [laughs] It was a mess. That's the sort of high jinks we used to have around there.

I remember another guy—I won't give you his name, he's a Senator—because he kind of got into it. It was a costume party. Ted used to frequently come in as a Roman emperor, in his costume, but this guy came dressed as Fidel Castro. He had the whole thing, and it was a really remarkable likeness. Well, the word got out that it was Fidel Castro at Ted's party. [laughs] Oh, do I remember those parties up in that old house in McLean. I was dating, at that time I think, one of Ted's former girlfriends, a lovely lady. I took her once or twice to those parties and everything went just fine.

Young

Was there a lot of singing?

Warner

Oh, yes.

Young

Ted loves to sing.

Warner

There was a lot of singing. We had good band music, but then we'd sing to the bands. Nothing got out of hand, just funny things happened, but beautiful costumes. Everybody really tried to lay it on. I went dressed as an admiral or something my last time. I had been Secretary of the Navy and I thought, I have this old costume and I never was an admiral, never will be, but I'll put it on for the party. Oh, you brought a laugh out of me with that one. What else do you have in your pocket?

Young

The tennis at the house in McLean in the '80s; you and Lee Fentress were often there.

Warner

John Culver was a funny guy. I don't know if you can get to him or not.

Young

Yes, I have. I've interviewed him.

Warner

He's wonderful. He's a man who retired before his time. He was a giant in his mind and his voice. He and Ted were great pals. I could go on and on. They used to have probably a dozen or more Senators at that party, of both parties, Republicans and Democrats. Old John Culver, he was the best. Vince Wolfington—have you talked to Vince?

Young

No. I'm going to.

Warner

He's funny; he's good. What else do you have there?

Young

I guess you didn't really know Jack or Bobby all that well.

Warner

No. I had met them and was with them probably a dozen times.

Young

What do you see in Ted that's like or not like what you saw of the two brothers? How is he different from them?

Warner

All of them had a measure—I guess they were driven individuals. They felt they had an obligation to repay society and the country, and a strong strain of patriotism. Unfortunately, that word has begun to have a different context from when I grew up with patriotism. His brothers were extraordinary, the two older ones; they were naval heroes, with a very great love of country, driven. I never knew the old man, but I think he instilled in these guys an obligation to succeed in whatever they turned their hand to do. That's what I was told.

I knew Jackie [Kennedy Onassis] quite well. I'd been raised with Jackie. Not raised in the sense of—I was a part of the little social group in which we grew up. As a matter of fact, I had a farm in Virginia and the home that Jackie bought down there for them was right on the butt end of my farm; I knew the house well and visited them. She and Jack were only in it two or three weekends before he lost his life. She stayed for a while and then let the house go, for obvious reasons. I knew President Kennedy through his wife. I was invited to several of their White House dinners when he was President. My oldest daughter went to playschool at the White House with Caroline Kennedy. The President and Mrs. Kennedy set up a little kindergarten-type thing there. I used to drive over—How easy it was to drive right up through the way—and drop off my daughter and pick her up. It was a simple life in those days.

What else? I came to know Ethel fairly well. She was a tower of strength. Eunice and [Robert Sargent] Sarge Shriver—I've been privileged to know them and call them friends for years.

Young

Ted's father is said to have said that he was the best politician of the boys.

Warner

Is that right?

Young

Yes.

Warner

I never knew that. Certainly Bobby didn't have that outgoing, bon vivant—Ted had a bit of the Irish in him, you know. That big arm would go around your shoulders and crack your ribs if you weren't watching out. Now the Senator, later President, I watched him on the campaign stump. I'll never forget, and I don't know whether this is germane or not, but there's an annual dinner given in New York called the [Alfred E.] Al Smith Dinner.

Young

Oh, yes.

Warner

I was the Vice President's advance man to the Al Smith dinner, and Bobby was the advance man for his brother. In preparation, I went to see the Monsignor and I said, "Monsignor"—I did it in a very respectful way—"is there an alternative to white tie? A black tie?" He looked me and said, "Absolutely not, young man! You have not prepared for this briefing. It's always been white tie! Do you understand that?" "Yes, Your Grace, I understand that." I carefully made certain that the Vice President, in his gear kit, had his white tie and everything.

I was up in the room with Nixon as he was putting on the white tie and fussing, and he said, "You know, I don't like white ties at all. It just reflects too much the wealthy part of society. Are you sure I have to wear it?" I said yes.

