Transcript

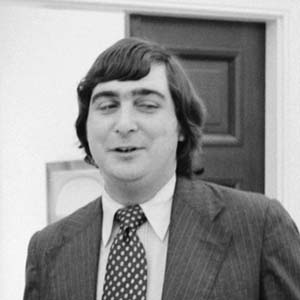

Young

I want to welcome Patrick Caddell and put this reminder on the tape about the ground rules of this oral history session. What’s said in the room doesn’t go out of the room. It is off the record. The only person to see the raw transcript when it is typed will be Mr. Caddell and at that time we’ll ask him to review and edit the transcript in such a way as he thinks necessary for its use as source material for some monographs on the Carter Presidency that would be commissioned by the Center. I’ve asked, and Mr. Caddell has indicated I think, that he would like to have this be a very candid discussion. The specific ground rules he would want to impose on the use of the materials would be made after he sees them. With that let’s begin, by inviting you to tell us a bit about how you got involved with Jimmy Carter and the Carter White House, and a general overview of your role, responsibilities, and functions over those years that you were associated with him and people on the staff.

Caddell

OK, thank you. I guess the easiest point to start with is just to explain my relationship with President Carter and where it begins. It began actually in 1972. I first met President Carter during the McGovern campaign. I was just out of college and working in that campaign as his pollster. In June of that year prior to the convention we made a swing through the south, sort of show-the-flag-for-whatever-purpose—it seemed like a good idea at the time—and one of the places on the itinerary we stopped was in Atlanta where we spent the night. Senator McGovern stayed at the Governor’s mansion and Governor Carter at that time specifically asked that I come with McGovern to the mansion. At that time, Governor Carter had been one of the leading movers in the sort of stop-McGovern movement so this was some effort at reconciliation in the campaign. I had done a great deal of my thesis work in college when I was at Harvard on southern politics and the change in southern politics. Particularly the Wallace vote and what it would mean, the long-term and short-term implications of those changes on the south. So I had studied Carter’s situation in Georgia and that whole new face election that took place in 1970 in which so many new faces, Humphrey and Chiles and Askew and Carter and others, came out contrary to the assumptions when that period began politically.

What happened was that the Governor asked me to come, we all talked about politics and the political situation, and then he and I and a few other people sat up in the kitchen until about 3 o’clock in the morning talking about southern politics and his election and the country, and got along very well. That’s where I first met Hamilton and Jody. Later, I would see him at the convention, including when they were running a campaign for Vice President that managed to pass me by. This later became a subject of great humor in ’76 and after. That was really the beginning of the relationship.

I knew the Governor in ’74 when he headed up the campaign project for the DNC. I was one of the people that was contributing occasionally or periodically to that effort. And we had talked. I had started my work even when I was in high school in Jacksonville, Florida. In Florida, I’d spent a lot of time on my thesis work on the Wallace phenomena. I particularly had been involved in Florida politics, and so I started my business. There was a growing assumption in ’75 that Carter was going to challenge Wallace, who was seen as a potentially strong figure in the Florida primary. There was a consensus, which a lot of people later regretted, to let Carter have a clean shot at that. At that time, I had a larger business as well as my political business corporations. They approached us about doing some work for them in ’75 on Florida with the understanding that I was not yet prepared to make a real campaign commitment to anybody at that point. We began to get involved in the campaign in Florida. In the fall of ’75, I spent more and more time with Carter and talked to the other people. That just began to emerge by late ’75 as I was going to be involved with the campaign. By early ’76, I was the campaign pollster. I was the only person in the campaign at that point who had had any experience in national politics whatsoever. There started then what was a very small, and would stay a very small, command structure, not only through ’76, but actually through all of the political decision-making right through 1980. This was essentially Hamilton Jordan, Jody Powell, Gerry Rafshoon, and myself supplemented and complemented at various points by different individuals. That would become the real center of the political decision-making, and I got into it very early. I was the only outsider at that point, or even later I think, who operated at the political level. That was partly because I had an indispensable political role in the campaign in which I was the source of most of the strategic information on which decisions were being made. Secondly, there were a lot of very close relationships that had been developed in that period. I’m originally a southerner—my family is southern for almost 150 years in South Carolina and so forth—so there were some cultural affinities there that would prove to be important. I functioned through the ’76 campaign as the campaign’s pollster and one of its senior advisors.

I think this is important because it becomes a basis for our relationship all through the administration. The President in 1976 ran essentially a thematic campaign or what I would describe at the time much to the anguish of many reporters as a thematic campaign as opposed to a campaign that was simply a collection of issue positions. Those themes really came from Carter. I enjoyed a relationship I suppose that was partly sprung from this shared perception from his two years out in the country and my own survey work and so forth of where the country was, what it was looking for—the sense of these things. I had a very strong and intense commitment to those ideas, as did the President. I functioned, if you will, sort of as a sounding board for him on those ideas throughout ’76, both in terms of the surveys and also in the formulation of how we would articulate those. At the end of the ’76 campaign I made a decision; it was a mutual decision. Actually it wasn’t much of a decision; nobody asked for it. I thought about it and decided I didn’t want to be in the administration. I talked to the President once right after the ’76 campaign about how I did not want to go into the administration. I wished to stay out and continue my own business, but would be available and involved. So I did essentially two things with the administration during those four years. One of them was the polling through the Democratic National Committee, until the campaign took place in 1979, on whatever research we did, which depended on the flow of dollars that we had and anyone’s interest in knowing what was going on. The other role that I played was as a political advisor to the extent that the political structure, the political decision structure, remained in place in the administration. I was really attached to that and was involved in that. The third role I played in the administration was being perhaps its greatest internal critic. I sat on a very interesting perch, which was inside and outside at the same time. I had a very particular relationship with the President and I think this is important to say because of the way the staff structures worked. I always had direct access to the President when I chose to exercise it, which was sparingly. Nothing I wrote went to the staff. Nothing was ever processed through paper. I could deal with him directly. I could see him any time that I wished. It was a standing instruction to that effect, though I tried not to abuse that. And so I could deal with him directly as well as with members of the staff, Hamilton and Jody, in particular.

Young

This relationship of access was true throughout?

Caddell

Throughout except in those periods when I was in the doghouse. But that was not because of any staff interference. That was simply because of a question the President would have. I suppose you could characterize it either charitably or not, as part of his intellectual character or at least, I perceived my role to be that way sometimes. This was mainly because I was in a position both as a political advisor and on the outside—inside to be able to say or offer, I thought, criticisms with the relative safety of the secured relationship that other people could not or did not see from their perspectives. I hope one of the things that we talk about is the White House staff and the way the White House operates. It’s so hard to understand a lot of things that take place unless you can get a feeling for what it’s like to work inside that bubble all the time and be influenced by that environment. I think it is one of the most deadly things that happens both to the staff and to the President in terms of their perception of the world. Not only was this true in this Presidency, but in past ones and in the current one going on. That is as brief as I can express my role.

I would be starting in late ’76. I went through a series of periods, but the only one that’s ever gotten visibly above the surface, was in ’79, in terms of the Camp David summit. Actually, those kinds of discussions and those kinds of criticisms or approaches or whatever flowed pretty consistently from 1976 all the way through with the President, but there’s been very little knowledge about that. My role inside with the White House is a very amorphous and undefined one. I would come in on particular issues, particularly when there were speeches involved or large policy movements, for instance on energy, the Panama Canal, and SALT, where there was issue strategizing that involved the public in one sense or involved the President’s presentation. I was involved in those. Occasionally, I would be involved in discussion on substance, usually if I interjected myself—that was most frequently on economic policy or the lack thereof, particularly during the period ’78–’79. There were, frankly, fairly crass political reasons as well as substantive reasons. We were being damaged so badly by inflation and the economy, and secondly, by what became a growing and eventually fulfilled apprehension that we would end up producing a negative economic circumstance in an election year. I had argued from the beginning that we had to avoid this, particularly a recession, under all circumstances for reelection. So I was in and out. It was a very informal thing, and my involvement would or would not arise based on the issue, the involvement I wanted to have, and the tensions of the time. That was the rough background on my relationship. I don’t think there’s been very much public understanding of that relationship for the particular reason that it was neither in the President’s interests, in my interests, nor was it in the staffs’ interests to talk about it. So it was never really made very much of.

Young

We will come back to this later, but one of the things that I wanted to know and have a preliminary question about is I believe I heard you say that from very early in your relationship with Carter your views of what the country was and what it was looking for were on the same wavelength.

Caddell

Yes.

Young

Did you discuss this often with the President?

Caddell

Yes. We discussed it not so much in a formal way.

Young

With the candidate then?

Caddell

With the candidate. It was easy with the candidate because he was much more attached. In the White House years, it became much more difficult to culminate in ’79 because my feeling was that the President had lost, and I argued this vociferously with him, touch with the country, had lost the understanding of his own mandate, and we were running grievous risks because of his losing focus. This was partly because Jimmy Carter is, as most politicians are, a visceral politician. He always did better when he was out where he could feel people and deal with them. There’s a chemistry that really successful politicians have that really becomes their lifeline to direction and stimulus. That is, almost by definition, excluded inside the White House, both by the agenda that the President faces, the issues, and the imposed isolation of the office. For someone like Jimmy Carter, that was just deadly because he began to lose his sharpness and the perception of why he had been elected and what he had been elected to do. That became a great source of discussion and division. It wasn’t a great source of division for a lot of people, but from my end that was a point of great concern.

Young

Can you just briefly state what you and he thought after the election. What was his mandate as he was preparing the transition and the move into office?

Caddell

Well, I think if you go back and look at it, this would reinforce in a sense what he had said in ’76 in the campaign speeches. This is always the problem with retrospect. It always looks simpler afterward than it did at the time. As I said, we ran a thematic campaign, which is very different from the kinds of issues and things that the other Democratic candidates were campaigning on in 1976. Jimmy Carter had positioned himself as the outsider in the field. You have to understand that he had no other choice. My theory all along was that if the country was looking for someone who was best qualified in terms of the experiences of government and understanding the machinery of government, then Carter would lose because he was obviously the least qualified person. He was a one-term Governor from a southern state, a region of the country in which the Democratic National Party was nonexistent. He had no real ties with the structure of the Democratic Party. The national Democratic Party is essentially a northern, Midwestern, and West Coast Party. He had no tie-in with that at all. He was not even in office. He had never held federal office. He had never been involved with foreign policy or most of the issues. In order to win, he had to articulate a sense of what had happened to the country through Vietnam and Watergate. If you go back and look at those speeches that he gave early in the campaign, he would talk about the damage to the country, its psychology. He talked about what had happened to government and politics and how isolated Washington had become from the people; he, in fact, was going to restore that. Essentially, what he was running on in the campaign was that the country had been psychologically devastated by the previous decade of events. He was offering himself as a healer of that, something that was not inconsistent with his own personal background. He had a very deep feeling about this. This was not a campaign tactic. Jimmy Carter, in my opinion, had the best sense of what the general concerns of the country were in 1975. They were not just about unemployment or about energy or about the economy or any of those aspects. They were about what had happened to direction in the country, what had happened to America’s sense of its own position in the world, and where it was going. In that uncertainty he really moved to fill that vacuum, to reassure people. That’s when he gave these early speeches, which a lot of people felt were quite amusing. I too thought it was a little strange, until the first time I heard him give a speech in which he would talk about giving the country a government as good and decent as the people, and restoring it as a government filled with love, and so on. I mean he was touching cores that were not issue specific, which became very difficult for the press to write about or for people in Washington, who thought this was a very strange sort of thing, to understand. Nonetheless, it was obviously being met with enormous reception, given the difficulties and obstacles he had to overcome in the country.

I had had that sense that that’s where the ’76 election really should take place and really what it was about. He had that sense and so that was where the reinforcement came. I felt that, and there’s a paper that I wrote about it at the end of the ’76 campaign. It was leaked in the spring, for some reasons inside. I’m still not exactly sure why it was leaked. It was an effort to really do an overview, which the President was very fond of at the time it was written, about why we had been elected and what it meant. The thesis can best be described in this way. I think you can view historically the President’s role. I think it’s based on historical circumstance and disposition. Usually people are in office not by accident, but because they in fact meet some need of the public. A President tends to be either the leader of the government or the leader of the society. That’s the whole duality problem of being chief executive and head of state. There are very few Presidents you could point to historically who could fulfill both roles well. Franklin Roosevelt was an exception to that. But I think if you went through and used that rough rule of thumb, you would see John Kennedy was most successful because he was viewed as a leader of society, which was why I think he suffered so much in retrospect in terms of his accomplishments or lack thereof as a leader of the government. Lyndon Johnson was the exact opposite. LBJ was much more the efficient implementer of programs, and running the executive branch and what have you, and much less of the other. It seemed to me that Carter was elected in fact to lead the society. That that was the mandate that people had given him. He was to make things better, not just in a governmental sense, but in a general psychological leadership sense. He was also supposed to run the government, but it was the secondary concern. And I think the tension began—and what I argued in December of ’76 what concerned me the most—because while we had gotten elected with a mandate to lead the country, we were about to embark on taking control of the executive branch and running the government day to day. That switch in roles was going to be very difficult for the public to accept. My own personal feeling, and I articulated this through most of the time, was that much of what we suffered in terms of disappointment with the public during the first several years of the administration sprung from that lost contact with our mandate.

Young

Did Carter offer you a position in the administration before the inauguration? If not, did he indicate to you that he wanted a continuing relationship, and what were his thought about what that ought to be?

Caddell

We met in Plains a couple of weeks after the election. I went down and spent several hours with him. I told him at that time that I wasn’t interested in being in the administration, in case he had any questions about that. There was a lot of discussion going on about that publicly and I hadn’t had a chance to talk to him about it. There’d never been any presumption in my discussion with Hamilton or anything about wanting to do it. He is the one that insisted at that point that he wanted me to stay involved with him, to always deal with him directly, to try to continue that relationship that we had had in the country and to keep in touch. He was already very concerned about losing touch with that. He really wanted me to be involved as much as I chose to be involved, and neither of us had any idea what the hell that was about.