Fast-forward. I was in my white tie and went down to the holding room. Big Jim Farley—Do you remember him? He used to be Postmaster General—was running everything, a commanding figure of a man, and everybody was in white tie. I spied Bobby coming down the hall, and he was in a black tie. I said, "Hey, wait a minute. Didn't you get the word?" He didn't say anything to me. Then down came the Senator in black tie. I was saying to myself, Uh-oh, I'm in for it. I guess protocol was that Nixon came after the Senator had arrived. He walked in that room, saw them, pulled me aside, and said, "You done me in." I said, "No, Mr. Vice President, I followed instructions." "You done me in." The next morning the tabloids pictured them both, "Black Tie Versus White Tie," "Poor Man's Tie Versus the Rich Man's Tie." Oh, God, Nixon chewed my ass out.

I'll never forget another thing about that—where Bobby was I don't know, but I did the planning to take Nixon to California the day of the election, so he could vote and be in his state watching returns. I remember sitting in that hotel suite until about 2:00, 3:00, 4:00 in the morning, and the thing was indecisive; the winner wasn't clearly pronounced.

The next morning the Vice President said, "I want to pack up and go to Washington." I said, "Fine, I'll do it." I made my usual call to American Airlines, or whatever I was dealing with, to order a plane, and they said, "Sorry, but the credit is no longer in place, it looks like the election is lost." They weren't going to give me a whole damn plane because it cost—I don't know what it was. I called back to some friends and raised the money quickly to get the plane, got the check over to American Airlines, and got the plane. Then I spotted the plane at the L.A. [Los Angeles] Airport. It was way out on the end, so the press were really searching for it. The Secret Service got him out of the hotel, got all his staff on the plane and everything else, got him in a car, and drove out along the runway to get him out to the plane. We arrived at planeside—this is an interesting point of history—and it was kind of muddy, puddles of oil and all kinds of stuff out there.

A mechanic was out there who was assigned to make sure that everything was OK on the plane before it took off, and he was listening to a little hand radio. The Vice President was walking toward the plane and heard the radio, so he went over to the man. The radio was talking about the returns, and the votes in Chicago; you know, 4,000 or 5,000 votes were in dispute, and it could have swung the election. Here it was, in L.A. time, about 10:00 in the morning, which meant midday back here or thereabouts. Here was this very nice grease monkey and Nixon, the Vice President of the United States, both holding a hand radio, listening to the returns.

Nixon had with him his press secretary, a guy named Herb Klein, and another individual whom I can't remember, and they listened to this. Nixon turned to Klein and the other guy, and to me, and said, "Get Eisenhower on the phone." "Yes, sir." We got Eisenhower on the phone and he said, "Mr. President, I don't think it's right for the United States that the succession of the Presidency should ever be in doubt for a minute. I'm not going to contest this election." I didn't hear the other part of the conversation, but I later learned that Eisenhower said—I don't know what he called him, "Mr. Vice President" or "Dick" or whatever; they had sort of a strained relationship—"I agree with you. You do the right thing." At that moment, right there, he instructed his team to say that he was going to concede the election to the Senator. That's a moment in history I'll never forget. We got on the plane and brought him back to Washington.

Young

How were the relations between Nixon and Ted?

Warner

I don't know. I can't answer that.

Young

Was Bryce Harlow—?

Warner

Bryce was very much a part of many of those things. He was more in the White House. I was in the White House for a brief period, training to take on this thing. I was in speechwriting. It was interesting; a Cabinet officer would go give a speech, and my job was to read the speech and get at least one, and hopefully two, quotes of Nixon, and splice them into the speech. This wasn't an intellectual challenge, but at least I was doing that. Bryce was a great tower of strength to all of us. I got to know him slightly. I knew him in later years.

Well, I've bent your ear enough. I don't know what you're going to do with this. You don't have much in there to deal with, maybe one or two quotes.

Young

Well, it's the quality, not the quantity, that counts.

Warner

Maybe, who knows? But I've enjoyed it. I've enjoyed meeting you. Give my good friend, the Governor [Gerald L. Baliles], my warmest regards.

Young

I'll do that.

Warner

Tell him that, from all appearances, you think I'm in fine fettle, sitting up here in this great big law firm with 1,200 lawyers in it. I was in this firm when I left to become Secretary of the Navy under Nixon. I worked for him again and then he got elected, and I was the 40th or 42nd lawyer in this historic old firm, and now it's close to 1,200 lawyers. How times have changed, and that bloody machine runs our lives over there, those computers. It's a pleasure to see you, Professor.

Young

Thank you very much.