Young

But in terms of your having access to him and being a personal advisor to him—

Caddell

That was laid out at that meeting.

Young

That was laid out at that meeting, and it was communicated to the rest of the staff?

Caddell

It didn’t have to be communicated much. They generally presumed it, and it was almost unspoken. He and I laid that out then and I assumed he had translated that, so no one ever asked.

Thompson

About your relationship with the President, and that of the President with the society at large, did either you or the President have any models for that? Was it ever mentioned that this kind of personal advice to the President could be had from somebody on the outside who had worked for some other President? Was it also ever discussed in general, as apart from Wilson seeking to go to the country on the League of Nations, whether a President had been able to lead the society as a whole successfully?

Caddell

You have to understand the circumstances at the time and it’s the kind of hubris that sets in with any success. I’ve seen it now with two different campaigns in terms of nominations and one administration and I’ve been watching this one currently and it seems to me to fit some of the same patterns. First of all, there’s a lot less thought given to sitting back and reflecting on a long-term basis about those directions. There’s so much to be done immediately and it’s done from a presumption that we have been elected and we have been anointed—I shouldn’t say elected. There is a sense that takes place and it’s human nature, really. It’s not unique to the Carter administration. We’re here, we’ve been selected, we know what we’re doing. There is a great lack of using history as a base point in any practical politics to measure what you’re doing. It intensifies incremental movements rather than long-term strategic movements and thinking. We had not discussed whether it had worked or not. I had lunch with some Washington reporters, an off-the-record lunch at the City Club when it still existed, in which we were discussing, in early January, what my role was going to be. They all said that had never been successful. Nobody had ever been in my role. You were either inside in the flow or you were outside and not in the flow. I thought they were overstating the situation. I would think less so later. I would always come back to that conversation because it seemed to me that they had been fairly accurate in many cases about not really knowing, if you weren’t there day to day, what was going on. I often missed much of the decision-making going on. We never really discussed the difficulties of trying to maintain that, first of all, because we had no perception of what the job would actually be like. None of us really understood—none of us had any experience with it—what the White House would be like, what the pressures would be like, what the day-to-day reality of being in an administration would be like. So we could blithely make these statements without any reference to that.

Now, in terms of leading the country, the problem we had from the very beginning seemed to me that we never did come to grips with that. That’s one of the things that haunted this administration throughout, in my perspective of the public. It really was affected in the staffing of the administration. One of the points that I was always most concerned about can be illustrated with an anecdote, because it’s a good one and it serves this purpose. The President came to Washington as the President-elect several times in the transition and stayed at Blair House just before his inauguration. He was meeting with the transition teams about what we were going to do about the economy. We had a meeting in Plains of the economists. There was a particular discussion that took place. Most of these people had now been appointed to slots in the administration or in the White House. They discussed what the agenda issues and problems were coming up and the President had asked me to participate. The President got very angry in the discussion. People were pushing him in the areas that he had not thought about and was not interested in. It almost seemed to him to be a series of individual agendas that people had been storing up for a number of years that they wanted to get exercised without any master plan. Literally, each department and area people said, “We’ve got to do these ten things. They are now top priority items that we must do.” There was an hour of that. When he came to office—in retrospect it’s hard to remember this—he was a very frightening figure when he arrived in Washington. The fear in late 1976 was that the man was going to be uncompromising, tough, and it was really a question of whether he could get along with anybody. Later, the perception was the entire opposite. But that was the perception coming in. And it was reflected that morning. He was very angry at the discussion. Carter has certain physical attributes that show themselves when he starts to get angry and one of them is you can see tension in his face in his veins and his neck, and he was very upset by what was happening. I could see all during the meeting these people were digging themselves in deeper and deeper and deeper and they were really not cognizant of that. At the end of the hour the President really exploded. The President-elect exploded.

He and I had a discussion afterward. I said I thought it was a frightening situation because what seemed to be lacking was any sense on the part of the people who were now being brought into the government of why Jimmy Carter had been elected. The bulk of these people were Democratic activists who had been waiting to come to power in any Democratic administration; in fact, they would have been swatted in with almost any Democratic administration elected. There had been no argument or discussion about “why are you here and what are you supposed to do.” It was a set of, “we’re going to institute all these things we’ve been waiting to do for all these years.” The President did not impose his ideas at that time in the discussion. I only bring that up because it was vividly burned into my consciousness at the time, and he and I had a conversation about it afterward. I was just appalled, as I gather he had been, that they didn’t seem to understand what we had just come out of and why we felt we had won or what we were supposed to do. Part of the problem was ours, because we had never developed that either in the sense that you’re referring to, which is exactly how do we translate that into that role of leader of the society as President. We hadn’t given much thought to that, other than the rhetoric and emotional ties. We ran into that difficulty right away, which was one of the hard practicalities of staffing the government.

Through most of the campaign, the decision-making, the major drive, the center of the campaign’s drive and intellect was held by very few participants from the very beginning and throughout the election. It was not a very expansive group, and did not expand very much even in the general election for which there was a lot of criticism. That group shared a basic sense of why we had been elected, but it was not something we attempted to educate anybody else on. That’s why I wrote that memorandum at the end of 1976. It was really directed to that problem of saying, “Look, you all need to understand how we got here and what our particular political difficulties are on the horizon both short and long-term.”

Young

Who were these people that were presenting him with the government’s and the Democratic Party’s agenda? I’m not asking you to name them, but just to place them. Were they departmental people, Congress people?

Caddell

They tended to be departmental people.

Young

Not Hamilton and Jody?

Caddell

No, no. In fact, in the meeting neither Hamilton nor Jody nor Gerry. I was the only person from the campaign core that was in the meeting, and I was self-invited. The people who were there were essentially people who had headed the transition teams. They were already slotted for department jobs or White House slots. They were the programmatic people who had been working through the transition both before the campaign, and particularly intensively after the election.

Thompson

Could you say just one more word on the content of this unique personal relation. I have a friend who—we all had him as a friend—who was called down a week or two after the election and he had 20 or 30 items to discuss with the President. On the basis of his long experience, he thought there ought to be somebody in the administration who would keep the President from making a fool of himself, a wait-a-minute man. My question to you therefore is: was yours that role, a cautionary role or counseling role, or was it an idea role of new horizons and new things to do, or was it some combination?

Caddell

It was probably some combination. I had some responsibility on the political end for raising caution flags to warn against doing things that were going to be destructive, and later to be concerned about the day-to-day specifics, or the drive to do something without any long-term perspective of the impact or perception of that on his consistency with other long-term efforts. But initially it was, and most of the time it was, a combination idea and cautionary role. The cautionary part was grounded in politics. One of the luxuries that I always had in this relationship was unlike most of the people who were in the administration and involved in substance. The real problem of this administration in the beginning was a separation of its substance and its politics. If anything in the beginning pointed to what would be a problem, and it flowed from the President and from the personalities of those involved, it was to separate the political decision-making and perspectives from the substantive perspectives. The political people, or Hamilton, Jody, their staffs, and people related to them, were not deeply involved or interested in the substantive discussions on what his economic policy was going to be. Hamilton, for instance, never really had, and would I think openly admit, that he never really had an interest. The substantive people were not responsible for our political fortunes. I view politics, by the way, not simply in reelection. I don’t mean to simply be crude politically, but my theory had been, as that memo in ’76 articulated, that in order to be effective as a President, we were going to have to maintain a level of political strength and popularity in the country in order to overcome some of the institutional roadblocks—which I didn’t understand and would come to understand a lot more graphically later—that we would face. There was a need to blend the two together, to understand your politics as an expression of your ability to maintain support, and to educate the country and keep it with you. This was important as a political lever to move your policies through. We never really did address that in a structural way, nor did we ask, “How do you operate that?” Political decisions or political concerns would take place in a small circle of people who would raise concerns about politics and argue with the substantive people, but the substantive people would go on their own when they were particularly charged with responsibilities, and ordered by the President to do what they felt was best without reflection of politics. There was a natural and immediate conflict that took place there as well, creating what I would call a huge vacuum. There was no one who really had a strong foot in each camp.

The reason that I could, from the outside, offer ideas or suggestions or be as outrageous as I chose to be in terms of direction or substance or as a gadfly was because no one could question that I was in a political sense, that I lived in the real world. Nobody could argue that I just had my head in the clouds. I obviously had been through that, I had proven that I was as tough politically as anybody else and could accomplish as much politically when it really got down to it. That is what always blocked up the substantive people. Substantive people, no matter how able they were inside the White House, rarely were ever in the councils of political decision-making because they never came with the credentials or the respect as political thinkers. In some cases, that was a well-deserved understanding. The negative side of that was that there was never an effort to educate or to really mix those together. It is not from a conscious lapse at the time, but again you have to understand the psychology of we’re going to go in there, we’ve been elected, we’re going to do this for the country, we’re all ready to go and boy we’ve gotten elected and it proves how good we are. It is, I think, one of the dangers that overtakes people.

Strong

Is there some relationship between themes in the ’76 campaign and southern Democratic politics? Why was it in that campaign that Jimmy Carter was the only one articulating those themes?

Caddell

I don’t think it is and given my study of southern politics, I’ve hardly argued that it is necessarily inconsistent, it was just a reflection of that. Stylistically, it was in a sense religion and Southern Baptism. When I did my thesis work at Harvard on southern politics, what I really ended up landing in was the middle of the influence of Southern Baptism on the politics in the region. Once you got there, at least for what it was worth, it seemed to me you could get in there and unravel a lot of things that related to style. In a sense, Carter was out of that stylistic milieu of being a Southern Baptist, that kind of rhetoric, that kind of belief in relating to a long purpose and goodliness to politics. That was helpful. That was uniquely southern. Most southern politicians didn’t understand it either. Carter was the first one who was really thinking it through as it related to a national political set of circumstances. But clearly he was best equipped because of his background in that cultural background. He was at ease at being able to talk about these things because he came from a background where that was understandable and acceptable.

Wayne

Moving from the campaign into the Presidency, you noted that you had frequent and increasing conversations with him about the fact that he was isolated, that he had lost some touch with the country by the nature of the Presidency. I’m interested in how he reacted to that comment? Did he react defensively? Did he show surprise? Did he want to know what he should know? What was the reaction?

Caddell

It depended on the time and the incident. Sometimes his reaction would be defensive and say, “I’m not, I think I understand.” And sometimes it’d be, “You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about,” which was also probably true. But oftentimes it would bother him a great deal. During the course of this Presidency I wrote a series of memos, for which I became internally noted. It was a series of four or five really long memos at various points in the administration. Usually they ran anywhere from 40, 50, 60, to 70 pages for him in terms of what I thought was happening and why. And each time, one of those popped up and had an impact, at least in the short term. It usually came when we were not doing well, so there was a real concern anyway. It was coming at the right opportunity and he would focus on it. In fact, the first time was in the fall of ’77, October ’77, and the next one was March-April 1978, which would lead to the first summit meeting at Camp David. The first real summit meeting staff meeting took place in April of 1978, when Carter was going to change the way he did business. If you go back and look at it, that didn’t come out of the blue. It really came in response to a long memo that I wrote at the time in which I made some very strong suggestions and quite graphic language that I thought the President was on his way to being a failure and the reasons for it. That certainly got some response from him.

Wayne

You mentioned also that there were times when you were in the doghouse with him. Did he ever get mad at you because of what you told him, or about how he was doing or how the country perceived him?

Caddell

Yes. And rightfully so. I always felt that somebody should be for whatever the risk was, and I had nothing at stake. It seemed to me, after watching the White House operating and watching people go into the Oval Office and not tell the President what they all felt, that somebody ought to be willing to throw all caution to the wind and be somewhat more candid with the President. I felt that we had a particular relationship that protected me from the long-term dangers of that, which it did. But like any person, when you’re up to your neck in alligators, it’s hard to remember your purpose was to drain the swamp. And here I keep coming in to ask, “Why have you not yet drained the swamp,” and he’s sitting there being surrounded by things, foreign policy problems, I didn’t know about. And here I am hammering him. Sometimes we would get into strained situations. That was most evident in the fall of 1978, and in the first couple of months of 1979, in fact.

Young

You had almost a premonition during the transition of the danger of the President losing touch. Was this a view unique to you? Were there others among the political advisors who perceived things the same way?

Caddell

There were some general concerns by some of the political people. Never, I think, as strongly felt or at least as conceptualized as I tended to do in that memo. That initial memo in ’76 really became important during the first hundred days. The thesis of that memo was accepted by the political people. There was a general consensus, and the President certainly agreed with it. I argued that we did not have a mandate, that one of the things that was unique was that he was a post-Watergate President. We were the first post-Watergate President elected. Looking at survey data, the automatic benefit that came from being elected was the halo effect that took place from election. The Presidential popularity that seemed to exist with past President-elects was not happening to Jimmy Carter. In December, peoples’ perceptions of Jimmy Carter were basically no different than they had been the day of his election. And this, by the way, also followed with Reagan. I now have a long set of theories. I think something has changed with the Presidency that puts Presidents in an extraordinarily difficult situation of being able to maintain a public base. The first glimpse of it is in that inability to be given that benefit of the doubt or that brand of euphoria. It seemed to me that by January the numbers still were not moving, and that we were going to have to somehow build our own honeymoon. We would have a natural honeymoon coming up that we would have to somehow build that expansion of real popularity that seemed to be in suspension. That’s when we first came up with the program in the first couple of months. This is when we got into this. It’s very important because time-wise it becomes a real detachment. The day the energy speech is given, we walk away from this. Those first efforts at the fireside chat, the sweater, the walk down Pennsylvania Avenue, the radio show we did, the town meeting in Clinton and so forth, all those were thought out and recommended in that memo basically, except for the walk, which was his idea. Jody and Hamilton, we all agreed that we needed to do these things. We needed to build up that support; we needed to relate to why we had been elected. While it wasn’t all conceptual, I think on everyone’s part, at least initially, there was a perception we had to do that. My feeling was that we essentially had to buy time. We did not know what we were really going to do substantively and that we needed to expand and reassure people and build our own honeymoon and that was in fact extremely successful. Now we faced enormous criticism. Later it would seem to me that that was one of the real dangers. We had listened to the criticism right in front of us without regard to the success we were having out in the country. This was not just to improve our popularity but in fact to assure people that they felt comfortable that he was going in the right direction and so forth. He was getting through as a leader. We got so much criticism about being so stylistic, and that’s the period of time when my memo had gotten leaked. We never know for sure, but there are some suspicions of what happened. As with most things, it was leaked with a purpose, which was to in fact put us in a more defensive posture in the sense of these things we were doing.

But what happened the day the energy speech would be given is a real departure point, in my mind. From that moment on, for the next year or so, Carter would never again do those things or use those tools that he had so effectively brought to bear in his first couple of months in the Presidency. They would totally disappear from the table. And they would disappear because in fact we went to substance with a vengeance. I mean we literally went from one extreme to the other extreme. It was not a blending. And that goes back to the inherent division between who was running which agendas.

Young

You made a statement earlier that seemed to suggest this dilemma or problem about how to maintain public support so that your policies could move forward was in part the difference between leading the country and doing the business of governing. I believe you said, “We never addressed this problem in a structural way.” My question is, how could it have been addressed in a structural way? What means did you have in mind? What means did you advise? What did the President think about?

Caddell

What I’m saying is I didn’t advise any particular structural means any of the time. I was saying here are some things we can do. I think there was general agreement on the part of the political people by the end of the administration. Hindsight is very helpful, experience is a great teacher. One of the problems that we had and one of the advantages we had the day he was elected was that the city of Washington was terrified of him. Remember, he had not been the first choice of his party. Most of the institutional leaders of his party originally opposed him. I was in Washington two days after the election, and I felt like I was in Paris. The day before the Wehrmacht arrived. A Democratic city should have been in euphoria over the coming of a Democratic administration. I was speaking to a consultants group. All the consultants at the end of every election get together. The mood I found was very different, very apprehensive and it was that he was an outsider, he was totally unknown. Remember he had gotten elected by stomping all over the Congress, basically, for which there was real resentment, and the city of Washington. And yet, he was now the President of the United States. It seemed to me that this would affect our relations with Congress. It seemed to me we never made a decision of how to come in and deal with them. You can see the institutional operations. Do you come in and attempt to? We never thought it through. Jody and I would discuss this later on, this being a real problem we had not thought through when we began the Presidency. We didn’t know. Should we have come in and gotten very tough from the very beginning and drew the line and just used that advantage that we had, which was a fear about him, and drive the thing? Or should we have come in and attempted to coop the city, to coop the power structures of the party and the Congress? What we ended up doing, as we all later agreed, is that we did it in—and pardon the expression—a half ass fashion. We did a little bit of this and little bit of that. But we never had a strategic idea of, look we must come in and take charge, or we must come in and make allies of these institutional leaders. So we would get into the situation of the President getting with the Congress and congressional leaders and promising cooperation, almost giving the store away from Day One trying to convince them that he was going to work with him. And yet, at the same time, from a certain sense of exhilaration and superiority of winning, we were looking somewhat askance at the society and the structure of the city itself, without regard to whether people in Washington liked us or didn’t. We were really working against ourselves in that way.

Young

Is it fair to say that the problem was dimly perceived as to how you got hold of Washington, but not sufficiently, clearly perceived or anticipated as to a definite strategy for dealing with the problem?

Caddell

That’s right. It was never perceived as enough of a problem to have a coherent strategy. It was dimly seen and we had these discussions that I’ll give you some of the anecdotes about. But we were so busy filling the government at that point. The President’s time was preoccupied with cabinet selection.

Young

And there was this vague feeling that it may not be such a problem because after all we won the election.

Caddell

Exactly. Look if we can win this election and become President there is nothing we cannot do. It’s a superman theory of coming to office. You just believe that all things will bend to your desire or to your needs. Eventually, it was like a movie script in which everything would end up and we’d all ride off into the sunset and everything would work out positively. It was that sense of confidence that you need, but I think in retrospect, we agreed it was a little naive. And it was. It was an incredible achievement. Nobody had ever done what Jimmy Carter had done in terms of being elected President, so there was no reason to assume that merely running the government should be a problem. It’s funny now, but in a sense you have to understand how much those opinions really mattered. There was some initial concern about the appointments for instance. I’m saying there are pieces of this you can see whether it’s Carter being upset at his staff people. We said, “We’d better do something about expanding our popularity here, getting in touch with people, giving Jimmy Carter a lot of momentum at the beginning of this before we know we’re going into energy,” while we knew from the very beginning that we were going to be in a position to go with a major energy program.

A lot of problems were over appointments. Now Presidents don’t have to deal with, as their staffs do, this great fight over who would be in power. There was a great discussion at the time because there was a lot of bitterness on the part of the campaign people, as there was in the Reagan administration, over not being given positions and positions going to people who had not been involved in the campaign. Again, there was no theoretical understanding of saying, “What are the trade-offs?” Do you take people from the outside who you think share your perceptions? Reagan has some advantage in this actually because this is an ideological base to the people who share his ideology. Do you take people who share the direction you’re going who are from the outside but who don’t have the experiences, or do you go into the establishment structure and take people who have the experience?

Caddell

In February we got creamed by what I described at the time in an angry letter I wrote to the President as “resume government.” I said essentially, “I think what happened is that everybody got together in Georgetown and agreed that they would all push each other’s resumes and had taken over the second and third levels of the government.” The fact is we were finding that we were. Hamilton was irate at the time, as was Jim King, who was doing the personnel direction. We could not get our cabinet people and our other people to give any help at all placing our political people. Understand my problem, we were angry because we had a lot of people beating us over the head who had worked for us and were friends of ours and who deserved, we felt, to be in the government. What we were not saying at the time, and it was again only dimly seen, was in my letter at that time. I was the first person to articulate the problem that we had a government full of people who didn’t understand why we’re here, and seemed to be very unsympathetic to anything that was involved in us getting there. It goes back to this. But we had not thought it out as a strategic thing of saying, “Well gee whiz, how are you going to staff the government, where is the line you draw between bringing in people who are experienced and bringing in people who have some instinctual idea of what your vision or your goals are or even why we’re here?” We had that wiped out very early on and we suffered with it. A lot of what would later happen in the administration would be the proverbial closing the barnyard door after the horse is gone, trying to reestablish control of the appointments processes and the political appointees. We allowed department heads to make their own appointments basically. We lost control of the departments.

Young

You say we. Who? The President indicated, consistent with many of the statements he made, the importance of the cabinet and cabinet responsibility and the notion of allowing a fairly free hand on appointees. Wasn’t this the President’s wish?

Caddell

It certainly was the President’s wish. He was out making these statements about how grand this was that we had never really thought through the implications for actually governing. When we did, we were already too late. I’m saying you never understood where the tensions would come until in fact they had already come and gulped us.

Young

The opposite swing is the firings.

Caddell

The firings would come in the opposite swing, but would be rooted very much back to those very first appointments because Joe Califano and Mike Blumenthal and others had gotten themselves in real Dutch with certain people in the White House from the very beginning by taking the President’s mandate to appointments in their own departments. In the view of some of the people in the White House, they ran with their departments without regard to the President. So the roots of the firings go all the way back to that period in January and February.

Thompson

In this exchange with Jim and Steve, especially in the beginning, I got a glimmer, maybe it’s wrong, a little flashlight picture of Carter that I think we’ve not quite had before. Let me see if I can highlight the question by comparison. You’ve talked about the anger, about the indignation. We have an unpublished manuscript on Lincoln. Lincoln’s leadership detachment is mentioned as a very central quality, almost without precedent. Here was a President who spoke about the unjustified and unnecessary war; at the same time, he was trying to raise an army. He said when he came to Washington, “Many of you are surprised that I’m here. Most of you were against me. Most of you had different ideas about the issue that is most important, slavery.” You almost had a feeling in the case of Lincoln, for better or for worse, that he was standing outside of himself looking at this issue. Carter seems, with all the belief and trusting of the people and with all the humility, anything but detached as you describe this anger. In trying to understand him as a leader, is there a different quality, is there a lack of this Lincolnesque detachment that the biographer writes about?

Caddell

I think so. How much of it is Jimmy Carter and how much of it is that now this is a very different office than it was a century ago? I’m not sure. You have to make that decision. The problem you get swamped in is one of the things that always concerned me and others who were with the President. I never got any understanding when he would ever have time to reflect on anything or to be detached, even if that was his instinct. He had spent two years on the campaign trail, literally going day and night as hard as he could possibly work. There was not a lot of time for reflection. Of course we suffered from it because when we had made all these commitments, no one had had time to really reflect about coming to Washington and being the government. One of the things that happened here—and I never really discussed it with the President because it’s only struck me in recent months—and something that I would really like to talk to him about, is I used to argue with the President that I thought he was a different person than when he had gotten elected. He had changed in the office, and I did not personally think for the better. But you have to understand I was sometimes hysterical in these times. You just generally don’t go around saying these things to Presidents. I’m not sure in retrospect how much the problem was this lack of detachment, and I’m not saying his personality thing. I’m also saying he was driven by the office, the inability to ever sit down and reflect, “We’ve gotten elected, now what do we do?” We had never been in motion before that. Remember the transition planning that Jack Watson headed up, which caused an enormous problem the day after the election. He was off in isolation at the President’s instructions, totally separated from the campaign. These people are supposedly planning his government or doing his work, in the meanwhile the people who are in the trenches, who are in fact living daily with what’s working or not working or that sensibility, are totally isolated from that process. All this was the President’s own decision exactly to do this. But nobody ever challenged it to say, “Mr. President, this is crazy. Some day you’ll end up elected, then you’ll have this transition, and it won’t have a relationship to your election and it’ll be the beginning of a problem.” Now if I saw someone doing that, I would make that case. But none of us had the time or the experience to make those kinds of reflections. We were desperately concerned every day with getting elected.

Having gotten elected, the President woke up and realized that the whole world had really fallen on him. It’s one thing to say for several years that I’m going to be President, I can handle it, I’m confident and so forth and then to wake up and have it in fact put right in front of you. The President began to become much more cautious in a lot of his own appointments, in a lot of his own actions. He was different from what he had intended to do partly because that force and the battering of demands that were going on at the same time were out there. You make this appointment to do this foreign policy, what are you going to do about the economy the minute you get here, and so on. All during the transition, you could still see the flares where Carter would not want to go along. For example, we had the meeting with the economists at the pond house in November, which became an all-day session most noted for the fact that the President did not serve anything except water. Those of us who been through the campaign understood that ahead of time. But we had all these people who were on display, if you will. The President was extremely interested in these discussions. I again invited myself and did a lot of work on consumer studies, so I had a real interest in the economy and consumer behavior and attitudes. I was very intrigued by what happened. We had a consensus meeting in which everybody spoke to the President, all summed up by Charlie Schultze. This went on for six hours. His attention never wavered, which I could not understand. Bert Lance and I were in the back ready to fall asleep. And at the end of the meeting I remember everybody left and the President asked me what I thought. It was the Vice President and myself and the President, and the President said, “Well, I’m glad you came. What did you think?” And I said, “Well I just thought it was terrible, I thought it was long.” But I said, “My major concern is I don’t agree with him. The economy seems to be falling apart at this point. I just don’t see what they’re talking about.” The President said, “I don’t either,” and he said, “I’m really reluctant to go along with what they’re all advocating,” which was eventually what we would do, but to a lesser extent than was then being advocated. These were the stimulus packages for December. A month later, the Vice President said, “Well, that’s why you don’t make it. Policy in this administration, that’s why we have these experts,” which is something that I would constantly remember as we would go on down the road on the economy.

In December, by the time we had made a decision to go with the stimulus package because we had consulted everybody in Congress, all of whom agreed to do it, it was clear that we were not in a recession, that things were not as bad as they had said, that the indications I had been seeing before had turned out to be exactly right. Charlie got up and gave an explanation that was 180 degrees different than the consensus we had had a month before about the economy. I thought Stu was going to fall off his chair, because Stu and I were the only two people at this meeting with the cabinet who had been at the meeting, other than Charlie and some of the participants. I was there to brief the cabinet on why we had been elected and had stayed through this discussion. I remember saying to Stu, “Can you believe that this is what Charlie said a month ago and what we’re seeing now.” But again, we became anecdotal. The President’s first instincts were not to go the route on the stimulus. That was his own gut instinct; this was not followed. He would get beaten down. He got beaten down in December by his own people, in a sense who said that he must do this. And we ended up doing it and got in the embarrassing position of having to withdraw the thing by spring. Then again it was because we didn’t have a strategy. I had argued in December, for what it was worth. The thing I was writing about most was inflation. There some were some people in Treasury, as I now find at the end of the administration, who had in fact argued a strategy that we in fact sit very tight on inflation. We weren’t expected to solve every unemployment problem in the first two months. We ought to protect ourselves and work slowly, because then we would be able to point to progress, but protect our flank on this inflation thing. Those kinds of discussions never came up for strategic discussion about administration policy. These are all anecdotal because nobody ever sat down and said, “What are we going to do?” We were under such pressure, the Vice President, Stu, people inside the Democratic Party, the speaker and so forth saying, “You’re a Democrat, you got elected, now we’ve got to do something right away about unemployment and stimulate the economy.”

Young

It was a united front on this—the congressmen, the advisors everybody.

Caddell

It was a united front. That’s right, except for the President, who did not want to go along. The President kept saying, as he said to me, “I don’t think it’s that bad.” Carter’s instincts were much better on that, but he did not feel confident, in my opinion, to override every economic advisor, every cabinet officer, and the political leadership of his party on this point. He and Bert Lance were the only two people who basically didn’t want to go along. Lance did not want to go along for ideological reasons and the President didn’t want to go because instinctively he didn’t think things were that bad. And I know because I was in the middle of that conversation saying, look at this consumer data, this does not show the consumers are sluggish. In fact, it looks like we’re going to have a very strong Christmas. We’re going to have a big Christmas buying, which is what we had. But that model of what happened to the President began to repeat itself time and time and time again.

I would really like to ask him a question. I’m not going to bother him while he’s writing his memoirs. I thought I would wait until he got them out of the way. Later I want to ask, “How much did you feel and at what point did you feel as President,” which I’m sure he’s felt later. He’d been that way in the campaign, I understand. In the campaign, when Jimmy Carter did not want to do something, come hell or high water, he would not do it. The fight we had with him on ethnic purity, to get him to retract the statement about ethnic purity was just incredible. It stands as a marked contrast to some of the earlier actions that took place. On the ethnic purity thing, the President knew that he had not made a racist comment, knew that he never meant it to be a racist comment, and was outraged that anyone would think to the contrary that that’s what he had meant, particularly given his background. We had 72 hours in which everything that all of us had, including his wife, was thrown into that fight right to the end of the line until Andy Young finally convinced him he was going to have to do something about it. That was a relatively easy matter. Contrast that with following his instincts. All through the campaign he would follow his instincts when he decided he was right. That’s why people said he was too tough. He could really be a tough taskmaster that way. He would listen to advice and make his own decisions. We begin to see a different pattern start to emerge, when he would just get weighted down with all this advice. Part of it is the character of the President, and part of it is the inexperience of being President-elect. And another part of it is the lack of long-term strategy, not coming in with a sense of what our problems are going to be, what we are going to face right away, and so on. We were doing it all in a relatively ad hoc fashion.

Magleby

Pat, I’d like to go back a little bit to the nature of your administration after the ’76 election, and then get a sense of how you organized your business with your involvement in the administration. You’ve made clear to us in a concise way the need to have independence, which was a primary reason you didn’t want to take an official staff job in the administration. I’d be interested first in knowing if there were other reasons that prompted you to not want to join it in some official way or as some full time staff member.

Caddell

Well, the major reason is that I wanted to go back to my business. I had things I wanted to do with that. There wasn’t anything I particularly wanted to do in the White House at that point. It was essentially a personal decision. I wanted to get to things I wanted to do.

Magleby

From the discussion this morning it’s clear that you were involved from time to time quite intensively. Was your degree of involvement or level of involvement sporadic or rather constant?

Caddell

It was sporadic. I suppose it was, at a low level, constant and then occasionally sporadically came into very high volume, so I’d be doing nothing but work in the administration. You had to be careful or you could just work daily and end up being sucked into doing all sorts of things that were not very important or really meaningful that would take away from all the other things that you had to do. I would say it tended to be more sporadic involvement. I’d go to the White House at least a couple of times a week, unless we were really involved and I’d be there a lot.

Magleby

In your negotiations or discussion with President Carter about your providing him with survey information and playing the role you’ve described for us a bit, were there any discussions or conditions that he had upon you? Was it a sort of two-way street?

Caddell

Well, no. It was very informal. It’s not like we were negotiating anything. I wanted to let him know that I didn’t have any interest and he didn’t indicate that he had any either so we weren’t having a big problem. Then he defined what he wanted me to continue, which is more of a reassurance. There wasn’t much negotiating. In retrospect, I wish we had, but it was just an understanding. All he was reaffirming was something I perceived already and that most other people perceived.

Young

Did the President give you specific assignments that he wanted you to survey?

Caddell

Sometimes. He rarely paid attention to what we were doing on the surveys. For someone who had shown such a consummate interest in the ’76 campaign, it’s always one of the things that I felt was the great irony in the administration. We were always being attacked for doing surveys, which we did not do as often as I would have liked. I certainly wouldn’t like to do as many as my friend Dick Worthy is doing now. It was really the President’s overriding interest in ’76, which stopped after ’77 once he got into office. It was as though he had left that behind. It was a curiosity, but he rarely asked about that unless he had some particular thing. There were a couple of times involving things overseas when he was very interested in my finding out from source material what was involved in public opinion. Those would come to the NSC and through Zbig, or he would call me and say, “I want you to do something for me.” Otherwise, he would wait until we were in a real issue like energy for instance, when we were really trying to figure out how to convince the country to do something that it was not going to like doing and how much room we had and how successful we were going to be at convincing them that they should make these sacrifices and do these sorts of things. There it was a tool, then he was interested because again it was part of his policy operation, which was, “How successful are we at doing this?” The Panama Canal, for instance, was another one. But rarely did he show much interest in the polls himself, until 1980.

Wayne

Did you do polling for other units in the White House with poll results tied into what Anne Wexler was doing?

Caddell

Sometimes. When we would do a survey, or when there was a need for something usually. Various people had inputs in things they were interested in finding out or had some relevance to what they were doing. So if we were conducting a survey, we would try to include as many areas as we could that people were interested in. I would end up having to referee, giving them what we could do and the cost of what we could handle.

Wayne

When you say “when we were doing it,” were you doing it for the DNC or for the White House?

Caddell

DNC was paying for it; it was all going to the White House.

Magleby

And how would those reports be circulated? Was that at your discretion, or Hamilton’s?

Caddell

Generally it was at my discretion. Well, Hamilton and I would decide. People who wanted specific information usually got that. The analysis was done of the numbers and so forth. There were a lot of public polls going on too. In terms of political analysis, that was generally tightly held. The decision would then be made as to whom to include or not include on the issue. For instance, the Panama Canal had a lot to do with the State Department and Secretary Vance and some of his people. They were essentially the clients because they and the people in the White House were working on the Panama Canal with the clients.

Magleby

Would you or someone who works with you who was knowledgeable about survey research provide some synthesis for the White House or the public polls on a regular basis?

Caddell

No. Not really, I did occasionally. I would occasionally; usually I would never get a chance to. Someone would call up about a poll and be moaning or groaning.

Magleby

Polls about popularity ratings?

Caddell

Yes, they came so frequently. Sometimes I would synthesize it because there would be something in there that I wanted to get across. Most of the time this became a topic of conversation. Probably we could have done that more systematically, but the resources weren’t there to do it.

Jones

You did synthesizing across polls?

Magleby

Yes. Elements that might come to the attention of Pat that he couldn’t translate for the administration on a regular basis, maybe weekly.

Caddell

We didn’t do it that frequently. I did it when I thought it was necessary.

Young

I was interested in this point that you made a moment ago that after the ’76 election the President really did not focus a great deal of his attention on the polls. Did that surprise you?

Caddell

A little, because he had always had such an interest. It didn’t surprise me very long because he was dealing with everything substantively. Political decision-making and the substantive processes were usually haphazard. Usually they came too late into the policy formation. So it stopped surprising me. He really wasn’t interested. He was interested in being President, in substance. All of us on the political end began to live with that frustration. Hamilton, Jody, and myself were unaware that that was the kind of President he was going to be. So I was a little bit surprised. As I said, the irony was that everyone kept saying that he was running the country by polls. Either I’m a very bad pollster or this analysis is wrong because clearly he’s doing a lot of things that are clearly unpopular and he’s doing them with malice and forethought.

Young

How do you account for that recurrent image of Carter while he was in office that everything he was doing was being driven by his popularity ratings or by electoral considerations? The picture you seem to be painting is that he was paying very little attention to that. How do you account for this?

Caddell

Well I think partly it goes back to ’76. He was viewed to be a master politician. We were all viewed to be. You have to remember in the early days we were the master politicians, later we would be viewed entirely differently. But it seems to flow with the seasons. It was a real campaign operation. The press had that sense that he was always concerned that way, so they felt that that’s in fact what he must be doing. I suppose it was something that was left over from that. Also, when Gerry came about to do image stuff, which I think in retrospect was much too ambitious given how much could be done, it tended to be, well, that’s what he’s trying to do. I was always amazed by the fact that the political press in Washington particularly wasn’t more cognizant of the fact. Clearly there wasn’t any real political direction. The politics was ancillary to most things being done. That’s why President Carter was going to be a substantive President, which I was all for. I just didn’t think you could totally abandon your ability to have that leverage politically.

Magleby

Let me pursue a specific example. Panama Canal. Would you have done, fairly soon after the signing, a survey on something like that?

Caddell

Well, we started with Panama much earlier.

Magleby

OK. There was a whole lot of tension as I remember between the administration and Senator Byrd about the timing of the vote. His analysis of the polls was that if we bring it to an early vote, we’re likely to lose. “We’ve got to wait for opinions to move on this, so I’m going to sit.” Remember the President said he wanted a vote by Christmas? What role would you have had vis-à-vis congressional liaison, Anne Wexler on that kind of survey?

Caddell

Well, what we were trying to do at that point on the Panama Canal treaty was very simple. The first thing you have to understand is that we knew that we could not pass the canal with the numbers as negative as they were. This is the first time I’d even seen a public issue, except for Watergate, which was really more dangerous, which the polls resolve. In the Senate, some people were not going to move until we had removed some of the political pressure by getting those numbers up. No one was asking us to get the majority or 60 percent, but they did not want this thing losing 3 to 1. This is the first time I can think of where survey research was intended to affect public measurements as a directive of strategy. I was to find out which of the best case arguments we had in terms of putting together the case. From testing, we’d know what would most move public opinion in the short term and what would have the best impact at raising those numbers so we could reassure some of those Senators and get us in the ball game to carry the proposition. I didn’t have much to do with the decision or the vote, but I understood that we needed more time because we had to wage a campaign. There became an understanding that we had to wage a public campaign, we had to get these numbers up.

Magleby

But then why wasn’t that communicated to Carter so that in his public statements he wasn’t pressing for an early vote, which only antagonized Byrd further?

Caddell

Mainly because again it wasn’t until after that, as I remember. I don’t think it was until sometime after that that we really began to sense how difficult the public selling job was going to be. That’s when we began to evolve the strategy of going out and doing the grass roots thing, using Landon Butler’s and Anne Wexler’s operations.

Magleby

Ford and Kissinger endorsed this.

Caddell

We had the Ford and Kissinger endorsements, the President’s fireside chats, the speeches that people were giving, and all the pressure on businesses to mount a concerted effort. It wasn’t until we realized how bad the initial impression in the White House was on Panama. Maybe the opinions weren’t very strongly held and they’d just move overnight. Once we got a sense that that was not the case and that it was going to take a lot of hard work, then the strategy changed. The President sometimes operated under the illusion, as many of us did, that on these important matters people would be voting strictly on the merits of these propositions.

Young

Do you know of any instance where the President was dissuaded from a course of action because of readings of public opinion?

Caddell

Well there are small things where surveys had a bearing on not to do something more than it was to do something. There were incidents, usually small things, putting off initiatives. It generally was an infrequent thing; it was just one of the tools in what usually was a major political case being made.

Young

Would it be fair then to characterize the White House or the President’s behavior in terms of his policy initiatives, the substance and timing of them as being relatively little influenced by readings of polls?

Caddell

Absolutely.

Young

Was that true throughout the administration?

Caddell

It was basically true throughout the administration. I would talk to Stu or I would have some discussions with him, but the White House and government policy machinery was being driven in relative isolation from political concerns, except as they were brought into the table. One of the problems was that when they did tend to pop up on the table, the substantive rather than the political people would make the political analysis to decide what the political arguments were. They would often miss the real political implications in some of their political judgments because their political focus in their own policy formations tended to be interest group focused. It tended to be the people they were hearing from that would overwhelm their perception. The constituency group lacked any ability to step back and say, which is what I often said, “Whatever these groups are saying, most of their members and most of the country could care less about this issue, or the impacts are general, not specific, and your popularity is not the sum of all of the specific groups and actions. You deal with the interest groups from the top down, not from some of the bottom up.” But they would tend to exercise their own political perceptions. Their political experiences were limited, and they tended to come from the interest groups that each of them dealt with, or the pressures that they had.

Young

Which means a Washington bias.

Caddell

That’s right. Which meant that we were usually being pulled to and fro because when you did x, then you angered y and you would hear from y and then someone would want to do z and that would anger x again. I kept saying at different times that the most important thing we should have done is decide who we were not going to win. We tried to appease everybody, which is what policy people always try to do because it’s not nice to have people yelling at you. You lose the perception of what’s important, and we never made a decision in the White House to decide that, unlike Reagan, by the way, who made that decision. Unfortunately, it’s gotten beyond his definition. But we needed to make a definition of who we planned to alienate, so that it wouldn’t have bothered us when we did it. We used to have this problem with farmers. We spent an enormous amount of our effort trying to appease farmers whose votes we would never be able to get in the farm bill. We would always justify it by being concerned about farmers and states that in fact we had advantages in, and then we would do things constantly for the farmers at the expense of our position with consumers. You should make policy on that basis, but you always need a factor of where your base is going to be, and where you are going to get support. I don’t see how government can functionally operate or elections can have any meaning when in fact you do not have parties or constituencies that are rewarded or not rewarded by success.

Young

One of the rather striking things about the Carter Presidency is the investment of human and staff resources in the marketing or building of issue coalitions. Wexler’s operation was a major investment of energy that doesn’t quite parallel things you’ve seen in the most previous Presidency. The picture I’m getting is that for reasons independent of receptivity to the country of a policy initiative, policy was decided and legislation was developed, and then after that the coalition building began. Is that a fair model?

Caddell

Yes, basically that’s how things worked.

Young

And what you’re saying is that you made calculations of who your enemies were and what your constituents were.

Caddell